1. Introduction

It has been estimated that about 350 million people in the world are chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV). This virus plays a significant role in liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Persistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for more than six months is an indicator of the development of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) (1).

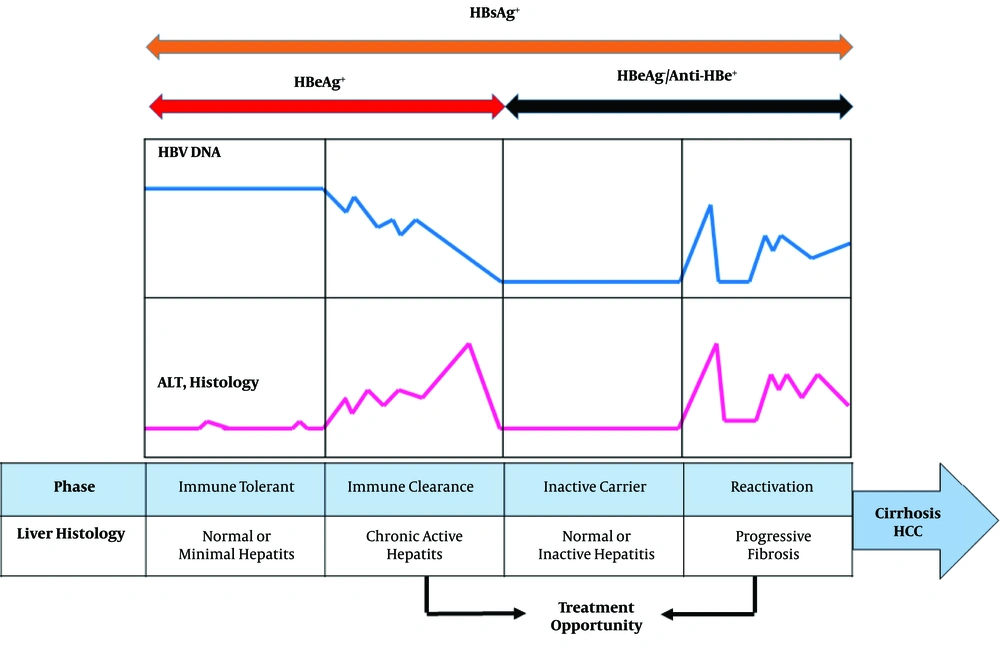

The natural history of CHB infection can be widely sub-divided into four phases including, immune tolerance (IT), immune clearance (or immune active [IA]), inactive HBsAg carrier (IC), and reactivation phase (Figure 1). High HBV DNA levels (> 20,000 IU/mL), presence of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), continual normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in the absence of active liver disease, and inflammation or fibrosis are indicators of IT phase of CHB infection. The IT phase occurs most frequently after perinatal transmission from HBsAg/HBeAg-positive mother. The immune tolerant phase can last from a few years to more than 30 years (2, 3). The IA phase is characterized by HBeAg positivity, elevated HBV DNA levels (above at least 2000 IU/mL), elevated ALT levels, active liver necroinflammation, and varying degrees of fibrosis. A consequence of this phase is HBeAg seroconversion and appearance of anti-HBe (4). The majority of patients subsequently enter the inactive HBsAg carrier state after HBeAg seroconversion. Low HBV DNA, repetitive normal ALT values, and slight hepatic necroinflammation are associated with the IC phase. However, some of the IC patients continue to show active liver disease and detectable serum HBV DNA, defined as HBeAg negative reactivation phase that can progress to liver cirrhosis (4). Based on viral factors, different HBV genotypes have been indicated to be a key factor in the clinical history of CHB infection. In addition, HBV basal core promoter (BCP) and precore/core mutation strains may increase more significantly in IA phase than IT phase (5).

The role of immune responses in the discrimination between different clinical states of CHB infection has remained to be unclear (6, 7). When the immune response against viral antigens is more intensive, histological damage and progressive fibrosis are greater (8). Generally, HBV specific T lymphocytes have shown to be key players in inducing liver injury during CHB infection (9). However, studies have indicated that T-cells often display inefficient T-cell response and could be a factor in IT phase (10, 11). Using the experimental animal model, microarray data analysis indicated that HBV, early in infection, does not regulate host cellular gene expression in the liver of infected animals (12). Differences in the host genetic factors and deregulation of gene expression may affect the natural history of viral hepatitis B and C (13, 14). During HBV chronic infection, viral proteins could negatively regulate immune responses by interfering with toll-like receptor (TLR), expression interferon (IFN) response, and signaling pathways (6, 15, 16). However, the mechanism behind these different phases of CHB infection remains a matter of debate. Also, there has been no high-throughput investigation on the relationship between HBV and hepatocytes modulating host gene expression. A potential approach for the study of molecular processes involved in HBV-related chronic infection is to leverage genome-wide technologies such as microarray gene expression for uncovering deregulated genes in different phases of the infection. In our previous study, we applied a network-based approach to investigate the role of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in the hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) oncogenesis using topological analysis of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks. Our results indicated that some important genes and microRNAs were involved in the progression of HCC patients (14).

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to identify candidate disease-associated genes and significantly altered biological processes for different phases of CHB infection (IT, IA, and IC phases) by integrated gene expression profiling and network analysis at a systematic level.

3. Methods

3.1. Microarray Data Collection

An Affymetrix microarray expression dataset (Accession number: GSE65359) containing 83 CHB patients was obtained from the Gene expression omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and further analyzed. This chip dataset included 22 IT, 50 IA, and 11 IC samples. The authors of this dataset have analyzed total RNA extracted from the liver biopsy of the IT, IA, and IC samples using GPL570 (HG-U133_Plus_2) Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array. The samples were used to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by the GEO2R web application. The GEO2R normalizes the data with log2 transformation (fold change [FC] of > 1) along with Benjamini and Hochberg (false discovery rate, [FDR]) and also represents the annotation information (17). We then obtained a list of upregulated and downregulated genes for each pair of consecutive phases (IT-IA and IA-IC). The DEGs were clustered using Hierarchical-clustering analysis based on the average linkage method. Treeview analysis of DEGs in different phases of CHB infection was performed and displayed by Treeview 1.1 software.

3.2. Functional and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

The database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery (DAVID), as a comprehensive set of functional annotation tool, was applied for gene ontology (GO) studies. In addition, Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) analyses, a database that contains a variety of cellular pathways, was applied for signaling pathways enrichment with a P value set at < 0.05 (18).

Additionally, to demonstrate the role of DEGs in signaling pathways, a focused signaling pathway enrichment of DEGs was performed by the Signaling pathway enrichment using the experimental datasets (SPEED). SPEED is a data collection and algorithm that identifies signaling pathways causing an observed regulatory pattern by comparing an input gene list against the signature genes using Fisher's exact test (19). Every significant hit in SPEED has FDR < 0.05.

We obtained the intersection between DEGs and GO terms. We subsequently obtained both significant GOs and genes belonging to the significant GO terms with the thresholds of P value < 0.01 and FDR < 0.05. The DEG-GO network was constructed using the Cytoscape software (Cytoscape version 3.4.0, USA).

3.3. Reconstruction of Protein-Protein Interaction

The protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were constructed using BisoGenet plugin of Cytoscape software via retrieving the interactions between DEGs. BisoGenet is a popular plugin for biological network construction, visualization, and analysis (20). This plugin permits searching on well-known interaction databases including database of interacting proteins (DIP), biological general repository for interaction datasets (BioGRID), Human protein reference database (HPRD), biomolecular interaction network database (BIND), molecular INTeraction database (MINT), and IntAct (21-26), which represent the major repositories of PPIs from multiple organisms.

3.4. Network Topological Analysis

To predict the key regulators in the different phases of CHB based on hub type variations, topological analysis was performed for two resulted PPI networks (IT-IA and IA-IC) using the Network Analyzer plugin of Cytoscape. This plugin uses several topological algorithms to examine important nodes/hubs and fragile motifs in an interactome network. In the present study, three centrality measures including, Degree, Closeness, and Betweenness were used to select hub genes (27). Degree is defined as the number of nodes that a focal node is connected to, and measures the involvement of the node in the network. Generally, nodes with higher degree of centrality within biological networks tend to have biologically important roles in the regulation of cellular processes. Closeness centrality was defined as the inverse sum of the shortest distances to all other nodes from a focal node.

4. Results

4.1. Distinct Gene Expression Profiles Characterize Different CHB Phases

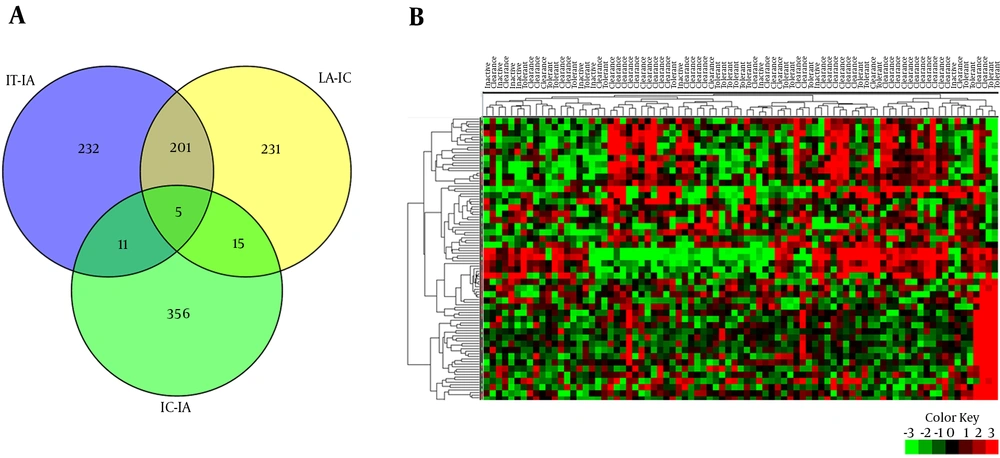

22 patients with IT, 50 with IA, and 11 with IC were enrolled in this study. Demographic characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. Comparative analysis was performed between IT-IA and IA-IC tissue samples to identify genes with significant differential expression levels. 449 DEGs were obtained in the IT-IA patients, including 398 upregulated and 51 downregulated genes at an FC cutoff of ≥ 1 and FDR-adjusted P value < 0.01. Furthermore, 452 genes were differentially expressed between IA and IC phases of CHB infection, from which, 17 genes were upregulated and 435 downregulated. The CCL20 (chemokine [C-C motif] ligand 20), KRT23 (keratin 23 [histone deacetylase inducible]), and HKDC1 (hexokinase domain containing 1) were the three most upregulated genes in the IA patients compared to IT patients. Similarly, the three most downregulated genes were CCL20, CCL19, and IGLV3-19 (immunoglobulin lambda variable 3 - 19) in the IC patients compared to IA patients. In addition, hepatic transcriptomes of the IT and IC patients were mainly similar, and 387 DEGs were obtained in these groups, including 297 upregulated and 90 downregulated genes. To identify the differences in gene expression, a supervised hierarchical clustering was performed on the set of DEGs (n = 109), at an FC cutoff of ≥ 3 and P value < 0.01. Based on the expression profiles of these selected genes, we were able to differentiate the different clinical phases of CHB (Figure 2).

A PPI was created for each DEG list resulted from the analysis of IT-IA and IA-IC gene expression profiles. The number of nodes-edges in the PPIs of IT-IA and IA-IC were 397 - 222 and 435 - 291, respectively. More details on each PPI structure are shown in Table 2.

| Parameter | Immune Tolerant (n = 22) | Immune Clearance (n = 50) | Inactive Carrier (n = 11) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | < 0.54 | |||

| Male | 14 (63.6) | 36 (72) | 9 (81.8) | |

| Female | 8 (36.4) | 14 (28) | 2 (9.1) | |

| Age | 37.22 ± 10.23 | 41.98 ± 12.33 | 44.27 ± 12.35 | 0.187 |

Demographic Characteristics of Patients in Different HBV Chronic Phasesa

| Parameter | Definition | IT-IA | IA-IC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of nodes | Component of a network (e.g. a gene or a protein) | 397 | 435 |

| Number of edges | Number of interactions between two nodes | 222 | 291 |

| Network diameter | The highest distance between two nodes | 13 | 12 |

| Network radius | The smallest distance between two nodes | 1 | 1 |

| Network centralization | How does the network topology resemble a star structure? (A value between 0 and 1) | 0.29 | 0.047 |

| Shortest paths | Minimum numbers of edges form a path. Shortest paths defined as distance | 7350 (4%) | 12058 (6%) |

| Characteristics path length | Distance between two connected nodes | 5.069 | 4.483 |

| Network density | How densely is the network populated with edges? (A value between 0 and 1) | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Clustering coefficient | A measure of the degree to which nodes in a graph tend to cluster together | 0.016 | 0.029 |

| Network heterogeneity | Tendency of a network to contain hub nodes | 2.264 | 2.334 |

| Number of connected components | Number of subnetworks that constitute a network | 297 | 307 |

| Average number of neighbors | The average connectivity of a node | 0.599 | 0.832 |

The Architecture and General Properties of PPI Between Different Phases of Chronic HBV Infection

PPIs were reconstructed for DEGs with significant expression change (FC ≥ 1 and FDR < 0.01). All sub-networks of the PPIs were reconstructed using BisoGenet plugin of Cytoscape software and the main sub-networks were extracted subsequently from each PPI (Figure 3). Number of sub-networks (number of connected components) that constitute IT-IA and IA-IC networks were calculated as 297 and 307, respectively. It should be noted that pairwise connected nodes falsely increased the number of connected components.

Furthermore, topological analysis of the PPIs indicated that both networks illustrated the small-word property and scale-free pattern, two well-known characteristics of most biological networks (data not shown). In addition, neighborhood connectivity distribution followed an assortative architecture indicating that nodes had tendency to connect with nodes of similar connectivity.

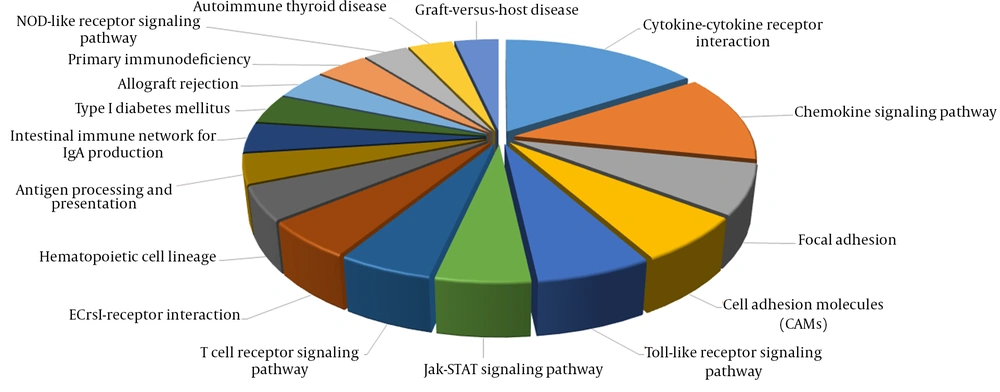

4.2. Gene Ontology and KEGG Pathway Analyses of DEGs

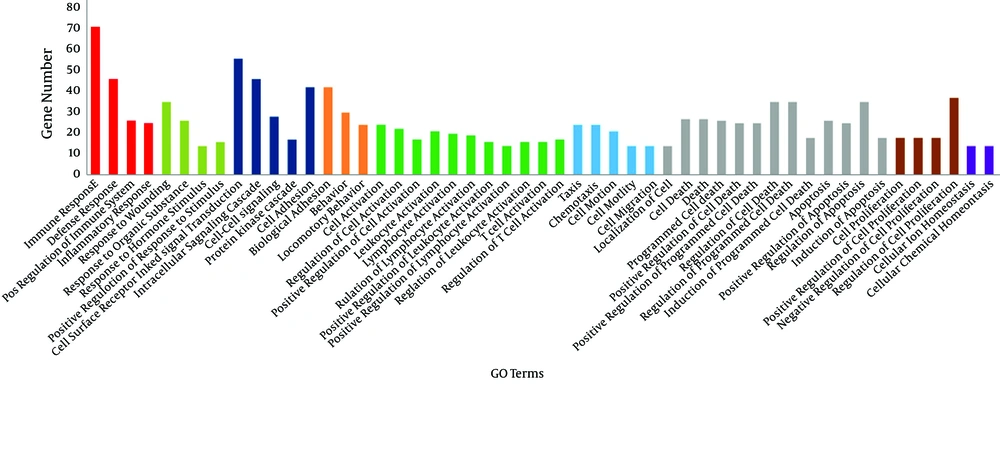

To examine the roles and functions of genes, the biological processes involved by IT-IA and IA-IC DEGs were identified by GO enrichment analysis using DAVID. In total, 237 GO terms were obtained in the IT-IA samples, as shown in Figure 4. The network of genes affected by immune clearance phase augmented with immune responses, and most of them were being upregulated. Gene ontology analysis showed that the other significantly enriched GO terms of upregulated DEGs included defense response, inflammatory response, T-cell activation, and chemotaxis. In addition, 295 GO terms were identified in the IA-IC patients. GO enrichment analysis using DAVID revealed that the majority of them were downregulated which included immune response, cell surface receptor linked signal transduction, defense response, cell adhesion, intracellular signaling cascade, T-cell activation, and regulation of programmed cell death.

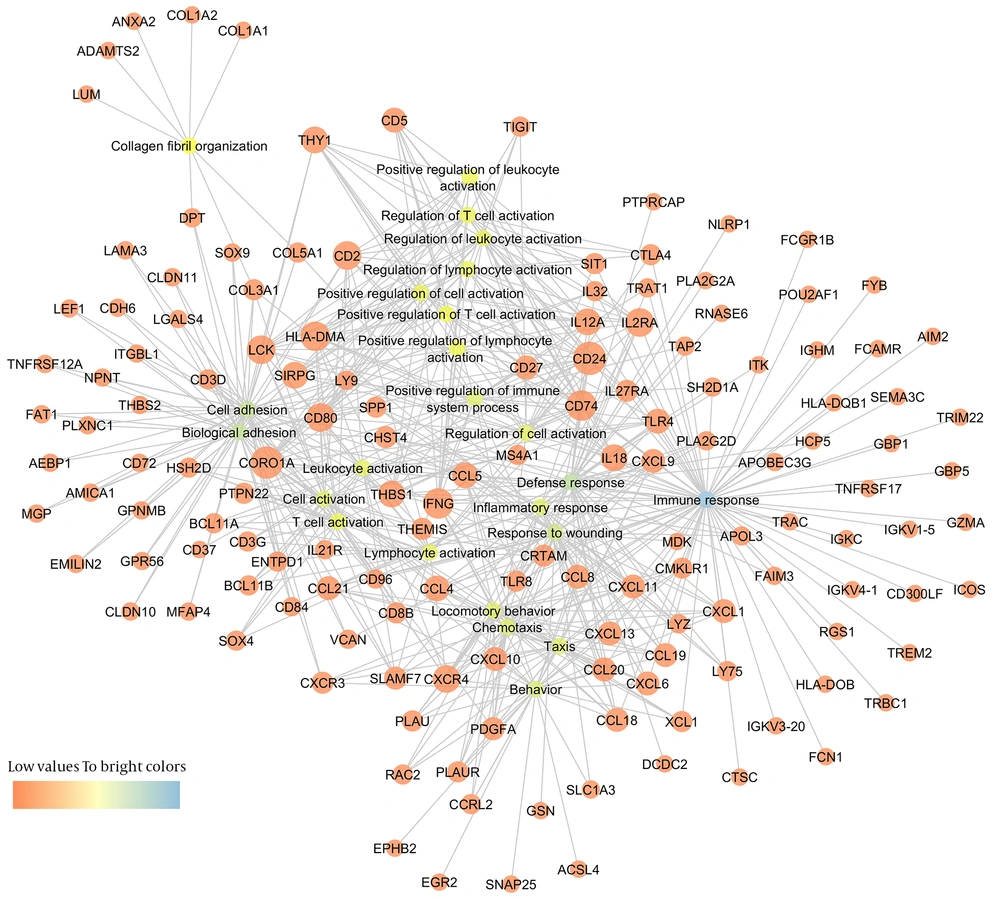

To better understand the connections between differentially expressed genes and GO terms, a DEG-GO network was constructed with the GO terms and DEGs using the Cytoscape Software (Figure 5). The degree of any particular gene was determined by the number of GO terms regulated by the gene in the network. The CD24 (18 degrees), CORO1A (coronin, actin binding protein, 1A: 17 degrees), INFG (interferon-γ: 15 degrees), CD74 (15 degrees), HLA-DMA (14 degrees), LCK (13 degrees), CD80 (13 degrees), CD2 (13 degrees), IL2RA (13 degrees), and CXCR4 (12 degrees) were significantly regulated differentially in immune tolerant samples compared to the immune clearance samples. The important GO terms, defined as the most highly regulated by the altered DEG, were involved in immune response (71 degrees), defense response (46 degrees), cell adhesion (42 degrees), biological adhesion (42 degrees), and response to wounding (35 degrees).

In addition, several significantly altered KEGG pathways were identified. The KEGG pathway analysis demonstrated that immune response genes were upregulated in the immune clearance phase (Figure 6). By contrast, immune response genes were downregulated in the IC phase of CHB infection.

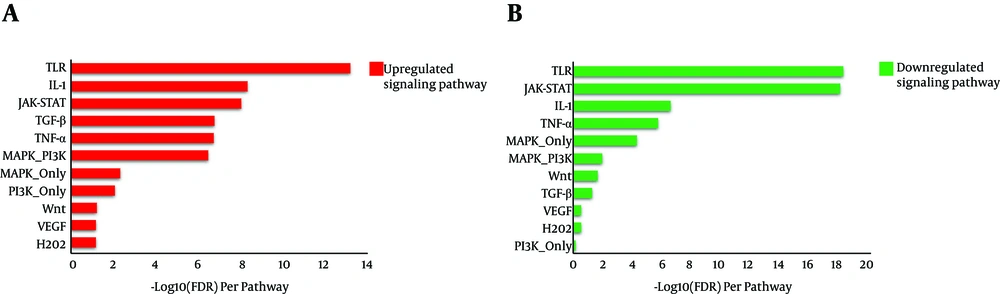

Gene enrichment was performed for both IT-IA and IA-IT networks using the SPEED web server (http://speed.sys-bio.net/). The aim of the SPEED web server is to identify the causal signaling pathways in a given list of input human genes. Therefore, genes are annotated based on causal influences of pathway perturbations as opposed to pathway memberships alone (Figure 7). Thus, we entered the input DEG lists of IT-IA and IA-IC, which adopted from liver biopsy samples into the web server. The SPEED analysis of DEGs from both IT-IA and IA-IC samples indicated that the majority of these genes mainly involved in immune response signaling pathways (Table 3). However, the immune response was strongly upregulated in IT-IA state. Investigating for lists of deregulated genes using the SPEED indicated TLR, IL-1, and JAK-STAT as the top-ranking pathways. However, there was a significant negative correlation between these genes in IT-IA and IA-IC transitions (P value < 0.05).

| Pathway | IT-IA | IA-IC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes in list | P Value | FDR | Genes in list | P Value | FDR | |

| TLR | 25 | 9.77e-15 | 5.02e-14 | 30 | 1.94e-19 | 4.03e-19 |

| IL-1 | 17 | 1.67e-09 | 4.03e-09 | 15 | 1.14e-07 | 2.12e-07 |

| JAK-STAT | 15 | 4.54e-09 | 7.22e-09 | 25 | 1.77e-19 | 6.3e-19 |

| TGF-β | 15 | 9.18e-08 | 1.55e-07 | 6 | 0.06 | 0.0493 |

| TNF-α | 20 | 1.37e-07 | 1.63e-07 | 19 | 8.89e-07 | 1.52e-06 |

| MAPK-PI3K | 13 | 4.07e-07 | 3.06e-07 | 7 | 0.00845 | 0.0104 |

| MAPK-only | 20 | 0.0055 | 0.0044 | 26 | 4.39e-05 | 4.48e-05 |

| PI3K-only | 5 | 0.00897 | 0.00836 | 1 | 0.733 | 0.624 |

| Wnt | 4 | 0.0739 | 0.0613 | 5 | 0.0232 | 0.0198 |

| VEGF | 3 | 0.0908 | 0.067 | 2 | 0.298 | 0.269 |

| H2O2 | 3 | 0.106 | 0.0681 | 1 | 0.327 | 0.279 |

SPEED Analysis of Deregulated Genes and Pathways Enriched by DEGs

4.3. Detection of Hub Genes

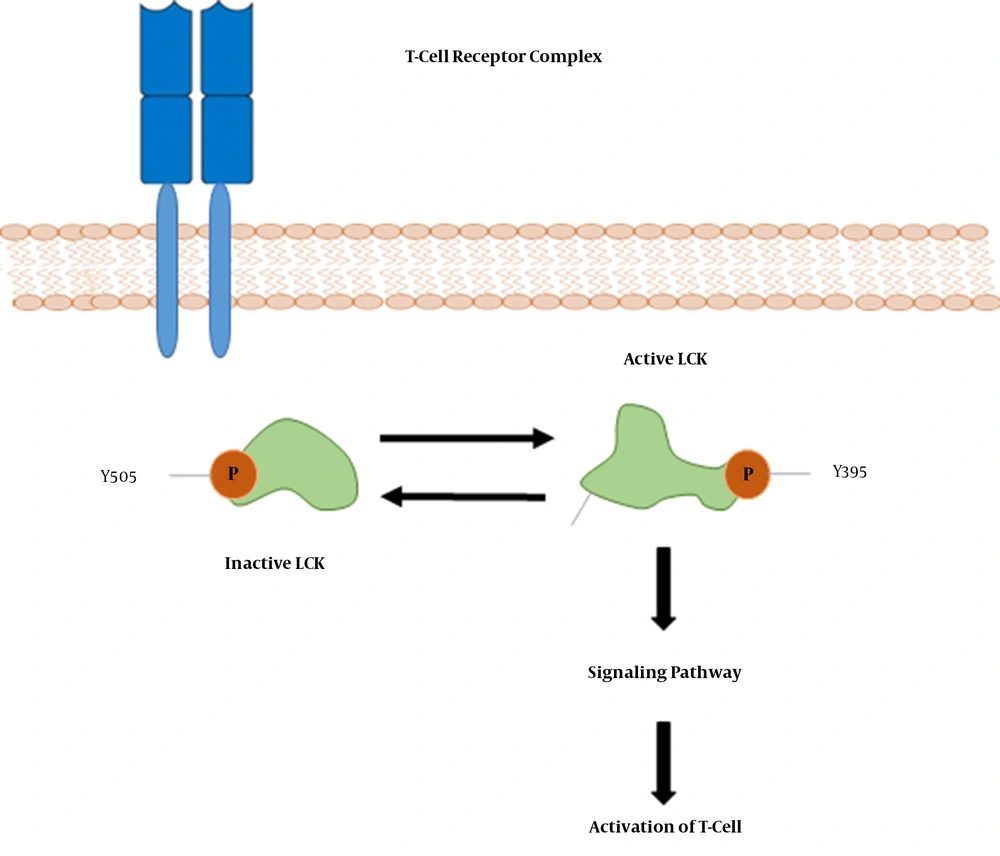

All constructed PPIs were topologically analyzed using the NetworkAnalyzer plugin of the Cytoscape. As mentioned before, both networks (IT-IA and IA-IC) had a scale-free pattern, assortative architecture, and small-word property. In each PPI, some genes were categorized based on their degree, Betweenness Centrality, and Closeness Centrality scores (Table 4). Some of the important hub genes in the BisoGenet-derived PPI were LCK, CXCR3, VCAN, MYC, STAT1, IKZF3, CFTR, BTK, and SH2D1A in IT-IA patients. Functional analysis of the hub genes indicated that these genes were mainly involved in immune related response. Several genes including LCK, SYK, VCAN, PTPRC, ZAP70, ITGA4, HLA-B, and STAT1 were among the hub genes in the IA-IC network. LCK (encoding a tyrosine kinase) was determined as the most important gene of both sub-networks. However, LCK gene expression was significantly downregulated in the IC phase. Furthermore, in both networks, it was interesting to notice that most of the genes connected with LCK were mainly involved in immune response.

| Gene Name | Degree | Betweenness Centrality | Closeness Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|

| IT-IA | |||

| LCK | 14 | 0.353735 | 0.268987 |

| CXCR3 | 10 | 0.228259 | 0.276873 |

| VCAN | 10 | 0.110224 | 0.238764 |

| MYC | 10 | 0.232404 | 0.258359 |

| STAT1 | 8 | 0.128697 | 0.245665 |

| IKZF3 | 8 | 0.340868 | 0.288136 |

| CFTR | 7 | 0.100047 | 0.202381 |

| BTK | 7 | 0.089528 | 0.273312 |

| SH2D1A | 7 | 0.092437 | 0.216837 |

| BARD1 | 6 | 0.274622 | 0.227273 |

| JAK3 | 6 | 0.381069 | 0.300353 |

| CCL5 | 6 | 0.130373 | 0.256024 |

| PDGFA | 6 | 0.022549 | 0.164729 |

| COL1A1 | 6 | 0.213352 | 0.194064 |

| CXCR4 | 6 | 0.102558 | 0.252226 |

| IA-IC | |||

| LCK | 23 | 0.325983 | 0.356209 |

| SYK | 16 | 0.329859 | 0.357377 |

| VCAN | 11 | 0.118146 | 0.267813 |

| PTPRC | 11 | 0.056812 | 0.286842 |

| ZAP70 | 11 | 0.042304 | 0.292225 |

| ITGA4 | 11 | 0.212197 | 0.318713 |

| HLA-B | 10 | 0.211426 | 0.29863 |

| STAT1 | 10 | 0.216517 | 0.344937 |

| CCR5 | 9 | 0.091204 | 0.301105 |

| PRKCQ | 8 | 0.063473 | 0.280928 |

| CD74 | 8 | 0.098669 | 0.235421 |

| LCP2 | 8 | 0.026027 | 0.309659 |

| FUS | 8 | 0.172478 | 0.30791 |

| CXCR4 | 7 | 0.120661 | 0.290667 |

| BTK | 7 | 0.033154 | 0.281654 |

The Top 15 Hub Genes Obtained from Analysis of the IT-IA and IA-IC Networks

5. Discussion

Chronic hepatitis B infection is a dynamic disease with an unpredictable history. In patients with CHB, the presence of positive HBeAg usually indicates a high level of viral replication and thus infectivity. The immune tolerant and early immune clearance phases are characterized by positive HBeAg. HBeAg seroconversion hallmarks the disappearance of HBeAg and appearance of anti-HBe. The progression of CHB is divided into a number of clinical phases with different patterns of HBV viral load, HBeAg/anti-HBe status, and serum ALT levels, indicating different interactions in the host-virus immune relationship (4).

In the present study, we applied an advanced system biology approach to find out host factors in the liver transcriptome of each clinical phase of chronic HBV infection. Our results showed that in liver, immune response-related genes are transcriptionally most upregulated in IA phase, compared to the IT patients. Some GO biological processes and KEGG pathways were overrepresented by DEGs. While immune response was revealed as the most significantly deregulated biological processes, the top KEGG pathways were the major paths in immune response. Consistent with our study, a previous liver transcriptome study in IA patients, compared to IT patients, indicated higher activities of all identified immune-related modules (plasma cells, B cells, natural killer cells, T-cells, and interferon-stimulated genes) (28). However, in addition to the pathways obtained from KEGG molecular pathways or gene ontology (18, 29), we integrated microarray data with high throughput PPI data and searched for deregulated networks in IT-IA and IA-IC patients. One of the largest constituent functional groups was found to be immune response by ingenuity pathway analysis. In addition, SPEED analysis of DEGs revealed that most of these genes were involved in immune response signaling pathways from which, TLR, IL-1, and JAK-STAT pathways were among the top-ranking pathways. However, the immune response was strongly upregulated in IA patients and downregulated in IC patients. Previously, microarray gene expression analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of different clinical phases of CHB patients demonstrated that immune related genes significantly upregulated in immune clearance compared to other CHB phases (28). This suggests that their intrahepatic counterparts reflect PBMC transcriptional activities.

Our network-based study renders a model to extract information from high suitable genomic microarray in human samples. We demonstrated that patients in immune clearance phase could be discriminated from immune tolerant patients based on their high T-cell activation. In addition, DEG-GO network obtained from IT-IA patients revealed that most important GO terms were involved in immune response (Figure 5). Spontaneous hepatitis flare (acute exacerbations) with sudden elevation of serum ALT over five times the upper limit of normal or a greater than 3-fold increase in ALT are often hallmarks of the immune clearance phase (30, 31). Previous studies have revealed that immune response against HBV antigens mediated by HLA-class I antigen-restricted, cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) and its downstream mechanisms can cause the hepatitis flares. Higher ALT levels reflect a stronger immune response and a broader hepatolysis that, in severe cases, may cause decompensation and failure. In contrast, higher ALT also reflects a more robust immune clearance of HBV and, therefore, a higher chance of HBV-DNA clearance and HBeAg seroconversion, as outcomes of natural course and drug therapy setting (32). The reasons for spontaneous acute hepatitis flares are yet to be uncovered; however, subtle changes in immunological controls of viral replication could provide an explanation for these flares. Several studies have shown that acute hepatitis flares are often preceded by an increase in the serum levels of HBV DNA (33-35) and enhanced T-cell response to hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) and HBeAg (36).

We speculate that immune tolerant phase is due to the induction of the inhibition of inflammatory and immune response. We are in much doubt that tolerance is conducted strictly against the virus. Previous studies have shown that innate immune response is inhibited in the first 24 hours of hepatocyte infections and it lasts for 12 days after infection, which is considered persistent infection in cell culture (37). In addition, in early stages of the infection, HBV components and/or host factors associated with HBV presence in the viral inoculum (but in the absence of HBsAg or HBeAg) were necessary and sufficient to suppress the innate immune response driven by the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) sensors and may be responsible for the inhibitory phenotype and its maintenance in the long-term (38). These studies highlighted that HBV serves as a “stealth” virus and leads to a decreased expression of several pro-inflammatory/antiviral cytokine gene expressions (12, 38).

The immune tolerant phase is defined as positive HBeAg, high levels of HBV DNA and serum aminotransferases. This phase is usually asymptomatic and in liver biopsy is at least related to the fibrosis. Immunological characteristics of immune tolerant patients suggested that there is no pattern of tolerogenic T-cell (39). The present study showed that T-cell activation- related genes were upregulated in the immune clearance phase, compared to the other clinical phases (Figure 4). HBV is a noncytopathic virus; therefore, it does not directly cause the liver damage. In fact, the infiltration of immune cells leads to the liver damage. HBV-specific T-cells play an important role in eliminating HBV-infected hepatocytes (40). They are also involved in the liver damage during ALT flares (36). When the initial immune response is not able to eliminate the virus, the accumulation of viral antigen load in the liver and blood will cause the elimination and dysfunction of HBV-specific T-cell that eventually leads to the chronicity (6, 41). According to previous studies, the severe events of inflammation in the liver that are associated with a significant increase in ALT are linked to the intrahepatic recruitment of the granulocytes, monocytes, and non-antigen-specific T-cells (42-45). We hypothesize that the lack of upregulation of T-cell activation genes and other immune response genes may allow HBV to avoid elicitation of immunity for a long period of time, which may aid in establishing persistent infection.

Moreover, topological analysis indicated that LCK was the most important “hub” genes involved in the IA and IC phases. In addition, other immune response-associated genes were found as important hub genes in the IA and IC phases. LCK (lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase) is a 56-kDa protein, and phosphorylates tyrosine residues of certain proteins involved in the intracellular signaling pathways of lymphocyte (Figure 8). LCK is most commonly found in T-cells, which is loosely associated with the tail of CD4 and CD8 co-receptor proteins. LCK plays a critical role in T-cell receptor associated signal transduction pathways (46-48). To the best of our knowledge, increased expression of the LCK gene in immune clearance patients has not been reported. However, further comparison and experimental validation of this gene is required to verify our results.

In conclusion, based on the bioinformatics methods used in the current study, CHB clinical phases are characterized by differentially expressed genes associated with the immune response. LCK hub gene might help improve the pathogenesis of different phases of CHB and may serve as a potential therapeutic target and molecular marker contributing to the prevention and treatment of HBV.