1. Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection poses a significant global health challenge, affecting an estimated 296 million individuals worldwide, with over 820 000 annual deaths from liver-related complications (1). Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Achieving seroclearance of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is a crucial therapeutic objective due to its association with prolonged survival and reduced incidences of cirrhosis and HCC (2). Consequently, the suppression of viral replication and subsequent HBsAg seroclearance are the primary objectives in the treatment of CHB (3). On the other hand, the persistence of HBsAg is a known risk factor for chronic liver diseases and HCC (4). However, HBsAg loss is a rare occurrence with current antiviral therapies, and spontaneous loss of HBsAg is infrequent, approximately 1% per year, among untreated adults with CHB infection (5). In some cohorts, advanced age and inactive HBsAg carrier status have been identified as the sole predictors of HBsAg seroclearance (6). Nevertheless, the precise factors influencing HBsAg loss remain incompletely understood.

Obesity has been identified as a risk factor for the progression of fibrosis in chronic liver diseases (7). Several studies have shown a strong association between elevated body mass index (BMI) and the presence of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in patients with HBV infection and HBV DNA suppression (8, 9). However, the coexistence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and CHB may synergistically impact the liver, increasing the risk of fibrosis and HCC (8). In a study involving patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and CHB, a baseline BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 and weight gain were identified as predictors of incident NASH (10). Some rodent models have suggested that calorie restriction can reduce inflammation and levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Weight loss has been shown to decrease hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) in the short term, suggesting its potential as an additional treatment strategy (11).

Moreover, there has been a growing interest in understanding the relationship between HBV infection and hepatic lipid metabolism, as HBV is regarded as a “metabolic virus” affecting various hepatic metabolic processes. However, the precise mechanisms by which HBV impacts lipid metabolism in hepatocytes remain incompletely understood (12). The relationship between HBV and lipid metabolism is complex, and further clinical and basic studies are necessary to determine this relationship (13).

Coffee, known for its high antioxidant content, has been suggested that it may be effective in improving insulin sensitivity and preventing metabolic syndrome (14). In a study, those who consumed 4 or more cups of coffee daily experienced a 70% decrease in serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and liver fibrosis index values compared to non-coffee drinkers in individuals with HBV infection (15). Epidemiological studies have revealed a dose-dependent protective effect of coffee against HCC, with daily coffee consumption associated with a risk reduction ranging from 30% to 80% compared to non-drinkers (16).

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate lifestyle-related factors that may contribute to HBsAg loss in patients with CHB, with a particular focus on the relationship between weight loss and HBsAg seroclearance.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study employed a retrospective approach to evaluate the HBsAg status and clinical and laboratory findings in patients with CHB, alongside a cross-sectional analysis to assess their lifestyle factors. Ethical approval was granted by the Sakarya University Faculty of Medical Ethics Committee (reference number: 050.01.04/304; approval date: September 16, 2019).

A total of 5600 patients aged 18 and over who were followed up with a diagnosis of HBV infection between January 2008 and January 2020 at the Infectious Diseases Polyclinic of Sakarya University Training and Research Hospital were examined. Chronic hepatitis B patients with HBsAg loss were identified.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were retrieved from the hospital database. All participants (94 patients with HBsAg loss and 95 with HBsAg persistence) were surveyed using a questionnaire developed by the authors to inquire about the lifestyle characteristics of CHB patients.

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

To be included in the study, patients had to meet several criteria: They had to be aged 18 or older, diagnosed with chronic hepatitis with or without treatment, and have a follow-up period of at least 3 years, with a minimum of 1 year of follow-up after HBsAg loss if seroconversion occurred. Additionally, they needed to voluntarily participate in the survey developed by the authors to investigate the lifestyle characteristics of patients and be accessible for the survey.

Exclusion criteria: Patients who were followed for less than 3 years after CHB diagnosis and those with incomplete follow-up and laboratory data; being under 18 years old; HBsAg seroclearance following acute hepatitis; co-infection with HCV, hepatitis D virus (HDV), or HIV; prior or ongoing immunomodulatory or immunosuppressant therapy; malignancy; metabolic liver disease; alcoholic liver disease; drug-induced liver disease; autoimmune liver disease; cirrhosis; end-stage liver failure; HCC; liver transplantation; pregnancy; and breastfeeding. Additionally, patients who could not be contacted to obtain information about their lifestyle habits were excluded from the study.

3.3. CHB Patient Selection with HBsAg Loss

A total of 5600 patients aged 18 and over who were diagnosed with HBV infection and followed up at the Infectious Diseases Polyclinic of Sakarya University Training and Research Hospital between January 2008 and January 2020 were examined. Among patients diagnosed with HBV, 171 patients who developed HBsAg seroconversion were identified. Twenty-seven patients who developed seroconversion following acute hepatitis B were excluded. Of the remaining patients, 144 demonstrated confirmed CHB with spontaneous or antiviral-induced HBsAg seroconversion. According to the inclusion criteria, patients who were followed for at least 3 years after CHB diagnosis and at least 1 year after HBsAg seroconversion were included in the study.

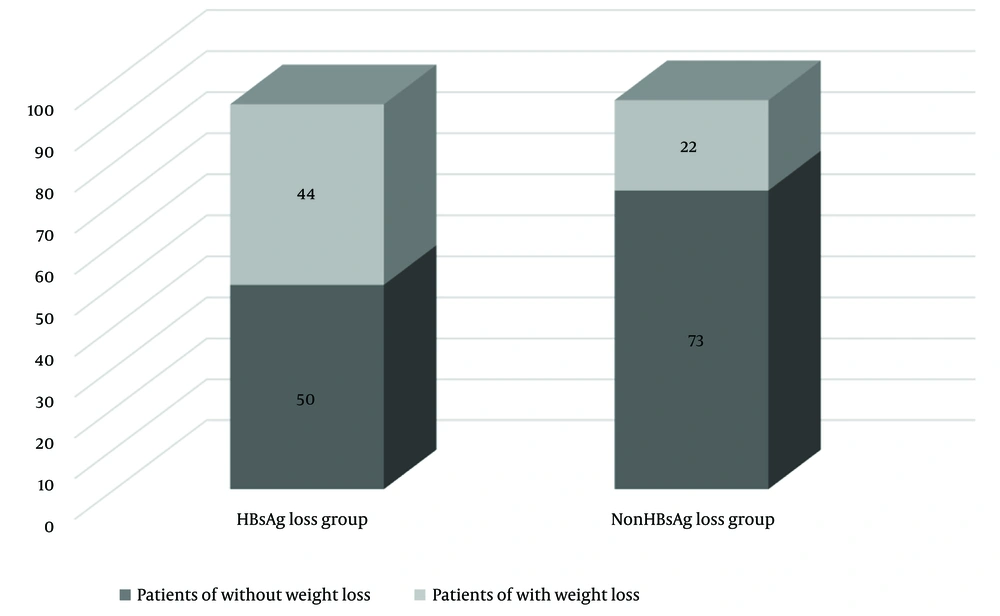

Ten patients were excluded due to inadequate data (n = 10), while 19 did not meet the inclusion criteria (malignancy [n = 6], concurrent use of immunosuppressants [n = 6], HCV [n = 1], HIV coinfection [n = 2], other hepatic diseases [n = 4]). After determining the number of patients with HBsAg loss, they were contacted by phone, and those who volunteered were asked to visit the hospital for questioning. However, 21 patients were unreachable. Patients whose lifestyle habits were questioned were included in the study. The HBsAg loss group consisted of 94 CHB patients who met the inclusion criteria and voluntarily participated in the study by responding to the inquiry form (Figure 1). In the HBsAg loss group, 94 patients were included in the study.

3.4. CHB Patient Selection Without HBsAg Loss

A total of 95 patients without HBsAg loss were matched as controls. Patients in this group were consecutively selected from CHB patients attending scheduled follow-up visits at our outpatient clinic who remained HBsAg-positive. Patients with a minimum of 3 years of follow-up after CHB diagnosis were included in the study. The non-HBsAg loss group consisted of 95 CHB patients who met the inclusion criteria and volunteered to participate.

3.5. Lifestyle Assessment Questionnaire

All participants (94 patients with HBsAg loss and 95 with HBsAg persistence) were administered a questionnaire created by the authors to inquire about the lifestyle characteristics of CHB patients. Patients selected according to exclusion criteria were contacted by phone, and those who volunteered to participate in the study were called to the hospital.

The questionnaire covered topics such as the use of herbal products, antiviral treatments, concomitant diseases, medication use, coffee consumption, and weight changes. Patients were questioned about weight changes, including weight loss or gain through diet or exercise. Additionally, weight data and BMI data recorded in patient follow-up files were accessed retrospectively.

In patients diagnosed with CHB, the BMI level (kg/m2) was calculated at baseline and in the last period before HBsAg loss. Similarly, the initial and final BMI levels were calculated in the group without HBsAg loss.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, obesity is defined as a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher in adults. A BMI between 25 and 29.9 (BMI ≥ 25 - 29.9) is classified as overweight. A BMI of 30 kg/m2 is classified as obese, and this group was further divided into moderate obesity (30 - 34.9 kg/m2), severe obesity (35 - 39.9 kg/m2), and very severe obesity (≤ 40 kg/m2) (17).

Weight loss was classified as less than 5 kg (< 5), between 5 kg and 15 kg (5 - 15), between 15 kg and 25 kg including more than 15 (> 15 - 25), more than 25 kg (> 25). Weight gain was classified as less than 5 kg (< 5), between 5 kg and 15 kg (5 - 15), between 15 kg and 25 kg including more than 15 (> 15 - 25), more than 25 kg (> 25).

Coffee consumption was classified as follows: 1 - 2 cups per week, 1 cup per day, 2 cups per day, and more than 2 cups per day.

3.6. Hepatosteatosis Assessment

As hepatic steatosis grades may change over time, they were assessed during the 3 years preceding HBsAg seroclearance and during the period following HBsAg seroclearance. Hepatic steatosis grades were determined through hepatic ultrasonography and graded from 0 to 3 (0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe) based on hepatic echogenicity.

3.7. Laboratory Methods

Serum HBV DNA detection was performed using a fully automated real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (Rotor-Gene Q 5Plex HRM, Qiagen). Hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-HBs, HBeAg, and anti-HBe antibodies were tested using radioimmunoassay or enzyme immunoassay (Abbott Diagnostics, North Chicago, IL., USA).

3.8. Statistical Methods

The data were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL., USA). For quantitative variables, the Student's t-test was used, and for categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. A paired samples t-test was used to compare dependent samples, specifically for comparing the baseline and last period BMI means of the HBsAg loss group and non-HBsAg loss group. The statistical significance level was set at a P-value less than 0.05.

4. Results

A total of 189 patients participated in this study, with 94 patients in the HBsAg loss group and 95 patients in the non-HBsAg loss group. In the HBsAg loss group, 76% were inactive HBsAg carriers, while 71% in the non-HBsAg loss group were inactive hepatitis B carriers (no significant difference).

Among the 94 patients in the HBsAg loss group, 24% experienced HBsAg seroconversion due to antiviral treatment, while 76% had spontaneous HBsAg seroconversion.

There was no significant difference in gender distribution between the 2 groups, with 52% of patients in both groups being male (no significant difference). The average age was 48.3 years in the HBsAg loss group and 47.4 years in the non-HBsAg loss group (no significant difference; Table 1).

| Characteristic | HBsAg Loss Group (n = 94) | Non-HBsAg Loss Group (n = 94) | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 48.3 ± 12.9 | 47.4 ± 10.4 | > 0.05 |

| ≤ 50 years patients | 55 (59) | 54 (57) | > 0.05 |

| Gender | > 0.05 | ||

| Female | 45 (48) | 46 (48) | |

| Male | 49 (52) | 49 (52) | > 0.05 |

| Inactive HBsAg carrier | 72 (76) | 67 (71) | > 0.05 |

| Without cirrhosis | 94 (100) | 95 (100) | > 0.05 |

| HBeAg negativity | 73 (78) | 82 (86) | > 0.05 |

| Baseline HBV DNA (IU/mL) | 435899.28 ± 3568114 | 44664775.04 ± 279044953 | < 0.001 |

| Baseline HBV DNA of inactive HBsAg carrier (U/mL) | 2616.82 ± 16606 | 962986.97 ± 690297 | < 0.001 |

| Baseline ALT (U/L) | 26.95 ± 34.79 | 32.19 ± 34.79 | > 0.05 |

| Abnormal ALT (> 36 U/L) | 11 (12) | 20 (21) | > 0.05 |

| Baseline AST (U/L) | 24.78 ± 18.35 | 31.68 ± 32.47 | > 0.05 |

| Abnormal AST (> 34 U/L) | 8 (9) | 12 (13) | > 0.05 |

| Baseline PLT count (h/mL) | 232170 ± 64.57 | 246910 ± 64.92 | > 0.05 |

| HAI | 6.1 ± 3.4 | 5.65 ± 2.6 | > 0.05 |

| Fibrozis | 2 ± 0.66 | 1,94 ± 0.58 | > 0.05 |

| The period after the CHB diagnosis (y) | 13.8 ± 5.8 (3 - 26 years) | 12.03 ± 5.6 (3 - 30 years) | > 0.05 |

| Duration of antiviral treatment (y) | 6.42 ± 4.1 | 7.47 ± 2.8 | > 0.05 |

| Total anti-HBs positivity | 54 (57) | 0 (0) | 0,001 |

| Anti-HBs positivity in inactive CHB patients | 41 (44) | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| Anti-HBs positivity in patients who used NUC | 13 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| NUC used | 22 (23) | 28 (29) | > 0.05 |

| Lamuvidine | 6 (6) | 7 (7) | > 0.05 |

| Tenofovir (TDF) | 6 (6) | 17 (18) | 0.01 |

| Entecavir | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | > 0.05 |

| PEG-interferon | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | > 0.05 |

| Use of interferon and antiviral | 6 (6) | 4 (4) | > 0.05 |

| Use of tenofovir after lamivudine | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | > 0.05 |

Abbreviations: HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; PLT, platelet; NUC, nucleot(s)ide analogue.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The baseline mean histological activity index (HAI), fibrosis, HBeAg negativity, and levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), AST, and platelet (PLT) did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (no significant difference; Table 1).

The mean baseline HBV DNA level was significantly lower in the HBsAg loss group (435899.28 IU/mL) compared to the non-HBsAg loss group (44664775.04 IU/mL; P < 0.001). Student’s t-test, was used to compare means.

A paired samples t-test was used to compare dependent samples, specifically for comparing the baseline and last period BMI means of the HBsAg loss group. The mean baseline BMI in the HBsAg loss group was 28.93 kg/m2, decreasing to 27.42 kg/m2 in the last period (P < 0.001; Figure 2).

Similarly, in the non-HBsAg group, baseline and last period BMI means were compared with paired samples t-test. In contrast, there was no significant change in the mean BMI in the non-HBsAg loss group (no significant difference). Although the mean baseline BMI in the non-HBsAg loss group was 27.8 kg/m2, it was also 27.89 kg/m2 in the last period (P > 0.05; Figure 2).

The chi-square test was used for categorical variables. The number of obese patients (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) increased significantly in the non-HBsAg loss group compared to the HBsAg loss group in the last period (P < 0.05; Table 2).

| Characteristic | HBsAg Loss Group (n = 94) | Non-HBsAg loss Group (n = 95) | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 28.93 ± 5.6 | 27.8 ± 5.4 | > 0.05 |

| Last period BMI (kg/m2) | 27.42 ± 5.2 | 27.89 ± 4.7 | > 0.05 |

| Baseline overweight (BMI ≥ 35 - 39.9 kg/m2) | 26 (28) | 29 (31) | > 0.05 |

| Last period overweight (BMI ≥ 25 - 29.kg/m2) | 31 (32) | 37 (39) | > 0.05 |

| Baseline obesity (BMI ≥ 30 - 34.9 kg/m2) | 29 (31) | 29 (31) | > 0.05 |

| Last period obesity (BMI ≥ 30 - 34.9 kg/m2) | 18 (19) | 31 (33) | < 0.05 |

| Baseline hepatic steatosis | 46 (49) | 32 (34) | < 0.05 |

| Grade 1 (mild) hepatic steatosis | 24 (26) | 23 (24) | > 0.05 |

| Grades 2 - 3 (severe) hepatic steatosis | 22 (23) | 9 (9) | < 0.05 |

| Baseline total cholesterol level | 201.29 ± 46.87 | 195.46 ± 50.05 | > 0.05 |

| Baseline LDL-cholesterol level | 129.51 ± 35.95 | 123.2 ± 36.81 | > 0.05 |

| LDL-cholesterol ≥ 130 mg/dL | 37 (39) | 16 (17) | < 0.001 |

| Diagnosis of hyperlipidemia | 35 (37) | 19 (20) | 0.008 |

| Hyperlipidemia treatment | 11 (12) | 7 (7) | > 0.05 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (11) | 7 (7) | > 0.05 |

| Blood hypertension | 11 (12) | 10 (13) | > 0.05 |

| Polypharmacy | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | > 0.05 |

| Herbal product use | 24 (25) | 8 (8) | 0.001 |

| Current coffee consumption | |||

| 1 - 2 cups of coffee/week | 45 (48) | 40 (42) | > 0.05 |

| 1 cup of coffee/day | 23 (24) | 20 (21) | > 0.05 |

| 2 cups of coffee/day | 8 (8) | 11 (11) | > 0.05 |

| > 2 cups of coffee/day | 6 (6) | 7 (7) | > 0.05 |

Abbreviations: HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; BMI, body mass index; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Weight loss history was more common in the HBsAg loss group, with 47% having a history of weight loss in the last period compared to 23% in the non-HBsAg loss group (P < 0.001; Figure 3). Notably, 36% of patients in the HBsAg loss group had lost between 5 kg and 15 kg , while only 16% of patients in the non-HBsAg loss group experienced such weight loss (P = 0.001). Conversely, weight gain was more prevalent in the non-HBsAg loss group, with 29% gaining weight compared to baseline, compared to only 11% in the HBsAg loss group (P = 0.001; Table 3). Weight loss history was more common in female in the HBsAg loss group (21%) than in the non-HBsAg loss group (10%; P = 0.01). Conversely, weight gain history was also lower in female in the HBsAg loss group (6 %) than in the non-HBsAg loss group (19%) (P < 0.05; Table 3).

| Characteristic | HBsAg Loss Group (n = 94) | Non-HBsAg Loss Group (n = 94) | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss | |||

| Total | 44 (47) | 22 (23) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 24 (26) | 13 (14) | > 0.05 |

| Female | 20 (21) | 9 (10) | 0.01 |

| < 5 kg | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | > 0.05 |

| 5 - 15 kg | 34 (36) | 15 (16) | 0.001 |

| > 15 - 25 kg | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | > 0.05 |

| > 25 kg | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | > 0.05 |

| Put on weight | |||

| Total | 10 (11) | 28 (29) | 0.001 |

| Male | 4 (4) | 10 (11) | > 0.05 |

| Female | 6 (6) | 18 (19) | < 0.05 |

| < 5 kg | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | > 0.05 |

| 5 - 15 kg | 7 (7) | 19 (20) | 0.01 |

| > 15 - 25 kg | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | > 0.05 |

| > 25 kg | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | > 0.05 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Hepatic steatosis (fatty liver) was more prevalent in the HBsAg loss group, with 49% of patients showing basal hepatic steatosis, compared to 34% in the non-HBsAg loss group (P < 0.05). Furthermore, moderate to severe hepatic steatosis was more common in the HBsAg loss group (23%) compared to the non-HBsAg loss group (9%; P < 0.05).

While the baseline mean low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels were similar between the 2 groups (no significant difference), a higher percentage of patients in the HBsAg loss group had LDL-C levels of 130 mg or above (39%) compared to the non-HBsAg loss group (17%; P < 0.001). Hyperlipidemia was also more prevalent in the HBsAg loss group (37%) compared to the non-HBsAg loss group (20%; P < 0.001).

The use of herbal products was significantly more common in the study group (P = 0.001), although each patient used different herbal products. There were no significant differences in coffee consumption history or daily coffee intake between the 2 groups (no significant difference; Table 2).

Additionally, there were no statistical differences in medication usage for comorbidities or CHB treatment between the groups (no significant difference; Table 2).

5. Discussion

In our study, we investigated the factors affecting HBsAg loss in CHB patients and observed a higher rate of HBsAg loss in inactive hepatitis B carrier patients (76%). This finding is consistent with a previous study that identified advanced age and inactive HBsAg carrier status as predictors of HBsAg clearance (6). However, in our study, age was not associated with HBsAg loss.

Our results also revealed that the mean baseline HBV DNA levels were significantly lower in the HBsAg loss group, consistent with another study that highlighted the importance of low HBV DNA levels as a predictor of HBsAg seroclearance (18). Moreover, CHB patients with low baseline HBV DNA levels observed a higher rate of HBsAg seroconversion in a different study (19).

Chu and Liaw reported that factors such as age, gender, normal ALT levels, initial HBeAg negativity, and initial HBV DNA negativity predicted HBsAg seroclearance (20). In a separate study of CHB patients, HBsAg seroconversion was associated with BMI, HBe status, quantitative HBsAg, and baseline HBV DNA levels (21).

We observed a significant decrease in the mean baseline BMI of the HBsAg loss group in the last period before seroconversion (P < 0.001). The mean baseline BMI in the HBsAg loss group was 28.93 kg/m2, decreasing to 27.42 kg/m2 in the last period. Although the mean baseline BMI in the non-HBsAg loss group was 27.8 kg/m2, it was also 27.89 kg/m2 in the last period (P > 0.05).

While the number of obese patients was similar at baseline between the 2 groups, in the last period the number of obese patients (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) decreased significantly in the HBsAg loss group (n = 18; 19%) and increased significantly in the non-HBsAg loss group (n = 31; 33%; P < 0.05).

A study reported a significantly higher prevalence of obesity in the HBsAg seroclearance group compared to the HBsAg persistence group (9). A large cohort study in Taiwan called the “REVEAL-HBV study” found that BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 was a significant determinant of HBsAg serum clearance in CHB patients (22).

This suggests that HBsAg loss in CHB patients may be related to a history of weight loss due to obesity (P < 0.001). Specifically, patients stated that they initiated diets and exercise regimens to lose weight due to obesity, resulting in rapid weight loss over a short period. Notably, 36% of patients in the HBsAg loss group had lost between 5 kg and 15 kg , while only 16% of patients in the non-HBsAg loss group experienced such weight loss (P = 0.001). Conversely, weight gain was more prevalent in the non-HBsAg loss group, with 29% gaining weight compared to baseline, compared to only 11% in the HBsAg loss group (P = 0.001). Weight loss history was more common in female in the HBsAg loss group (21%) than in the non-HBsAg loss group (10%; P = 0.01).

A randomized controlled trial was conducted to investigate cytokine-related effects of aerobic exercise and changes in body fat fraction in individuals with CHB and hepatic steatosis (23). IL-6, a cytokine, may be consistently elevated in patients with obesity and following infection and exercise. IL-6 is produced by the contraction of muscle fibers during exercise and released as a myokine into the bloodstream (24). Several studies have shown that IL-6 could suppress HBV replication and inhibit HBV entry (25). In addition, weight reduction reduces the serum level of leptin, which has pleiotropic effects on immune cell activity (26). In a prospective study conducted with a group of CHB patients who achieved weight reduction with exercise programs, it was observed that weight loss modulated immune system parameters (27).

However, in a study, decreased BMI at 6 months after bariatric surgery in CHB patients with obesity (n = 34) was not associated with changes in HBV DNA levels (28).

In our study, the incidence of mild hepatosteatosis was similar between the 2 groups, while moderate and severe hepatosteatosis was significantly higher in the HBsAg loss group (P < 0.05). According to a study, high BMI and moderate to severe hepatic steatosis may contribute to HBsAg seroclearance in chronic HBV infection. In this study, mild hepatosteatosis was not associated with HBsAg seroclearance, but moderate or severe hepatosteatosis was associated with HBsAg clearance at a rate that was 3 to 4 times higher (9).

According to another study, in HBsAg carriers with high BMI, hepatic steatosis may accelerate HBsAg seroclearance by approximately 5 years (29).

It has been suggested that significant fatty infiltration in the liver, which can alter the cytoplasmic distribution of HBsAg, may contribute to HBsAg seroclearance in CHB virus infection (9). The proposed mechanisms for HBsAg seroconversion associated with hepatic steatosis include changes in the cytoplasmic distribution of HBsAg due to hepatic steatosis or steatosis-induced apoptosis and inflammation in patients with hepatic steatosis (29, 30).

Animal studies in immunocompromised mouse models have shown that hepatosteatosis can inhibit HBV replication (31, 32). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease can promote the spontaneous clearance of HBsAg by enhancing T cell response and TLR4-mediated innate immune response (13). Saturated fatty acids (SFAs) serve as a potential ligand for TLR4 and activate the TLR4 signaling pathway, which may play a role in pathogenesis. A study randomized HBV transgenic mice into HBV and HBV/NAFLD groups and induced NAFLD in HBV transgenic mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) for 8 to 24 weeks. Therefore, HFD resulted in increased circulating SFA levels; this increase activated TLR4/MyD88 signaling, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. TNF-α and IL-6 levels were elevated in the HBV transgenic mice with experimental NAFLD, suggesting that IL-6 and TNF-α may inhibit HBV replication. Compared to the HBV group, significant reductions in serum levels of HBsAg, HBeAg, and HBV DNA titers occurred in the HBV/NAFLD group at 24 weeks, but the IFN-β level was remarkably increased (33).

In our study, the number of patients with LDL-C levels above 130 mg was significantly higher in the HBsAg loss group than in the non-HBsAg loss group at baseline (P < 0.001). Additionally, the prevalence of hyperlipidemia was higher in the HBsAg loss group compared to the non-HBsAg loss group (P = 0.008). Cholesterol is essential for the HBV envelope and plays a critical role in HBV infectivity and viral particle release (34). The results of a cohort study conducted in Korea showed that serum HBsAg positivity was associated with hypercholesterolemia and LDL-C levels (23).

The mechanisms of how HBV infection affects hepatic lipid metabolism have also been investigated in a number of studies based on mouse models. These studies showed that HBV replication or expression causes extensive and diverse changes in hepatic lipid metabolism. It activates certain critical lipogenesis and expression of cholesterol formation-related proteins, as well as regulates fatty acid oxidation and bile acid synthesis. Additionally, studies have found some potential targets for inhibiting HBV replication or expression by decreasing or increasing some lipid metabolism-related proteins (35). Other studies have found that in mouse models, HBV replication or expression increases the lipid biosynthesis-related factor sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP1c) (36).

The proposed mechanisms for HBsAg seroclearance related to hepatic steatosis include the activation of fatty acid catabolism by hepatic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α, which may both suppress HBV replication and alter fatty acid metabolism in obese patients with hepatic steatosis (37, 38).

In patients with CHB, the seroconversion rate of HBsAg with interferon therapy is higher than that with nucleoside/nucleotide analogs, and interferons can induce weight loss as a side effect (39). Interferon therapy can also lead to changes in lipid metabolism, including a significant decrease in total cholesterol and HDL-C levels (40). In a study conducted on CHB patients, it was found that the change in serum cytokine profile with the addition of PEG-IFN-α to the treatment was associated with the loss of HBsAg (41).

In our study, the usage of herbal products was significantly more common in the HBsAg loss group (P = 0.001). However, the types of herbal products used varied among patients. Previous research has indicated that Chinese herbal formula treatments can reduce HBV replication, promote HBeAg clearance, and facilitate seroconversion (42). Additionally, milk thistle with artichoke extract was found to have potential effects on liver damage in patients with alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C liver disease (43).

Comparing the HBsAg loss group to the non-HBsAg loss group, there was no statistically significant difference in coffee consumption (P > 0.05). High coffee consumption has consistently been associated with a lower risk of significant liver fibrosis (44). However, in our study, the rate of individuals who consumed 2 or more cups of coffee daily was relatively low.

5.1. Limitations

The limitation of the study was its retrospective nature. Patient information was documented during their follow-up visits, typically scheduled every 3 - 6 months. Patients were contacted by phone and questioned about their lifestyle habits, weight changes, and whether they experienced weight loss or gain through diet or exercise. Additionally, weight data recorded in the patients' follow-up files were accessed retrospectively.

However, it is important to note that the diagnosis and grading of hepatic steatosis in our study relied on liver ultrasonography, which may present a limitation.

In conclusion, our study identified several factors associated with HBsAg seroclearance in CHB patients, including being an inactive carrier, low baseline HBV DNA levels, hepatosteatosis, hyperlipidemia, and the usage of herbal products. Moreover, HBsAg seroclearance was significantly associated with a history of weight loss and the avoidance of weight gain, particularly in obese patients. Weight management in CHB patients warrants further evaluation. Based on our findings, we recommend that CHB patients, especially those who are obese, consider weight loss as a potential strategy. Further research is needed to explore the molecular changes in lipid metabolism that may contribute to HBsAg seroconversion in CHB patients. Understanding these mechanisms may offer insights into the treatment of CHB.

![Body mass index (BMI) change in the control group [non-hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss group] and HBsAg loss group Body mass index (BMI) change in the control group [non-hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss group] and HBsAg loss group](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/3170b/e2abeb7f583e93361b1407a9e5c3bb4bb0c95059/hepatmon-142264-i002-F2-preview.webp)