1. Context

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) is a major public health problem. It is associated with morbidity and mortality and imposes a substantial burden on the worldwide healthcare system (1, 2). About 399,000 people die each year due to hepatitis C, mostly from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. A previous study estimated 71 million people (1% of the world’s population) living with HCV infection in 2015 (3).

Based on the available data, most countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) have a low-to-moderate anti-HCV prevalence (4). A prison is a high-risk place for prisoners who are engaged in risky behaviors such as injecting drugs, tattooing, unwanted sexual intercourse, and sharing syringes. The HCV prevalence is generally higher among prisoners than in the general population, mainly due to risky behaviors of prisoners (5-7). Prisoners are susceptible to various infectious diseases and may spread them after they return to society (8). Information about the HCV prevalence in prisoners can lead to appropriate decisions in public health policy and management.

The previous meta-analysis of HCV prevalence among Iranian prisoners was done by Behzadifar et al. (9) in 2018. Two other studies did not use two rounds of a national study (bio-behavioral and observational studies of HBV and HCV in Iran prisons) conducted in 2015 and 2016 (10, 11) and not reported the prevalence of HCV by province.

2. Objectives

This systematic review and meta-analysis study was done to estimate the pooled HCV prevalence using a new statistical approach (multilevel meta-analysis) in prisoners.

3. Evidence Acquisition

3.1. Search Strategy

All studies used ELISA tests for assessing HCV antibodies. The literature on the HCV-Ab prevalence in Iran was acquired through searching international databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Elsevier, Google Scholar, and Web of Science and Iranian databases, including Scientific Information Database (SID), IranDoc, Health.barakatkns, MagIran, and Civilica. Our last search was conducted on February 8, 2020. To search and include related studies as many as possible, we used the terms “Hepatitis C”, “HCV”, “Prevalence”, “Epidemiology”, “Prison”, “Prisoner”, “Inmates”, “Jails”, and “Iran” (or the names of its provinces) as keywords in titles and/or abstracts in the MeSH word search database.

3.2. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction

Published studies were regarded as qualified for the analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) cross-sectional studies with the full text of the paper available in the Persian or English languages, (2) studies with a sample size of more than 30, and (3) studies reporting the prevalence of HCV antibodies by the ELISA test in Iran provinces. Conversely, the following studies were excluded: (1) non-English or non-Persian full-text reports, (2) studies not providing enough data to estimate the prevalence rate, (3) studies designed as letters to the editor, expert opinions, editorials, commentaries, case-reports, case-series, and reviews, and (4) Studies reporting overlapping data.

3.3. Data Extraction

All articles categorized as potentially relevant were reviewed separately by both of the authors (Mohsen Rowzati and Alireza Najimi-Varzaneh). They evaluated the relevance of each report and summarized the following data using Excel datasheets: First author’s name, year of publication, year of study, number of HCV patients, study sample size, name of the province, and mean age of responders. The analysis was conducted according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) (12). In this study, “The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS)” was used to assess the quality of the included studies. For better data extraction, we used blinding and task separation (13).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

In the current meta-analysis study, two approaches were applied for data analysis. First, we used the “metafor” package in R, version 3.6, software. In this technique, the heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using the Q test (P < 0.10) and I-squared statistics (I2 > 40%). According to the results of the heterogeneity test, we used fixed or random-effect models to determine the prevalence of HCV. According to the central limit theorem, to estimate the pooled effect (θ) in the fixed-effects model, the prevalence of hepatitis C in each study (

4. Results

4.1. Search Results and Study Selection

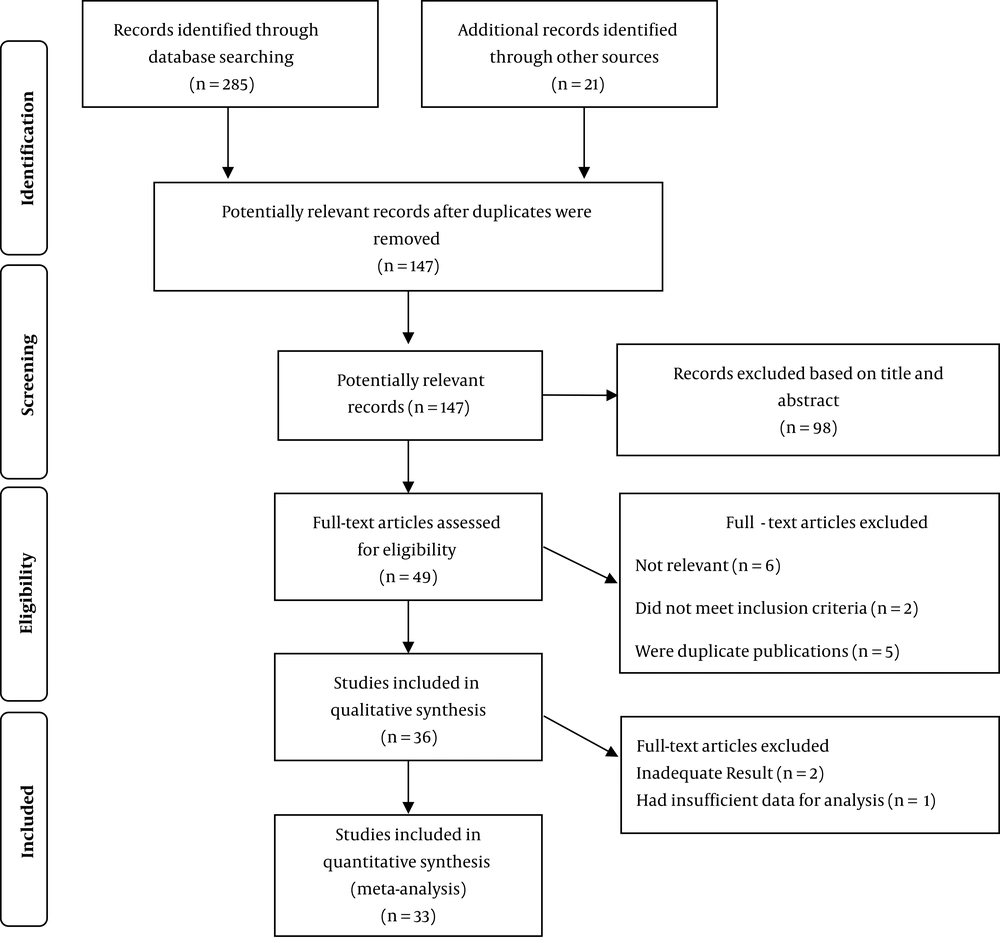

The study selection process is depicted in Figure 1. A total of 147 studies were potentially associated with the prevalence of HCV in Iran provinces. After reviewing the abstracts and titles, 98 studies were eliminated based on the stated inclusion and exclusion criteria. After the full-text screening and quality assessment, a total of 33 records were deemed as eligible studies published until 2019.

4.2. Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus in Iranian Prisoners

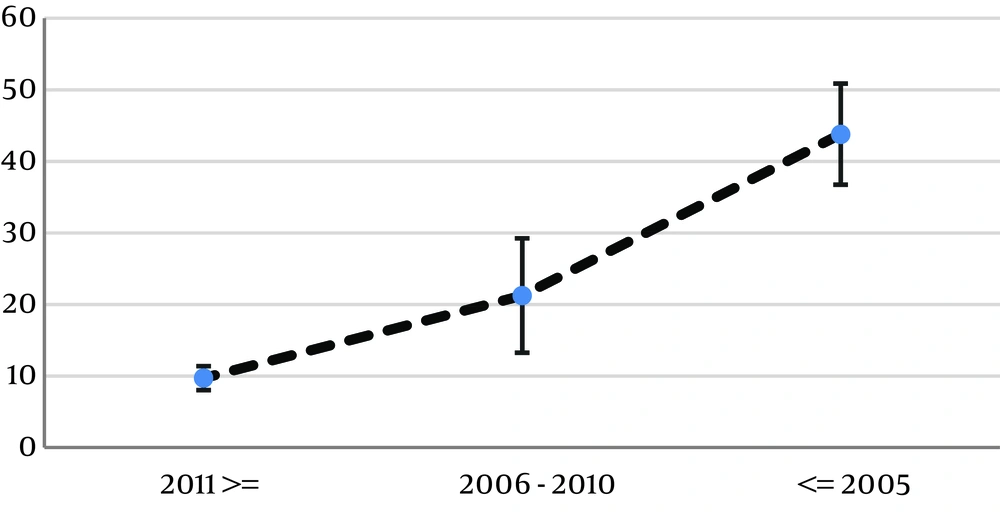

Table 1 presents the study characteristics, including the reference, province, first author’s name, year of publication, year of study, mean age, number of HCV patients, and study sample size. Table 2 represents the pooled prevalence of hepatitis C according to the prevalence in each province of Iran, as well as the pooled prevalence obtained by the multilevel meta-analysis. As can be seen, the pooled prevalence of HCV in prisoners was 24.88% with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) of 19.12% - 31.69%. The results also showed a decreasing trend in the HCV prevalence between 1995 and 2018.

| Province | First Author | Ref. | Year of Publication | Year of Study | Mean Age | Number of HCV Cases | Study Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alborz | Moradi | (10) | 2018 | 2015 | 39.49 | 145 | 1282 |

| Sharafi | (15) | 2019 | 2017 - 2018 | 36.5 | 106 | 1788 | |

| Azerbaijan, East | Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2003 | NA | 74 | 472 |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2002 | NA | 104 | 517 | |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2001 | NA | 118 | 579 | |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2000 | NA | 115 | 480 | |

| Moradi | (10) | 2018 | 2015 | 39.49 | 11 | 297 | |

| Naghili | (17) | 2012 | 2007 | 31.3 | 55 | 192 | |

| Bushehr | Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2002 | NA | 166 | 403 |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2001 | NA | 147 | 355 | |

| Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari | Tajbakhsh | (18) | 2008 | NA | 25.8 | 76 | 600 |

| Moradi | (11) | 2019 | 2016 | 36.29 | 14 | 201 | |

| Fars | Alasvand | (19) | 2015 | 2012 | 37 | 41 | 300 |

| Moradi | (10) | 2018 | 2015 | 39.49 | 58 | 771 | |

| Qazvin | Moradi | (11) | 2019 | 2016 | 36.29 | 60 | 518 |

| Guilan | Mohtasham Amiri | (20) | 2007 | 2003 | 34.7 | 209 | 460 |

| Moradi | (11) | 2019 | 2016 | 36.29 | 105 | 1010 | |

| Golestan | Khodabakhshi | (21) | 2007 | 2002 - 2003 | NA | 28 | 121 |

| Hamadan | Alizadeh | (22) | 2005 | 2002 | 37.9 | 128 | 427 |

| Moradi | (10) | 2018 | 2015 | 39.49 | 74 | 538 | |

| Hormozgan | Davoodian | (23) | 2009 | 2002 | 35.4 | 163 | 249 |

| Moradi | (11) | 2019 | 2016 | 36.29 | 50 | 540 | |

| Isfahan | Alasvand | (19) | 2015 | 2012 | 37 | 101 | 300 |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2004 | NA | 51 | 98 | |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2003 | NA | 144 | 250 | |

| Ataei | (24) | 2011 | NA | 32 | 644 | 1485 | |

| Kassaian | (25) | 2012 | 2009 | 32.6 | 392 | 943 | |

| Nokhodian | (26) | 2012 | 2008 - 2009 | 16.59 | 7 | 160 | |

| Nokhodian | (27) | 2012 | 2009 | 34.54 | 12 | 163 | |

| Isfahan, Lorestan, and Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari | Javadi | (28) | 2006 | 2003 | 513 | 1431 | |

| Kerman | Alasvand | (19) | 2015 | 2012 | 37 | 10 | 312 |

| Moradi | (10) | 2018 | 2015 | 39.49 | 34 | 455 | |

| Kermanshah | Alasvand | (19) | 2015 | 2012 | 37 | 53 | 400 |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2001 | NA | 353 | 1052 | |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2004 | NA | 349 | 896 | |

| Khademi | (29) | 2019 | 2017 | 35.52 | 230 | 1034 | |

| Moradi | (11) | 2019 | 2016 | 36.29 | 76 | 576 | |

| Khorasan, North | Moradi | (11) | 2019 | 2016 | 36.29 | 14 | 280 |

| Khorasan, Razavi | Alasvand | (19) | 2015 | 2012 | 37 | 43 | 400 |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2005 | NA | 19 | 45 | |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2004 | NA | 5 | 66 | |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2002 | NA | 71 | 106 | |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2003 | NA | 76 | 112 | |

| Ghorbani | (30) | 2008 | 2004 - 2006 | NA | 30 | 139 | |

| Khajedaluee | (31) | 2016 | 2008 | 34.42 | 272 | 1114 | |

| Moradi | (10) | 2018 | 2015 | 39.49 | 90 | 1033 | |

| Rowhani-Rahbar | (32) | 2004 | 2001 | 32.8 | 60 | 101 | |

| Khorasan, South | Azarkar | (33) | 2010 | 2008 | 34.7 | 29 | 358 |

| Azarkar | (34) | 2007 | NA | 34.1 | 31 | 400 | |

| Ghafari | (35) | 2019 | 2016 | 37.4 | 24 | 300 | |

| Ziaee | (36) | 2014 | 2009 - 2010 | 34.7 | 68 | 881 | |

| Khuzestan | Moradi | (11) | 2019 | 2016 | 36.29 | 108 | 956 |

| Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad | Moradi | (11) | 2019 | 2016 | 36.29 | 5 | 171 |

| Sarkari | (37) | 2012 | 2009 - 2010 | NA | 72 | 616 | |

| Kurdistan | Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2003 | NA | 105 | 400 |

| Lorestan | Moradi | (10) | 2018 | 2015 | 39.49 | 43 | 378 |

| Markazi | Sofian | (38) | 2012 | 2009 | 30.7 | 91 | 153 |

| Mazandaran | Moradi | (10) | 2018 | 2015 | 39.49 | 26 | 398 |

| Zakizadeh | (39) | 2006 | 2001 | 39.4 | 96 | 312 | |

| Sistan and Baluchestan | Moradi | (10) | 2018 | 2015 | 39.49 | 41 | 356 |

| Salehi | (40) | 2001 | NA | NA | 40 | 441 | |

| Tehran | Alasvand | (19) | 2015 | 2012 | 37 | 25 | 408 |

| Mir-Nasseri | (41) | 2011 | 2001 - 2002 | 35.85 | 311 | 386 | |

| Mir-Nasseri | (42) | 2005 | 2001 | 36.58 | 271 | 346 | |

| Mir-Nasseri | (43) | 2008 | 2001 | 36 | 301 | 386 | |

| Moradi | (11) | 2019 | 2016 | 36.29 | 84 | 1940 | |

| Zali | (44) | 2001 | 1995 | 34.2 | 182 | 402 | |

| Yazd | Moradi | (11) | 2019 | 2016 | 36.29 | 15 | 296 |

| Zanjan | Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2001 | NA | 195 | 360 |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2004 | NA | 276 | 468 | |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2002 | NA | 288 | 480 | |

| Asgari | (16) | 2008 | 2003 | NA | 324 | 523 | |

| Khani | (45) | 2003 | 2001 | 33.7 | 165 | 346 |

| Province | Number of Studies | Prevalence (95 CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Alborz | 2 | 8.58 (3.32 - 13.85) |

| Azerbaijan, East | 6 | 18.56 (10.75 - 26.38) |

| Bushehr | 2 | 41.29 (37.78 - 44.79) |

| Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari | 3 | 18.10 (5.99 - 30.20) |

| Fars | 2 | 10.34 (4.34 - 16.35) |

| Guilan | 2 | 21.29 (19.22 - 23.47) |

| Golestan | 1 | 23.14 (15.62 - 30.65) |

| Hamadan | 2 | 21.78 (5.88 - 37.67) |

| Hormozgan | 2 | 14.32 (11.95 - 16.96) |

| Isfahan | 8 | 34.30 (21.06 - 47.54) |

| Kerman | 2 | 5.27 (1.09 - 9.45) |

| Kermanshah | 5 | 24.23 (14.42 - 34.05) |

| Khorasan, North | 1 | 5.00 (2.44 - 7.55) |

| Khorasan, Razavi | 9 | 33.66 (22.73 - 44.60) |

| Khorasan, South | 4 | 7.83 (6.64 - 9.03) |

| Khuzestan | 1 | 11.30 (9.30 - 13.30) |

| Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad | 2 | 9.78 (7.79 - 12.07) |

| Kurdistan | 1 | 26.25 (21.94 - 30.56) |

| Lorestan | 2 | 26.84 (24.16 - 29.66) |

| Markazi | 1 | 59.47 (51.70 - 67.25) |

| Mazandaran | 2 | 17.18 (14.47 - 20.16) |

| Qazvin | 1 | 11.58 (8.82 - 14.33) |

| Sistan and Baluchestan | 2 | 10.09 (7.72 - 12.45) |

| Tehran | 6 | 48.72 (19.37 - 78.08) |

| Yazd | 1 | 5.06 (2.57 - 7.56) |

| Zanjan | 5 | 56.73 (51.96 - 61.50) |

| Multilevel Pooled Effect | 24.88 (19.12 - 31.69) |

5. Discussion

The findings of this study showed that the estimated prevalence of HCV among Iranian prisoners was 24.88% (number of studies = 33). This rate is lower than the rate reported in Behzadifar et al. study (9) (number of studies = 17, reported HCV prevalence = 28%). Such a difference can be attributed to the number of studies used in the meta-analysis and the use of a powerful statistical approach. In the multilevel meta-analysis, the heterogeneity of each province can be corrected from the overall pooled effect, and the estimation of the pooled effect is reported with higher accuracy (14). Previously published meta-analysis studies have reported the HCV prevalence in different subsets of the Iranian population. This rate is higher than the prevalence in the general population (reported HCV prevalence = 0.6%) (46) and lower than the rate among people who inject drugs (reported HCV prevalence = 52.2%) (1). In comparison with the international studies, this rate is higher than the prevalence reported among prisoners in Egypt (23.6%), Pakistan (15.6%), Libya (23.7%) (47), Italy (22.4%) (48) Brazil (2.4%) (49), France (4.8%) (50), the United States (18%) (51), and Hungary (4.9%) (52) and lower than the rate in California (34.3%) (8), Indonesia (34.1%) (53), Lebanon (28.1%) (47), and Irish prisoners (37%) (54).

Differences in the prevalence of HCV in different studies are due to differences in the type of prisons and prisoners. Most prisoners are at risk of hepatitis due to high-risk behaviors such as injecting drugs, addiction, sexual misconduct, and violence (19). On the other hand, prisoners are not isolated from society; many prisoners are kept for a short period, and many of them return to the community and contact with the general public. This makes hepatitis C prisoners a risk group for HCV transmission to the community. Therefore, paying attention to the prevalence of hepatitis C among prisoners can guarantee community health (19).

Our results also showed a decreasing trend in the HCV prevalence between 1995 and 2018 (Figure 2). Such a reduction can be the result of implementing educational programs and effective therapeutic strategies targeting hepatitis C by the Ministry of Health.

Some limitations exist in the present study, the first of which is not mentioning the type of prisoners in the published articles, and the second is the lack of data and studies from some provinces.

Two strong points of this study are the use of two rounds of a national study conducted in 2015 and 2016 (10, 11) and the use of a new statistical approach (multilevel meta-analysis) for calculating the pooled effect.

6. Conclusions

According to this study, hepatitis C has a high prevalence among prisoners in Iran. Consequently, we recommend the regular screening of prisoners, separating the affected prisoners from the rest, taking remedial measures including easy access to disposable syringes and needles, health education (personal and community), and treatment of addicted prisoners.