1. Background

Chronic viral hepatitis B (CVHB) remains a common health problem throughout the world. In recent years, due to increased information about the transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and the application of precautions, such as routine HBV vaccination programs, HBV prevalence has been declining (1, 2). However, with increasing life expectancy, the use of antiviral medications is prolonged and therefore drug resistance is increasing. This is an emerging problem in the field of chronic liver disease.

Liver biopsy is still necessary for predicting underlying HBV-related liver injury and for deciding whether to initiate antiviral medication (3). Liver biopsy is an invasive procedure with certain risks, which forces investigators to focus on non-invasive methods to replace percutaneous biopsy (4). Assessing liver stiffness with ultrasound and measuring serum biomarkers are inadequate for determining the severity of liver fibrosis or for grading the inflammatory process in the liver.

The programmed cell death of apoptosis is a protective mechanism in infected hepatocytes, not only to prevent spread of the virus to other hepatocytes and to control viral replication (5), but also to decrease pro-inflammatory cytokine release from injured hepatocytes (6). Upregulation of apoptosis has been shown to have a critical role in inducing inflammation and fibrogenesis in the liver. The amount of cytokeratin-18 fragments cleaved by caspases during apoptosis seems to be a good marker of apoptosis (7), and can easily be measured with a sandwich ELISA technique (M30-based ELISA) (8). M30 determines the degree of apoptotic cells in epithelial organs and tissues. Serum M30 levels were higher in chronic HBV patients compared to healthy controls, and M30 levels were able to be used to discriminate mild from advanced liver fibrosis (9, 10). In addition, Giannousis et al. showed a decrease in serum M30 levels after six months of antiviral therapy (11).

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the utility of serum M30 levels in predicting the hepatic fibrosis stage in CVHB patients.

3. Methods

Forty patients admitted to our clinic between January and December 2011, who underwent liver biopsy with a diagnosis of CHB, were included in this cross-sectional study. The inclusion criterion was age over 18 years. The exclusion criteria were co-infection with hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), alcohol abuse (40 g/day for men and 20 g/day for women), biopsy-proven non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, or any immunological liver disease. The decision to perform liver biopsy was based on the EASL HBV guidelines (3). Approval for the study was granted by the local clinical research ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from each patient.

The baseline characteristics of the patients and their laboratory results, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), platelet count, and HBV DNA, were collected from the computerized hospital database. Blood samples were obtained from the patients after informed consent on the same day as the liver biopsy, and were stored at -80°C until the procedure was completed. M30 values were measured using an M30 ELISA kit (Peviva; Bromma, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

The severity of fibrosis was assessed as mild (F0 and F1), moderate (F2 and F3), or advanced (F4 and F5), and the histological activity index (HAI) was classified as mild (1 - 5), moderate (6 - 8), or severe (9 - 12).

Forty healthy controls were also included in the study for comparison with the patient group’s laboratory parameters, including M30, ALT, AST, and platelet count. All of the controls completed a questionnaire to determine whether they had any chronic illness that could affect the results, and digital data from our hospital were used to evaluate the presence of chronic hepatitis and possible etiologic factors, such as viral hepatitis or HIV.

The statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS software version 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Baseline demographic values were calculated with the Kruskal-Wallis test, then the post-hoc test was performed. The continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD), or minimum (min) and maximum (max) for certain categorized values. Correlation analyses were done with Pearson’s correlation test. P values of < 0.05 were accepted as statistically significant.

4. Results

Twenty-five (52%) of the CVHB patients were male, and their mean age was 45.7 years, which were both higher than in the controls (Table 1). Five of these patients (10%) were HBeAg-positive and the remainder were negative. Baseline laboratory evaluations revealed that the CVHB patients had higher ALT, AST, and M30 levels and lower platelet counts compared to the controls.

| Control Group (n = 40) | Patient Group (n = 48) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (min - max) | 39.7 (20 - 79) | 45.7 (20 - 71) | 0.003 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 14 | 25 | |

| Female | 26 | 23 | 0.041 |

| ALT, U/L (min - max) | 18.4 (7 - 46) | 57.0 (10 - 401) | < 0.001 |

| AST, U/L (min - max) | 19.5 (8 - 36) | 42.7 (6 - 255) | < 0.001 |

| Platelets/mm3 (min - max) | 252.5 (149-366) | 193.574 (28.000-455.000) | < 0.001 |

| M30, U/L (min - max) | 135.6 (79.2-254.2) | 154.1 (92.84-278.9) | 0.017 |

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics of CHBV Patients and Healthy Controls

Mean age, duration of disease, and platelet count did not differ according to the severity of liver fibrosis (Table 2). M30 levels were also similar in each group. However, AST and ALT levels were prominently increased in the moderate group compared to the mild fibrosis group. In contrast, HBV DNA levels decreased as the severity of fibrosis increased (P = 0.007).

| Severity of Fibrosis | Mild (n = 21) | Moderate (n = 26) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (min - max) | 43.8 (25 - 60) | 47.0 (20 - 71) | 0.298 |

| Duration of disease, y, mean (min - max) | 4.8 (1 - 16) | 7.1 (1 - 23) | 0.518 |

| HBV DNA, U/L, mean (min - max) | 974,530 (2,690 - 18,900,000) | 12,930,000 (2,756 - 59,800,000) | 0.007 |

| ALT, U/L, mean (min - max) | 33.7 (15 - 121) | 75.0 (10 - 401) | 0.019 |

| AST, U/L, mean (min - max) | 27.1 (15 - 72) | 54.1 (6 - 255) | 0.006 |

| Platelets/mm3, mean (min - max) | 191,950 (28,000 -362,000) | 193,850 (111,000 - 455,000) | 0.470 |

| M30, U/L, mean (min - max) | 149,600 (92.8 -278.9) | 157,900 (93.4 - 261.1) | 0.811 |

Comparison of M30 Levels and Other Parameters According to Severity of Liver Fibrosis

Transaminase level, HBV DNA level, platelet count, mean age, and duration of disease were all similar among the groups (Table 3). M30 levels were also the same in each group in terms of HAI.

| Severity of HAI | Mild (n = 20) | Moderate (n = 23) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (min.–max.) | 45.9 (25 - 71) | 45.5 (20,66) | 0.713 |

| Duration of disease, y, mean (min - max) | 6.1 (1 - 16) | 5.2 (1 - 11) | 0.386 |

| HBV DNA, U/L, mean (min - max) | 20,000,000 (2,756 - 59,800,000) | 1,214,114 (2,690 - 15,800,000) | 0.072 |

| ALT, U/L, mean (min - max) | 49.5 (15 - 121) | 52.0 (10 - 178) | 0.200 |

| AST, U/L, mean (min - max) | 35.7 (6 - 72) | 39.7 (15 - 97) | 0.059 |

| Platelets/mm3 mean (min - max) | 187,900 (28,000 - 255,000) | 203,340 (114,000 - 455,000) | 0.715 |

| M30, U/L, mean (min - max) | 159.5 (103.7 - 278.9) | 149.6 (92.8 - 246.4) | 0.674 |

Comparison of M30 Levels and Other Parameters According to Degree of HAI in the Liver

The correlation analysis revealed a weak correlation between M30 and HBV DNA levels (r = 0.354, P = 0.013), but no correlation was observed among ALT and AST values (r = 0.270, P = 061 and r = 0.244, P = 0.92; respectively).

5. Discussion

The main target of antiviral medication therapy against HBV is the prevention of HBV-related morbidities, which are mainly liver insufficiency and hepatocellular carcinoma (3). Since recent studies have shown a correlation between HBV DNA and HBV-associated disorders, monitoring the HBV DNA load has become a crucial part of HBV therapy. However, apart from monitoring the HBV DNA viral load and transaminase levels, there are no other serological markers for predicting the severity of ongoing inflammatory or fibrotic processes. However, some studies of non-invasive markers for predicting the severity of liver fibrosis are available in the medical literature (12-15). Unfortunately, none of these parameters reflect the real status of the liver, which is only possible with liver biopsy.

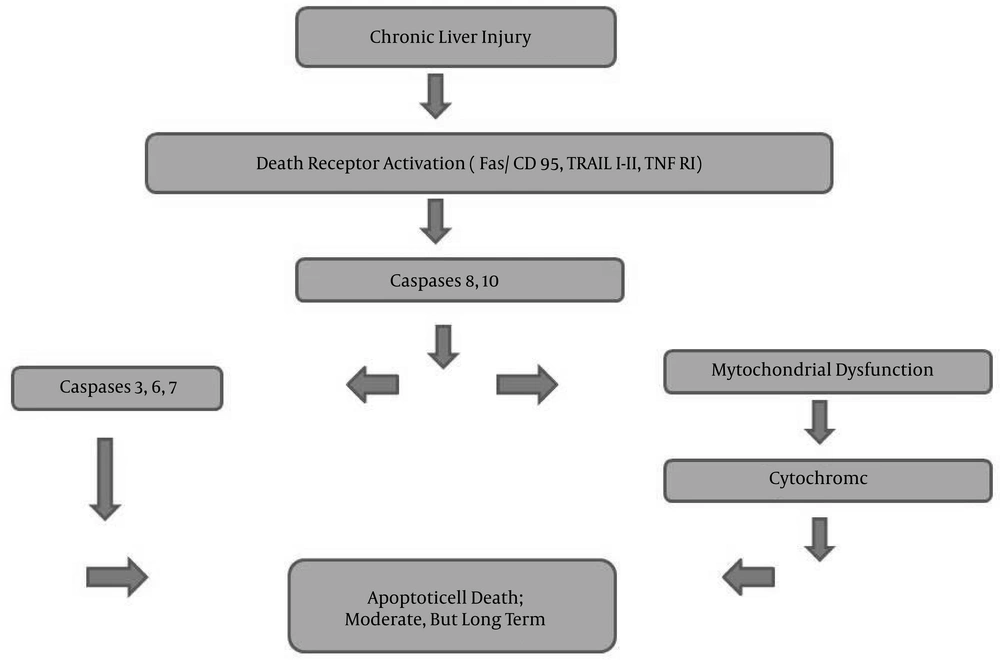

Apoptosis, programmed cell death, is crucial when it becomes dysregulated in chronic hepatitis, such as in viral hepatitis, alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, cholestatic processes, and Wilson’s disease (16-19). The increase of apoptotic cells results in cytokine secretion, leading to induction of inflammatory and fibrotic processes (Figure 1) (6). Downstream from the cell-death receptor, the proteolytic cascade leads to activation of caspases 3, 6, and 7 (16, 20). The activation of caspases may be related to mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to cytochrome c release or direct cleavage (20, 21). The susceptibility to apoptotic cell death may depend on the HBV genotype, as well (22). Not only apoptotic cell death, but also autophagic cell death, may be good predictors for defining the level of liver injury at the beginning of treatment and during the follow-up period (23).

Similar to our results, M30 levels in the healthy population were found to be lower than in CHB patients (6, 10, 18, 23). As expected, Eren et al. found similar M30 values in healthy controls and inactive CHB carriers (10). Higher M30 values in CHB patients compared to healthy individuals is understandable, due to ongoing liver inflammation.

Serum M30 levels were found to be significantly higher in chronic HBV patients compared to healthy subjects (10, 18, 23). Moreover, one study found that M30 values increased with increasing severity of liver fibrosis, and reached their highest level in cirrhotic patients (23). However, the role of apoptotic markers for replacing liver biopsy in CHB patients and the utility of M30 levels for distinguishing inactive CHB carriers from CHB patients are still controversial. Papatheodoridis et al. gave a cut-off value of 240 U/L for predicting CHB with 60% sensitivity and 100% specificity (9). Rather than grading liver inflammation, Joka et al. determined a cut-off value of 157.5 U/L for predicting mild fibrosis from significant fibrosis (≥ F2) in the liver (64% sensitivity and 61% specificity) (18). Differentiating ongoing high-inflammation processes and high fibrosis scores in the liver is crucial for the initiation of antiviral medication without requiring liver biopsy. Similar to Eren et al. and Joka et al., we were unable to identify any relationship between M30 values and the mild to moderate stages of liver fibrosis (10, 18).

This was a cross-sectional study performed during a specific time period. Therefore, we could not find a sufficient number HBV patients with advanced liver fibrosis. This was an important limitation of the current investigation.

The ALT-to-platelet ratio (the APRI index) and the FIB-4 scores, which are based on ALT, AST, platelet count, and age of the patient, have been widely investigated. Although there were some promising results, large-scale database studies revealed that the APRI index and FIB-4 scores may not be adequate for predicting the severity of underlying liver disease in HBV patients (24, 25). Our results support the idea that the APRI index and FIB-4 scores are not correlated with the severity of liver fibrosis (unpublished data).

In conclusion, although M30 levels were higher in CVHB patients than in healthy controls, our results do not support the use of M30 levels for predicting the severity of underlying fibrotic or inflammatory processes in CHB patients. Further studies are necessary in order to clarify the role of apoptotic mechanisms in hepatic injury due to HBV, and to establish the utility of M30 in replacing liver biopsy.