1. Context

The chronic hepatitis B (CHB) virus, which is a major cause of acute and chronic morbidity and mortality, affects approximately 240 million people worldwide (1). Individuals with CHB infection have a significantly increased risk of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and decompensated liver disease (2, 3). It is now clear that active hepatitis B virus (HBV) replication is the key driver of liver injury and disease progression. Thus, antiviral treatment, which suppresses HBV DNA replication to the lowest possible level, is the only option to prevent the development of HCC in CHB patients (4). Epidemiological studies showed that patients treated with antidrugs therapy achieved hepatitis B surface antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion and had a reduced risk of cirrhosis and HCC compared to those who did not receive such therapy (5, 6).

The current antiviral therapeutic options for CHB patients include interferon (IFN) and oral nucleotide analogs. IFN therapy, including conventional IFN and pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN), has direct antiviral activity and immune-stimulatory properties. Thus, it has been widely used in the past decade. Studies have shown that patients who accepted IFN therapy had a lower hazard of decompensated liver diseases (5, 6). However, the existing clinical data suggests that the antiviral effect of IFN therapy is not satisfactory at present. The efficiency of IFN therapy is only accounts for 30% - 40% in clinical observation ,and 60% - 70% patients had no response for patients with active liver inflammatory (7, 8). Therefore, it is important to identify the factors that may affect the treatment outcomes of CHB patients who receive IFN.

Epidemiological studies have suggested that both viral and host factors could markedly influence the outcome of antiviral therapy (9). In recent years, host-genetic factors have been implicated in the antiviral treatment efficacy of various diseases, such as hepatitis B and hepatitis C. A genome-wide association study revealed that polymorphisms (rs12979860, rs8099917, and rs12980275) of the IFNL3 gene were associated with the efficacy of anti-HCV treatment and natural clearance of HCV (10-12). Although the mechanism remains largely unknown, similar associations have been observed in the antiviral treatment of CHB. Sonneveld et al. and Lampertico et al. reported that polymorphisms were predictors of the serological response to IFN (13, 14), but conflicting results have been reported (15, 16).

A previous meta-analysis of the limited published data was performed (17). However, it failed to consider that the pooled ORs could clarify the role of these polymorphisms in the antiviral response of CHB patients. Herein, to clarify the relationship between IFNL3 polymorphisms (rs12979860, rs8099917, and rs12980275) and the response of CHB patients to IFN therapy, we performed a comprehensive meta-analysis based on updated evidence.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

A literature search of the EMBASE and PUBMED/MEDLINE databases for all relevant English articles was performed from January 2009 to March 2015 using the keyword “IFN lambda 3” or “IFNL3,” combined with the following terms: “ IFN therapy,” “ hepatitis B,” and “polymorphisms.” The reference lists of the selected articles were also scanned to retrieve relevant articles. The search was limited to studies on humans.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (i) studies related to the association between IFNL3 polymorphisms (including rs12979860, rs8099917 and rs12980275) and the response of CHB patients to IFN therapy or IFN mixed with nucleotide analogs; (ii) the diagnosis of CHB was based on a seropositive result, with HBsA) positivity for at least 6 months; (iii) the end point was defined as a response to IFN therapy; and (iv) the studies provided enough information for calculation of odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) or adjusted ORs and 95% CIs. The following studies were excluded: (i) neither IFNL3 genotypes data nor response data to the treatment was provided; (ii) patients coinfected with the HCV, hepatitis delta virus, or human immunodeficiency virus; (iii) patients WHO received immunosuppressants, chemotherapy, or systemic corticosteroids during the study period; and (iv) patients who did not meet the diagnostic criteria.

2.2. Data Extraction

After initial screening of the full-text articles, two investigators extracted all the data independently, using a standardized form. For each study, the following data were extracted: first author’s surname, publication year, country where the study was conducted, ethnicity, number of patients, gender ratio, average age of the patients, antiviral therapy, sample size of genotyped response and nonresponse, genotyping methods, and genotyping results.

2.3. Quality Assessment

A quality assessment was undertaken by using a customized version of the STROBE checklist for case-control studies (18). The STROBE checklist provides recommendations on the reporting of observational research. Items in the checklist relate to the title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and other sections of articles providing best-practice guidelines. Studies that scored above 13 points on the checklist were considered to have adequate internal validity for a quantitative meta-analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A response was defined as HBeAg seroclearance or virus DNA load suppression after treatment, otherwise treated as a nonresponse. STATA 13.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) software was used for the statistical analysis. As some studies did not supply enough information to calculate the OR of genetic models other than the dominant model, we extracted the OR for the dominant model from all the publications. The dominant model was used to assess the relationship between the IFNL3 polymorphisms and response rate in CHB patients in the meta-analysis, with the effect estimates of the ORs and their corresponding 95% CIs. The response rate was assumed to increase when the OR value was more than 1.

The heterogeneity between studies was tested by means of the Q-statistic test and I2 statistics. In cases of significant heterogeneity (P < 0.1 or I2 > 50%), the random-effects model was applied to assess the effect of the IFNL3 polymorphisms on the therapeutic response of the CHB patients. Otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used (P > 0.1 and I2 < 50%). To test the sources of heterogeneity among the studies, subgroup analyses were carried out by antiviral therapy (IFN and mixed), age (young: less than 35 years; elder: older than 35 years), sample size (small: less than 200; large sample: more than 200), gender ratio (small: less than 2.57, large: greater than 2.57), genotyping methods (MassArray and non-MassArray). A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the stability of the results. Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analysis of rs12980275 could not be conducted due to a limited number of studies. A visual inspection of asymmetry in funnel plots was conducted only for rs12979860. In addition, Egger’s tests were performed to examine publication bias.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

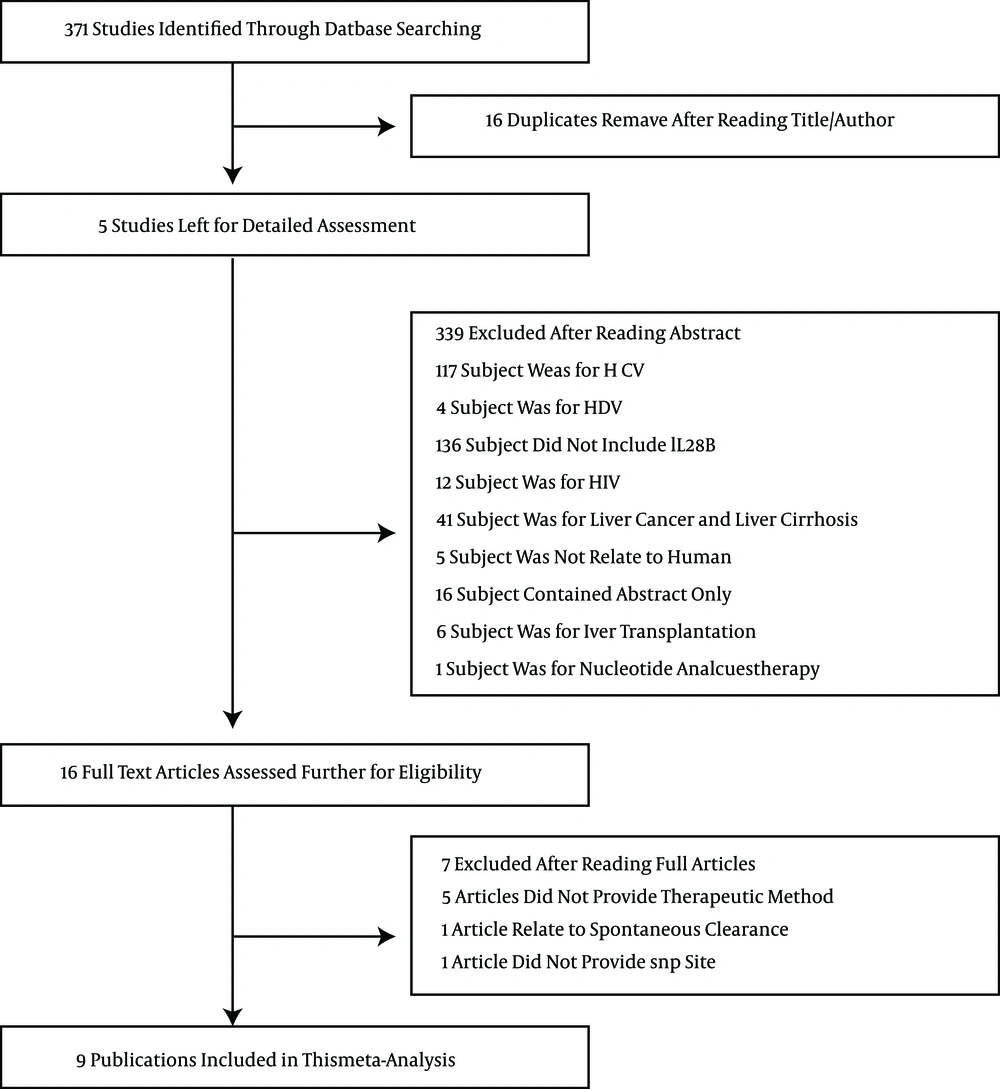

The database search identified 371 studies. The details of the selection process are outlined in Figure 1. Of the 371 studies, nine studies were included in the meta-analysis. Among these nine studies, seven studies (n = 975) focused on rs12979860, five studies (n = 1111) focused on rs8099917, and three studies (n = 607) focused on rs12980275.

Information on the included studies is presented in Table 1. Five of the studies included Asians, and four studies focused on other races. The IFN therapy in the studies included IFN, PEG-IFN, and PEG-IFN mixed with nucleotide analogs. The scores of the quality assessment are also presented in Table 1.

| Study | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Response/ Nonresponse | Males/ Females | Mean Age | Genotyping Methods | Antiviral Therapya | Genotyping | Quality Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP 1 | SNP 2 | SNP 3 | |||||||||||

| Tseng et al. (15) | 2011 | China | Asian | 115 | 94/21 | 84/31 | 35.90 | TaqMan | IFN | N | Y | N | 15.0 |

| Chen et al. (19) | 2011 | China | Asian | 82 | 38/44 | 59/23 | 29.13 | PCR-RLFP | IFN | Y | Y | N | 13.5 |

| Sonneveld M et al.(13) | 2012 | Netherlands | Mixed | 205 | 90/115 | 149/56 | 35.00 | TaqMan | IFN | Y | N | Y | 16.5 |

| Wu X et al. (20) | 2012 | China | Asian | 512 | 162/350 | 381/131 | 31.60 | MassArray | IFN and NAS | N | Y | N | 18.5 |

| Holmes J et al. (21) | 2012 | Australia | Asian | 96 | 38/58 | 69/27 | 34.20 | TaqMan | IFN | Y | N | N | 14.5 |

| Niet A et al. (16) | 2012 | Netherlands | Mixed | 95 | 37/58 | NA | NA | Illumina | IFN and Adefovir | Y | N | N | 14.0 |

| Boglione L et al. (22) | 2014 | Italy | Mixed | 190 | 89/101 | 134/56 | 41.50b | TaqMan | IFN | Y | Y | Y | 19.5 |

| Zhang Q et al. (23) | 2014 | France | Caucasian | 97c | 53/42 | 85/12 | 36.00b | TaqMan | IFN | Y | N | N | 17.5 |

| Wu H et al. (24) | 2015 | China | Asian | 212 | 74/138 | 153/59 | 31.40 | MassArray | IFN | Y | Y | Y | 15.0 |

Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis

3.2. Meta-Analysis

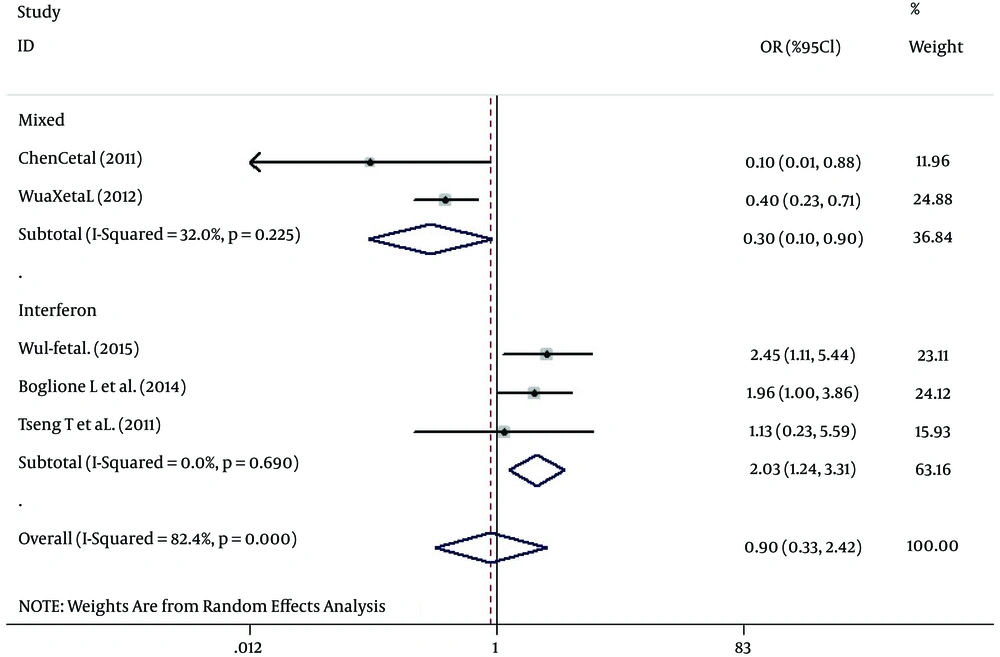

In the pooled analysis, there was a significant association between the rs12980275 polymorphism and the response of CHB patients to antiviral therapy in the random-effects model (OR = 2.85, 95% CI = 1.14 - 4.56; P for heterogeneity = 0.106). However, no significance was found for the rs12979860 (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.35 - 1.14; P for heterogeneity = 0.152) and rs8099917 (OR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.29 - 1.80; P for heterogeneity of < 0.001) (Table 2). To detect the sources of between-study heterogeneity for rs8099917, subgroup analyses were performed. When stratified by antiviral therapy, the IFN treatment group showed a significantly increased response (OR = 2.03, 95% CI = 1.24 - 3.31, P for heterogeneity = 0.690), but the mixed treatment group did not (OR = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.10 - 0.90, P for heterogeneity = 0.225; Figure 2). However, no significance was presented in the other subgroups (Supplementary Forest Plots S1 - S4). Similar results were also found for rs12979860 in the subgroup analyses (Supplementary Forest Plots S5-S7).

| Study ID | With a Response | Without Response | OR (95% CI) | Pooled OR (95% CI) | Q | P for Heterogeneity | I2 (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hom | Het | Hom | Het | ||||||

| rs12979860 (C/T)a | 0.74 (0.35 - 1.14) | 9.41 | 0.152 | 36.20 | |||||

| Chen C et al (19) | 32 | 6 | 42 | 2 | 0.25 (0.05 - 1.34) | ||||

| Sonneveld M et al. (13) | - | - | - | - | 2.89 (1.15 - 7.80)b | ||||

| Holmes J et al. (21) | 31 | 7 | 49 | 9 | 0.81 (0.28–2.41) | ||||

| Niet A et al. (16) | 20 | 17 | 36 | 22 | 0.72 (0.31-1.66) | ||||

| Boglione L et al. (22) | 69 | 20 | 21 | 80 | 4.29 (1.59 - 11.58)b | ||||

| Zhang Q et al. (23) | 23 | 19 | 24 | 29 | 1.46 (0.65 - 3.30) | ||||

| Wu H et al. (24) | 64 | 10 | 101 | 37 | 2.35 (1.09 - 5.04) | ||||

| rs8099917 (T/G)c | 0.90 (0.33 - 2.42) | 22.72 | < 0.001 | 82.40 | |||||

| Tseng T et al. (15) | 19 | 2 | 84 | 10 | 1.13 (0.23 - 5.59) | ||||

| Chen C et al. (19) | 31 | 7 | 43 | 1 | 0.10 (0.01 - 0.88) | ||||

| Wu X et al. (20) | 135 | 27 | 324 | 26 | 0.40 (0.23 - 0.71) | ||||

| Boglione L et al. (22) | 72 | 17 | 69 | 32 | 1.96 (1.00 - 3.86) | ||||

| Wu H et al. (24) | 65 | 9 | 103 | 35 | 2.45 (1.11 - 5.44) | ||||

| rs12980275 (A/G)d | 2.85 (1.14 - 4.56) | 4.49 | 0.106 | 55.40 | |||||

| Sonneveld M et al. (13) | - | - | - | - | 3.16 (1.26 - 8.52)b | ||||

| Boglione L et al. (22) | 69 | 20 | 21 | 80 | 13.14 (6.58 - 26.25) | ||||

| Wu H et al. (24) | 64 | 10 | 101 | 37 | 2.35 (1.09 - 5.40) | ||||

Association Between the Three SNPs and Response to Therapy in CHB Under the Dominant Model

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis and Publication Bias

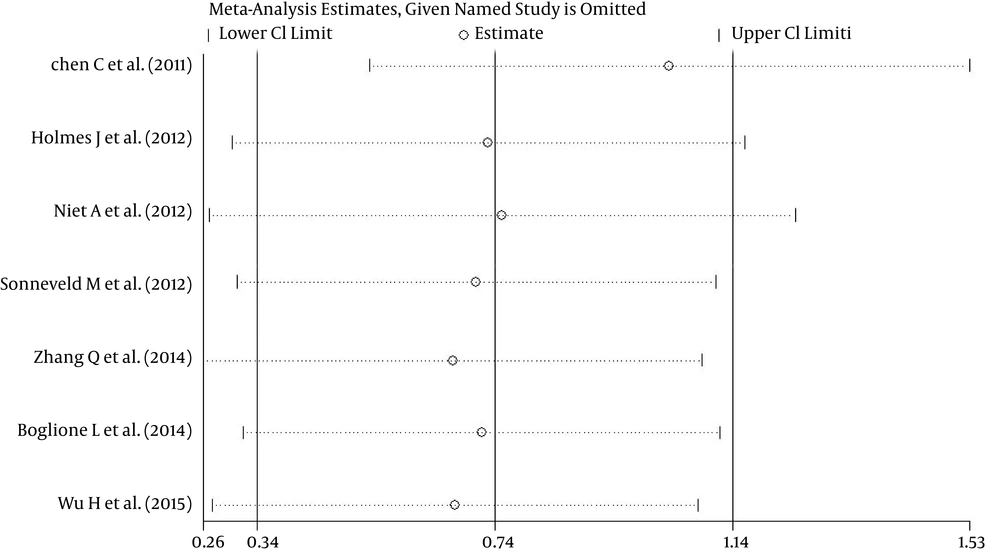

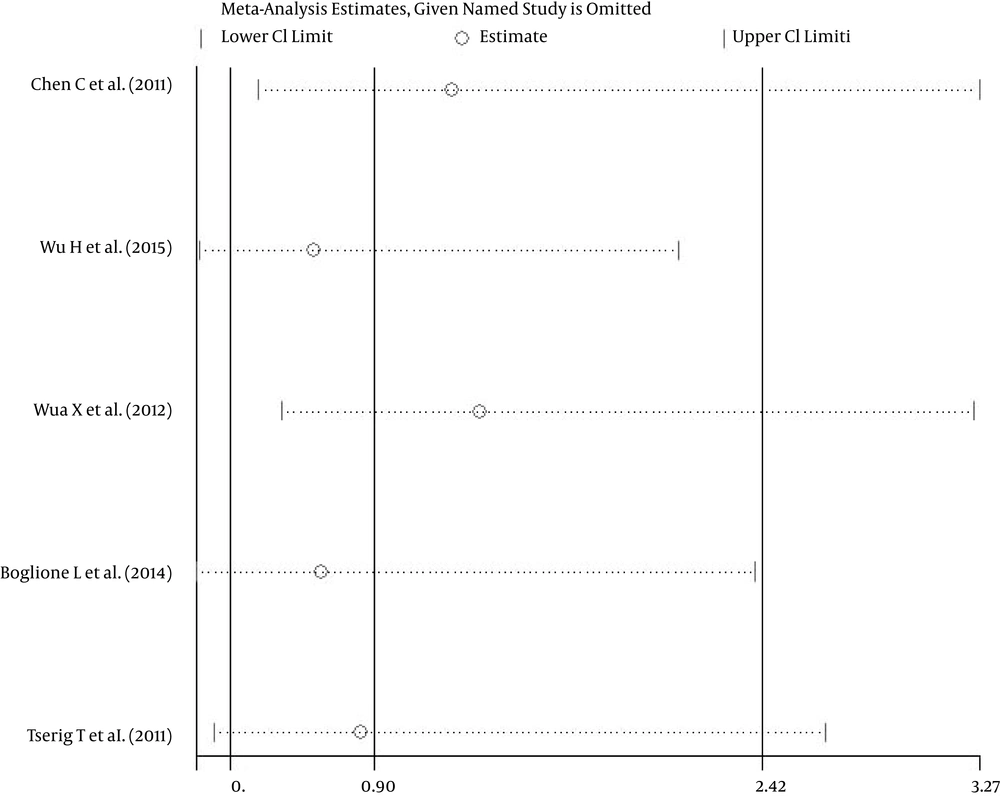

A single study included in the meta-analysis was deleted each time to reflect the influence of the individual effects of rs12979860 and rs8099917 on the pooled ORs. The results were not materially altered, indicating that they were statistically robust (Figures 3 and 4). Additionally, two adjusted OR values were used to pool for rs12979860 in the model. After excluding, the results of the analysis were stable (data not shown).

A funnel plot of rs12979860 was produced to assess publication bias. The shape of the funnel plot revealed no evidence of obvious asymmetry (supplementary funnel plot S8). This result was also supported by the Egger tests (P = 0.330 for rs12979860), indicating there was no statistical evidence of publication bias. Similar results were observed for rs8099917 in the Egger tests P = 0.661 for rs8099917).

4. Conclusions

As a prominent public health issue, the impact factors of CHB treatment have been studied on A genetic basis, and continuous efforts have been also made to unravel the factors. IFNL3, located in the chromosome 19q13 region, is a member of the type III IFN family (25, 26). It encodes a cytokine related to type I IFN and IFN-λ that activates a cascade via the JAK/STAT pathway, which enhances IFN-stimulating genes that are vital to control the HBV (25, 26). IFNL3 may also activate alternate antiviral pathways involved in the adaptive immune response, as supported by a study in which IFNL3, when used as a vaccine adjuvant, significantly decreased splenic regulatory T cells, increased splenic and peripheral blood CD8+ T cells, and enhanced T-cell functions (27).

Recently, a genetic variant, rs368234815, was found in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) with rs12979860 (28). The SNPs rs12979860 and rs12980275 were also in strong LD (r2 = 0.87), whereas rs12979860 and rs8099917, as well as rs12980275 and rs8099917, were not in LD (r2 = 0.43 and r2 = 0.46 (28). The study proved that rs368234815 polymorphism response to IFN therapy, the reason for its effect could be attributed to increasing expression levels of IFN-stimulating genes.

In this analysis, we pooled the studies on associations between rs12979860, rs8099917, and rs12980275 of the IFNL3 gene and the effect of IFN treatment on CHB patients. Roughly, a significant increase of possibility to response was observed for rs12980275 variant carriers, but no significant results were found for the rest of SNPs. However, when we examined the data by antiviral therapy subgroup, an active association was found in IFN subgroup for rs8099917, while negative association was found in the mixed group. This finding suggests that different antiviral therapies may play a crucial role in the treatment responses of CHB patients. The reason was likely to be attributable to different mechanisms, which the drugs rely on.

The main finding of this study was that the presence of the rs12980275 and rs8099917 polymorphisms predicted the treatment outcomes of CHB patients. The main reason for the insignificant result of rs12979860 may have been the lack of power to detect the very mild effects. According to some published studies, rs12979860 was a reliable predictor of IFN therapy outcomes in HBV (14, 29), whereas others suggested that this variant did not influence IFN-induced HBsAg clearance in patients with chronic HBV infection (30, 31). The results were inconsistent which might caused by different patients’ population the author chose.

The present study contains some limitations. First, the less included studies was eligible to analyze for rs12980275. Thus, there were insufficient numbers of studies to detect asymmetry in a funnel plot. Second, some of the original articles did not provide the specific genotype number of the SNP. Thus, the adjusted OR was used to pool the results. Hwever, the pooled ORs did not change in the sensitivity analysis when we excluded a single study at a time, indicating that the results of this meta-analysis were highly stable, and similar results were obtained using the funnel plot and Egger’s tests. Third, although the differences of treatment (IFN and mix) were existed, heterogeneity was reduced after the data were stratified by antiviral therapy. And the quality assessment was conducted to control quality of the included literature, which made the response group and nonresponse group treated under the mostly equal conditions in each study. Additionally, the results of this meta-analysis were relatively stable and credible according to the sensitivity analysis. Therefore, the heterogeneity of the treatment and treatment durations was thought as minimal when we were performing pool analysis. Finally, the studies included in our meta-analysis were limited to those that were published and found in databases, including PUBMED/MEDLINE and EMBASE.

Comprehensive studies are needed to identify gene-environment interactions involved in the treatment response of CHB patients. In addition, extended analyses are needed to delineate the functional mechanism underpinning the activity of the IFNL3 gene.

In summary, this study supports the idea that the IFNL3 gene is an important predictor of the response of CHB patients to IFN therapy.