1. Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease around the world (1). The prevalence of NAFLD has increased in the past two decades, and the Middle East and South American countries account for the highest prevalence of NAFLD (2). NAFLD is also the second leading cause of liver transplant and the third leading cause of hepatocellular carcinoma (3, 4). The potential of NAFLD to progress to advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma makes it a formidable disease with high morbidity and mortality. Moreover, NAFLD is highly associated with some metabolic comorbidities, including type II diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and metabolic syndrome (5, 6). Therefore, some effective treatment methods are needed to treat patients in the early stages of the disease and prevent its progression into end-stage liver disease.

Currently, there is no standard pharmacological drug for the treatment of NAFLD. Management of some metabolic comorbidities, including obesity, type II diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia, is the main goal of NAFLD treatment (7). Some agents, which are used for the treatment of NAFLD, include insulin-sensitizing agents (pioglitazone), hypolipidemic agents (gemfibrozil), and antioxidants (vitamin E) (8). However, these agents are not broadly recommended due to their adverse effects and unapproved effectiveness in NAFLD (9, 10). Furthermore, promising results have been reported in NAFLD treatment by using pentoxifylline and obeticholic acid. However, the safety and side effects of these agents are not well-established (11-13). Consequently, it seems necessary to find effective agents with minimum side effects.

Beta vulgaris is an herbal agent used as an anti-fever medication in ancient Roma (14). It has been shown that Beta vulgaris reduces blood sugar and induces glucose storage as glycogen in the liver (15). Experimental studies on rats revealed that Beta vulgaris reduces the level of liver enzymes, including aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (16). Nevertheless, there have been some controversies about the effects of Beta vulgaris on liver enzymes in previous clinical trials. In order to obtain consistent results regarding the effectiveness of Beta vulgaris in NAFLD, further studies are needed.

2. Objectives

Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the efficacy of Beta vulgaris extract in the treatment of NAFLD.

3. Methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) (code: IR.TUMS.PSRC.REC.1396.4044). It was also registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (code: IRCT20121017011145N20). The identity and information of the participants remained confidential. Moreover, informed consent was obtained from eligible volunteers prior to participation in the study. All of the participants could withdraw from the study at any time.

3.1. Study Sample

This double-blind, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial was conducted from November 2018 to April 2019 at Shahid Beheshti Hospital of Kashan, Iran. This hospital is a referral teaching hospital, affiliated to Kashan University of Medical Sciences (KUMS).

3.2. Patients and Methods

This study was conducted among patients with NAFLD who were referred from specialized outpatient clinics of KUMS. The participants were selected by purposive sampling based on eligibility criteria. The inclusion criteria for patients were age between 18 and 70 years and a primary diagnosis of NAFLD. The diagnostic criteria for NAFLD included ultrasound evidence of fatty liver (grade II or above) and increased level of liver enzymes (two or three times higher than normal). Ultrasonography was performed by an expert radiologist, and the diagnosis was established by a gastroenterologist. The grade of fatty liver was determined according to the Rumack ultrasound criteria, and the liver biochemical profile was measured based on standard protocols (14).

On the other hand, patients with liver diseases, including Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis, alcoholic fatty liver disease, autoimmune liver disease, or cirrhosis, were excluded from the study. Also, pregnant and lactating women were excluded. Finally, eligible participants were divided equally into case and control groups via simple randomization. For the randomization, the groups were named as Beta vulgaris group and placebo group. Then, the sequence of groups was drawn up by coin tossing. The Beta vulgaris group received vitamin E pearl (300 IU/twice daily), Livergol tablet (140 mg/daily), and Beta vulgaris capsule (400 mg/daily) for six months. On the other hand, the placebo group received the same dosages of vitamin E pearl and Livergol tablet, besides placebo capsules instead of Beta vulgaris capsules for the same amount of time. Also, the participants were asked to do not use Beta vulgaris or its products during the study. The probable intervention complications were followed up closely via telephone contacts. In the first two weeks, three participants of the Beta vulgaris group had mild gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea and nausea. Also, one participant of the placebo group had moderate diarrhea in the first week of intervention, who was excluded from the study.

The demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the participants, including gender, age, weight, height, family history of NAFLD, and history of diet and exercise, were determined at baseline. In addition, the levels of AST, ALT, ALP, prothrombin time (PT), triglyceride (TG), cholesterol (CHL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), fasting blood sugar (FBS), and albumin (ALB), as well as the grade of fatty liver, were measured at baseline and three and six months after the intervention.

3.3. Preparation of Beta vulgaris Extract

About 70 kg of Beta vulgaris root (common beet) was purchased and confirmed by a botanist. Next, the roots were cleaned and extracted according to the maceration technique using 70% ethanol by a specialist in the Medicinal Plants Laboratory of Tehran Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran, Iran. The extracted liquid was concentrated by a rotary evaporator and dried by a spray dryer. Subsequently, 400 mg of the dried extract of Beta vulgaris root was added to a capsule with the same color and size as the placebo capsule. In addition, microbial experiments were carried out on Beta vulgaris extracts to find any possible contamination with pathogens, such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Bacillus cereus.

3.4. Data Analysis

Chi-square test was used to evaluate qualitative variables. Independent samples t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were also used to determine differences between the mean values of the groups. The therapeutic effects of Beta vulgaris were evaluated using repeated measures analysis. Before analysis, the model pre-assumptions, including normality and sphericity, were examined using histograms, box plots, and Mauchly’s tests. All the statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS version 23, and the level of significance was set at 0.05.

4. Results

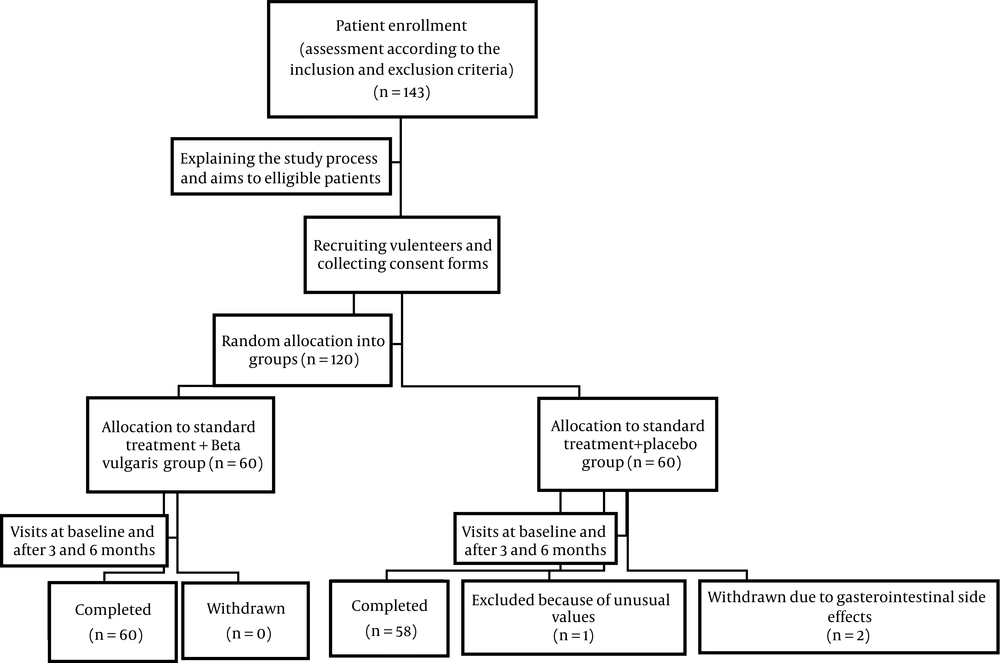

Among the 143 patients who met the study criteria, 120 patients agreed to participate in the study (83.9% response rate). However, two patients from the placebo group left the study due to gastrointestinal side effects (e.g., vomiting and diarrhea). In addition, one patient from the placebo group was excluded from the analysis due to unusual values. The study flowchart is presented in Figure 1. Overall, 62 (52%) patients were male, and 55 (48%) patients were female. The mean (SD) age of the participants was 46.9 (9.7) years, ranging from 18 to 69 years. Other sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

| Variables | Study Groups | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta vulgaris Group (N = 60) | Placebo Group (N = 57) | ||

| Age | 47.5 ± 10.5 | 46.4 ± 8.7 | 0.55 |

| BMI | 30.4 ± 4.4 | 29.3 ± 4.4 | 0.18 |

| Sex | 0.65 | ||

| Male | 33 (53.2) | 29 (46.7) | |

| Female | 27 (49.0) | 28 (50.9) | |

| Family history of NAFLD | 0.63 | ||

| No | 29 (50.8) | 28 (49.1) | |

| Yes | 29 (50) | 29 (50) | |

| Cirrhosis | 2 (100) | 0(0) | |

| Diet status | < 0.01b | ||

| Change from meat to vegetarian diet | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Change from vegetarian to meat diet | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| On a diet in the last six months | 10 (29.4) | 24 (70.5) | |

| Losing weight in the last six months | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| None | 47 (59.4) | 32 (40.5) | |

| Exercise status | 0.71 | ||

| Using bodybuilding devices | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Walking for 15 to 30 min every day in a week | 9 (47.3) | 10 (52.6) | |

| Walking for 15 to 30 min every other day in a week | 29 (60.4) | 19 (39.5) | |

| Walking for 15 to 30 min once a week | 11 (42.3) | 15 (57.6) | |

| Walking for 15 to 30 min once in two weeks | 6 (46.1) | 7 (53.8) | |

| Walking for 15 to 30 min once a month | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Without exercise | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.5) | |

| BMI | 0.19 | ||

| Normal (18.5 - 24.9) | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | |

| Overweight (25 - 29.9) | 26 (47.3) | 29 (52.7) | |

| Obesity (≥ 30) | 30 (60.0) | 20 (40.0) | |

| Stage of NALD | 0.03b | ||

| Grade 1 | 13 (48.1) | 14 (51.9) | |

| Grade 1.5 | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | |

| Grade 2 | 20 (43.5) | 26 (56.5) | |

| Grade 2.5 | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Grade 3 | 14 (77.8) | 4 (22.2) | |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

bP < 0.05.

The mean levels of AST, as one of the main biomarkers of NAFLD, were 51.0 ± 20.9 and 55.5 ± 16.9 mg/dL in the Beta vulgaris and placebo groups, respectively. Also, the mean level of ALT was 61.7 ± 26.2 and 56.7 ± 12.9 mg/dL in the Beta vulgaris and placebo groups, respectively. There was no significant difference in the mean level of biomarkers between the groups at the beginning of the study. Other biochemical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 2.

| Variables | Study Groups | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta vulgaris Group (N = 60) | Placebo Group (N = 57) | ||

| AST | 51.0 ± 20.9 | 55.5 ± 16.9 | 0.21 |

| ALT | 61.7 ± 26.2 | 56.7 ± 12.9 | 0.19 |

| ALP | 199.9 ± 58.3 | 217.5 ± 43.9 | 0.06 |

| FBS | 92.4 ± 6.5 | 92.3 ± 8.3 | 0.06 |

| PT | 12.2 ± 0.69 | 12.0 ± 0.65 | 0.18 |

| TG | 191.0 ± 50.2 | 178.5 ± 23.9 | 0.09 |

| CHL | 192.7 ± 29.7 | 200.6 ± 22.2 | 0.11 |

| LDL | 115.1 ± 27.5 | 119.7 ± 21.7 | 0.31 |

| HDL | 40.9 ± 10.8 | 38.9 ± 4.9 | 0.20 |

| ALB | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 0.88 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

bP < 0.05.

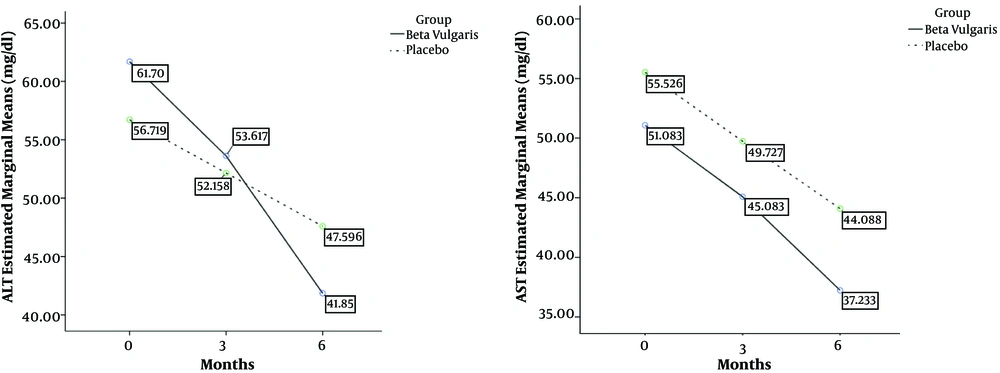

After 60 days of the intervention, the results of intra-group comparisons based on the repeated measures analysis indicated that the AST level decreased significantly over time (F = 74.8, P < 0.001). Also, intra-group comparisons based on repeated measures analysis showed that ALT significantly decreased during and at the end of the study (F = 83.58, P < 0.001). In other words, treatments were effective in both Beta vulgaris and placebo groups. In addition, the inter-group analysis revealed a significant reduction in the AST level in the Beta vulgaris group, compared to the placebo group (F = 4.08, P = 0.04). Contrary to AST, inter-group analysis of ALT showed no significant reduction over time (F = 4.67, P = 0.94). However, the inter-group analysis indicated a significant reduction in ALP (F = 6.47, P = 0.01), FBS (F = 4.13, P = 0.04), and LDL (F = 6.43, P = 0.01) and a significant increase in HDL (F = 5.27, P = 0.02) over six months. Other changes in biomarkers over time are shown in detail in Table 3.

| Variable | Study Groups | Between-Group Comparisons | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta vulgaris Group (N = 60) | Placebo Group (N = 57) | ||||||

| 0th | 3th | 6th | 0th | 3th | 6th | P Value | |

| AST | 51.0 ± 20.9 | 45.0 ± 16.0 | 37.2 ± 11.7 | 55.5 ± 16.9 | 49.7 ± 14.0 | 44.0 ± 11.4 | 0.04b |

| ALT | 61.7 ± 26.2 | 53.6 ± 21.9 | 41.8 ± 15.0 | 56.7 ± 12.9 | 52.1 ± 13.5 | 47.5 ± 15.0 | 0.94 |

| ALP | 199.9 ± 58.3 | 198.1 ± 42.3 | 208.3 ± 38.4 | 217.5 ± 43.9 | 218.7 ± 36.9 | 225.3 ± 36.7 | 0.01b |

| FBS | 92.4 ± 6.5 | 90.2 ± 4.6 | 87.0 ± 5.2 | 92.3 ± 8.3 | 92.0 ± 5.6 | 91.1 ± 5.7 | 0.04b |

| PT | 12.2 ± 0.69 | 12.0 ± 0.4 | 12.0 ± 0.7 | 12.0 ± 0.65 | 12.0 ± 0.5 | 12.2 ± 0.6 | 0. 74 |

| TG | 191.0 ± 50.2 | 174.2 ± 38.2 | 159.5 ± 25.7 | 178.5 ± 23.9 | 173.4 ± 19.3 | 167.6 ± 16.0 | 0.71 |

| CHL | 192.7 ± 29.7 | 182.7 ± 27.2 | 174.4 ± 20.8 | 200.6 ± 22.2 | 190.5 ± 18.4 | 181.1 ± 17.9 | 0.05 |

| LDL | 115.1 ± 27.5 | 106.6 ± 21.7 | 95.9 ± 17.3 | 119.7 ± 21.7 | 114.8 ± 15.5 | 108.0 ± 14.3 | 0.01b |

| HDL | 40.9 ± 10.8 | 45.8 ± 10.0 | 52.5 ± 11.3 | 38.9 ± 4.9 | 41.6 ± 5.6 | 48.4 ± 7.3 | 0.02b |

| ALB | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 0.55 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

bSignificant difference at 0.05.

Analysis of the interaction between time and groups showed a significant interaction regarding ALT (F = 11.84, P < 0.001). In other words, the effect of Beta vulgaris on ALT increased over time. However, there was no interaction between time and groups regarding AST. In other words, the effect of Beta vulgaris did not change over time. The trends of AST and ALT changes over time are presented in Figure 2.

5. Discussion

The present study showed that the use of Beta vulgaris, alongside the standard treatment of NAFLD, could have positive effects on the biochemical markers of patients with NAFLD. Integration of Beta vulgaris in the treatment regimen of NAFLD patients significantly decreased AST and ALP as the main biomarkers of hepatic disease, compared to the standard treatment. Since elevated AST is associated with higher grades of fibrosis among NAFLD patients (17), improvement of AST is a promising way to prevent the progression of liver fibrosis. Although Beta vulgaris extract could not have significant effects on ALT in this study, the interaction between time and groups revealed that the effect of Beta vulgaris on ALT increased over time. It is recommended that future studies evaluate the effect of Beta vulgaris on ALT for more than six months.

Furthermore, Beta vulgaris extract had significant positive effects on other biomarkers, including FBS, LDL, and HDL. Since the treatment of comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, and hyperlipidemia, is one of the goals of NAFLD treatment, Beta vulgaris extract can improve the efficacy of other agents prescribed for NAFLD. To gain a clinical insight into the effect of Beta vulgaris, Cohen’s d index was calculated using the Klauer’s approach (0.3 for AST and 0.6 for ALT). According to the Cohen’s table, the effect size of Beta vulgaris was small for AST and medium for ALT. Therefore, despite the significant P value of AST, its effect size was small, while despite the non-significant P value of ALT, it was more significantly affected from a clinical point of view.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the second study evaluating the efficacy of Beta vulgaris extract in NAFLD patients. In the first study by Srivastava et al. (18), it was found that Beta vulgaris extract had no significant effects on the liver enzymes of NAFLD patients during 12 weeks. As shown in our study, the effect of Beta vulgaris on liver enzymes, especially ALT, increased over time. Therefore, the shorter duration of the study by Srivastava et al. compared to our study may be the cause of the discrepancy between the results. Also, considering the unclear dosage of Beta vulgaris supplement in the study by Srivastava et al. (18), insufficient dosage may be responsible for this discrepancy. Nevertheless, the lipid profile of patients in the Beta vulgaris group significantly decreased, compared to the placebo group. These results are consistent with our findings regarding the effect of Beta vulgaris extract on the lipid profile of patients with NAFLD.

In another study evaluating the hepatoprotective effects of Beta vulgaris on liver damage in male Sprague-Dawley rats, it was found that Beta vulgaris juice exerted hepatoprotective effects on liver damage in a dose-dependent manner (19). This finding supports our hypothesis about the discrepancy between our results and the study by Srivastava and colleagues. Moreover, Ozsoy-Sacan et al. (20) in their study, which assessed the effect of Beta vulgaris extract on the liver of diabetic rats, found that AST, ALT, ALP, total lipid profile, and blood glucose level decreased significantly in the intervention group, compared to the placebo group. Additionally, the anti-hyperglycemic and anti-lipidemic activities of Beta vulgaris have been confirmed in different studies (21-23). Therefore, the positive effects of Beta vulgaris extract on the glycemic status and lipid profile of patients with NAFLD can help physicians manage other comorbidities of NAFLD and improve the outcomes of treatment.

As a result, the integration of Beta vulgaris in the treatment regimen of NAFLD patients has positive effects on liver enzymes and other biochemical markers associated with NAFLD. Since Beta vulgaris is a highly available and low-cost medicinal plant, utilization of Beta vulgaris alongside other treatments of NAFLD can be considered as a new treatment with satisfactory clinical results. However, further studies are needed to evaluate the exact effects and possible side effects of Beta vulgaris on NAFLD.

Despite our findings, this study had two limitations. First, the FibroScan, as one the best noninvasive tests to quantify liver fibrosis, has not been used in this study due to economic considerations. Second, this study was performed for six months due to time limitations. According to our findings, it is recommended that future studies try to find the effect of Beta vulgaris consumption on NAFLD for more than six months.

5.1. Conclusions

The addition of Beta vulgaris extract to the standard treatment of NAFLD could significantly decrease the levels of AST and ALP. Although Beta vulgaris extract could not improve ALT, the interaction between time and groups showed that the effect of Beta vulgaris on ALT increased over time. Also, this study showed that the integration of Beta vulgaris extract, due to its positive effects on FBS, LDL, and HDL, could help physicians manage other metabolic comorbidities of NAFLS. It is recommended that future studies evaluate the possible side effects of Beta vulgaris. In addition, longer studies are needed in order to assess ALT changes over time.