1. Context

Most clinical complications associated with hepatitis B are manifested in conditions, particularly cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as consequences of chronic infection. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common in the world and the third leading cause of cancer-related death (1). An effective vaccine has been available for more than two decades, which has decreased the prevalence of HBV infection worldwide dramatically. The primary goal of hepatitis B prevention is reduction of chronic HBV infection and HBV-related chronic liver disease. A secondary goal is prevention of acute hepatitis B. In 1991, the World Health Organization recommended that all countries include hepatitis vaccine in their routine infant immunization program, especially in areas where hepatitis B is endemic (2). The global reported decline in HBsAg prevalence, especially from HBV endemic area (such as South East Asia, Alaska, etc.) has been come as something of a surprise. This falling off has been discussed in depth elsewhere (3). Naively speaking, one would expect that the ultimate decline is reaching; however, this is not the case; universally, about 5-20% of vaccine failure among recipients has been reported manifested by different levels of hypo- or nonresponsiveness to HBV vaccination (4, 5). Historically, the potency of immune response after immunization against hepatitis B has been assessed by measuring antibody to HBsAg. The persistence of anti-HBs above the protection level (> 10 IU/mL) in vaccine recipient is the main goal. This persistence declines by age, particularly, during the first years after vaccination (6). On the other hand, a growing body of literature has shown that HBV vaccine-induced immunologic memory lasting persists more than 15 years after immunization (7, 8).

In 1989, Iranian Ministry of Health launched an immunization program in four provinces as a pilot plan. Subsequently, in 1993, the immunization was extended to all provinces. This has led to 98% coverage of all infants nationally. Afterwards, many researches conducted on the level of response to HBV vaccine among Iranian children and ample data on the coverage rate of vaccine together with evaluation of vaccine responsiveness published in Iran so far. In this study, a systematic review and meta-analysis was performed to provide the statistic power on investigations performed nationally and to provide a summary of the results.

2. Evidence Acquisition

We performed a comprehensive search on PubMed, ISI, Scopus, Iran Medex and Scientific Information Database (SID), on published describing anti-HBs levels in children below 15 years (after six months to 15 years old) who received three doses of HBV vaccine following EPI. All published data from 1994 to August 2014 included in this review.

2.1. Outcomes of Interest and Definitions

The primary outcome was frequency of persons with protective levels of anti-HBs (> 10 IU/mL) following HBV vaccination. The secondary outcome was frequency of nonresponders to HBV vaccine (< 10 IU/mL).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Date Extraction

The main inclusion criterion was all studies that included subjects under 15 years old who received 3 doses of HBV vaccine (regardless of type and brand of vaccines). We limited our investigation to apparently healthy participants and no previous HBV infection. We excluded all studies in which individuals received vaccine episodes out of vaccination schedule (less or more administrations) and in those with any medical interventions (such as using adjuvant, booster doses etc.). Moreover, we did not include surveys that investigated responsiveness to vaccine in those with medical conditions (children born to HBsAg positive mothers, thalassemia, dialysis, received HB vaccine plus immunoglobulin, predisposing factors for immunodeficiency such as HIV, etc.).

2.3. Data Extraction

Data was extracted from selected studies including the name of author, year of publication, the mean age of participants and the levels of anti-HBs in different case-studied. Subjects were divided into two categories: responders who showed anti-HBs levels > 10 IU/mL and nonresponders (anti-HBs < 10 IU/mL). We merged the subjects who harbored levels between two extremes; 10 and 100 IU/mL, as responders (because some studies assigned these levels as hypo-responsiveness). Age and genders of participants were analyzed. Number of HBsAg and anti-HBc positive cases also included in data analysis. The medical subject headings (Mesh) including Entry Terms of PubMed and Emtree of Scopus with affiliation to “Iran” for searching in English databases (HBV vaccine, Anti-HBs, Expanded program on vaccination, prevalence, responders and nonresponders) were used for conducting a more efficient search. Persian keywords equivalent to their English terms were used for searching in national search engines. The references of selected citations and non-published national surveys were hand-searched. The authors assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using a risk-of-bias tool. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion among the authors until a consensus was reached. Studies that had an adequate handling of incomplete outcome data, were free of selective reporting, included an adequate intervention description, had appropriate criteria for participant recruitment and included an adequate outcome explanation were considered low-bias risk trials. The studies with one or more unclear or inadequate quality component were considered high-bias risk trials.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data was collected according to a standard protocol independently by two authors. The authors were not blinded to the names of studies’ authors, journals and results. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion among the authors until consensus was reached (Kappa coefficient: 78%). Data are expressed as percentages for categorical variables and means and SDs (standard deviation) for continuous variables. Statistical heterogeneity of reported prevalence was explored by Chi-square (χ2 or Chi2)-based Q-test and was regarded to be statistically significant at the 10% significance level (P < 0.10). To gain better insight into the prevalence of dyslipidemia and its heterogeneity throughout Iran, we analyzed our findings using random-effects model with a 95% confidence interval (CI). We also used the I2 statistic to quantify inconsistency in results between the studies. The analyses were conducted with STATA software, version 11.0, Produced by StataCorp, the USA.

3. Results

Twenty-eight eligible articles were found in the literature review, all were potentially related to the Iranian EPI. Table 1 shows summary of Iranian studies on immunization program. In total, these investigations were performed on 11639 children who received full three doses of vaccine. The age of subjects was between 6 months and 15 years old with the mean age of 5.21 ± 3.64 years. Overall, 5991 were male (51.5%) and 4571 females (48.5%). Overall, 9311 (80%) responded to vaccine (anti-HBs > 10 IU/mL). On the other hand, 2328 (20%) were nonresponders (anti-HBs < 10 IU/mL). The mean titers of antibody for responders and non-responders were 287.05 ± 332.80 IU/mL and 4.08 ± 1.70 IU/mL, respectively which was statistically significant (P = 0.024). Among responders, the mean anti-HBs titers showed differences between a cut-off of three years old; 500.95 ± 484.19 and 164.82 ± 139.44 IU/mL for those who were under 3 years old versus children more than 3 years old. However, this issue did not reach statistically significant (P = 0.109).

Meta-regression analysis showed that with increase in age, the number of responders to vaccine decreased significantly (P = 0.001) (Table 2). Put another way, the number of nonresponders to vaccine increased as age of vaccines increased (P < 0.001). The other finding was that between years 1995 and 2014, there was no significant difference in the mean anti-HBs titers between studies (P = 0.428).

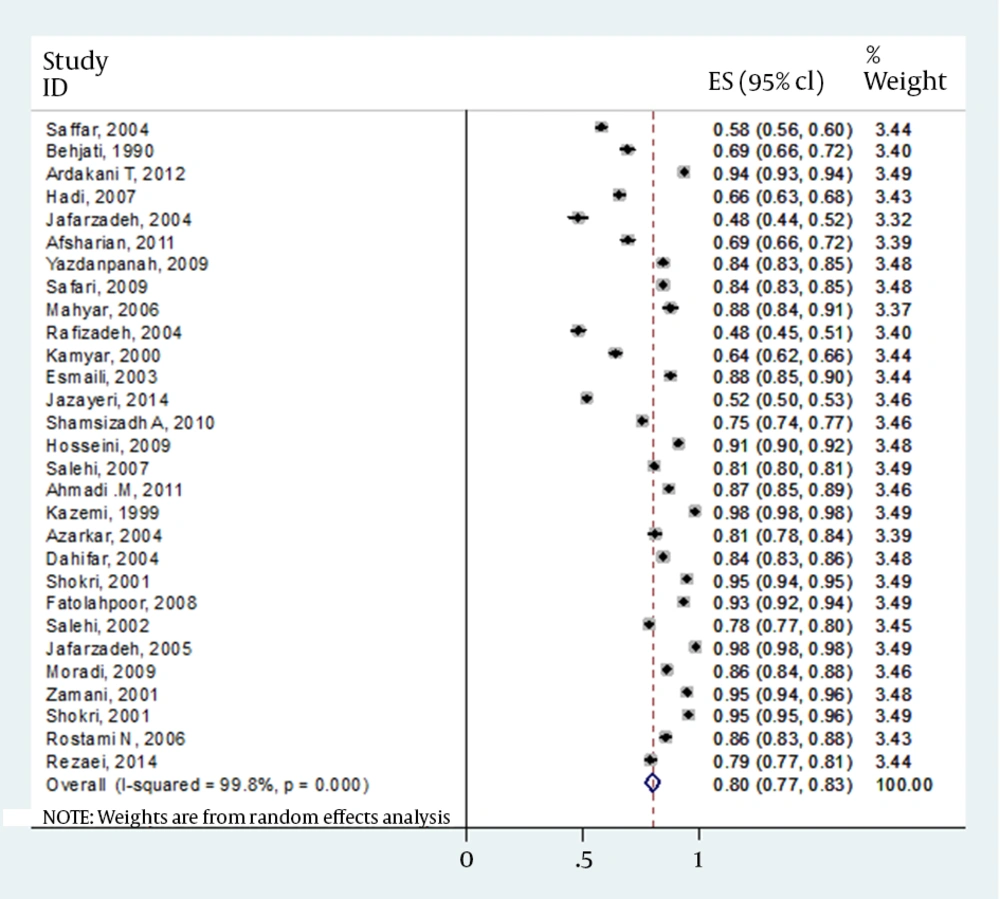

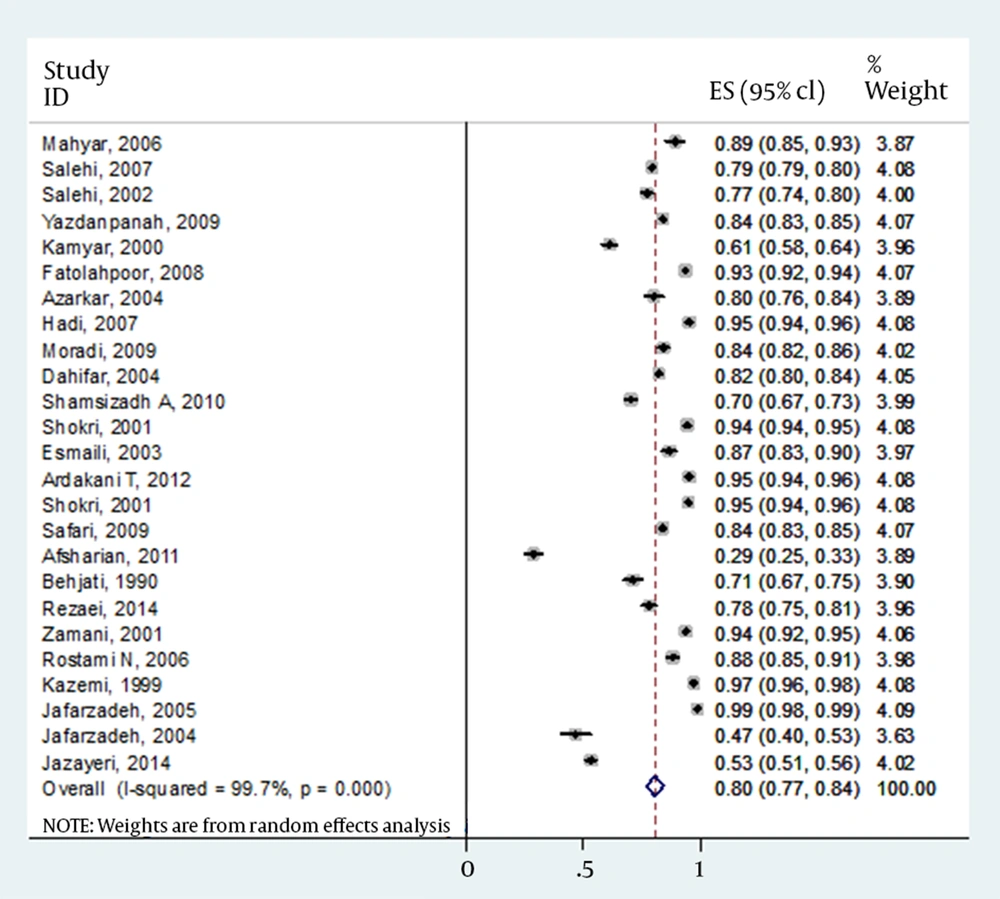

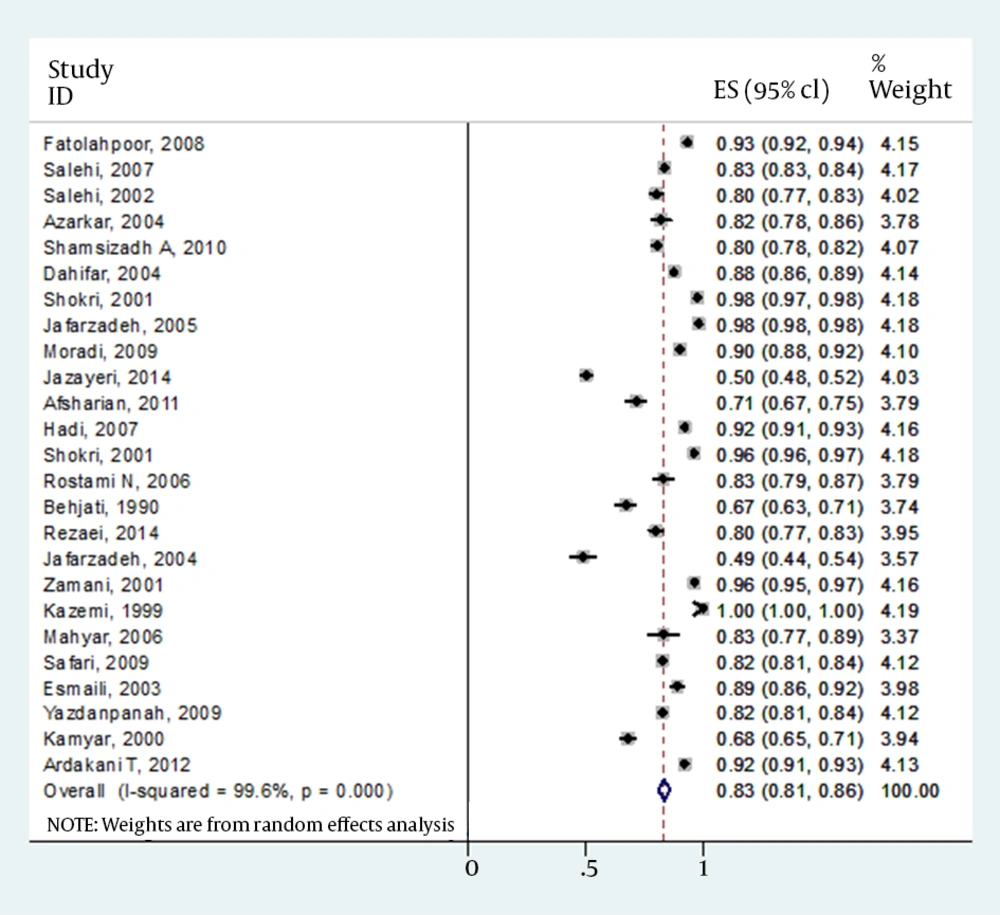

The details of gender for responders versus nonresponders were missed in four articles. However, results from 24 publications indicated that of total 10562 children, 5070 (56.3%) of males and 3937 (43.7%) of females had antibody levels of >10 IU/mL. In contrast, 1346 (59.0%) and 938 (41.0%) of males and females had antibody levels of <10 IU/mL, respectively. Final result for meta-analysis and model performed for total estimated prevalence is shown in Table 3. However, there was no strong difference between responders versus nonresponders to vaccine (P = 0.119). Forest plot of prevalence of HBV vaccine responsiveness in Iranian general, male and female population is shown in Figures 1-3, respectively.

Despite some studies did not specify the type of vaccine used, using different vaccines (Heberbiovac, Cuba; Engerix-B, GSK; Recombivax, Cuba; Euvax B) with the same protocol for vaccine doses and administrations, did not show any significant differences regarding response rate to vaccine (P < 0.001).

Only three studies contained the data on HBsAg prevalence between subjects. The rates ranged between 0 and 1.29% (Table 1). Furthermore, prevalence of anti-HBc was between 0 and 7.5% in different reports (Table 1).

In those studies which compared the rate of responsiveness to HBV vaccine between urban and rural area, no significant differences were found between responders and nonresponders (results not shown). No significant complications and side effects were reported after vaccine administration (results not shown).

Response to vaccine according to ethnic groups (Turkish, Arab, Kurdish, Turkmen, etc.) and geographic area was evaluated; however, no strong correlations were found (P 0.826 and 0.896, respectively).

| Author (s) | No. of Samples | Region | Mean Age, y | Type of Vaccine | HBsAg | Anti-HBc | Prevalence of Responsiveness a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saffar et al. (9) | Mazandaran | 10-11 | Engerix - B | NI | NI | 262 (57.8) | |

| T | 453 | ||||||

| Behjati et al. (10) | Yazd | 8 | NI | NI | NI | ||

| Tb | 200 | 69 | |||||

| M | 100 | 71 | |||||

| F | 100 | 76 | |||||

| Taghavi Ardakani et al.(11) | Isfahan | 14 | NI | 0 | 4% | ||

| T | 200 | 93.5 | |||||

| M | 100 | 95 | |||||

| F | 100 | 92 | |||||

| Hadi et al. (12) | Fars | 6-9 | NI | NI | NI | ||

| T | 374 | 65.6 | |||||

| M | 196 | 66.3 | |||||

| F | 178 | 64.5 | |||||

| Jafarzadeh et al.(13) | Kerman | 10-11 | Engerix - B GSK | NI | 11 (7.5) | ||

| T | 146 | 47.9 | |||||

| M | 58 | 46.6 | |||||

| F | 88 | 48.9 | |||||

| Afsharian et al. (14) | Kermanshah | 6-7 | NI | NI | NI | ||

| T | 196 | 69.3 | |||||

| M | 98 | 28.6 | |||||

| F | 98 | 71.4 | |||||

| Yazdanpanah et al. (15) | Kohgiloyeh and Boyerahmad | 5-7 | Recombivax - HB | 0 | NI | ||

| T | 729 | 84.4 | |||||

| M | 425 | 83.8 | |||||

| F | 304 | 85.2 | |||||

| Mahyar (16) | Qazvin | 6 | NI | NI | NI | ||

| T | 40 | 87.5 | |||||

| M | 20 | 89 | |||||

| F | 20 | 83 | |||||

| Rafizade et al.(17) | Zanjan | 7-9 | NI | NI | 3 (1) | ||

| T | 273 | 48 | |||||

| Mostafavi Zadeh (18) | Charmahal Bakhtiari | 5-6 | NI | NI | NI | ||

| T | 394 | 64 | |||||

| M | 211 | 61 | |||||

| F | 183 | 67.8 | |||||

| Esmaili et al.(19) | Mazandaran | < 7 | NI | NI | NI | ||

| T | 97 | 87.6 | |||||

| M | 52 | 86.54 | |||||

| F | 45 | 88.9 | |||||

| Jazayeri, (Unpublished) | Alborz | 9-15 | Heber biovac | 0 | 0 | ||

| T | 821 | 51.6 | |||||

| M | 423 | 53.2 | |||||

| F | 398 | 50 | |||||

| Shamsizadeh et al. (20) | Khoozestan | 6 | Cuban Vaccine | NI | NI | ||

| T | 427 | 75.4 | |||||

| M | 204 | 70.1 | |||||

| F | 223 | 80.3 | |||||

| Hosseini et al. (21) | Tehran | 1.5-5 | NI | 0 | |||

| T | 165 | 91 | |||||

| Salehi et al. (22) | Isfahan - Lorestan - Charmahal Bakhtiari | 5.5-6 | Recombivax | NI | NI | ||

| T | 3758 | 80.7 | |||||

| M | 2456 | 79.2 | |||||

| F | 1302 | 83.5 | |||||

| Ahmadi et al. (23) | Hormozgan | 12-15 mo, 21-24 mo | NI | NI | NI | ||

| T | 186 | 87 | |||||

| Kazemi et al. (24) | Zanjan | 1-4 | NI | 0 | 0 | ||

| T | 100 | 98 | |||||

| M | 58 | 97 | |||||

| F | 42 | 42 | |||||

| Azarkar (25) | Khorasan - Razavi | 12-16 mo | Eberbiovac | Khorasan - Razavi | 12-16 mo | ||

| T | 100 | 81 | |||||

| M | 50 | 80 | |||||

| F | 50 | 82 | |||||

| Dahifar (26) | NI | 15- 45 mo | Herberbiovac | NI | 0 | ||

| T | 538 | 84.4 | |||||

| M | 294 | 82 | |||||

| F | 244 | 87.5 | |||||

| Jafarzadeh et al. (27) | Kerman | Neonate | Herberbiovac | 3 (1.29) | 6 (2.59) | ||

| T | 231 | 96.1 | |||||

| M | 113 | 94.7 | |||||

| F | 118 | 97.5 | |||||

| Fatolah Poor et al. (28) | Kordistan | 1-2 | NI | NI | NI | ||

| T | 225 | 93.3 | |||||

| M | 121 | 93.3 | |||||

| F | 104 | 93.2 | |||||

| Salehi et al. (29) | Sistan Baloochestan | 15-23 mo | Herberbiovac | NI | NI | ||

| T | 324 | 78.4 | |||||

| M | 174 | 77 | |||||

| F | 150 | 80 | |||||

| Jafarzadeh et al. (27) | West Azerbayjan | Neonate | Herberbiovac | Neg | Neg | ||

| T | 290 | 98.3 | |||||

| M | 145 | 98.6 | |||||

| F | 145 | 97.9 | |||||

| Moradi (30) | Golestan | 7-12 mo | Euvax B, a Korean HBV vaccine | 1 (4.6) | 5 (2.2) | ||

| T | 215 | 86 | |||||

| M | 119 | 84 | |||||

| F | 96 | 89.9 | |||||

| Zamani et al. (31) | Tehran | 12-24 mo | Heber Biotec, | NI | NI | ||

| T | 115 | 94.8 | |||||

| M | 62 | 93.5 | |||||

| F | 53 | 96.2 | |||||

| Shokri et al. (32) | Kerman | Neonate | Heberbiovac | NI | NI | ||

| T | 735 | 95.2 | |||||

| M | 357 | 94.1 | |||||

| F | 378 | 96.2 | |||||

| Rostami et al. (33) | Mazandaran | 15 mo | Heber biovac | NI | NI | ||

| T | 97 | 85.6 | |||||

| M | 50 | 88 | |||||

| F | 47 | 83 | |||||

| Rezaei et al. (34) | Semnan | 1-15 | Cuban Vaccine | NI | NI | ||

| T | 210 | 79 | |||||

| M | 105 | 78 | |||||

| F | 105 | 80 |

a Data are presented as % for ≥ 10

b T: total; M: male; F: female

| Prevalence | Coefficient | Standard Error | CI 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 0.0196224 | 0.056 | -0.0005681 - 0.0398129 |

| Mean age | -0.0457975 | 0.001 | -.0682583 - (-.00233366) |

| Type of vaccine | -0.0509606 | 0.162 | -0.1261901 - 0.0242688 |

| Constant | -38.23503 | 0.060 | -78.49684 - 2.026786 |

| Variables | Number of Study | Prevalence, % | CI 95% | Mode | I Square | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 28 | 80 | 0.76-0.83 | Random effect | 99.8 | < 0.001 |

| Male | 24 | 80 | 0.77-0.84 | Random effect | 99.7 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 24 | 83 | 081-0.86 | Random effect | 99.6 | < 0.001 |

| Author(s) | Country | Number | Age, y | No Responder, % | Responder, % | Association With Age | Association With Gender | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elian et al. (35) | Palestine | 180 | 2 - 11 | 1.7 | 98.3 | Yes | No | ≤ 0.04 |

| Livramentoet al. (36) | Brazil | 371 | 10 - 15 b | 50.1 | 49.9 | NI | NI | NI |

| Madour et al. (37) | Libya | 277 | 1 - 12 | 32.1 | 67.9 | Yes | No | 0.386 |

| Zanettiet al. (38) | Italy | 1212 | 10.9 c | 36 | 64 | NI | No | 0.0001 |

| Dong (39) | China | 5407 | 0 - 8 | 35.46 | 64.54 | Yes | NI | < 0.05 |

| Sallamet al. (40) | Yemen | 170 | 13 - 73 mo | 16.5 | 83.5 | No | NI | 0.4 |

| Belloniet al. (41) | Italy | 1968 | 38 wk | 2.5 | 97.5 | NI | NI | < 0.05 |

| Hwanget al. (42) | China | 100 | NI | 10 | 90 | Yes | NI | NI |

| Chongsrisawatet al. (43) | Thailand | 2887 | 0.5 - 18 | 58.4 | 41.6 | NI | NI | NI |

| Sadeck et al. (44) | Brazil | 56 | 6 - 12 mo | 3.7 | 96.3 | NI | NI | > 0.05 |

| Aypak et al. (45) | Turkey | 530 | 2 - 12 | 33.6 | 66.4 | Yes | No | 0.000 |

| Liao et al. (46) | China | 966 | 0.5 - 15 | 11 | 89% | Yes | No | < 0.09 |

a Abbreviations: NI: Non identified.

b Mean age is equal to 12.5.

c Data are presented as mean age.

4. Discussion

HBV Expanded program on immunization was started in Iran in 1993. Accordingly, more than 98% of infants have been vaccinated so far. There are ample data on the vaccine coverage rate, response to the vaccine, amnestic response to booster doses etc. among Iranian healthy children. However, no systematic review evaluated the levels of responsiveness to HBV vaccine. Moreover, most of those articles published in Persian language, makes the interpretation of data more incomprehensible. In this review, the impacts of different variables including age, gender, type of vaccine etc. on the rate of responsiveness were assessed statistically.

Of 11639 children-studied, 9311 (80%) and 2328 (20%) were responders and nonresponders to vaccine, respectively. There have been numerous published data on the rate of response to HBV vaccine internationally; the reported rate of HBV vaccine responsiveness ranged between 41.6 and 98.3% (Table 4). The reverse was also realistic for the extreme of no responsiveness to vaccine. In Iran, the rate of responders to vaccine was between 47.6 and 98.3%; however, in most studies (24 out of 28 papers, 85.7%), responders were above 69% of population in the surveys.

Regarding the impact of age on the rate of response to vaccine, we did not find a significant difference between subjects, despite finding cut-off levels for anti-HBs between 500.95 and 164.82 IU/mL for those who were under three years old versus children more than three years old, respectively. However, this finding did not reach significance statistically. There are considerable variations between studies for association between the age of participants and response to vaccine. The massive gaps between the extreme of these results substantially correlated to the age of vaccines. For example, Table 4 shows that more increase in the age of vaccines, the more decline in the rate of responders. The other important issue is the timing between the last dose of vaccine administration and measurement of anti-HBs. Globally, in various reports, the age of children ranged between 5 and 15 years old; which makes substantial variance between the levels of anti-HBs in different age groups. On the other hand, this review and other studies showed that with increase in age, the number of nonresponders to vaccine increased significantly. Versatile ethnic groups, geographic variations, different age groups between subjects and difference in the endemicity of HBV in those areas might be the reasons for such discrepancies.

What is the impact of low level of anti-HBs on acquisition of HBV infection? Taken together, with exception of some rare reports on healthcare workers who were nonresponders to vaccine and subsequently infected with HBV (47-49), there is no data to support that after robust rising in anti-HBs following HBV vaccination, subsequent decrease in anti-HBs levels endanger the subject to HBV infection (50). Previous results showed that memory T cells maintain the response to the virus after encountering. This issue has been highlighted by the fact that after booster dose(s) of HBV vaccine in hypo/nonresponders, there has been amnestic response manifested by increase in the levels of anti-HBs (45, 51).

Interestingly, between years 1995 and 2014, there was no significant difference in the mean anti-HBs titers between Iranian studies (P = 0.428). This finding together with this issue that the type of vaccine used did not show any significant differences between the rate of response to vaccine (P > 0.05), indicate the reasonable potency and antigenicity of vaccine used in Iranian EPI, which were already assessed by our lab in vivo and in vitro studies (52, 53).

Despite some studies showed some differences in response to HBV vaccine between rural and urban areas (54-57), we did not find any significant difference in Iranian publications. Furthermore, in our own yet unpublished study on 1200 samples from two categories of rural and urban districts, we did not find any considerable changes (Jazayeri’s unpublished manuscript).

Overall, Iranian surveys did not find any significant correlation between gender of participants and the rate of response to vaccine (P = 0.119), which was similar to other findings (Table 4).

Three studies evaluated HBsAg in children; the rate was between 0 and 1.29%. Iran is considered as an intermediate area for HBsAg prevalence (2.54%) (58). On the other hand, the rate of past HBV infection, manifested by anti-HBc, ranged between 0 and 7.7% in this review. Both relative high prevalence for HBsAg (4.6%) and anti-HBc (7.7%) were reported exceptionally from Golestan and Kerman provinces. Previous reports showed rates of 6.3% HBsAg and 8% anti-HBc in general population in these areas, respectively (59, 60). However, our unpublished data on 821 samples from vaccinated children showed no positive cases for both two markers (Jazayeri and Alavian, unpublished). Altogether, 0 to 1.29% prevalence of HBsAg together with 0 to 2.5% anti-HBc from different provinces underscored the usefulness of HBV vaccination for substantial reduction in HBV endemicity in Iran.

The results arose from this review highlighted special topics. First, in Iran, the vaccine was safe without considerable consequences. Second, the vaccine was effective in stimulating the immune response of vaccines reasonably, despite being different in generation, manufacturers and types. Third, there was no substantial difference between Iranian and other international investigations in the rate of nonresponsiveness to HBV vaccine.