1. Background

Organ donation and transplantation are critical health policy issues in all nations. However, availability of organs is limited, and this shortage is an essential subject (1-3). In Iran with Islam as its the dominant religion, the organ donation law was first passed in 2000 by the Islamic Parliament of Iran. From 2001 to 2010, reports from Iran showed a notably increased rate of transplantation from brain-dead individuals (4). More than 25000 patients were in the waiting list, while the total number of potential donors was about 2500 - 4000 in Iran. However, the mean family consent rate for organ donation was 70 percent in the whole country (5).

Various factors affect the organ donation consent rate after brain death (2, 6). Previous findings show the key role of healthcare professionals in decisions of brain-dead patients’ families for organ donation (7-9). It is believed that healthcare providers’ inappropriate behaviors and their negligence during the patient’s hospitalization have increased unwillingness to consent for organ donation (9, 10). Also, lack of awareness among the general public and medical professionals, socio-cultural and religious factors, legal and ethical aspects, deficiency in family support, and insufficient information about organ donation are principal factors in refusing donation (8, 11). Moreover, media, as the primary source of information regarding organ donation, is an effective factor (12-14).

Organ donation refusal affects the mortality rate of patients waiting for organ transplantation. Transplant coordinators working directly with brain-dead patients’ families are viewed as essential links in the organ donation chain.

2. Objectives

Therefore, we decided to explore transplant coordinators’ views and experiences regarding obstacles to organ donation. Finding problems in the organ donation process is essential to develop clinical and administrative interventions. Hence, an interventional strategy could increase organ donation consent rates. Based on the study’s objectives, the following questions were raised:

What is organ donation?

What are obstacles against organ donation?

What are challenges of persuading brain-dead families to donate organs?

3. Methods

3.1. Study Participants and Sampling Method

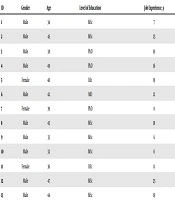

This study was conducted using qualitative content analysis from November 2018 to March 2019. Caution was exercised to include individuals with adequate knowledge and experience regarding the organ donation process at local and national levels. Thirteen experts were selected using the purposive sampling method. This method is typically used in qualitative research to identify and select information-rich cases for the most proper utilization of available resources. This involves individuals who are expert and well-informed in the phenomenon under study (15). A female researcher with a master’s degree interviewed the coordinators. She conducted the interview with the concurrence of other project implementers. She had almost nine years of experience in research on health and its challenges and also experience in conducting qualitative studies. As the interviewer was a healthcare worker, all the participants eagerly participated in the study. The participants had an age range between 32 - 49 years, and their job experience ranged between 6 - 25 years (Table 1).

| ID | Gender | Age | Level of Education | Job Experience, y |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 34 | MSc | 7 |

| 2 | Male | 43 | MSc | 23 |

| 3 | Male | 38 | PhD | 10 |

| 4 | Male | 49 | PhD | 16 |

| 5 | Female | 40 | BSc | 19 |

| 6 | Male | 42 | MD | 12 |

| 7 | Female | 39 | PhD | 8 |

| 8 | Male | 45 | MSc | 18 |

| 9 | Male | 33 | MSc | 6 |

| 10 | Male | 32 | MSc | 6 |

| 11 | Female | 36 | BSc | 11 |

| 12 | Male | 47 | MSc | 25 |

| 13 | Male | 44 | MSc | 19 |

Abbreviations: BSc, bachelor of science; MSc, master of science; MD, medicinae doctor; PhD, philosophiae doctor.

3.2. Qualitative Data Collection

In-depth semi-structured face-to-face interviews with transplant coordinators were applied. The interviews were conducted in one of the hospital’s rooms where the participants worked. The interviews were conducted via telephone for participants who were unavailable (five coordinators) after sending them the guide to the questions via e-mail. The interviews were audio taped for later transcription and translation. The research questions were asked in an open-ended format in a private room where only the participants and the researcher were present. The off-time was chosen for the interview to minimize bias. Each interview lasted on average 50 minutes, and one repeated interview was carried out. During the interview, each participant answered demographic questions of age, gender, education, and work experience.

The participants were asked the following questions:

Could you elaborate on your experience in the process of donating organs for transplant?

What do you expect with your practice in this process?

3.3. Ethical Considerations

Prior to each interview, the participants were informed about the study’s purpose. The interviews were recorded after taking verbal consent. The participants were assured of confidentiality of the data and the right to withdraw at any time. The Ethics Committee of the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences approved the study (code: IR.SUMS.REC. 1396.S16).

3.4. Data Analysis

The interviews were transcribed and analyzed using content analysis. In fact, conceptual ordering was carried out open coding. Two researchers shared in vivo and sometimes in-vitro coding from the transcripts. They continually shared the interview process, extracted codes for better understanding, and clarified future directions. Then, the research team refined the codes to ensure their consistency. At last, the participants checked the correctness of the findings and made necessary changes.

3.5. Rigor

The researchers considered confidentiality, consultation, and interview techniques during the interview. Data collection continued until data saturation. Theoretical saturation was also obtained when the collected data provided no more categories (16). The researchers also considered creditability, dependency, conformability, and transferability to guarantee the trustworthiness of the data. The creditability of data collection was obtained using a semi-structured interview, field remarks, and extended engagement in the subject matter. The dependency criterion was evaluated by peer review and member check strategies. A comprehensive description of the subject, participants, data collection, and analysis was also considered to ensure the transferability of the data (17).

4. Results

Based on the collected data, two main categories formed obstacles to obtaining informed consent, namely external determinants and internal determinants. Each category was further divided into some subcategories. The external determinants category had four subcategories, and the internal determinants category had three subcategories. For some reasons, all the interviews revealed the difficulty of obtaining informed consent from brain-dead patients’ families.

4.1. External Determinants

The environment plays a key role in discouraging families from consenting to organ donation. This issue could be caused by circumstances mentioned below:

4.1.1. Healthcare Providers’ Lack of Empathy

Many of the participants stated that inappropriate behaviors of healthcare providers and negligence during the patient’s hospitalization were obstacles to obtaining informed consent.

“Sometimes, a patient is mistreated in the emergency room, and after brain death the patient’s family say ‘what’s going on?’ When our patient was in the emergency room, you mistreated us; You did not understand, neglected our patient, and didn’t check up on him. Now that this has happened, you are all suddenly interested in talking to us?”

Healthcare providers’ lack of empathy and being inconsiderate to the patient before brain death have major impacts on decision making.

“Here, the doctor doesn’t speak much before surgery. We have patients from abroad who say that you do everything for us, but we would have loved and appreciated it if somebody talked to us! Nobody explains the situation and tells us what is going on”.

The poor communication of the treatment team, especially physicians, with brain-dead patients’ families is considered a form of neglect. It has been the reason for many complaints from these families.

“There have been complaints about the doctors; they say if the doctors were more involved and created better relationship with the families, everything would be resolved much better. We’ve had cases in whom everything was going well, but the doctor didn’t fully report the patient’s physical condition to his family and the relationship between the physician and the family became problematic”.

4.1.2. Inadequate Consultation from Doctors Outside the Hospital

One of the main issues in consenting to organ donation is misdiagnosis and poor consultation provided by doctors in private clinics. Families consult with other doctors to make sure that the diagnosis is correct. Physicians in private clinics provide false information based only on radiological images, without any clinical examination. This false hope prevents organ donation.

“The family members took their patient’s computed tomography scan to a doctor in a private clinic outside the hospital for a second opinion. They said that our son had a car accident and had been declared brain-dead. The doctor looked at the computed tomography scan and gave some feedback that made things difficult for us. They said ‘do not to rush into anything, wait and see what happens’, while the diagnosis of brain death is on clinical observation and you need to examine the patient. Or they might even say that this is not brain death” (transplant unit, processing unit manager, 23 years of experience).

4.1.3. Media Content

The media plays a significant role in providing information on brain death, organ donation, and effect of healthcare providers. Since media programs do not reflect a true image of the treatment staff, they can cause public distrust. Therefore, social media can have negative impact on consenting to organ donation.

“In March 2014, an …. actress was declared brain-dead. We had 12 other brain death cases during the same month, 11 of whom consented to organ donation. All of them told that our loved ones had told us that ‘If I am brain-dead, I want my organs to be donated; just like her’. For the new-year 2016, they made a sitcom about doctors which showed that a doctor had left forceps in the patient’s body. However, we should pay attention to how we are creating laughter. Exactly at the same time, we had 13 brain death cases, out of whom we could only get one consent for donation. It was the same hospital and the same team with more experience, but people were questioning everything and at the same time we expect the families to give their consent”.

4.1.4. Uninformed Comments from Relatives

Most of the time, the influence of others can delay or even stop family members from giving consent. They make doubt about brain death and avoid consenting to organ donation by mentioning cases who gained consciousness.

“The families are in a state of uncertainty and doubt, waiting for someone to give them some hope. For example, a friend comes and says ‘I have a cousin who was in a coma for 2 months. They said he was brain-dead’. Don’t do it. Don’t agree to this!” (49 years old, 16 years of experience).

Occasionally, comments from others can change families’ decisions about organ donation, even after giving consent.

“There have been times where the family says ‘oh! you are from the transplant team,’ and people have told them about us. (environmental factors that are out of our control). For example, the person says that he is ok with this and is willing to do it, but at the end, he does not accept. Then, they sign the agreement, and the patient goes into the operating room; everybody can say something to the family that causes them to refrain from their consent. Therefore, we have to maintain a connection with the family throughout the whole process” (34 years old, 7 years of experience).

4.2. Internal Determinants

Internal factors depend on individuals themselves. In other words, internal factors are the result of one’s thoughts and beliefs.

4.2.1. Hope for Recovery

In many cases, the possibility of miraculous healing results in refusal for organ donation. The transplant administrator at the hospital stated, “some family members say, ‘I’ll go to Imam Reza’s shrine, I’ll go to Shah Cheragh shrine and I’ll ask them to heal my baby’. They say that ‘we won’t consent. We are sure he will heal and if God is willing, my son will recover”.

4.2.2. Denial

The first step for organ donation is the acceptance of brain death by patients’ family members.

“The family members do not accept that their patient is brain-dead. There was a father who said, ‘My son had dinner with me just last night, and in the hospital he moved his arms and legs. I’m sure he’s not brain-dead’ ”.

The parents’ mental state and their emotional dependence are issues that have further fueled unwillingness to organ donation and hindered the process of obtaining consent. Among family members, obtaining the mother’s consent is the most difficult task due to their considerable emotional attachment.

“Our problem is with the mother’s consent. Mothers are the pinnacles of emotion. She thinks her child is going to be cut into pieces. She thinks she will feel guilty afterwards” (49 years old, 16 years of experience).

4.2.3. Disagreement Between Family Members

Differences of opinion and disagreement between family members about organ donation is another obstacle. Hence, obtaining informed consent can be more difficult in such circumstances.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to explore obstacles to organ donation in brain-dead patients’ families from transplant coordinators’ perspective. The findings revealed to two types of external or environmental complications and internal or individual obstacles.

5.1. External Determinants

The present study’s results showed that healthcare providers’ lack of empathy to brain-dead patients’ families was an obstacle to organ donation. These findings are in line with previous studies, indicating that the doctor’s compassion, empathy, understanding of families’ emotions, and commitment to answering families’ questions were quite helpful in the organ donation process (18). Also, neglecting patients can cause difficulties in obtaining consent from families. Other studies also support our findings and prove that the caring relationship of healthcare team with brain-dead patients’ families is highly essential in facilitating decision making and consenting to organ donation (7-9, 19). Therefore, poor communication between the healthcare team, especially doctors, and brain-dead patients’ families has been the subject of complaints. Most of the participants regarded “inappropriate consultation from doctors outside the hospital” as an obstacle, resulting in misdiagnosis and creation of false hope.

A probable reason for this misjudgment is doctors’ lack of awareness or insufficient information about brain death. A study conducted on doctors in Pakistan showed that 54% of them did not have a clear vision about brain death, which made most of them reluctant to disconnect the brain-dead patient from the ventilator (20).

The present study’s findings highlighted the significant role of media content on the family’s decision-making process. Previous findings also confirmed this fact and showed that dependence on the produced content could be either positive or negative. However, some studies (21) indicated that printed media such as newspapers had a significant negative impact. According to these studies, damaging stories were mostly printed in newspapers, especially on cover pages (21).

The influence of others can delay or even stop the process of obtaining consent. The qualitative study by Yousefi et al. (22) is also consistent with this conclusion. They showed that even after consenting to organ donation, conversations between the family and those around could make them hesitant and struggle with the decision-making process (22).

5.2. Internal Determinants

The findings also showed that internal obstacles related to families could stop them from consenting to organ donation. Religious beliefs and hope for miraculous healing are obstacles to organ donation, as well. A study in India also revealed that certain religious beliefs prevented individuals from donating organs (11), although religious leaders in Islam have issued fatwas, permitting organ donation and considering it charitable (23, 24). Other studies have highlighted the positive and negative impacts of religious beliefs and law on organ donation (2, 25). Mojtabaee et al. (23) in their study showed that religious beliefs were among the reasons for families’ refusal to organ donation, which was more common in Sunni families.

Denial of brain death by the patient’s family was an obstacle to organ donation in our study. Studies have shown that although brain death is accepted as a form of definitive death in developed countries, the concept has remained vague in Asian countries (26). A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies revealed that individuals who did not accept a sudden death of a loved one and still hoped for their recovery were reluctant to consent to organ donation. However, families who were aware of their patients’ critical conditions and had the chance to review the autopsy report were more cooperative and understanding (25).

Difference of opinion about organ donation among family members was another obstacle. The current study’s findings showed that it was essential for all family members to agree with the decision; otherwise, consenting to organ donation was less likely (25).

One of the limitations of this study was implementing some interviews via telephone, which could lead to loss of some of the interviewee’s emphasis, due to lack of face-to-face interactions. Moreover, as this qualitative study encompassed only one social context, the results cannot be generalized to other communities.

5.3. Conclusions

Families’ emotional reaction to giving consent to organ donation is inevitable. It is suggested to develop a training course for the treatment team to make them more supportive of patients and their families. The quality of nursing care of brain-dead patients should be supervised. Moreover, families must be given the chance to accept and cope with their loved one’s death. Physicians could not diagnose brain death only through radiology imaging techniques in private clinics. The media should inform the public about the concept of brain death and organ donation. The media should also build trust between people and healthcare providers by creating a positive mindset about organ donation. Furthermore, encouraging people to sign organ donation pledge cards reduces challenges associated with obtaining organ donation consent.