1. Background

Different etiologies of chronic liver injury, such as viral hepatitis (hepatitis C and hepatitis B), alcoholic or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and cholestatic liver diseases, can cause liver fibrosis, which results from the chronic development of liver scar tissue (1, 2). Liver fibrosis represents the early stage of liver cirrhosis, which may progress to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (3). Upon liver injury, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are activated and differentiate to myofibroblasts, secreting a large amount of extracellular matrix (ECM) (4, 5).

Cellular senescence is a stable state of cell cycle arrest and can play an important role in tissue repair, tumor suppression, embryonic development, and protection against tissue fibrosis (6, 7). The secretion of extracellular matrix components, such as collagen type I, III, and IV and fibronectin, decreases in senescent activated HSCs (5). On the other hand, the secretion of ECM-degrading matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), such as MMP1, MMP3, MMP10, and MMP12, enhanced in senescent activated HSCs (5). Senescent IMR-90 cells showed enhanced immune surveillance to a NK cell line (YT cells), facilitating the resolution of fibrosis (5, 8). A matricellular protein (i.e., CCN1) was shown to trigger cellular senescence in activated HSCs, limiting fibrogenesis and promoting liver fibrosis regression (9). In another study, interleukin (IL)-22 binding to IL-10R2 and IL-22R1, which are expressed on HSCs, induced HSC senescence and inhibited liver fibrosis (10). Likewise, IL-10 induced senescence in activated HSCs through the STAT3-p53 pathway and ameliorated liver fibrogenesis (11). The increased expression of MICA and ULBP2 in senescent activated HSCs delivered these cells sensitive to NK cell killing (5).

In addition, activated HSCs downregulate the expression of class I MHC, rendering these cells susceptible to NK cells killing (12). The downregulation of the inhibitory killer immunoglobulin-related receptor (iKIR) gene also enhanced HSC killing by augmenting the activity of NK cells to reduce liver fibrosis (13). The NK cells expressing Killer Cell Lectin-like Receptor Subfamily G Member 1 (KLRG1+) show cytotoxicity against activated HSCs through the TRAIL pathway to limit liver fibrosis progression (14). Primary murine and human HSCs are killed by NK cells in an NKp46-dependent manner to control liver fibrosis (15). Poly I:C–treated NK cells have shown cytotoxicity against activated HSCs, instead of quiescent HSCs, through NK cell receptor natural killer group 2, member D (NKG2D) and Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-dependent pathways to ameliorate liver fibrosis (16). In one study, NK cells were activated by polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly I:C) and IL-18 through the p38/PI3K/AKT pathway to kill HSCs in a TRAIL-dependent manner to promote fibrosis regression (17).

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) belong to the family of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize a variety of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (18, 19). Toll-like receptor-3 is present both in the intracellular space and on the surface of fibroblasts and epithelial cells, but it is localized to the endosomal compartment of myeloid DCs (20). The activation of TLR3 was shown to reduce carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis by activating NK cell cytotoxicity (21). The production of IL-17A by γδ-T cells resulted from exosome-mediated activation of TLR3 in HSCs aggravated liver fibrosis (22). Moreover, TLR3 activation by poly I:C in HSCs and Kupffer cells enhanced the expression of IL-10 and ameliorated alcohol-induced liver injury (23). Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid is a synthetic analog of a double-stranded RNA that can efficiently mimic an acute response to viral pathogens (24). In the mammalian immune system, poly I:C is recognized by transmembrane TLR-3, leading to the expression of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (24).

2. Objectives

In the present study, we investigated the markers of cellular senescence in LX2 cells and primary HSCs after poly I:C treatment. It was shown in our study that TLR3 activation induced cellular senescence in HSCs, triggering NK cell immunosurveillance through upregulating NKG2D ligands. These observations indicated that TLR3 might be a potential therapeutic target in the HSCs-NK cell axis for managing liver fibrosis in humans.

3. Methods

3.1. Cell Extraction

Fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from healthy individuals’ peripheral blood samples by Ficoll density gradient separation. Then NK cells were purified using magnetic cell sorting by a NK Cell Isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

3.2. Cell Culture

Purified NK cells were cultured in a complete medium (RPMI 1640, 10% FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, and glutamine). Primary human HSCs were cultured in Stellate Cell Medium (ScienCell). After that, LX2 cells and primary HSCs were stimulated by poly I:C, then collected, and finally cocultured with NK cells. The experimental groups noted in Figure 1A were as follows:

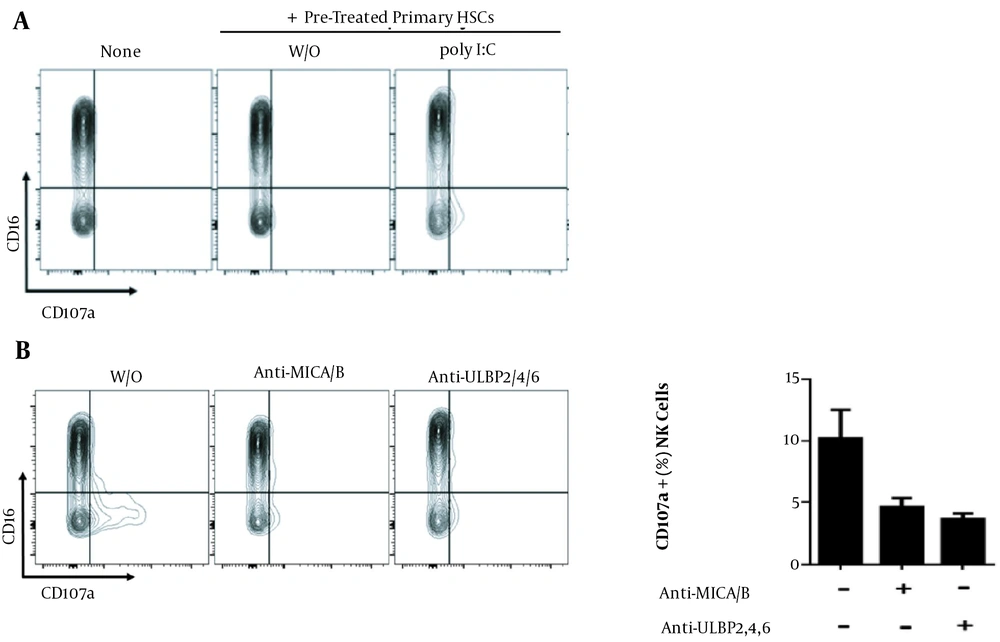

Senescent HSCs trigger immunosurveillance from NK cells through upregulated NKG2D ligands. Primary HSCs stimulated with poly I:C were cocultured with NK cells, the expression of CD107a was detected by flow cytometry. None means only NK cells, w/o means without poly I:C. (A) Primary HSCs were pretreated with Anti-MICA/B and Anti-ULBP2,4,6 before poly I:C stimulation, then cocultured with NK cells, CD107a expression was shown. w/o means without anti-MICA/B or anti-ULBP2/4/6 (B).

None: NK cells were cultured in a fresh complete medium for 5 h and stained with mouse anti-human CD16-APC and mouse anti-human CD107a-FITC.

W/o: Primary HSCs were pre-cultured in a complete medium without Poly I:C for 24 h, which was then replaced with fresh medium. Then NK cells were added to the wells to establish the co-culture system for 5 h. Finally, the cells were stained with mouse anti-human CD16-APC and mouse anti-human CD107a-FITC.

Poly I:C: Primary HSCs were pre-cultured in a complete medium and treated with Poly I:C for 24 h. Then the old medium was replaced with fresh medium without poly I: C, NK cells were added to the wells to create the co-culture system for 5 h. The cells were finally stained with mouse anti-human CD16-APC and mouse anti-human CD107a-FITC.

The experimental groups mentioned in Figure 1B were as follows:

W/o: Primary HSCs were pre-cultured in a complete medium with poly I:C for 24 h. Then the old medium was replaced with a fresh medium without poly I:C, and NK cells were added to the wells to create the co-culture system for 5 h. The cells were finally stained with mouse anti-human CD16-APC and mouse anti-human CD107a-FITC.

Anti-MICA/B: Primary HSCs were pre-cultured in a complete medium with poly I:C and human anti-MICA/B neutralizing antibodies for 24 h. After replacing the old medium with a fresh medium without poly I:C, NK cells were added to the wells to establish a co-culture system for 5 h. Ultimately, staining with mouse anti-human CD16-APC and mouse anti-human CD107a-FITC was performed.

Anti-ULBP2/4/6: Primary HSCs were pre-cultured in a complete medium with poly I:C and human anti-ULBP2/4/6 neutralizing antibodies for 24 h. Then the old medium was replaced with a fresh medium without poly I:C, and NK cells were added to the wells to generate a co-culture system for 5 h. Finally, mouse anti-human CD16-APC and mouse anti-human CD107a-FITC were used for staining.

3.3. Flow Cytometry

Purified NK cells were stained with mouse anti-human CD107a-FITC (BD Pharmingen) and incubated in a culture medium for 5 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Golgi-Plug was added in the last 4 h of incubation, and then the cells were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry for CD107a detection. The following antibodies were used in this experiment: mouse anti-human MICA/B-PE (R & D; catalog number: FAB13001P-025), mouse anti-human ULBP2/5/6-Alexa Fluor 488 (R & D; catalog number: FAB1298G-100UG), mouse anti-human TRAILR4/TNFRSF10D-PE (R & D; catalog number: FAB633P), and mouse anti-human CD16-APC (R & D; catalog number: FAB2546A-025). We used low and high fluorescence controls to normalize raw flow cytometry data and minimize technical measurement variations between experiments. The percentage of positive cells was determined and compared between the control and treatment groups using FlowJo software.

3.4. Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was carried out as described previously (17). Briefly, LX2 cells were collected and lysed by adding the RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling technology) to dissolve proteins. Total cellular protein content was electrophoresed on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and then transferred on PVDF membranes (Merck Millipore). The membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk in TBST and incubated at room temperature for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with anti-p16 (ZEN BIO, catalog number: R22878), anti-p21 (ZEN BIO, catalog number:385235), anti-beta-actin (Cell Signaling technology, catalog number: 4970), and anti-alpha tubulin (Abcam, catalog number: 7291). The membranes were washed by 0.1% tween 20 (Sigma Aldrich) TBS three times for five minutes each time. Finally, peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Proteintech) at a dilution of 1:5000 in TBST was added to the membranes, and incubation continued for another 1 h at room temperature. Western blot immunoreactivity was performed using the ECL kit (Merck Millipore).

3.5. Real-Time PCR

Cells were cultured in a complete medium with (i.e., the experimental group) or without (i.e., the control group) poly I:C. Then mRNA was extracted using EasyPure RNA extraction kit (TRANSGEN), followed by reverse transcription and q-PCR using TransScript II Green Two-Step qRT-PCR SuperMix (TRANSGEN). The thermal cycling of PCR was as follows: 94°C for 30 sec and 42 cycles of 94°C for five sec and 60°C for 30 sec. All qRT-PCR experiments had multiple replicates, and the average value obtained from the control replicates was set as “1” to normalize other experimental values. Finally, mRNA levels were calculated relative to control β-actin using the 2-ΔΔCq method.

3.6. SA-β-gal Staining

Hepatic stellate cells’ senescence was assessed using a SA-β-gal (senescence-associated β-galactosidase) staining kit (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). The cells cultured (for 48 h) in a complete medium without poly I:C were set as control, and poly I:C-treated cells were regarded as the experimental group.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

The independent t-test was performed to compare the variables between the two groups using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Prism software). P values < 0.05 indicated that a difference was statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. TLR3 Mediates Senescence in HSCs

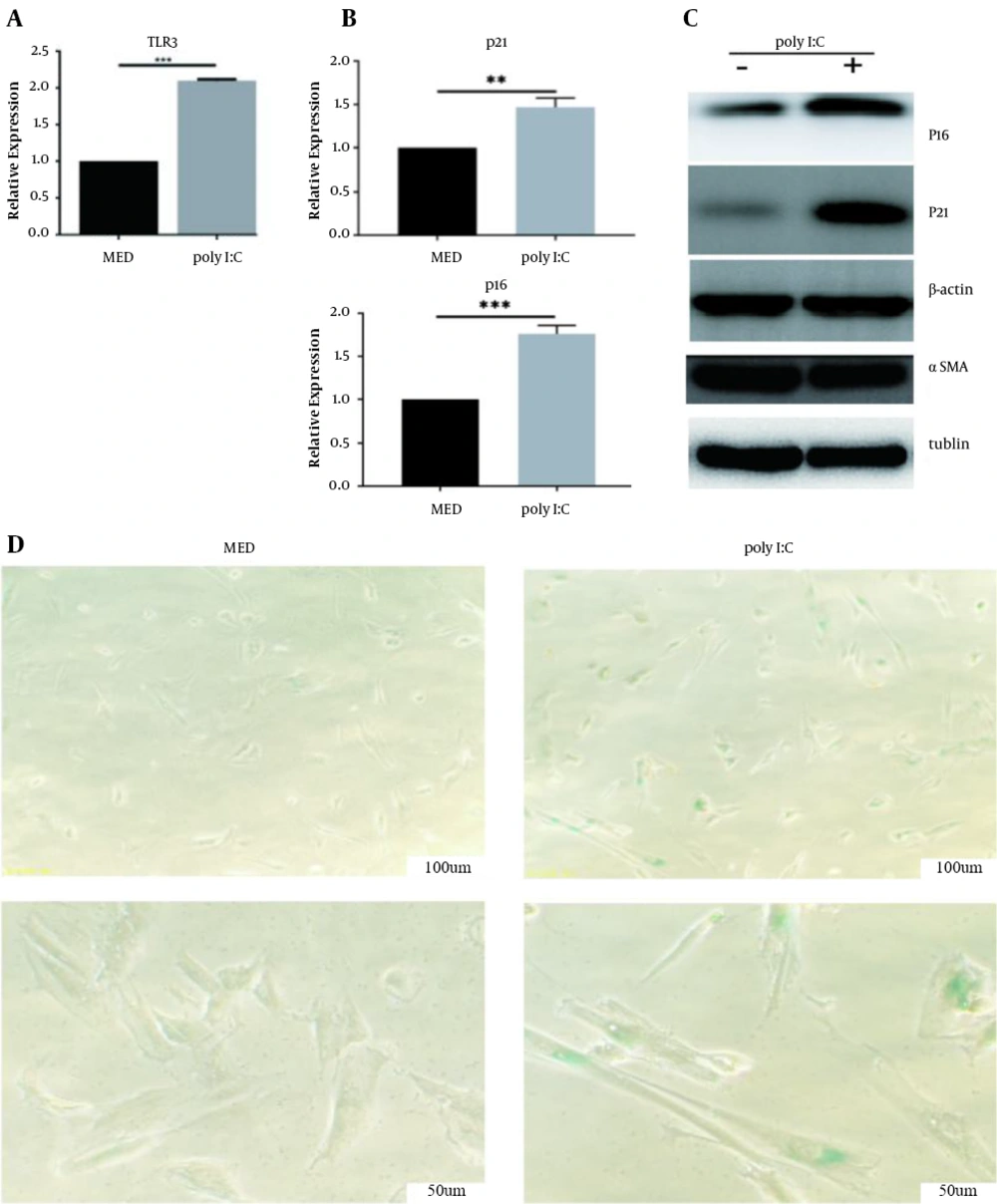

To identify the role of TLR3 activation in cellular senescence, poly I:C (100 µg/mL) was first used to activate TLR3 in primary HSCs. Then qPCR analysis was used, showing that TLR3 mRNA was upregulated in primary HSCs after poly I:C treatment (P < 0.001, Figure 2A). Many researchers have confirmed that high levels of p21 or p16 promote cellular senescence (25). To assess the role of poly I:C in cellular senescence, we treated LX2 cells with poly I:C and analyzed the expression of cellular senescence markers (p16 and p21) in these cells using qPCR and western blot (WB) analysis. The results showed that the mRNA and protein levels of p16 (P < 0.01) and p21 (P < 0.001) markedly increased in poly I:C-treated LX2 cells compared to control (Figure 2B and C). Meanwhile, poly I:C exposure decreased the protein level of α-SMA in LX2 cells (Figure 2C), suggesting that poly I:C inhibited the activation of LX2 cells. To further validate the phenomenon, SA-β-gal expression was assessed in primary HSCs treated with poly I:C via SA-β-gal staining, demonstrating an increase in SA-β-gal level compared to control (Figure 2D). These results suggested that TLR3 ligands directly induced cellular senescence in HSCs.

TLR3 activation induces cellular senescence in HSCs. HSCs were treated with poly I:C at indicated concentration. A, TLR3 expression was measured by qRT-PCR; B, p16 and p21 expression was measured by qRT-PCR; C, Western blot analyses of protein expression of senescence molecules P16, P21 and fibrogenic molecule α-SMA; D, Senescence-dependent β-galactosidase activity staining showing significant upregulation in the poly I:C-treated HSCs. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

4.2. Increased NKG2D Ligand Expression in TLR3-Induced Senescent HSCs

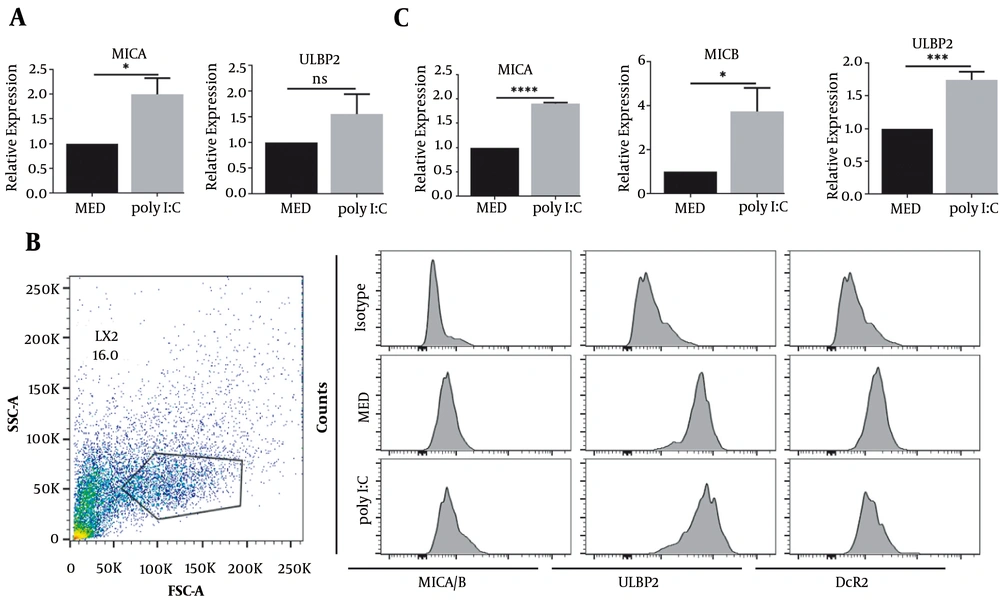

The participation of MICA and ULBP2 proteins is necessary for the recognition of senescent fibroblasts by NK cells (26). We further determined whether or not MICA and ULBP2 were upregulated in poly I:C-treated LX2 cells. Both MICA (P < 0.05) and ULBP2 (P < 0.05) were upregulated at mRNA level in poly I:C-treated LX2 cells (Figure 3A). In concordance with mRNA expression, enhanced MICA/B and ULBP2 proteins’ expression was also observed in poly I:C-treated LX2 cells as determined by fluorescent intensity via flow cytometry (Figure 3B). The ligands of NKG2D, MICA, MICB (P < 0.05), and ULBP2 (P < 0.001), were significantly upregulated in poly I:C-treated primary HSCs compared to control (Figure 3C). These results suggest that TLR3-induced senescent HSCs upregulate the expression of NKG2D ligands.

NKG2D ligands expression was increased in TLR3-induced senescent HSCs. HSCs were treated with poly I:C at indicated concentration. A, MICA and ULBP expression in LX2 cells were measured by qRT-PCR; B, The expression of MICA/B, ULBP and DcR2 in LX2 cells was analyzed by flow cytometry; C, MICA, MICB and ULBP expression in primary HSCs was measured by qRT-PCR. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. ns, not significant.

4.3. Senescent HSCs Trigger NK cell Immunosurveillance by Upregulating NKG2D Ligands

We further determined whether or not the upregulation of NKG2D ligands in poly I:C-treated primary HSCs could enhance NK cell degranulation, which was evaluated by measuring CD107a expression using flow cytometry. The NK cells cocultured with poly I:C-treated primary HSCs showed a significantly higher CD107a expression (Figure 1A). The expression of CD107a was down-regulated when primary HSCs were treated with MICA/B or ULBP2/4/6 inhibitors before being cocultured with NK cells (Figure 1B). These results suggested that senescent HSCs upregulated NKGD ligands, rendering them more sensitive to NK cell killing.

5. Discussion

Poly I:C attenuates liver fibrosis in vivo partly through enhancing TLR3-induced NK cell cytotoxicity (27, 28), selectively killing activated HSCs (17). Poly I:C, as a TLR3 agonist, has been shown to have multiple biological functions in various liver diseases such as HCV infection (29), HBV infection (30), and liver cancer (31), as well as in the hepato-carcinogenesis process (32). It has been demonstrated that poly I:C plays an important role in modulating inflammatory reactions and immune responses in liver diseases. Here, we investigated the effects of TLR3 induction on activated HSCs, as cells expressing TLR3 (33). In this study, we demonstrated that TLR3 activation promoted HSC senescence and enhanced the expression of NKG2D ligands and sensitivity to NK cell cytotoxicity. The upregulation of TLR3 was noted to trigger the senescence of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells by increasing the expression of SA-β-Gal and p21 (34). Our findings also suggested a role for TLR3 in inducing cellular senescence in HSCs. In another study, it was shown that IL 10 increased the expression of p21, which had an important role in inducing senescence in primary rat hepatic stellate cells (35). Autophagy drives senescence in fibroblasts through upregulating the expression of p16 and p21 senescence biomarkers (36). In the present study, the poly I:C treatment of HSCs upregulated the expression of p16 and p21 and increased the number of SA-β-gal-positive cells. To our knowledge, this is the first description of TLR3-induced senescence in HSCs.

Another molecule, NKG2D, plays an important role in the killing of senescent tumors by NK cells, which can be enhanced by p53-dependent chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) (37, 38). The interaction between the NKG2D receptor and its ligand is a key event for NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity against senescent cells (26). In this study, we found that the expression of NKG2D ligands, MICA and ULBP2, increased in TLR3-induced senescent HSCs. A decoy receptor for TRAIL, DcR2, is another senescence marker (39). Even though it encourages cell senescence, it has been reported that the exocytosis of NK cells’ granules towards senescent cells is normally decreased following DcR2 upregulation (40). In our study, the expression of DcR2 on HSCs decreased, indicating that TRAIL may also take part in NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity towards TLR3-induced senescent HSCs. Granule exocytosis, instead of death receptor signaling, is required for NK cell-mediated killing of senescent IMR-90 fibroblasts and primary human hepatic myofibroblasts (40). In the present research, we demonstrated that TLR3-induced HSC senescence could limit hepatic fibrosis via enhancing CD107a expression in the NK cells co-cultured with poly I:C-treated HSCs. On the other hand, poly I:C and IL-18 synergistically activate NK cells to kill HSCs to promote fibrosis regression (17), suggesting a dual role for TLR3 in ameliorating liver fibrosis (i.e., inducing NK cell cytotoxicity and boosting HSC sensitivity to NK cells). In summary, our study revealed that poly I:C sensitized HSCs to NK cell degranulation, suggesting that TLR3 can be a potential target for treating liver fibrosis.