1. Background

Medical tourism is a growing phenomenon with a bright future. Nowadays, countries with tourist attractions are investing in medical tourism, so that attracting foreign tourists has become a growing competition among the organizations involved in the tourism industry (1-5). The globalization of health services has created a new kind of tourism, which is commonly known as health tourism (6). Features, such as the existence of multidisciplinary hospitals, competitive prices, and international quality of global standards, are effective in advancing the globalization of healthcare (7). Advances in medical technology and therapeutic procedures have led to the development of medical tourism during the twentieth century (8). Medical tourism, which is a search for medical services beyond national boundaries is defined as a process, in which medical tourists travel to new places seeking treatment and care (9-14). The payments for these services are usually out of pocket (15).

Medical tourism is not a new phenomenon. In the past, the wealthy patient from developing countries has traveled to developed countries in order to access medical services that were unavailable in their countries. However, today, the reverse trend in medical tourism from the developed world to the developing countries has been created to receive health services, such as cardiac, plastic, and orthopedic surgery and infertility treatments (16-26). The main reasons for medical tourism include the high cost of medical treatment, long waiting lists, lack of qualified doctors, the lack of access to necessary services, and high technology in the country of origin (6, 7, 21, 22, 27-29). Moreover, investing in this sector can increase income, improve services, bring foreign exchange earnings, and promote general tourism (6).

Despite the legal framework for medical tourism development in Iran, this industry is currently facing several challenges. These challenges are lack of specific medical tourism structure at the international, national, and regional levels, the lack of a medical tourism system, definition and formulation of laws, policies, and plans, the lack of infrastructure, and the lack of supervision system. Some other difficulties are weaknesses in the management process and designing benefit packages provided to medical tourists, such as uncertain prices, particularly in the private sector, the lack of insurance coverage, the lack of governmental support for private sector investment, and the lack of a clear marketing system (30, 31).

2. Objectives

This study aimed at comparing the medical tourism industry based on general profile, the competitiveness of tourism and travel, governance and policy, the status of medical tourism, and medical tourism infrastructure in Iran with selected countries.

3. Methods

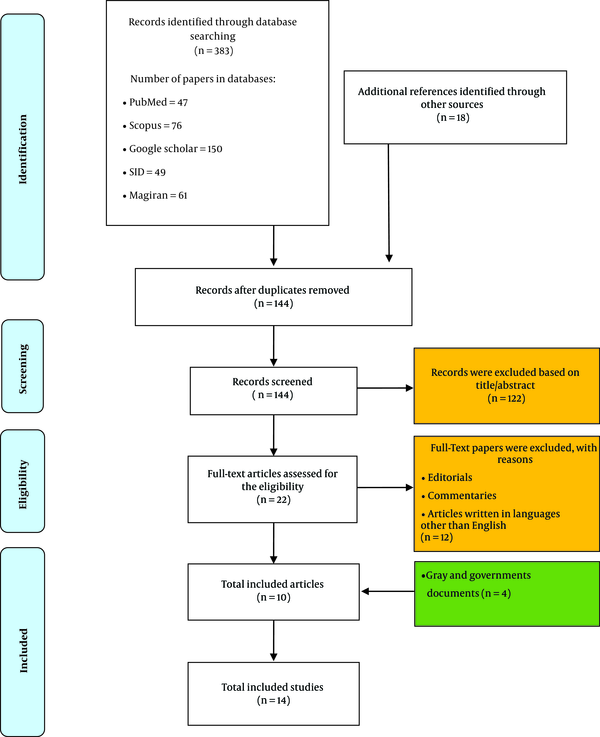

This was a comparative study conducted in 2020. The data collection was conducted by searching valid sources, including PubMed, Web of Knowledge, Scopus, Magiran, SID, Google search engine, and Google Scholar, and also the websites of the World Tourism Association, Ministry of Tourism, and the Ministry of Health of the selected countries. The search was performed using the keywords of medical tourism, health tourism, health travel, and medical travel combined with countries’ names. An example of the search strategy using PubMed is as follows: ("medical tourism"[title/abstract]) or ("health tourism"[title / abstract])) or ("medical travel"[title/abstract])) or (health travel [title/abstract]) and (Singapore [title / abstract]) or (Turkey [title / abstract]) or (Costa Rica [title / abstract]) or (Jordan [title / abstract]) or ("United Arab Emirates" [title / abstract]) or (Iran [title / abstract])

The needed data published from 2000 to 2020 were collected. Inclusion criteria for studies were 1- All articles and reports related to medical tourism in selected countries, 2- articles published between 2000 and 2020, and 3- articles published in English and Persian language. Reports and articles that were inconsistent with the objectives of the study were excluded. The search strategy to obtain studies is summarized in Figure 1.

The inclusion criteria for countries were the development status of countries, developing countries located in the different continent, and being a top destination for medical tourism. Furthermore, Iran's neighboring countries that are Muslim have similarities to Iran (Turkey, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)) and have organized activities in the field of medical tourism and also Singapore ((Asia-Pacific) since it is the world's oldest country in the field of medical tourism) were selected for comparison. Upon reviewing the literature, on the basis of inclusion criteria, six countries were selected purposefully, including Singapore, Turkey, Costa Rica, Jordan, United Arab Emirates, and Iran.

After the literature review, the variables related to the medical tourism industry were identified, and data gathered using a researcher-made checklist. The extracted data were classified according to the analysis components and then were organized as comparative tables. The comparative table was completed for the six selected countries. Comparative tables included components, such as general profile, tourism and travel competitiveness, governance and policy, the status of the medical tourism industry, and medical tourism infrastructure in selected countries. The framework analysis based on the identified components was used to analyze the data.

4. Results

The comparative findings are presented in five sections: general profiles, tourism competitiveness, policy-making and governance of medical tourism, the status of the medical tourism industry, and the medical tourism infrastructure of the selected countries.

4.1. General Profile of the Selected Countries

As shown in Table 1, Turkey, with a population of about 84.33 million, and Costa Rica, with a population of 5.09 million, had the highest and lowest populations, respectively.

| Country | Continent | Population (Million People)(2019) (32) | Currency | Formal Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singapore | Asia | 5.85 | Singapore dollar (SGD) | Language: Chinese, Malay, and English. But the official business language in Singapore is English |

| Turkey | Europe | 84.33 | Lira (TRY) | Turkish |

| Costa Rica | America | 5.09 | Colon (CRC) | Spanish |

| Jordan | Asia | 10.203 | Dinar | Arabic |

| United Arab Emirates | Asia | 9.89 | Dirham | Arabic |

| Iran | Asia | 83.992 | Rial | Persian |

General Profile of the Selected Countries

4.2. The Competitiveness of Tourism and Travel of Selected Countries

As is shown in Table 2, the Singapore (rank 7th) and Turkey (rank 125th), respectively, had the best and worst safety and security among the selected countries. Singapore was ranked third regarding international openness, and Iran was ranked 118. Regarding price competitiveness, Iran was ranked first in the world, and Singapore was ranked 102. Regarding health and hygiene, there was no significant difference between the five countries (Costa Rica, Singapore, Jordan, the UAE, and Turkey), but Iran ranks 89th in health and hygiene and is the last among the selected countries. Iran was ranked 79th in terms of information and communication technology (ICT) readiness, which is much weaker than other countries. Regarding environmental sustainability, Costa Rica was ranked 17th in the world, while Turkey was ranked 126th among the countries with the highest and lowest rank in this index. In terms of tourism service infrastructure, Iran was ranked 108th, and UAE was ranked 22, which are the lowest and highest among the six countries.

| Country | Factor | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety and Security | International Openness | Competitive Price | Prioritizing Travel and Tourism | Health and Hygiene | Human Resources and Labor Market | ICT Readiness | Cultural and Business Resources | Environment Sustainability | Tourism Services Infrastructure | Air Transport Infrastructure | Ground and Port Infrastructure | Business Environment | Natural Resource | Change in Global Rank (From 2017 to 2019) | |

| Singapore | 6 | 3 | 102 | 6 | 60 | 5 | 15 | 38 | 61 | 36 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 120 | From 13th to 17th |

| Turkey | 125 | 52 | 48 | 39 | 65 | 97 | 71 | 17 | 126 | 37 | 20 | 56 | 71 | 77 | From 44th to 43 th |

| Costa Rica | 75 | 20 | 93 | 16 | 86 | 45 | 37 | 72 | 17 | 29 | 63 | 86 | 61 | 8 | From 38th to 41st |

| Jordan | 48 | 68 | 83 | 32 | 67 | 111 | 66 | 101 | 60 | 81 | 70 | 89 | 56 | 119 | From 75th to 84th |

| United Arab Emirates | 7 | 83 | 64 | 71 | 51 | 26 | 4 | 45 | 41 | 22 | 4 | 31 | 9 | 103 | From 29th to 34th |

| Iran | 74 | 118 | 1 | 115 | 89 | 100 | 79 | 33 | 107 | 108 | 88 | 79 | 121 | 99 | From 93rd to 89th |

The Tourism and Travel Competitiveness in Selected Countries (The World Economic Forum Annual Report) (33)

The UAE was ranked 4th regarding air transport infrastructure, and Singapore is ranked second regarding ground and ports infrastructure, while Iran is ranked 88th and 79th in both of these two indicators, respectively. In terms of competitiveness in travel and tourism, the six studied countries are ranked as follows: Singapore, the UAE, Costa Rica, Turkey, Jordan, and Iran, respectively.

4.3. Governance and Policy of Medical Tourism of Selected Countries

Table 3 presents the governance structure, key stakeholders, and main strategies for the medical tourism industry of the selected countries. As shown in Table 4, the main difference between the selected countries and Iran is in the medical tourism industry. In all countries, this industry is under the supervision of the Ministry of Tourism or Ministry of Health, but in Iran, this industry is under the supervision of several ministries. The other similarities observed among the selected countries were the key stakeholders.

| Country | Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance Structure | Main Stockholders | Strategies | |

| Singapore | Ministry of health | Singapore Tourism Board, Infrastructure Development Board, Marketing Companies, Hospitals, Immigration Bureau, Hospitality Department (34). | Improving the quality of health care; being trusted in all respects; international accreditation of hospitals; signing contracts with Central Asian countries in the field of medical tourism; facilitating visa issuance; practical support of the private sector by the government (tax incentives, interest-free loans, etc.) (34). |

| Turkey | Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Turkey | Governorate, Municipality, Chamber of Commerce, travel agencies, private and public hospitals, hotels, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Association of Travel Agents of Turkey (TÜRSAB), the Turkish Tourism Investors Association (TYD), the Association of Turkish Investors and Hotels (TÜROB), the Federation of Turkish Hotels (TUROFED) and the Tourism Guides Association (TUREB) (35). | Tenth Development Plan of Turkey: Developing and strengthening the medical tourism marketing system; attracting two million foreign patients in 2023 and earning $ 20 billion dollars as important goals in the 2013 - 2017 strategic plan; Considering treatment visa for medical tourists; signing a contract with developed countries in the field of medical tourism; Practical support from the private sector by the government (tax incentives, interest-free loans, etc.) (36). |

| Costa Rica | Ministry of Competition | Ministry of Health, hospitals, marketing companies, universities, tourism agencies, international insurance agencies, hotels (37). | Non-visa medical tourists entrance with very few restrictions; Focus on medical tourists from neighboring countries; Practical support of the private sector by the government (tax incentives, interest-free loans, etc.) (37). |

| Jordan | Ministry of Tourism | Ministry of Health, Jordanian Ministry of International Planning and Cooperation, Medical Tourism Board, Jordanian Health Accreditation Council, Jordanian Private Hospitals Association, Hotels, Marketing Companies, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (38). | Developing a marketing strategy and assessing demand for the Jordanian medical tourism market in cooperation with the United States Agency for International Development; National Tourism Strategy with the aim of doubling the medical tourism industry; exchanging medical tourists with developed countries; using private sector in the prosperity of medical tourism (38). |

| United Arab Emirates | Ministry of Health and Prevention | Commercial Tourism and Marketing Bureau, Immigration, Aerospace, Hospitality, Hospitals and Private and Governmental Healthcare Centers, Marketing Companies, Active Tourism Companies, Private Investment | Contract with developed countries in the field of medical tourism; Applying specialist doctors from developed countries; Facilitating the issuance of visas in November 2012 for medical tourists and increasing its duration; Development of the private sector to enter this market; Practical support from the private sector by the government (tax incentives, interest-free loans, etc.)(Dubai Health Strategies 2016-2021) (39). |

| Iran | The organization for Cultural Heritage of Handicrafts and Tourism | Cultural Heritage of Handicrafts and Tourism, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Health and Medical Education | Iran intends to host 20 million foreign tourists and earn 15 billion dollars from this industry by 2025 (20-Year Vision Plan of the Islamic Republic of Iran (Perspective 2025)) (40). |

Governance and Policy of the Medical Tourism Industry of the Selected Countries

| Country | Factor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Tourist Arrival; (Million) World Bank (2018) (41). | Number of Medical Tourist Arrival | Main Customers | Global Rank Regarding the Quality of Health Care Facilities and Services (World Medical Tourism Forum, 2020-20201) (42). | Global Rank Regarding the Medical Tourism Industry; (World Medical Tourism Forum, 2020 - 20201) (42). | |

| Singapore | 14.673 million tourists | Annually about 1,200,000 | China, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Japan, and the United States | 6th | 15th |

| Turkey | 45.76 million tourists | Annually about 700,000 on average | European countries (Germany, Bulgaria, Greece) and Arab countries of the Persian Gulf, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Iran | 32nd | 27th |

| Costa Rica | 3.017million tourists | Annually about 500,000 people | 80% from the US | 20th | 7th |

| Jordan | 4.15million tourists | Annually about 300,000 people | Of the 84 countries, mainly from the Arab region, the United States, Britain, and Canada | 30th | 35th |

| United Arab | Abu Dhabi: 16th | 31th | |||

| Emirates | 21.286 million tourists | An average of 800,000 annually | From most countries, especially developed countries such as Britain, the United States and European countries | Dubai: 10th | 22th |

| Irana | 7.295 million tourists | An average of 200,000 people annually | Azerbaijan, Iraq, the Persian Gulf States | ||

The Status of Medical Tourism of Selected Countries

Pertaining to strategies, Turkey has precisely described the “Tourism Strategy of Turkey - 2023”, which includes the main strategies for the tourism industry, specific objectives, and operational plans required to achieve these strategies. In the UAE, medical tourism strategies have been described in the framework of Dubai Health Strategy 2016 - 2021. In Iran, the strategies of the tourism industry are described in the 20-Year Vision Plan of the Islamic Republic of Iran (Perspective 2025), which indicates how many tourists entered, how many jobs will be generated, and how much investment will be needed. However, there is no specific strategy for medical tourism. Only regarding health tourism, the number of health tourist's arrival up to 2025 is mentioned. One of the main strategies indicated an interaction between developed countries in the field of medical tourism in selected countries other than Iran.

4.4. The Status of Medical Tourism of Selected Countries

As presented in Table 3, Turkey had the highest tourist arrival, while Costa Rica had the lowest arrival. The average cost per tourist (dollar) is different in each country, with Singapore as the most expensive destination (Mean = 1390 $) and Iran as the cheapest one at the rate of 665 $.

Our findings showed that in contrast to Singapore, with the highest average number of medical tourist arrivals (1.200.000 per year), Iran had the lowest average of 200,000 health tourists per year.

The main customers (medical tourists) were different among the selected countries. Therefore, the main customers of the UAE and Jordan are from all over the world, especially the developed countries, such as the United States and Britain. About 80% of the medical tourists in Costa Rica come from the United States, and the main customers of Turkey are from Europe, the Arab countries, and even Iran. Meanwhile, most of Iran’s medical tourists come from neighboring countries (Arab countries of the Persian Gulf, Azerbaijan, and Iraq).

The average annual income of medical tourists among selected countries depends on their arrival. Singapore is ranked first, and Iran is ranked the last with an average annual income of about 600 million US $ (cultural heritage, handicrafts, and tourism organization, 2014).

According to the ranking by the Medical Tourism Association, Singapore ranked first (six in the world) regarding the quality of health care facilities and services, whilst Iran is not ranked among the 41 countries. Considering the medical tourism industry, Costa Rica was ranked 7th, followed by Singapore, the UAE (Dubai), Turkey, UAE (Abu Dhabi), and Jordan, respectively, with the world rank of 15th, 22nd, 27th, 31st, and 35th.

4.5. Medical Tourism Infrastructure of Selected Countries

As depicted in Table 5, Turkey was ranked first among the selected countries with 42 hospitals accredited by joint commission international accreditation standards (JCI (, whereas Iran was ranked last without having a JCI accredited hospital.

| Country | Factor | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Licensed Hospital and Clinic (International Accreditation Organization) | The Percentage of Medical Care Provided to Medical Tourists.; 1. Public Hospital; 2. Private Hospital | Main Competitive Advantages in Medical Tourism | Main Challenge | Therapeutic Brand | Number of Beds (Per 10,000 Population) (44) | 1. Per Capita Physician; 2. Per Capita Nurse (Per 10,000 Population) (44) | |

| Singapore (35, 45). | 21 | 30; 70 | High-Quality Health services (Complicated Surgery), Advanced Medical Infrastructure, and Acceptance of international insurance | The high cost of healthcare and heavy dependence on foreign human resources | Use of stem cells in the treatment of transplant disease | 24 (2015) | 19.5; 28 |

| Turkey (46) | 48 | 10; 90 | Reasonable health care costs, Medical staff fluent in English, 5 star hotels nearby hospitals, and Acceptance of international insurance | Low security in the tourist cities of Turkey in recent years | oncology, cardiology, cardiovascular surgery, orthopedic therapy, traumatology, plastic surgery, test-tube baby (fertility tourism), hemodialysis, oral treatments and dental services | 27 (2013) | 17; 18 |

| Costa Rica (37) | 3 | No specific statistics available | Advanced Private Facility for Health Services, easy access, Healthcare and tourism costs are far lower than in North America, and Acceptance of international insurance | Dental services and oral and dental surgery | 12 (2015) | 11.1; 19 | |

| Jordan (47) | 10 | 40; 60 | Low medical expenses, skilled physicians, and acceptance of international insurance | Stomach surgery, cosmetic surgery, eye exams, heart surgeries and routine checkups | 14 (2015) | 25.6; 40.5 | |

| United Arab Emirates (48) | 38 | No specific statistics available | High quality health care, High physician-to-patient ratio, high security, and Acceptance of international insurance | Heavy dependence on foreign specialist human resources | Cosmetics surgery | 11.5 (2013) | 19.3; 40.9 |

| Iran (49) | 0 | Low medical expenses and skilled physicians | Lack of coordination between the stakeholder organizations, lack of provision of some of the necessary infrastructure (air transportation, visa issuance, etc.) for accepting medical tourists | Liver Transplant; Cardiovascular Surgery | 15 (2014) | 8.9; 14.1 | |

Medical Tourism Infrastructure of the Selected Countries

The participation of the private sector in healthcare delivery is 90% in Turkey, 70% in Singapore, and 60% in Jordan. No information was available for other countries (UAE, Turkey, and Iran).

According to Table 5, reasonable pricing of healthcare services was proposed as a competitive advantage for the medical tourism industry among Turkey, Iran, and Jordan. Insurance coverage in selected countries except Iran was mentioned as an advantage.

The main challenges in the medical tourism industry of the selected countries are listed in Table 5. Therefore, the most important challenges heavily depend on external human resources in the UAE and low level of security in tourism cities of Turkey and management issues, such as lack of coordination between stakeholder organizations in Iran.

Also, Jordan had the highest (25.6) physician per capita index (per 10,000 populations), while Iran had the lowest (8.9). Regarding the nurses per capita, the UAE is attributed to the highest (40.9 nurses per 10,000) and Iran to the lowest.

5. Discussion

One of the growing businesses in the health industry is health tourism (5, 12). Infrastructure and intermediaries play an important role in the development of the medical tourism industry (50). As it is known, the most important prerequisites for the development of medical tourism are basic infrastructure in the tourism sector, accessibility, competitive prices, and political stability. Comparing the mentioned countries in this study, derived the conclusion that countries with more facilities gained a higher ranking in medical tourism (33). These facilities include proper tourism development infrastructure (security, international openness, competitive prices, health and hygiene, human resources and labor market, ICT readiness, cultural and business resources, environment sustainability, infrastructure of tourism services, air transportation infrastructure, ground and port infrastructure, business environment, and natural resources). Many studies in Turkey have identified wide transportation infrastructure, affordable price, and the high number of accredited hospitals as strengths for the industry (51, 52). The international accreditation of medical centers can play an important role in the development of infrastructure, and the advertising and using effective tourism marketing tools can drive more demand.

All of the indicators in tourism and travel competitiveness are low in Iran except pricing, which is ranked as the first cheapest country in the world (33). The growing medical tourism industry requires the optimal provision of all tourism infrastructures and not only the promotion of different indicators.

One of the important factors that highlights Thailand and Singapore as medical tourism destinations is the high quality of care (45, 52). Singapore also has a positive reputation in high-quality medical services and has established itself as a core brand of “medical excellence” in the international arena (12). Based on the report of the Medical Tourism Organization, the UAE, Turkey, and Jordan are the three most important destinations for medical tourism in the Middle East. Some Asian tourism destinations have been successful in attracting tourists because of high-quality medical facilities and trust in the destination brand (53). Focusing on a few areas first and mastering them would be more commercially practical in establishing a position among other countries.

Despite the fact that Iran has good conditions in terms of competitive price, presence of skilled physicians, and low waiting time among the studied countries, but other medical tourism infrastructures are not enough invested. These findings are consistent with the results obtained by Delgoshaei et al. (30, 40, 49). In addition, Hadian et al. reported that necessary technology and technical infrastructure for the development of medical tourism in Iran are not provided. For example, until 2017, Iran has not been able to obtain a JCI license even for one hospital, and the average per capita physician/nurse index is much lower than the global one. In order to promote medical tourism, it is necessary to recognize the strategic medical tourism status of each province in the country, supply a specialized workforce, provide high-quality services, improve infrastructure, and promote a positive attitude of authorities to support the medical tourism industry (54). Factors that can play a positive role in the development of medical tourism in Iran are advanced services for infertility treatment, cosmetic and dental surgery, organ transplantation and cell therapy, cultural similarity and familiarity with neighboring countries, and competitive prices (55-57). Measures, such as improving human resource communication skills and developing private hospitals in accordance with international standards, can also be effective in developing medical tourism.

The main difference between the selected countries and Iran lies down in the organizational structure of the main stakeholders of the tourism industry. Hadian et al. showed that one of the challenges for growing medical tourism in Iran is the presence of different organs of political and decision-making, as well as the cultural and political conditions (58). In all other countries, this industry is organized and supervised by specific coordination bodies. Coordinating policies and strategies between ministries and organizations involved and reviewing some laws can help facilitate cross-sectoral coordination in this area. One of the important factors in the development of the medical tourism industry is the focus on attracting tourists from neighboring countries (59). Generally, certain populations are attracted more to certain locations. This might be due to a similar ethnic and cultural background.

In order to increase Iran’s ability to compete with countries in the region, such as Turkey, in attracting medical tourists, long-term plans should be developed to strengthen the infrastructure and cultural reforms, increase private sector participation and plan for the efficient use of mass media and local press for raising awareness (60). This requires a national effort and redefining the role of health tourism in the economy, as well as a strong trustee to follow up these measures.

The strengths points of this study are the comprehensiveness of the selected countries and obtaining systematic information according to the appropriate strategy search. One of the limitations of the study is that in many items, the existing indicators are not updated, and some of the documents were in languages other than English and Persian.

5.1. Conclusions

Despite the evidence of growing reverse trends of medical tourism by the arrival of medical tourists from developed countries to developing countries, as well as the strategic location of Iran in attracting tourists, establishing infrastructures for attracting foreign revenues is essential for the growth of this industry. Iran should undertake major reforms in the tourism infrastructure, especially the air transportation infrastructure, tourism infrastructure, and international openness, in order to become a leading player in medical tourism. These actions are necessary for Iran in the Middle East to compete with those successful countries, especially the neighboring countries (Turkey, Jordan, and the UAE).