1. Background

Viral hepatitis is one of the important health problems around the world. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is low in Iran, as reported in less than 2% of the general population (1). The infantile vaccination program established in 1993, along with the vaccination of high-risk groups, has shown positive impacts on decreasing the prevalence of HBV infection in the past decade (2).

Iran has low endemicity for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, with a prevalence of less than 0.5% (3). The World Health Organization (WHO) has set the goal to eliminate HCV by 2030 (4). Although new treatment strategies have provided the opportunity for HCV elimination, effective treatments are not yet adequate (5). Also, insufficient knowledge regarding viral hepatitis seems to be a barrier against disease elimination due to the emergence of newly infected cases (5, 6).

It is well known that healthcare workers are exposed to an increased risk of blood-borne diseases (7, 8). In fact, the majority have experienced at least 1 occupational injury in the clinical setting (8, 9). The average risk of disease transmission after needlestick exposure to infected blood has been estimated at approximately 0.3% for HIV, 1.8% for HCV, and 6% - 30% for HBV among healthcare workers (8). Overall, risk of transmission is at the highest level in (bio)medical students during their professional health training (10).

Previous studies have shown that the knowledge of Iranian physicians, medical specialists, and (bio)medical students regarding HBV, HCV, and other blood-borne diseases is not adequate (11-13). Furthermore, iatrogenic transmission remains an important route of transmission for HBV and HCV infections (14, 15).

Improvement of the general population’s knowledge about viral hepatitis is an important step towards disease elimination. Therefore, public awareness campaigns (PACs) may be helpful in this area (5, 6), even in special populations, such as (bio)medical students and healthcare workers (13). Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to evaluate the knowledge level of Iranian (bio)medical students regarding HBV and HCV infections and to determine the effect of a hepatitis PAC, held by the students, on the level of knowledge.

2. Methods

A PAC was planned by Iran Hepatitis Network (IHN) for world hepatitis Day in 2016 (6). This prospective study was performed during this campaign.

2.1. Study Population

We made announcements in social networks for registration in the PAC. A total of 151 (bio)medical students registered primarily in our website to join the PAC. Only students, who participated in both workshop and campaign program, were included in the survey (91 out of 151 students).

2.2. Campaign Program

The campaign had 2 major parts. The first part was a hepatitis workshop, which was held by IHN on July 24, 2016. In total, 91 students participated voluntarily in the workshop and were allowed to enter the program. Two pamphlets in simple Persian language for HBV, HCV, and PAC materials were prepared. The pamphlets comprised of the epidemiology of HBV and HCV infections in Iran, viral hepatitis elimination programs by WHO and IHN (by 2030), general transmission routes and the most important transmission routes in Iran, harm reduction strategies, false beliefs of the general population about HBV and HCV, diagnostic tests, and treatment strategies focusing on new therapies. Also, some free references were introduced for additional information in the website (http://meldcenter.com/book-and-brochur/).

In the second part, the trained students were sent to Tehran metro stations to promote public hepatitis awareness during July 26 - 28, 2016. There were 3 shifts every day (10:00 - 13:00, 13:00 - 16:00, and 16:00 - 19:00) in 4 metro stations simultaneously. The students set their station and time of presence voluntarily. During the PAC, more than 400 face-to-face consultations were done by the students (6).

2.3. Instrument Validation

A questionnaire, including 15 items, was designed by a gastroenterologist, and each item of the questionnaire was scored for necessity, relevance, clarity, and simplicity by 8 other specialists. Then, the content validity ratio (CVR), as well as relevance-, clarity-, and simplicity-content validity indices (R-CVI, C-CVI, and S-CVI), was calculated. All 15 questions were included in the questionnaire, as CVR, R-CVI, C-CVI, and S-CVI were above 0.75 for all of them.

2.4. Survey

All the participating students completed the questionnaire before (pretest, T1) and after (posttest, T2) the workshop. Also, posttest was repeated right after finishing the campaign (final test, T3). Then, the results of T1, T2, and T3 were compared.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences. All the students participated in PAC and completed the questionnaires voluntarily.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The number of correct answers for each question was presented as number and percentage. McNemar’s test was used for the comparison of correct answers to each question between T1, T2, and T3. The total knowledge score was calculated for each participant. Each correct answer was scored 1, while an incorrect answer was scored 0. The total score was calculated as the total score of individual questions and was presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) on a scale of 100. The total knowledge score was compared between T1, T2, and T3 by paired sample t test.

3. Results

In total, 91 (bio)medical students (24 males and 67 females) with the mean age of 21.83 ± 2.24 years (range, 18 - 27 years) enrolled in our program. The participants were undergraduate students of medicine (64.8%), midwifery (6.6%), dentistry (6.6%), nursing (5.5%), pharmacy (4.4%), medical virology (4.4%), anesthesia (3.3%), microbiology (2.2%), and physiotherapy (2.2%). They were students of 7 universities of medical sciences in Tehran province (86.8%) and some other provinces (13.2%). The mean duration of students’ presence in the stations was 5.17 ± 2.98 hours (minimum, 3 hours; maximum, 18 hours during 3 days).

Overall, 54% of the students were unaware of their HBV vaccination status. Only 23.1% of the participants were familiar with the most prevalent HBV transmission route in Iran before the workshop. The proportion of participants with correct answers increased at T2 in comparison to T1. The least significant increase in the number of students with correct answers was observed in Q3 and Q11 (increased from 85.7% - 86.8% to 87.9% - 89%), while the most significant increase was observed for Q15 (increased from 46.15% to 83.5%; Table 1).

| Questions | T1b | T2c | T3d | P1/P2/P3e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1. What is the most prevalent transmission route of HBV in Iran? | ||||

| (1: Unsafe injection / 2f: Mother to infant / 3: Unsafe Barbershops / 4: Unsafe cupping) | 21 (23.1) | 30 (33) | 71 (78) | 0.004/< 0.001 /< 0.001 |

| Q2. What is the most prevalent transmission route of HCV in Iran? | ||||

| (1f: Unsafe injection / 2: Mother to infant / 3: Unsafe Barbershops / 4: Unsafe cupping) | 54 (59.3) | 82 (90.1) | 89 (97.8) | < 0.001/0.016 /< 0.001 |

| Q3. Which one has an effective vaccine? | ||||

| (1f: HBV / 2: HCV / 3: Both / 4: None) | 79 (86.8) | 81 (89) | 91 (100) | 0.500/0.002/< 0.001 |

| Q4. Can a hepatitis B patient marry without transmitting it to his/her spouse? | ||||

| (1f: Yes / 2: No) | 55 (60.4) | 82 (90.1) | 91 (100) | < 0.001/ 0.004/< 0.001 |

| Q5. Can women with hepatitis B become pregnant and give birth to a healthy baby? | ||||

| (1f: Yes / 2: No) | 63 (69.2) | 84 (92.3) | 91 (100) | < 0.001/0.014/< 0.001 |

| Q6. Chronic HBV… | ||||

| (1: Can be cured / 2f: Can be controlled / 3: Both 1 and 2) | 52 (57.1) | 59 (64.8) | 89 (97.8) | 0.016/< 0.001/< 0.001 |

| Q7. Do inactive HBV carriers need treatment? | ||||

| (1: Yes / 2f: No) | 38 (41.8) | 54 (59.3) | 80 (87.9) | < 0.001/< 0.00/< 0.001 |

| Q8HBV and HCV infections can lead to | ||||

| (1: Cirrhosis / 2: Liver cancer / 3f: Both 1 and 2 / 4: None) | 60 (65.9) | 67 (73.6) | 90 (98.9) | 0.017/< 0.001/< 0.001 |

| Q9. Which one is the diagnostic test for HBV? | ||||

| (1: ALT / 2f: HBs-Ag / 3: HBs-Ab / 4: HBe-Ag) | 45 (49.45) | 65 (71.4) | 91 (100) | < 0.001/< 0.001/< 0.001 |

| Q10. Which one is the diagnostic test for HCV? | ||||

| (1: ALT / 2: HBc-Ab / 3f: HCV-Ab / 4: HCV-Ag) | 44 (48.35) | 76 (83.5) | 89 (97.8) | < 0.001/< 0.001/< 0.001 |

| Q11. Which one can transmit HBV and HCV? | ||||

| (1: Unsafe tattooing / 2: Unsafe cupping / 3: Unsafe injection / 4f: All) | 78 (85.7) | 80 (87.9) | 91 (100) | 0.250/0.002/< 0.001 |

| Q12. Which drug is used for the treatment of HBV? | ||||

| (1: PEG-interferon / 2: Tenofovir / 3: Adefovir / 4f: All) | 45 (49.45) | 75 (82.4) | 90 (98.9) | < 0.001/< 0.001/< 0.001 |

| Q13. Which drug is used for the treatment of HCV? | ||||

| (1: Tenofovir / 2: Lamivudine / 3f: Sofosbuvir / 4: All) | 27 (29.7) | 42 (46.15) | 85 (93.4) | < 0.001/< 0.001/< 0.001 |

| Q14. Can kissing and hugging transmit HBV and HCV? | ||||

| (1: Yes / 2f: No) | 64 (70.3) | 82 (90.1) | 91 (100) | < 0.001/0.004/< 0.001 |

| Q15. The minimum serum HBs-Ab titer for protection against HBV is… | ||||

| (1: 5 / 2f: 10 / 3: 100 / 4: 1000) | 42 (46.15) | 76 (83.5) | 90 (98.9) | < 0.001/< 0.001/< 0.001 |

| Total knowledge percentage (0 - 100) | 56.2 ± 18.0 | 75.8 ± 17.9 | 96.6 ± 6.1 | 0.001/0.003/< 0.001 |

aData are described as number (%) and mean ± standard deviation. HCV, hepatitis C virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBs-Ag, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBc-Ab, hepatitis B core antibody; HBs-Ab, hepatitis B surface antibody; HCV-Ab, HCV antibody.

bBefore workshop (pretest, T1).

cAfter workshop (posttest, T2).

dAfter the campaign (final test, T3).

eP value for comparison between T1 and T2 (P1), P value for comparison between T1 and T3 (P2), and P value for comparison between T2 and T3 (P3).

fCorrect answer.

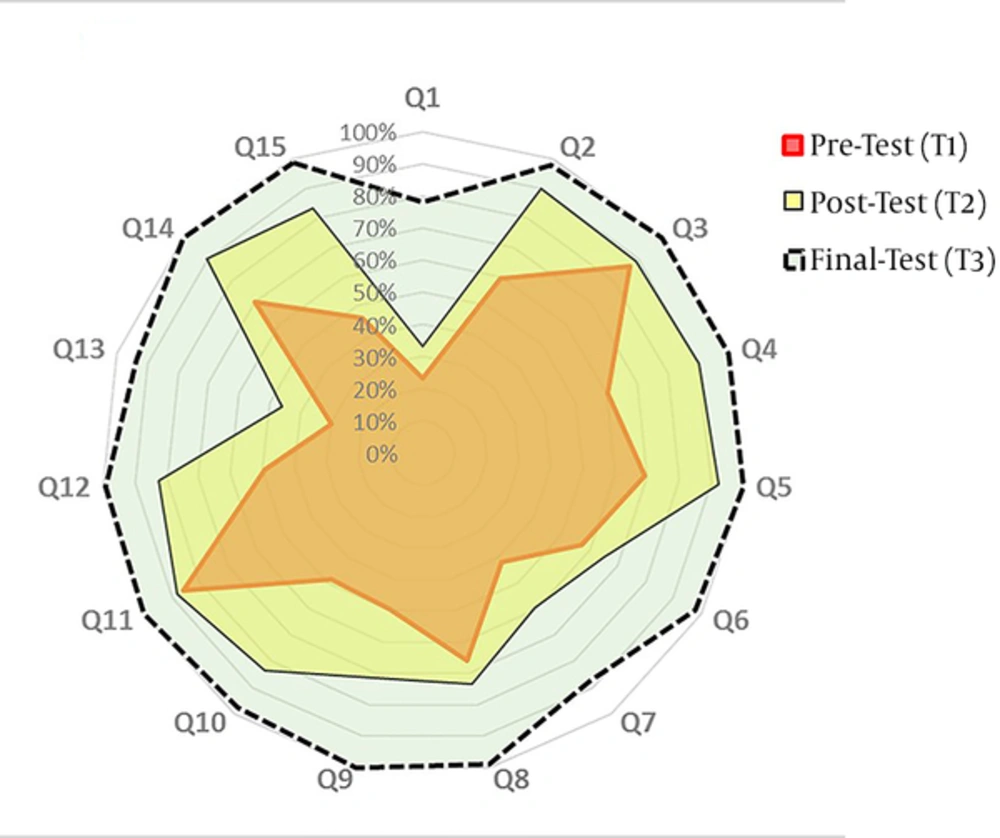

The increase in the proportion of correct answers was not significant for Q3 or Q11 (P > 0.05), while it was significant for all other individual questions (P < 0.05; Table 1, Figure 1). The mean total knowledge scores of the students before and after the workshop were 56.2 ± 18.0 and 75.8 ± 17.9, respectively (P = 0.001).

The number of participants with correct answers increased at T3 in comparison with T2. The smallest increase in the number of participants with correct answers was observed in Q2 and Q5 (increased from 90.1% - 92.3% to 97.8% - 100%), while the largest increase was observed in Q15 (increased from 46.15% to 93.4%; Table 1). The increase in the proportion of correct answers was significant for all individual questions (P < 0.05; Table 1, Figure 1). The mean total knowledge score of the students increased to 96.6 ± 6.1 after the end of the campaign (P = 0.003; Table 1). Regarding 8 questions, PAC could increase the number of participants with correct answers more than the workshop (Q1, Q3, Q6 - Q9, Q11, and Q13; Figure 1).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the level of hepatitis knowledge in a nonrandom sample of (bio)medical students and to determine the effect of PAC on the level of knowledge. The baseline assessment of the students showed that their knowledge was better in some areas, compared to others. About 86-87% of the students were familiar with blood transmission routes and effective vaccination for HBV, while 13% - 14% did not have adequate knowledge. Only 23.1% of the students were aware of the most prevalent transmission route for HCV in Iran, and 29.7% were familiar with accurate treatment for HCV. The present results also demonstrated an increase in the number of participants with correct answers after holding the PAC.

It is well known that healthcare workers are exposed to an increased risk of blood-borne infections (16-18); this risk is at the highest level during their health professional training (10). HBV infection among healthcare workers has been estimated to be 2 to 4 times higher than the general population (10). Chronic HCV infection is also transmitted by blood-to-blood contact either through drug use or more commonly through healthcare procedures.

A great deal of the global burden of HCV has been attributed to medical professions. Today, we have the opportunity to find and treat infected patients and control disease transmission (14, 15). WHO has proposed a plan for the elimination of viral hepatitis by 2030 (4, 19), and public awareness seems to be an important step in these programs to avoid person-to-person transmission and help find the unknown cases (5, 6). This awareness is more important in high-risk groups, such as (bio)medical students, compared to other groups; therefore, effective measures should be taken for this important issue in Iran.

The T1 results demonstrated that the general knowledge of Iranian undergraduate (bio)medical students regarding HBV and HCV infections was inadequate. This finding was in congruence with previous studies regarding hepatitis knowledge of Iranian (bio)medical students (11, 13). In addition, most of the students had passed at least 1 course about blood-borne diseases and harm reduction. Moreover, comparison of T1 and T2 results showed that theoretical, educational programs, such as hepatitis workshops, could increase the proportion of participants with correct answers; however, this increase was insufficient.

In a study on the medical interns of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, 25.6% and 32.1% of the participants had 1 and 2 - 4 accidental exposures to blood, respectively. Only 17.6% of the participants always wore gloves during the procedure, and only 5.5% never recapped the needle; in total, 87.5% of the subjects were vaccinated against HBV (20). In this regard, in a study in Cameroon, 55.9% of medical students had accidental exposure to blood, and 54% were not vaccinated against HBV (21). Also, 89% of healthcare workers were unvaccinated for HBV in Tanzania, which could be attributed to unawareness, inadequate knowledge, or impractical knowledge (22).

Among 961 (bio)medical students in Vientiane, only 21% were fully immunized for HBV, and 9.1% received only 1 or 2 doses of vaccine. The main reason for non-vaccination was that they did not know where to get vaccinated. More than 72% of the surveyed students were unable to correctly answer any of the 5 questions about HBV (agent of hepatitis B, mode of HBV transmission, risk factors for hepatitis, main symptoms, and complications); also, 37% were aware of being at risk of HBV infection (7).

In the present study, the number of participants with correct answers increased to 19.6% after the workshop and further increased to 20.8% through PAC. Comparison of T2 and T3 results for individual questions also indicated that correct answers can dramatically increase (up to 100%) by holding a social program, such as PAC, after the theoretical educational program. The students were motivated to read more about HBV and HCV infections during the campaign to answer people’s questions regarding hepatitis. Also, they were encouraged to read more resources after finishing the campaign.

HBV vaccination is included in Iran’s national immunization program for neonates and is strictly enforced. Nevertheless, it is only recommended for healthcare workers and is not strictly enforced for (bio)medical students (20, 23). The present survey showed that 54% of the students were unaware of their HBV vaccination status. They also did not have enough knowledge about their hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) titer for protection against HBV. All (bio)medical students, who were enrolled in our program, were HBV-vaccinated, according to the national vaccination program for HBV vaccination of neonates and adolescents (23). The (bio)medical students and other high-risk groups should ensure protection against HBV through testing HBsAb titer routinely (24).

4.1. Limitations

The present study could not compare the effects of PAC and workshop separately. Nevertheless, it was clear that PAC provides some extra knowledge for the students and increases their level of knowledge. Assessment of knowledge immediately after the campaign might be biased, as it did not evaluate knowledge retention. Also, the study sample was not selected randomly, which might have affected the baseline evaluation of knowledge; therefore, we suggest a national survey on this subject.

4.2. Conclusion

The present results demonstrated that knowledge regarding HBV and HCV infections is inadequate among Iranian undergraduate (bio)medical students. The inadequacy of knowledge can lead to iatrogenic transmission or infection and postpone the elimination of viral hepatitis due to the emergence of new cases. Also, the proportion of correct answers increased up to 100% through holding a social program, such as PAC, after the theoretical educational program. Therefore, we suggest using social activities and campaigns to increase awareness among (bio)medical students. In addition, further national studies are required to confirm the reported findings.