1. Background

The hepatitis C virus (HCV), a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Flaviviridae family, significantly contributes to liver diseases. The complications of chronic HCV infection vary widely, from minimal damage to hepatic cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Factors such as infection persistence, male gender, alcohol consumption, infection at an older age, and insulin resistance play crucial roles in the development of the disease (1-3). Genetic factors also influence infection outcomes across different populations (3). For instance, African Americans with chronic HCV infection are at a higher risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma and have a lower likelihood of recovery (4). Cytokines, produced by resident and infiltrating macrophages, are essential mediators of the immune response in hepatic infections, inducing inflammatory responses that lead to liver damage and fibrosis.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pleiotropic cytokine produced by various cell types, including leukocytes and endothelial cells, and is involved in a wide range of actions, including hematopoiesis, carcinogenesis, and inflammatory responses (5). The IL-6 gene is located on chromosome 17, and several polymorphisms have been identified in the promoter region of IL-6. These polymorphisms can regulate IL-6 production and are associated with a broad spectrum of diseases, including gastric (6), colorectal (7, 8), and prostate cancers (9, 10), juvenile idiopathic arthritis (11), meningococcal diseases and metabolic syndrome (12).

Different single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at positions −597 G/A (rs1800797), −572 G/C (rs1800796), and −174 G/C (rs1800795) in the IL-6 promoter have been identified to affect IL-6 transcription. The polymorphism at −174 G/C has been the subject of most studies. While Barrett et al. reported a relationship between HCV and IL-6 promoter polymorphisms, other studies have not confirmed such an association (13). Research conducted on South American populations found no link between this polymorphism and chronic HCV infection when compared with a control group (14). However, one study did indicate an association between the −174 G/C polymorphism and HCV infection. The −572 C/G and −597 G/A polymorphisms have been linked to a broad spectrum of diseases, including cancer, autoimmune diseases, and hepatitis. Relatively few studies have examined the connection between HCV and IL-6 promoter polymorphisms. This investigation aimed to determine whether the major polymorphic position in the IL-6 promoter (-174 G>C) is associated with HCV infection in our population.

2. Objectives

Given that genetic predispositions might influence susceptibility to HCV infection, exploring genetic variations is crucial. This study sought to analyze the genotype and haplotype distribution of the IL-6 gene at the (-174 G>C) position among HCV-infected patients and healthy individuals to determine whether IL-6 gene polymorphisms could affect the risk of HCV infection.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population

This case-control study was conducted as a cross-sectional survey on 71 patients with chronic HCV infection and 79 healthy subjects serving as the control group in Mashhad, located in the northeast of Iran. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for hepatitis B virus (HBV) was administered to all participants, and those testing positive for HBsAg were excluded from the study. Subsequently, a total of 146 individuals were recruited to participate in the investigation and then divided into two groups: 67 patients suffering from chronic HCV and 79 individuals in the control group. The diagnosis of HCV infection in patients was confirmed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Delaware Biotech, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA). The HCV viral load was determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). All participants were informed about the objectives of the research project. The study received ethical approval from the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee. Consent forms were obtained from all study participants. A 10 mL sample of peripheral blood was collected from each participant into tubes containing EDTA. Hepatitis C virus antibodies were qualitatively assessed using a commercial ELISA kit, and HCV-positive results were further confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using HCV-specific primers. All HCV-infected patients underwent evaluation by a liver specialist.

3.2. Laboratory Investigations

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in patients infected with HCV and control subjects were measured using a commercial kit (Pars Azmoon, Iran). According to the manufacturer's instructions, ALT levels below 31 U/L for females and 41 U/L for males were deemed normal.

3.3. DNA Extraction

Samples were obtained from peripheral blood mononuclear cells collected in tubes containing EDTA. DNA extraction was carried out using commercial kits (Genet Bio, Korea).

3.4. Genotyping for IL-6 Gene Polymorphisms

The genetic analysis of the IL-6 gene's polymorphic position was conducted using the ARMS-PCR method. For this analysis, forward primers 5'-CCC TAG TTG TGT CTT GCG-3' (for detection of the G allele) and 5'-CCC TAG TTG TGT CTT GCC-3' (for detection of the C allele), along with a reverse primer 5'-GAG CTT CTC TTT CGT TCC-3', were utilized. The PCR experiment was performed under the following conditions: An initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 minute, 58°C for 1 minute, 72°C for 1 minute, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 minutes. Polymerase chain reaction amplification for the IL-6 -174 G>C polymorphism was executed in a 20 μl reaction volume that included 40 ng of genomic DNA, 10 mM of each dNTP, 25 mM MgCl2, 1 μL of 10 pmol of each primer, and 5 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Genet Bio, Korea) in 10X Reaction Buffer. The PCR products were then visualized by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with Green Viewer (Pars Tous, Iran) (15, 16).

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 21 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test assessed the normality of the data. Differences in gender, addiction, alcohol consumption, transfusion, and tattoo operation between HCV patients and controls were evaluated using the chi-square test. The logistic regression method was utilized to determine the association between the -174 G>C position of the IL-6 gene in HCV-infected patients and healthy controls, calculating odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Difference between values were considered significant when a two-tailed P was <0.05. was analyzed using χ2 test. A p-value less than 0.05 were considered significant.

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

The age range of the study group was 16 to 62 years, with a mean age of 42.15 ± 10.66, comprising 59 males and 8 females (M: F = 6.4). In the control group, ages ranged from 15 to 65 years, with a mean age of 36.33 ± 12.55, including 32 males and 47 females. Table 1 presents additional demographic data for the HCV-infected patients and the control group. HCV genotyping was conducted according to the methodologies described by Ohno et al. and Aborsangaya et al. (17, 18). All participants in the study were tested for HIV infection, with results showing all subjects and individuals representing the general population were negative. In the control group, there were neither drug addicts nor individuals with tattoos, whereas in the patient group, there were 30 addicts and 21 tattooed individuals. The percentage of transfusions was 41.71% in patients and 10.12% in controls.

| Characteristics | HCV-Infected Patients | Controls | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male: Female ratio | 59: 8 | 32: 47 | < 0.05 |

| Age (y) a | 42.15 ± 10.66 | 36.33 ± 12.55 | < 0.05 |

| Addiction | 30 | 0 | < 0.05 |

| Alcohol | 29 | 2 | < 0.05 |

| Transfusion | 28 | 8 | < 0.05 |

| Tattoo | 21 | 0 | < 0.05 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, UL-1 a | 35.42 ± 31.96 | 26.97 ± 21.89 | 0.3 |

| Increased alanine aminotransferase b | 18 | 17 | < 0.05 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b > 41 UL-1 for men and > 31 UL-1 for women.

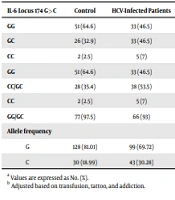

4.2. IL-6 -174 G/C polymorphism

Genetic analysis for the IL-6 -174 G>C polymorphism was performed on all HCV-infected patients and control subjects. Table 2 shows the distribution of IL-6 -174 G>C genotypes and alleles among the cases and controls, with genotypes adhering to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The GG genotype was the most common in both groups, whereas the CC genotype was the least frequent (GG 46.5% vs. 64.6%; GC 46.5% vs. 32.9% [P = 0.44; OR = 1.97, 95% CI: 0.35 - 10.98]; CC 7% vs. 2.5% [P = 0.12; OR = 3.87, 95% CI: 0.71 - 21.09]). The odds ratio (OR) for the CC genotype was 3.84 (95% CI 0.71 - 21.09), indicating no significant difference.

| IL-6 Locus 174 G>C | Control | HCV-Infected Patients | Crude P-Value | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted P-Value b | Adjusted OR (95% CI) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG | 51 (64.6) | 33 (46.5) | Ref | |||

| GC | 26 (32.9) | 33 (46.5) | 0.44 | 1.97 (0.35 - 10.98) | 0.44 | 1.97 (0.35 - 10.98) |

| CC | 2 (2.5) | 5 (7) | 0.12 | 3.84 (0.71 - 21.09) | 0.12 | 3.84 (0.71 - 21.09) |

| GG | 51 (64.6) | 33 (46.5) | 0.027 | 0.48 (0.25 - 0.92) | 0.08 | 0.40 (0.14 - 1.12) |

| CC/GC | 28 (35.4) | 38 (53.5) | ||||

| CC | 2 (2.5) | 5 (7) | 0.21 | 2.91 (0.55 - 15.53) | 0.21 | 2.91 (0.55 - 15.53) |

| GG/GC | 77 (97.5) | 66 (93) | ||||

| Allele frequency | 0.024 | 0.11 | ||||

| G | 128 (81.01) | 99 (69.72) | 0.54 (0.32 - 0.92) | 0.51 (0.22 - 1.16) | ||

| C | 30 (18.99) | 43 (30.28) | 1.85 (1.09 - 3.16) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Adjusted based on transfusion, tattoo, and addiction.

According to Table 2, the frequencies of the GG genotype and the combined CC/GC genotypes among the cases were 46.5% and 53.5%, respectively, and for the CC genotype and combined GG/GC genotypes, they were 7% and 93%. In contrast, the frequencies in the control group were 64.6% and 35.4% for GG and CC/GC genotypes, respectively, and 2.5% and 97.5% for CC and GG/GC genotypes. No significant difference in genotype frequencies was observed between cases and controls after adjusting for confounders. The frequency of the G allele was 81 . 01% in the control group and 69 . 72% in the case group, while the frequency of the C allele was 18.99% in controls and 30 . 28% in cases. A significant difference in allele frequencies between the two groups was only noted before adjustment (P = 0.024). The confounding factors considered were transfusion, tattooing, and addiction

5. Discussion

Interleukin-6, an IL that acts as a pro-inflammatory cytokine, is produced by various cells, including B-cells, T-cells, and fibroblasts. It impacts hematopoiesis, the functionality of immune system cells, and cell inflammation (19). IL-6 activates through two signaling pathways. The classic pathway involves IL-6 interacting with its receptor (IL-6R), typically found on the cell surface of hepatocytes and specific leukocytes (20-22). This interaction leads to the formation of a homodimer from a signal-receiving component known as gp130, creating the IL-6-IL-6R complex. This complex initiates the activation of Janus kinase (JAK1), which then phosphorylates the intracellular protein gp130. Janus kinase subsequently activates a transcription factor known as STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription) through phosphorylation.

In the trans-signaling pathway, a soluble form of IL-6R binds with a free IL-6 group, allowing this complex to signal any cell that possesses gp130 on its surface, which is nearly ubiquitous. The regulation of the soluble form of IL-6R is not fully understood, but its production through either mRNA splicing or proteolytic cleavage from the cell surface has been recognized. A single nucleotide polymorphism at position -174 in the IL-6R promoter relates to two alleles, G and C (11). Gene transfection studies have shown that allele G is expressed 60% more than allele C, indicating that it is a more active promoter for inducers such as IL-1 and endotoxin.

This polymorphism has been associated with two phenotypes. The first is a high-level producer phenotype, which encompasses the -174 G/G and -174 G/C genotypes and is characterized by a production cycle that exceeds the IL-6 level. The second phenotype is a low-level producer associated with the -174 C/C genotype. Significant racial differences have been observed in the frequency of the G allele, which is notably higher in non-Caucasian populations than in Caucasian ones (23, 24). Specifically, the first group, comprising African, Native American, and Singapore Chinese populations, shows a G allele frequency ranging from 0.87 to 1. In contrast, the second group, which includes Spanish, Northern Irish, and European American populations, exhibits a G allele frequency between 0.54 and 0.62.

In this study, a significant difference in allele frequency at the IL-6 -174 G>C polymorphism was observed between HCV-infected patients and the control group. Both groups exhibited a lower frequency of the recessive alleles associated with this polymorphism. When examining genotype frequencies, it was found that the frequency of the low-level producer phenotype, associated with the -174 C/C genotype, was similar in both HCV-infected patients and the control group. However, these findings among HCV-infected patients differ from those reported by Barrett et al., who investigated the same polymorphism in an Irish population (25). In that study of Caucasian HCV-infected individuals, a correlation was identified between the CC genotype (low-level producer phenotype) and HCV clearance.

In a recent study, Yee et al. (26) demonstrated that American HCV-infected patients carrying IL-6 haplotypes C and A at the -174 G>C and -597 G > A positions, respectively, exhibited a more sustained response to antiviral treatments for chronic HCV infection. However, these findings contradicted those reported by Pereira et al. (14), who observed no differences in the frequencies of alleles and genotypes of polymorphisms at the -174 G>C position of the IL-6 gene between American HCV-infected patients and the control group. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that Pereira et al. found a significantly lower frequency of the genotype C/C in the control group, which aligns with our findings.

In a study by Ali Deeb et al. (27), the association between IL-6 (-174G/C), (-597G/A), and (-572G/C) promoter polymorphisms and serum IL-6 levels in HCV patients was investigated. They observed a significant increase in the -174GG genotype in the healthy group compared to the patient group.

Falleti et al. (28) conducted a study in 2010 on patients with HCV and persistently normal transaminases (PNALT) to explore disease progression. They documented a connection between the high-producer genotype (GG) in the IL6 – 174 polymorphism and a more unfavorable progression of HCV infection.

Additionally, a study in 2015 investigated the influence of the IL-6 (−174) C allele on HCV clearance but did not find any genetic association between the IL-6 (-174G/C) SNP and susceptibility to HCV infection (29).

Minton et al. (30), along with Park et al. in 2003 (31), Ribeiro et al. in 2007 (32), Migita et al. (33), and Chang et al. (34) in a meta-analysis, did not find support for the involvement of the IL-6 (-174G/C) SNP in HCV clearance. Chang et al.'s (34) meta-analysis specifically showed that the lack of association between the (-147G/C) IL-6 polymorphisms and the outcome of chronic HCV infection might be attributed to the near absence of the C allele of -174GC polymorphism in East Asian and South American populations. Since the objective of the study was to determine the association between the -174 G>C polymorphism of the IL-6 promoter and the risk of chronic hepatitis C infection, few relevant data were available concerning the issue. In contrast, there are many studies regarding the relationship between the polymorphisms of the IL-6 promoter and the outcome of chronic HBV infection. Although they vary in some cases, there is a consensus that the correlation between the polymorphism of IL-6 promoter (particularly the polymorphism of IL-6 -174 G>C) and the results of chronic HBV treatments is evident (31, 33, 35, 36). However, all these investigations have demonstrated the low frequency of recessive alleles of promoter polymorphism, especially those with the polymorphism of allele C at -174 G>C position. Additionally, further studies are recommended to investigate other common promoter polymorphisms (−1363 G > T, −597 G > A, −572 G>C, +2954 G>C).

Based on our findings, the polymorphism of the -174 G>C position of the IL-6 gene may confer some degree of risk in HCV-infected patients. Therefore, individuals carrying the C allele may be susceptible to this disease. Considering that the required sample size was obtained using standard statistical formulas, we conducted our study on the recruited patients. However, it is suggested that future studies use a larger sample size, as this will help with better interpretation of the data and provide more reliable results.