1. Context

Occult hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is characterized by the detection of a low level of HBV DNA in the liver or serum of people who are seronegative for HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) in a period other than the window period of acute infection (1, 2). Occult HBV infection (OBI) has been proposed to occur in several clinical contexts such as the recovery of the past infection characterized by the presence of antibodies to HBsAg (anti-HBs); chronic HBV carriage with very low, undetectable HBsAg levels and the presence of anti-hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) as the only serum marker (isolated anti-HBc) or without any serum marker of HBV (seronegative); and chronic hepatitis B with surface gene escape mutations (3).

Some significant clinical concerns have been suggested for OBI, including (1) The probability of HBV transmission through blood transfusion or organ transplantation (4, 5); (2) chronic liver disease progression toward cirrhosis due to persistent inflammatory necrosis (6); (3) hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development due to the direct oncogenicity effect of HBV and/or the formation of necrotic inflammation following persistent replication of the virus (7); and (4) The possibility of HBV reactivation in immunosuppression conditions such as receiving chemotherapy or other immunotherapy (8).

The prevalence rate of OBI has ranged from zero to 63% among different populations studied in various provinces of Iran. This diversity has been observed among different groups in one region, as well as among a specific group from different areas of the country. For instance, the OBI prevalence in Tehran province in the north of Iran varied from zero among blood donors (BDs) (9) and multi-transfused patients (MTPs) (10) to 18% in HIV-positive individuals (11), 20% in HCV-positive patients (12), and 22% among people who inject drugs (PWID) (13). On the other hand, some studies found no OBI cases among Iranian BDs in provinces such as Tehran (9), Razavi Khorasan (14), Khuzestan (15), Kermanshah (15, 16), and Yazd (17) and some surveys reported the high rates among BDs in Isfahan (11.6%) (18), Fars (15.8%) (19), and Kerman (16.2 %) provinces (20).

This systematic review and meta-analysis study was performed to characterize the OBI epidemiology in Iran and estimate the pooled prevalence among different low- and high-risk Iranian populations such as BDs, hemodialysis (HD) patients, and HIV- and HCV-positive patients. The results of our review would help health authorities to make appropriate decisions for control of OBI in Iran, especially among high-risk groups.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategies

This systematic review and meta-analysis study was conducted following the PRISMA 2009 statement. The main purpose of the investigation was the presence of HBV DNA identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the blood samples of different population groups in Iran. Indexing phrases included “Iran” and all terms that referred to occult HBV infection everywhere in the text (OBI OR “Occult Hepatitis B” OR “Occult HBV” OR “HBsAg negative” OR “HBs Antigen negative”). Language equivalents of these words were used to search the documents published in Persian sources. Some international electronic resources such as ISI, PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Proquest, as well as four Iranian databases including Scientific Information Database (SID), Barakat Knowledge Network System (previously named as IranMedex), Iranian Database of Publication (Magiran), and the Regional Information Centre for Science and Technology (RICeST), were searched until the end of 2018. Furthermore, all references identified from bibliographies of relevant review articles were manually searched. Iranian databases were explored for gray literature such as research projects, dissertations, theses, and abstracts. Besides, some available pertinent abstract booklets and conference proceedings were manually reviewed.

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

After reviewing the titles and abstracts, all records that reported the prevalence of OBI among healthy individuals or different patient groups of Iran were chosen to review their full texts. Variables such as the first author, year of publication, year of study, study location, study population, sampling method, the number of cases with HBsAg and HBV DNA seropositivity, anti-HBc test results, and diagnostic methods used to assess the serum HBV genome were extracted from each study. The main inclusion criteria were the assessment of the HBV genome among at least 30 HBsAg seronegative samples selected through random or non-random sampling methods in a cross-sectional survey. Laboratory methods included Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) or chemiluminescence immunoassay to screen serum HBsAg and PCR techniques to detect serum HBV DNA. Surveys that evaluated HBV DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells or liver tissue samples were excluded. Besides, case reports, review articles, editorials, or letters with no report of OBI prevalence in a specific population were not included. The quality of studies was independently evaluated by two investigators, and eligible studies were selected based on their agreement.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using comprehensive meta-analysis software Ver. 3.3.070 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). Binomial distribution was used to calculate the prevalence in each study. The number of cases with detectable HBV DNA and the total number of studied samples were entered to calculate the event rate and its 95% confidence interval (CI). If a study referred to the event rate but did not provide the number of positive cases, it was recalculated through multiplying the total number of samples by the reported rate of OBI frequency in percentage. A weight was assigned to each study as the inverse variance. Using the Der-Simonian and Laird method, a random-effect model was applied when heterogeneity between studies was identified based on Cochran’s Q-test (P < 0.05) and I-square (I2) statistics (values of > 50%). The point prevalence rates and their 95% CIs for different populations were illustrated by forest plots.

Subgroup analyses were performed to explore the possible factors associated with heterogeneity. A meta-analysis was also implemented after removing surveys with most influences on the heterogeneity due to the reporting of a very high prevalence rate among a specific population. Moreover, additional analysis was done after excluding studies assessing the OBI rate among only cases with anti-HBc seropositivity. Furthermore, a meta-regression analysis was used to investigate significant changes in the prevalence rates over time. All statistical data were considered significant if a P value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

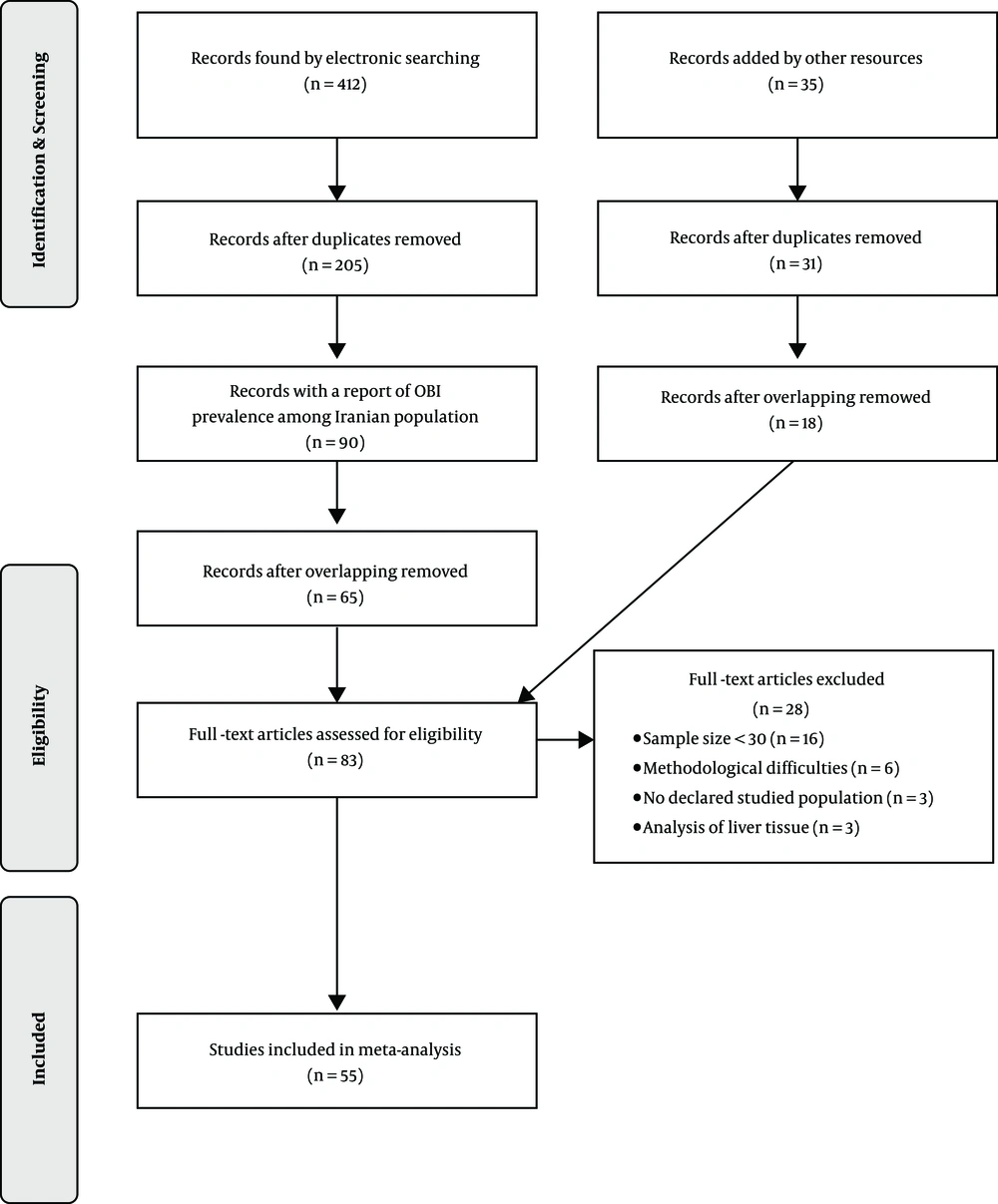

In the initial search of 254 citations retrieved from international electronic sources and 158 citations found in Iranian databases, 205 non-duplicated documents were selected, of which 90 surveys determined the prevalence of OBI in the Iranian population (Figure 1). The search for gray literature added 31 non-duplicate pertinent citations. After removing 38 overlapping surveys (the same studied population, sample sizes, methods, and findings), 83 non-duplicated and non-overlapping surveys were evaluated. A total of 55 non-duplicate and non-overlapping documents met the inclusion criteria and were used in the analysis (Table 1) (9-63). They reported OBI prevalence among 14,485 individuals (min: 31, max: 5000) from 16 provinces of Iran during 2004 - 2018 (Table 1). The studied population included healthy populations such as BDs, tissue donors, and healthcare personnel, as well as high-risk groups including thalassemia, hemophilia, and HD patients, HCV and/or HIV-positive individuals, PWID, patients with unknown liver disease, and family members of HBsAg-positive cases. All studies applied a PCR technique to detect OBI, comprising conventional PCR (20 studies), nested PCR (15 studies), and real-time PCR (20 studies).

| Study | Date (Years) | Province | Population | Sample Size | HBV Serology | HBV DNA Detection Method | OBI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conduction | Publication | |||||||

| Ghaziasadi et al. (21) | Un | 2017 | Markazi | GP (Children) | 558 | HBsAg- | Real-time PCR | 54 (9.68) |

| Azarkar et al. (22) | 2016 - 2018 | 2019 | South Khorasan | GP | 596 | Isolated anti-HBc+ | Nested PCR | 61 (10.23) |

| Karimi et al. (15) | 2013 | 2016 | Kermanshah/Khuzestan | BDs | 2031 | HBsAg- | Real time PCR | 0 (0) |

| Abbasi et al. (16) | 2013 | 2016 | Khuzestan | BDs | 184 | HBsAg- | Nested PCR | 0 (0) |

| Ahmadi Ghezeldasht et al. (14) | 2018 | 2018 | Razavi Khorasan | BDs | 545 | HBsAg- | Real-time PCR | 0 (0) |

| Shahabi et al. (23) | Un | 2009 | Razavi Khorasan | BDs | 60 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Nested PCR | 0 (0) |

| Amini Kafi-abad et al. (9) | Un | 2007 | Tehran | BDs | 230 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Conventional PCR | 0 (0) |

| Vaziri and Javadzadeh Shahshahani (17) | 2015 | 2017 | Yazd | BDs | 74 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Conventional PCR | 0 (0) |

| Alizadeh and Milani (24) | 2008 - 2009 | 2014 | Tehran | BDs | 5000 | HBsAg- | Real-time PCR | 2 (0.04) |

| Khamesipour et al. (25) | Un | 2011 | Guilan | BDs | 78 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Real-time PCR | 1 (1.28) |

| Pourazar et al. (18) | Un | 2005 | Isfahan | BDs | 43 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Conventional PCR | 5 (11.63) |

| Behzad-Behbahani et al. (26) | 2001 - 2002 | 2006 | Fars | BDs | 131 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Conventional PCR | 16 (12.21) |

| Behzad-Behbahani et al. (19) | Un | 2011 | Fars | BDs | 76 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Real-time PCR | 12 (15.79) |

| Kazemi Arababadi et al. (20) | 2008 | 2009 | Kerman | BDs | 352 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Conventional PCR | 57 (16.19) |

| Vaezjalali et al. (27) | 2011 | 2013 | Tehran | BDs | 80 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Nested PCR | 40 (50.00) |

| Samiee et al. (28) | 2014 - 2016 | 2018 | Tehran | Cornea donors | 90 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Real-time PCR | 11 (12.22) |

| Ahmad Akhoundi et al. (29) | 2011 | 2015 | Tehran | HCWs (Dental) | 52 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Real-time PCR | 1 (1.92) |

| Borzooy et al. (30) | Un | 2015 | Tehran | Healthy HCWs | 120 | HBsAg- | Real-time PCR | 4 (3.33) |

| Abbasi et al. (31) | Un | 2012 | Golestan | HD patients | 100 | HBsAg- | Conventional PCR | 0 (0) |

| Joukar et al. (32) | 2009 | 2012 | Guilan | HD patients (59 HCV + cases) | 507 | HBsAg- | Conventional PCR | 0 (0) |

| Kazemi Arababadi et al. (33) | Un | 2009 | Kerman | HD patients (30 HCV + cases) | 90 | HBsAg- | Conventional PCR | 0 (0) |

| Attarpour Yazdi (35) | Un | 2016 | Tehran | HD patients (19 HCV + cases) | 45 | HBsAg- | Conventional PCR | 0 (0) |

| Attarpour Yazdi (34) | Un | 2017 | Yazd | HD HCV + patients | 34 | HBsAg- | Conventional PCR | 0 (0) |

| Ranjbar et al. (63) | 2011 | 2017 | Tehran | HD patients | 200 | HBsAg- | Real time PCR | 1 (0.50) |

| Ramezani et al. (36) | 2013 - 2014 | 2015 | Tehran | HD patients | 100 | HBsAg- | Real time PCR | 1 (1.00) |

| Rastegarvand et al. (37) | 2012 | 2015 | Khuzestan | HD patients | 203 | HBsAg- | Nested PCR | 6 (2.96) |

| Haghazali et al. (38) | 2007 | 2011 | Qazvin | HD patients (10 HCV+ cases) | 129 | HBsAg- | Conventional PCR | 5 (3.88) |

| Keyvani et al. (39) | 2007 | 2013 | 14 provinces | HD patients | 103 | Isolated anti-HBc+ | Conventional PCR | 5 (4.85) |

| Ziyaeyan et al. (40) | Un | 2011 | Fars | HD patients | 55 | HBsAg- | Real time PCR | 4 (7.27) |

| Hashemi et al. (41) | 2011 - 2012 | 2015 | Khuzestan | Relatives of HD patients | 82 | HBsAg- | Nested PCR | 0 (0) |

| HD patients | 82 | HBsAg- | 9 (10.98) | |||||

| Ziaee et al. (42) | Un | 2017 | South Khorasan | Hemophilia | 86 | HBsAg- | Nested PCR | 8 (9.30) |

| Kazemi Arababadi et al. (43) | 2006 - 2007 | 2008 | Kerman | Thalassemia (27 HCV+ cases) | 60 | HBsAg- | Conventional PCR | 0 (0) |

| Makvandi et al. (44) | 2011 - 2012 | 2014 | Khuzestan | Patients with Elevated ALT | 120 | HBsAg- | Nested PCR | 12 (10.00) |

| Kaviani et al. (45) | 1997 - 2001 | 2006 | Fars | Patients with Cryptogenic hepatitis | 104 | HBsAg- | Conventional PCR | 2 (1.92) |

| Hashemi et al. (46) | 2011 - 2012 | 2015 | Khuzestan | Patients with Cryptogenic cirrhosis | 50 | HBsAg- | Nested PCR | 7 (14.00) |

| Sharifi-Mood et al. (47) | 2005 - 2006 | 2009 | Siatan & Baluchestan | Family members of HBsAg + cases | 110 | Isolated anti-HBc+ | Conventional PCR | 3 (2.73) |

| Shahmoradi et al. (48) | Un | 2012 | Mazandaran | Children born to HBsAg + mothers | 75 | HBsAg- | Real-time PCR/Nested PCR | 21 (28.00) |

| Ayatollahi et al. (49) | 2016 | 2019 | Yazd | Patients with cured HBV infection | 96 | HBsAg- | Real-time PCR | 28 (29.17) |

| Shavakhi (50) | 2003 - 2004 | 2004 | Tehran | HCV + patients | 31 | HBsAg- | Conventional PCR | 0 (0) |

| Jonaidi-Jafari et al. (10) | 2009 - 2010 | 2017 | Tehran | HCV + Thalassemia and hemophilia patients | 145 | HBsAg- | Conventional PCR | 0 (4.85) |

| Eshraghi-Mosaabadi et al. (51) | 2013 - 2014 | 2018 | Tehran | HCV + PWID | 94 | HBsAg- | Nested PCR | 7 (7.45) |

| Zandieh et al. (52) | Un | 2005 | Tehran | HCV + patients | 201 | HBsAg- | Nested PCR | 17 (8.46) |

| Shavakhi et al. (53) | 2002 - 2004 | 2009 | Tehran | HCV + patients | 103 | HBsAg- | Nested PCR | 20 (19.42) |

| Vakili Ghartavol et al. (12) | 2010 - 2011 | 2013 | Tehran | HCV + patients | 50 | HBsAg- | Nested PCR | 10 (20.00) |

| Majzoobi et al. (54) | 2013 - 2014 | 2016 | Hamadan | HCV/HIV + patients | 48 | Isolated anti-HBc+ | Conventional PCR | 0 (0) |

| Zhand et al. (55) | Un | 2015 | Golestan | HIV + patients | 120 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Conventional PCR | 0 (0) |

| Aghakhani et al. (56) | 2014 | 2016 | Tehran | HIV + patients (30 HCV + cases) | 92 | HBsAg- | Real-time PCR | 2 (2.17) |

| Tajik et al. (57) | 2015 - 2017 | 2018 | Tehran | HIV + patients | 151 | HBsAg- | Real-time PCR | 4 (2.65) |

| Janbakhsh et al. (58) | Un | 2017 | Kermanshah | HIV + patients (37 HCV + cases) | 66 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Real-time PCR | 8 (12.12) |

| Mohraz et al. (11) | Un | 2016 | Tehran | HIV + patients (99 HCV + cases) | 172 | HBsAg- | Real-time PCR | 31 (18.02) |

| Honarmand et al. (59) | 2012 | 2014 | Fars | HIV + patients | 84 | HBsAg- | Nested PCR | 53 (63.10) |

| Chenari et al. (60) | 2011 - 2013 | 2014 | Razavi Khorasan | HTLV-1 + patients | 109 | HBsAg- | Real-time PCR | 1 (0.92) |

| Asli et al. (13) | 2013 - 2014 | 2016 | Tehran | PWID | 59 | HBsAg-anti-HBc+ | Nested PCR | 13 (22.03) |

| Azizolahi et al. (61) | 2015 | 2017 | Khuzestan | Patients with rheumatologic disorders | 134 | HBsAg- | Real-time PCR | 1 (0.75) |

| Ghorbani Bejandi et al. (62) | Un | 2016 | Tehran | Patients with Behcet's disease | 95 | HBsAg- | - | 7 (7.37) |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; anti-HBc+, Seropositive for anti-hepatitis B core antigen; BDs, blood donors; HBsAg-, seronegative for hepatitis B virus surface antigen; HBsAg +, seropositive for hepatitis B virus surface antigen; HCWs, healthcare workers; HCV+, seropositive for hepatitis C virus; HD, hemodialysis patients; HIV+, seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus; GP, general population; PWID, people who inject drugs; Un: undetermined.

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

The rate of OBI prevalence considerably varied in different parts of the country with the highest prevalence (63.1%) reported among the HIV-positive population in Fars province (Table 1).

3.1. OBI Prevalence Among Blood Donors

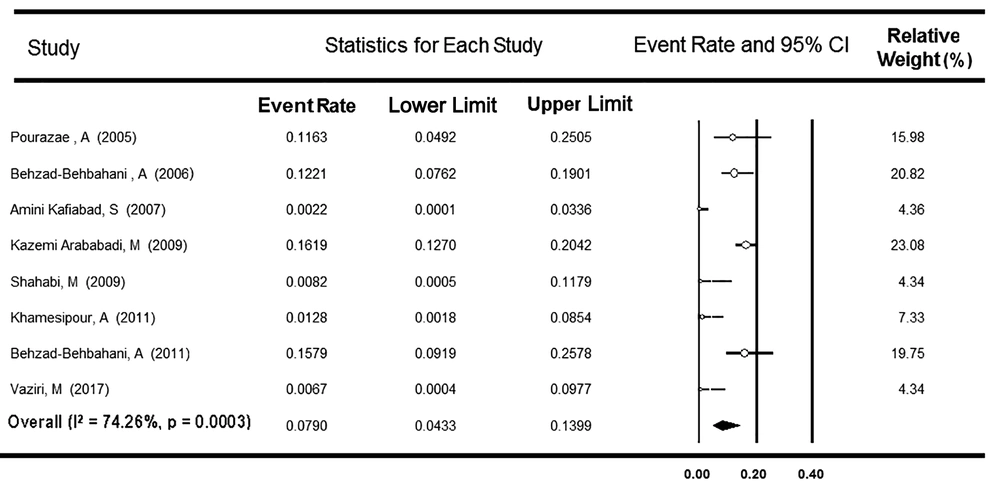

A total of 13 surveys with a report of OBI prevalence among Iranian BDs were used in the meta-analysis. Nine studies investigated the presence of OBI only among HBsAg-negative, and anti-HBc-positive BDs, and four studies explored OBI among HBsAg-negative BDs, regardless of their anti-HBc test results. As Table 2 shows, the first group comprised 1,124 individuals from six provinces. The Cochrane Q-test showed heterogeneity between the studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 90.1%), and the rate of OBI prevalence was estimated at 8.81% (95% CI: 4.11 - 17.91%). After excluding one survey reporting an unexpectedly high rate of OBI (50.0%) (27), the value of I-square decreased to 74.3%, and the OBI rate declined to 7.90% (95% CI: 4.33 - 13.99%, Figure 2). Among the remaining eight surveys, the rate of OBI did not vary by the conventional, real-time, and nested PCR subgroups (P = 0.105, Table 2).

| Population | Prevalence | Sample Size, Total (Min, Max) | Pooled Estimate | Heterogeneity Test | I-Squared, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point, % | 95% CI | Cochran’s Q | P Value | ||||

| Blood donors | With nine surveys included only anti-HBc-positive cases | 1124 (43, 352) | 8.81 | 4.11 - 17.91 | 80.7 | < 0.001 | 90.1 |

| After removing one survey with a report of very high prevalence rate | 1044 (43, 352) | 7.90 | 4.33 - 13.99 | 27.2 | 0.003 | 74.3 | |

| Based on the PCR method used to detect HBV DNA | |||||||

| Conventional (five studies) | 830 (43, 352) | 8.31 | 3.75-17.42 | 16.3 | 0.003 | 75.8 | |

| Real-time (two studies) | 154 (76, 78) | 7.87 | 2.21 - 24.45 | 6.4 | 0.011 | 84.5 | |

| Nested (one study) | 60 (60, 60) | 0.82 | 0.04 - 16.08 | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | |

| Between subgroups | - | - | - | 4.5 | 0.105 | - | |

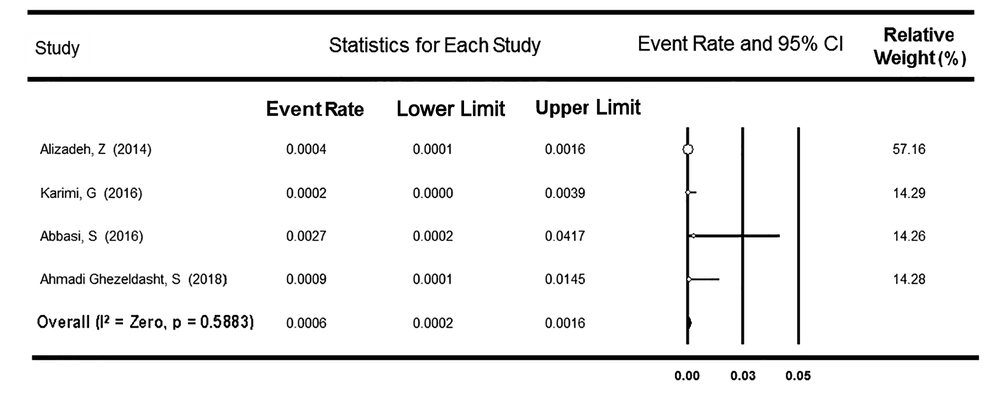

| With four studies investigating HBsAg-negative BDs regardless of their anti-HBc test results | 7760 (184, 5000) | 0.06 | 0.02 - 0.16 | 1.9 | 0.588 | 0 | |

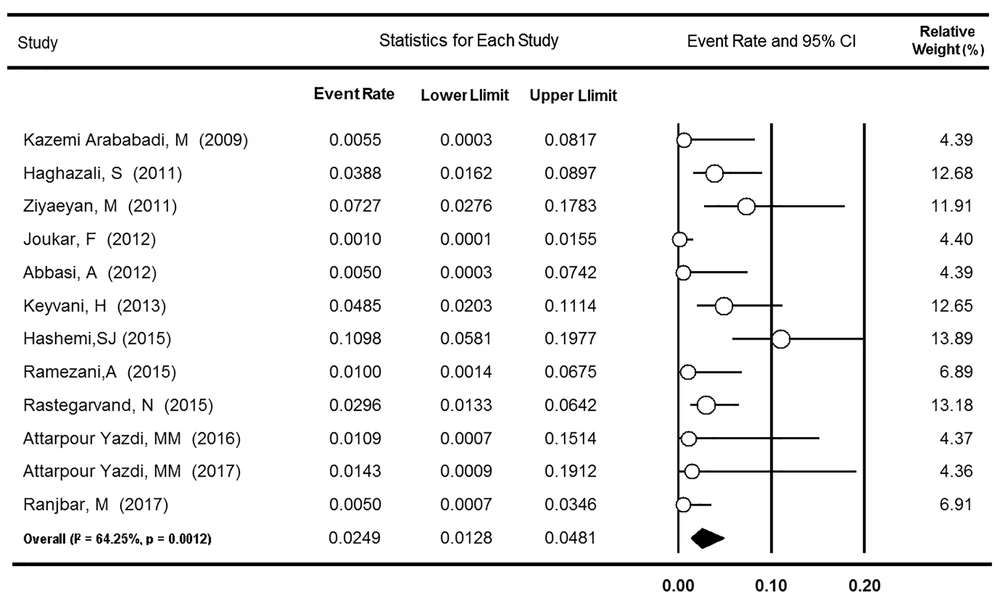

| Hemodialysis patients | With all 12 related studies | 1648 (34, 507) | 2.49 | 1.28 - 4.81 | 30.8 | 0.001 | 64.2 |

| After excluding one survey with only isolated anti-HBc cases | 1545 (34, 507) | 2.12 | 0.98 - 4.54 | 30.6 | 0.001 | 67.3 | |

| Based on the PCR method used to detect HBV DNA | |||||||

| Conventional (six studies) | 905 (34, 507) | 1.01 | 0.28 - 3.53 | 8.9 | 0.113 | 43.9 | |

| Real-time (three studies) | 355 (55, 200) | 1.98 | 0.44 - 8.43 | 7.7 | 0.021 | 74.0 | |

| Nested (two studies) | 285 (82, 203) | 5.58 | 1.29 - 22.75 | 6.6 | 0.010 | 84.8 | |

| Between subgroups | - | - | - | 7.4 | 0.024 | - | |

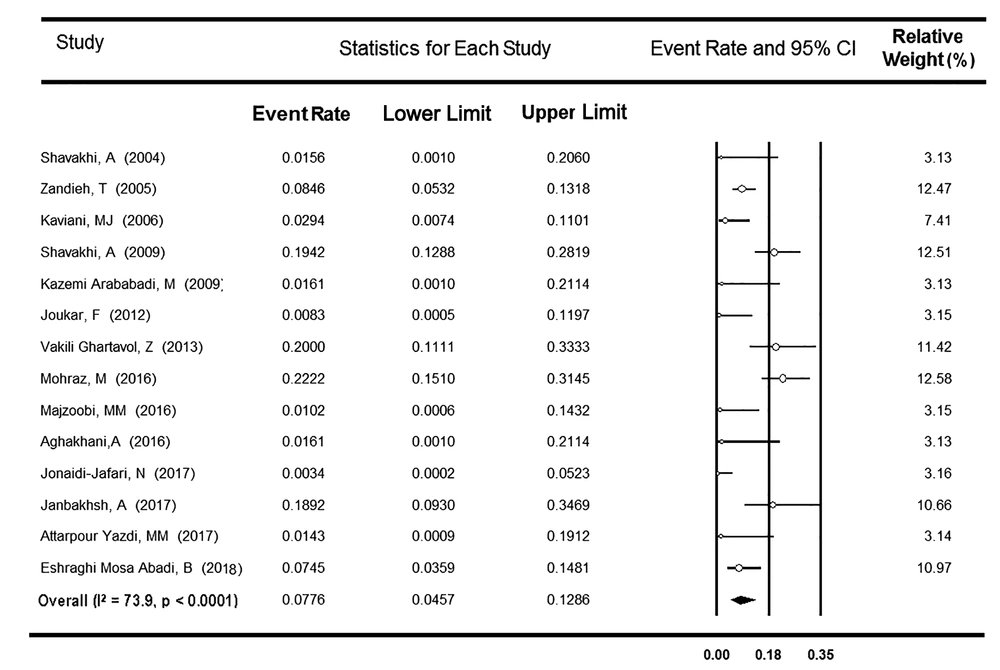

| HCV-positive patients | With all 14 related studies | 1029 (30, 201) | 7.76 | 4.57 - 12.86 | 48.2 | < 0.001 | 73.9 |

| After eliminating two surveys with only anti-HBc positive cases | 944 (30, 201) | 7.32 | 4.10 - 12.75 | 43.6 | < 0.001 | 74.8 | |

| Based on the PCR method used to detect HBV DNA | |||||||

| Conventional (six studies) | 367 (30, 145) | 1.51 | 0.54 - 4.16 | 2.2 | 0.824 | 0 | |

| Real-time (two studies) | 129 (30, 99) | 17.01 | 6.96 - 35.95 | 3.9 | 0.048 | 74.4 | |

| Nested PCR (four studies) | 448 (50, 201) | 12.85 | 7.70 - 20.67 | 11.9 | 0.008 | 74.7 | |

| Between subgroups | - | - | - | 25.9 | < 0.001 | - | |

| With six studies with HCV RNA-positive patients | 561 (30, 201) | 8.77 | 4.01 - 18.11 | 21.4 | 0.001 | 76.8 | |

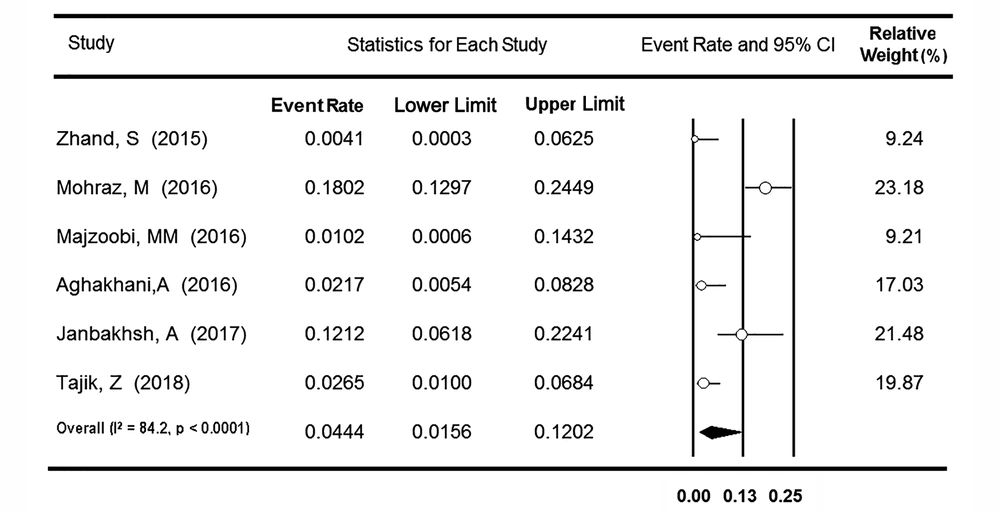

| HIV-positive patients | With all seven related studies | 733 (48, 172) | 6.91 | 1.90 - 22.17 | 116.3 | < 0.001 | 94.8 |

| After removing one survey with a report of very high prevalence rate | 649 (48, 172) | 4.44 | 1.56 - 12.02 | 31.7 | < 0.001 | 84.2 | |

| Based on PCR method used to detect HBV DNA | |||||||

| Conventional (two studies) | 168 (48, 120) | 0.65 | 0.06 - 6.54 | 0.2 | 0.650 | 0 | |

| Real-time (four studies) | 481 (66, 172) | 6.95 | 2.57 - 17.45 | 22.2 | < 0.001 | 86.5 | |

| Between subgroups | - | - | - | 9.3 | 0.002 | - | |

| After removing three surveys with only anti-HBc positive cases | 499 (84, 172) | 11.78 | 2.24 - 43.77 | 94.7 | < 0.001 | 96.8 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Max, maximum; Min, minimum.

The second group included 7,760 donors from four provinces. There was no heterogeneity between the studies (P = 0.588), and the rate of OBI prevalence was assessed as low as 0.06% (95% CI: 0.02 - 0.16%, Figure 3). A meta-regression analysis indicated no significant time trend in the OBI prevalence rate among both subpopulations of BDs (P = 0.967 and P = 0.510, respectively).

3.2. OBI Prevalence Among Hemodialysis Patients

Twelve surveys from eight provinces of Iran reported the rate of OBI among 1,648 HD patients. Based on heterogeneity found between the studies (P = 0.001, I2 = 64.2%), the prevalence rate was estimated to be 2.49% (95% CI: 1.28 - 4.81%, Figure 4). After excluding one survey assessing OBI among only patients with isolated anti-HBc (39), no significant change occurred in the value of I-square (67.3%) and OBI prevalence (2.12%; 95% CI: 0.98 - 4.54%). As Table 2 indicates, the rate of OBI was higher in the nested PCR subgroup (5.58% [95% CI: 1.29 - 22.75%]) than in the real-time and conventional PCR subgroups (1.98% [95% CI: 0.44 - 8.43%] and 1.01% [95% CI: 0.28 - 3.53%], respectively, P = 0.024). In addition, no significant change over the years was found in the OBI prevalence among Iranian HD patients (P = 0.946).

3.3. OBI Prevalence Among HCV-Positive Patients

A total of 14 surveys from six provinces of Iran reported the OBI prevalence among 1,029 anti-HCV-positive patients. Considering heterogeneity found between the studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 73.9%), the rate of OBI prevalence was estimated at 7.76% (95% CI: 4.57 - 12.86%) (Figure 5). Based on the meta-analysis of only six studies that reported occult infection among 561 anti-HCV- and HCV RNA-positive patients, the OBI prevalence was estimated to be 8.77% (95% CI: 4.01 - 18.11%) (Table 2). After excluding two surveys assessing OBI among only anti-HBc-positive patients (54, 58), no change was observed in both I-square (74.8%) and OBI frequency (7.32%; 95% CI: 4.10 - 12.75%). Among the remaining 12 studies, a subgroup analysis was done to assess the modulating effect of three different methods used to detect serum HBV DNA, including conventional, nested, and real-time PCR (Table 2). The rates of OBI were apparently higher in real-time and nested PCR subgroups (17.01% [95% CI: 6.96 - 35.95%] and 12.85% [95% CI: 7.70 - 20.67%], respectively) than in conventional PCR subgroup (1.51% [95% CI: 0.54 - 4.16%], P < 0.001). Besides, no significant relationship was detected between the year of the study and the OBI prevalence rate among Iranian HCV-positive patients (P = 0.058).

3.4. OBI Prevalence Among HIV-Positive People

Regarding the OBI prevalence among the Iranian population with HIV infection, seven surveys reported the rate among 733 HIV-positive cases from five provinces. Based on heterogeneity detected between the studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 94.8%), the OBI frequency was estimated at 6.91% (95% CI: 1.90 - 22.17%). After excluding one survey that reported an unexpectedly high rate of OBI (63.1%) (59), the value of I-square was declined to 84.2%, and the OBI rate decreased to 4.44% (95% CI: 1.56 - 12.02%) (Figure 6). A subgroup analysis was applied to the remaining six surveys regarding the different molecular methods used to diagnose serum HBV DNA (Table 2). The rate of OBI was significantly higher in the real-time PCR subgroup (6.95% [95% CI: 2.57 - 17.45%]) than in the conventional PCR subgroup (0.65% [95% CI: 0.06 - 6.54%], P = 0.002). After removing three studies that evaluated OBI among only the cases with anti-HBc seropositivity (54, 55, 58), the data from the other four surveys were analyzed. With no change in the value of I-square (96.8%), the rate of OBI prevalence increased to 11.78% (95% CI: 2.24 - 43.77%). A meta-regression analysis showed no significant time trend in the OBI prevalence rate among Iranian HIV-positive individuals (P = 0.599).

3.5. OBI Prevalence Among Other Groups

As shown in Table 1, the rate of OBI prevalence has been reported as about 10% in both children and adults from the general Iranian population (21, 22). Likewise, one study among cornea donors in Tehran indicated that 12.2% had molecular evidence of occult infection in their sera (28). The prevalence rate of OBI among PWID ranged from 7.4% to 22% in Tehran (11, 13, 51) while it was as high as 17.9% among this population from Kermanshah (58). Regarding OBI among MTPs, one survey found no cases of OBI among thalassemia patients (43), but another study reported a rate of 9.3% among hemophilia patients (42). Similarly, one survey detected only two cases of OBI among 104 patients with non-cirrhotic cryptogenic hepatitis (45); however, another survey reported a rate of 14% among patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis (46). A considerably high frequency of OBI (28%) was observed among children born to HbsAg-positive mothers (48). In another study, HBV DNA was detected in the serum of 29.2% of individuals with a history of chronic HBV infection who experienced HBsAg seroconversion (49). Moreover, 2-3% of healthcare personnel in Tehran had OBI (29, 30).

4. Discussion

The prevalence of OBI in each population depends partly on the studied people, the prevalence of HBV infection and its risk factors in the community, as well as the sensitivity of techniques used for the detection of serum HBsAg and DNA (64-66). In countries with high endemicity of HBV infection, where the majority of infections occur perinatally or during early childhood, a higher percentage of affected adults might have chronic HBV infection while they are not seroreactive for HBsAg (67). In two systematic reviews of studies conducted in 25 years from 1990 to 2014 (68, 69), the overall rates of HBV infection among the general population of Iran were estimated at 2.2% to 3%, ranging from 0.7% and 0.9% in Kermanshah and Kurdistan provinces, respectively, to 8.9% in Golestan Province. Therefore, Iran could be considered a country with a low-intermediate level of HBV infection. The current systematic review showed a significant variation in the OBI prevalence reported from different provinces of Iran, as well as among diverse populations in the same province. In a study by Azarkar et al. (22), 596 out of 5,234 people selected from the general population of Birjand, South Khorasan, were seroreactive for anti-HBc, of whom 10.2% were detected to be seropositive for HBV DNA. In addition, Ghaziasadi et al. (70) showed that 9.7% of HBsAg- and anti-HBc-negative children in Alborz, Markazi Province, were HBV DNA positive.

Today, OBI is the leading cause of HBV infection following blood transfusion in countries with both low and high levels of HBV endemicity (71). The prevalence of OBI among HbsAg-negative blood donors depends on the level of HBV infection in the community, as well as the serological or molecular methods used to screen the virus (6, 72). The OBI frequency has been reported in 0.1 to 2.4% of HbsAg-negative and anti-HBc-positive blood donor volunteers in western communities with a 5% rate of previous HBV exposure. On the other hand, up to 6% of the donors in HBV-endemic areas, where 70% to 90% of the population show evidence of HBV exposure, are OBI-positive (73). In the present meta-analysis, the prevalence of OBI was estimated at 8.81% (95% CI: 4.11 - 17.91%) among anti-HBc-positive BDs of Iran; however, it was assessed as low as 0.06% (95% CI: 0.02-0.16%) among BDs regardless of their serum anti-HBc status. The detection rate of serum HBV DNA among Iranian HbsAg-negative blood donors varied from 0.15% in Tehran (9) to 2.72% in Zahedan (47). This variation can be partly explained by different prevalence rates of overt HBV infection among BDs from different parts of Iran. In a systematic review of studies with at least 1,000 samples during 2000 - 2015 (74), the overall frequency of HBsAg seropositivity in Iranian blood donors was estimated to be 0.6% (95% CI: 0.4 - 0.8%); however, the prevalence varied from 0.11% in Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari Province to 2.4% in Golestan Province.

Studies showed that occult hepatitis B is mainly found among populations at risk of HBV infection and those with liver disease (2, 6). Similarly, the prevalence of HBsAg seropositivity is reported to be high among high-risk populations of Iran. A review of studies published from 2003 to 2015 (75) estimated the average prevalence rate of 4.8% for HBV infection among drug abusers, PWID, prisoners, and prostitutes in Iran, with the highest prevalence (24.7%) among PWID in Tehran. The HD patients are at risk of acquisition of parenterally transmitted infections. A review of studies published during 1985 - 2015 showed that up to 40% of Iranian HD patients were suffering from HBV infection with an average prevalence of 4% (76). The repetitive blood transfusions, repeated invasive procedures, low response to HBV vaccination, and immunosuppression status are proposed as the reasons for a high incidence of hepatitis B in these patients (77, 78). Moreover, chronic HCV infection in some HD patients may complicate the condition (79). Consistently, the prevalence of OBI has been reported to be up to 36% in HD patients and up to 10% in patients with continuous peritoneal dialysis (6, 77). In 1997, Cabrerizo et al. (80) found HBV DNA in 58% of sera samples and 54% of peripheral blood mononuclear cells derived from 33 HbsAg-negative HD patients. The researchers concluded that the absence of HBsAg in dialysis patients could be due to the presence of HBV surface antigen-antibody immune complex or mutations in the S gene of HBV that precluded HBsAg from being identified by conventional methods. The prevalence of OBI in HD patients varies from country to country in the Middle East. It is reported as 4.1% in Egypt (81). In a study from Turkey (82), OBI was reported in 12 out of 33 HD patients with chronic HCV; however, in other dialysis units from this country, the results were negative (83). Based on the current meta-analysis, the prevalence of OBI among HD patients of Iran was estimated at 2.49% (95% CI: 1.28 - 4.81%) with the highest rate (11%) in patients from Khuzestan Province.

There are significant reports that OBI is more common in people with chronic liver disease, especially those with chronic HCV infection (2, 66, 84). The presence of OBI in patients with chronic hepatitis C has been repeatedly reported and the possible role of OBI in the progression of liver damage following HCV infection has been discussed (78). Cacciola et al. (85) detected the HBV genome in the liver tissue of 33% of patients with HCV infection compared to 14% of HCV-negative groups. In a review, Brechot et al. (64) concluded that HBV DNA was detectable by the PCR technique among 20% - 30% of serum samples of anti-HCV-positive patients and 40% - 50% of liver samples. In the present meta-analysis, the prevalence of OBI among Iranian HCV-positive patients was predicted as 7.76% (95% CI: 4.57 - 12.86%). As hepatitis B and C are common infections with the same transmission routes and risk factors, it is expected that a substantially high prevalence of OBI is reported among patients with chronic hepatitis C (86, 87). Moreover, OBI has shown to worsen the clinical course of HCV infection. Indeed, there is a higher degree of inflammatory activity and fibrosis and a greater rate of cirrhosis and HCC in HCV patients with OBI (88, 89). This clinical consequence of OBI is likely due to the integration of HBV into the host genome or the production of pro-oncogenic proteins by the HBV-free genome within the liver (90). Cacciola et al. (85) reported that 33% of patients with HCV infection and OBI were cirrhotic compared to 19% of those patients with no evidence of occult infection. In addition, it is reported that occult hepatitis B may lead to increased HCV RNA load and serum transaminases levels (90).

Due to similar transmission routes and risk factors, HBV/HIV co-infection is a common condition. Several studies indicated a higher prevalence of HBsAg seropositivity among HIV-positive patients than among HIV-negative individuals (91, 92). The current investigations showed different rates of OBI in HIV-positive groups ranging from zero to 89%; however, the prevalence remains controversial (6, 93, 94). In our systematic review, the prevalence of OBI in HIV-positive patients was estimated to be 6.91% (95% CI: 1.90 - 22.17%); however, a lower rate (4.44%, 95% CI: 1.56 - 12.02%) was discovered after excluding one survey with a high rate of OBI. Some researchers believe that the reasons for diversity observed in OBI prevalence among HIV-positive patients are the same as seen in HIV-negative individuals. These include the different incidence and risk factors of HBV infection in the general population, as well as various methods applied to measure serum HBsAg and/or HBV DNA (6, 94). However, differences between reports may also be explained by fluctuations in HBV proliferation over time, the coincidence of HCV infection, or the impacts of therapeutic strategies for both HIV and HBV. Additionally, heterogeneity between the study populations and regional differences in the overall prevalence of HBV infection may contribute to the observed variance in the prevalence of OBI. HIV patients with OBI might have lower CD4 counts and high plasma HIV RNA loads (93). Reactivation of occult infection and HBsAg seroconversion could also occur with immunosuppression conditions. Thus, the clinical importance of OBI in HIV-positive individuals should be emphasized (90).

5. Limitation

In this review, we tried to address the heterogeneity between studies among different populations through excluding studies with high impacts on the prevalence rates and performing subgroup analysis, as well as meta-regression methods. However, other sources of heterogeneity were impossible to discover.

6. Conclusions

This review estimated the high rates of OBI frequency among high-risk populations of Iran. It is strongly suggested that occult hepatitis B be investigated among Iranian populations with a high chance of its occurrences such as dialysis patients, HCV-positive patients, and HIV-infected individuals.