1. Context

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection is the most common type of acute viral hepatitis and proposed as an important public health issue (1). HAV is a non-enveloped single-stranded RNA virus which is categorized as a member of the Heparnavirus genus in the family of Picornaviridae (2). Annually, about 1.5 million cases of HAV infection occur worldwide and most of them are in less developed countries (1). Clinical manifestations of HAV infection depend on the age of infected persons. Most of the HAV-infected patients aged below 6 years are asymptomatic (3, 4). But as their age increases, the situation can be more dangerous. The HAV infection can lead to liver failure and even death in approximately 0.2 % of symptomatic cases (5). It is well known that the incidence of HAV infection is strongly associated with the socioeconomic status of a country. As socioeconomic indicators improve, having access to the safe and clean water, hygiene, and sanitation increases (6). Over the time, it can clearly cause a decrease in the rate of infection and consequently may lead to a shift in the epidemiological pattern as well as a change in the age of HAV-infected persons from childhood to adulthood (7, 8). Most of the people in Eastern Mediterranean region (EMR) of WHO and Middle East are living in middle -income countries and are involved in viral hepatitis as a major health issue (9, 10). Also, it is said that most of the countries in this region have a high endemicity of HAV infection (7, 11). Considering the changes in socioeconomic status of these countries, determining the epidemiological pattern of HAV infection can be helpful for healthcare policy makers to make better decisions about future plans of controlling this infection and selecting and running the cost-effective preventive methods (2, 11). Therefore, to provide a more exact and up-to-date estimation on the epidemiology of this infection, we conducted a systematic review on the literature reporting the prevalence of HAV infection in the EMR and ME.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Data Resources and Search Strategies

We conducted a comprehensive systematic search in the electronic databases including PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct, and Web of science. For this purpose, first, we developed an exact and sensitive search formula for PubMed with appropriate combination of keywords both in medical subject headings (MeSH) and in free texts. The keywords were “hepatitis A”, “HAV” and name of middle eastern and WHO EMR countries such as Afghanistan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Occupied Palestinian Territory (Israel), Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Yemen. After establishing this search strategy, we modified it for using in other databases according to their search rules. We applied no language limitation and considered a time period between January 1990 and July 2016 in our search formula. Furthermore, we used Google scholar to find grey literature and also check the sensitivity of our search strategy. We continued our search in Google scholar until finding 50 unrelated serial titles. In addition to aforementioned databases, we searched national and regional databases including scientific information database, PakMedinet, and Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region of WHO. After all, we checked references of included papers to retrieve any related missing document.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Observational studies published between January 1990 and July 2016 that clearly stated data regarding HAV Ab (IgG), performed in the general population, among blood donors, health-care workers, soldiers, and in different age categories including children, adolescents, and adults were considered for inclusion in this systematic review. We excluded studies if they were letters or correspondence, case report, systematic review, or meta-analysis. We also excluded studies carried out in high risk populations (e.g. suspected to viral hepatitis) and in age groups of less than six months due to confounding with maternal antibodies.

2.3. Quality Assessment

We assessed the quality of included papers with regard to the following three factors: 1) sampling method (cluster sampling proportional to size, simple random cluster sampling, simple random sampling without clustering, non-random sampling and not reported sampling method), 2) age coverage and similarity to general population, and 3) study level (national, provincial, regional, and sub- regional). We considered a scoring system adopted from a previously used critical appraisal form (12). Based on this system and considering the mentioned factors, the included papers were categorized as low, moderate, and high quality ones. We applied the results of this assessment in our sensitivity analysis.

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

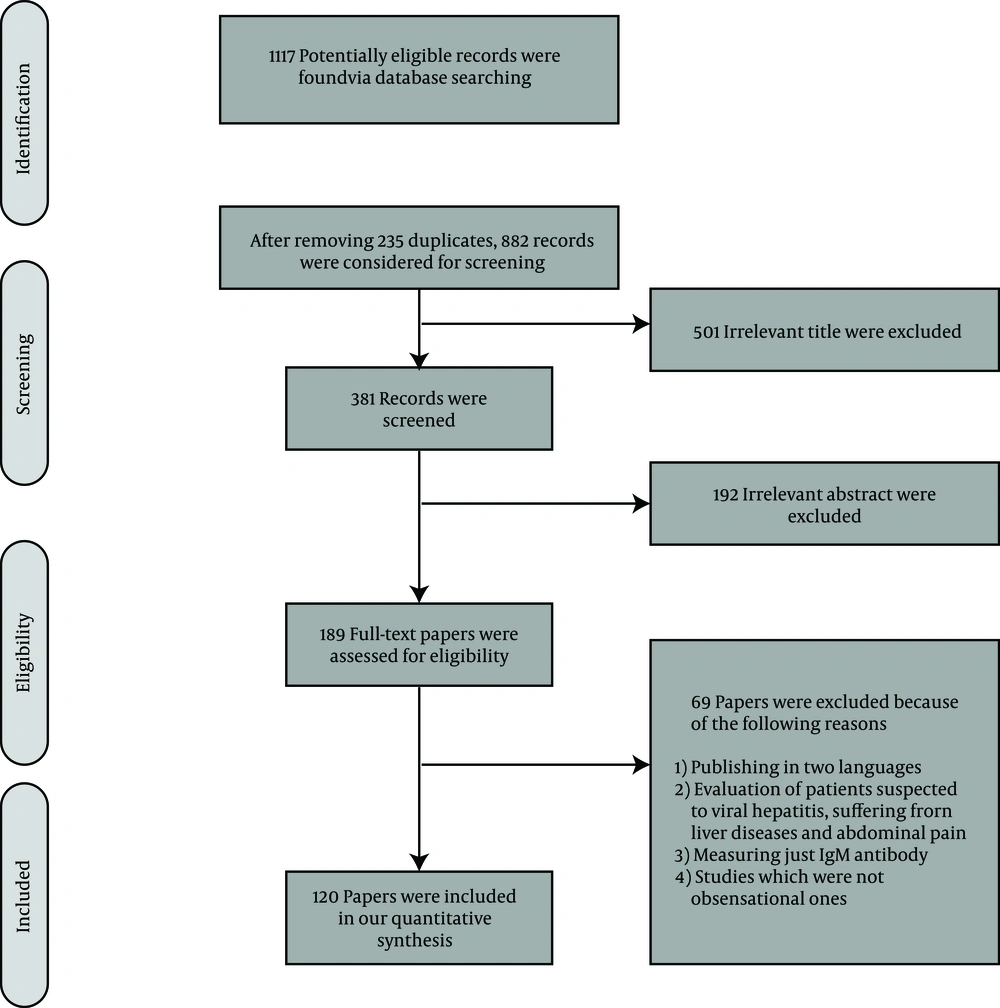

All steps in this systematic review were in line with criteria proposed in PRISMA guideline (13). Two authors (MS and MSR-Z) independently reviewed all the records identified through databases searching in different levels such as title, abstract, and full-text. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved through mutual discussion or based on the opinion of the third author (SMA). The appropriate studies were selected according to the eligibility criteria. For papers in Turkish, Arabic, or French, we used Google translator. Data presented in the papers including first author, publication year, study origin, target population, sample size, and number of positive cases for HAV Ab were extracted.

2.5. Data Analysis

We estimated the prevalence of HAV infection based on the pooled data from all the included studies for each country. Pooled analysis has been used in previous epidemiological studies (14). To obtain the number of people with positive results for HAV Ab living in the evaluated countries, we extrapolated the estimated prevalence rate to the population of each country. The prevalence rate in ME and WHO EMR as well as in total was calculated based on the calculated prevalence rates in all the countries, and weighted according to the population size of each country (from the last census in 2015, based on UN reports). In all steps, 95% confidence interval (CI) was obtained from Jeffreys method in STATA software (version 11.0). For sensitivity analysis, we used the results of quality assessment and excluded data of low quality studies in the final pooled analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Study Screening and Characteristics of Included Studies

After removing duplicate records, 882 papers were considered for screening. In the steps of title and abstract screening, we found 693 irrelevant records and therefore assessed 189 full-text papers for inclusion in our systematic review according to our eligibility criteria. Finally, we included 120 papers with total sample size of 111326 participants (Figure 1).

We found no eligible study for Bahrain, Djibouti, Libya, Oman, Qatar, and Sudan. Also, Afghanistan, Jordan, Kuwait, Palestine, Morocco, Somalia, Syria and Yemen each one only had one appropriate study for inclusion in our systematic review. Turkey (39) and Iran (32) had the most related studies. Among all the included studies and based on our quality assessment, we found 51 studies with low quality. No study was excluded based on the results of quality assessment but the remained 51 studies were not used in our sensitivity analysis. The characteristics of the included studies and results of quality assessment have been shown in Supplementary File.

3.2. Estimating HAV Prevalence Rate

According to Table 1, HAV prevalence in Middle East and WHO MER as well as in total was 61.60 (61.31 - 61.89), 65.74 (65.39 - 66.09), and 62.60 (62.32 - 62.89), respectively. The most HAV prevalence rates were related to Afghanistan (99.01 (95.51 - 99.89)), Iraq (96.35 (95.97 - 96.70)), Somalia (96.00 (94.16 - 97.33)), and Palestine (93.70 (90.96 - 95.77)). The results for these prevalence rates were not changed after removing low quality studies except for Somalia which had one low quality study (Table 2). Cyprus had the lowest prevalence rate of HAV (2.61 (1.53 - 4.17)). Cyprus, UAE, and Kuwait had a prevalence rate of below 50%, while the rates of other countries were above the mentioned value.

| Country Name | Number of Studis | Number of Participants | Prevalence Estimates (95% CI) | Country Population | Estimated HAV Ab Positive Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 1 | 102 | 99.01 (95.51 - 99.89) | 32530000 | 32207953 |

| Cyprus | 2 | 573 | 2.61 (1.53 - 4.17) | 1165000 | 30406 |

| Egypt | 5 | 1345 | 71.52 (69.06 - 73.88) | 91510000 | 65447952 |

| Iran | 32 | 23963 | 62.24 (61.62 - 62.85) | 79110000 | 49238064 |

| Iraq | 2 | 10247 | 96.35 (95.97 - 96.70) | 36420000 | 35090670 |

| Israel | 12 | 5707 | 60.60 (59.33 - 61.87) | 8463000 | 2679732 |

| Jordan | 1 | 3066 | 51.01 (49.24 - 52.77) | 7593000 | 3873189 |

| Kuwait | 1 | 2851 | 28.62 (26.98 - 30.30) | 3890000 | 1113318 |

| Lebanon | 3 | 1346 | 77.71 (75.43 - 79.87) | 5851000 | 4546812 |

| Morocco | 1 | 150 | 51.00 (42.71 - 23.86) | 34380000 | 17533800 |

| Pakistan | 4 | 902 | 83.92 (81.42 - 86.21) | 188900000 | 158524880 |

| Palestine | 1 | 396 | 93.70 (90.96 - 95.77) | 1715000 | 1606955 |

| Saudi Arabia | 6 | 20671 | 56.31 (55.63 - 56.98) | 31500000 | 17737650 |

| Somalia | 1 | 596 | 96.00 (94.16 - 97.33) | 10790000 | 10358400 |

| Syria | 1 | 849 | 88.81 (86.55- 90.79) | 18500000 | 16429850 |

| Tunisia | 5 | 3739 | 80.04 (78.74 - 81.30) | 11110000 | 8892444 |

| Turkey | 39 | 33657 | 57.01 (56.48 - 57.54) | 78670000 | 44849767 |

| United Arab Emirates | 2 | 628 | 20.54 (17.52 - 23.83) | 9160000 | 1881464 |

| Yemen | 1 | 538 | 86.61 (83.54 - 89.29) | 26830000 | 23237463 |

| Total | 120 | 111326 | 62.60 (62.32 - 62.89) | 678087000 | 424482462 |

| Total for Middle East | 108 | 105837 | 61.60 (61.31- - 61.89) | 432907000 | 266670712 |

| Total for WHO EMR | 67 | 71389 | 65.74 (65.39 - 66.09) | 587767000 | 386398025 |

Hepatitis A Virus Antibody (IgG) Seroprevalence and Number of People Living with Positive Result Test for This Antibody in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region and Middle East

| Country Name | Number of Studies | Number of Participants | Prevalence (95% CI) | Country Population | Estimated HAV Ab Positive Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 1 | 102 | 99.01 (95.51 - 99.89) | 32530000 | 32207953 |

| Cyprus | 1 | 385 | 0.77 (0.21 - 2.06) | 1165000 | 8971 |

| Egypt | 2 | 524 | 45.99 (41.75 - 50.27) | 91510000 | 42085449 |

| Iran | 20 | 16374 | 64.42 (63.68 - 65.15) | 79110000 | 50962662 |

| Iraq | 2 | 10247 | 96.35 (95.97 - 96.70) | 36420000 | 35090670 |

| Israel | 6 | 2460 | 83.98 (82.49 - 85.39) | 8463000 | 7107227 |

| Jordan | 1 | 3066 | 51.01 (49.24 - 52.77) | 7593000 | 3873189 |

| Kuwait | 1 | 2851 | 28.62 (26.98 - 30.30) | 3890000 | 1113318 |

| Lebanon | 2 | 1508 | 54.97 (52.45 - 57.47) | 5851000 | 3216294 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 258 | 55.81 (49.71 - 61.78) | 188900000 | 125425090 |

| Palestine | 1 | 538 | 86.61 (83.54 - 89.29) | 1715000 | 23237463 |

| Saudi Arabia | 6 | 20671 | 56.31 (55.63-56.98) | 31500000 | 17737650 |

| Syria | 1 | 849 | 88.81 (86.55 - 90.79) | 18500000 | 16429850 |

| Tunisia | 3 | 3234 | 88.43 (87.29 - 89.50) | 11110000 | 9824573 |

| Turkey | 20 | 26494 | 62.88 (62.30-63.46) | 78670000 | 49467696 |

| Yemen | 1 | 538 | 86.61 (83.54 - 89.29) | 26830000 | 23237463 |

| Total | 69 | 90099 | 65.20 (64.89 - 65.51) | 678087000 | 442112724 |

| Total for Middle East | 62 | 86505 | 64.18 (64.05 - 64.32) | 478077000 | 306863061 |

| Total for WHO EMR | 42 | 60760 | 65.63 (65.51 - 65.75) | 598252000 | 392636057 |

Hepatitis a Virus Antibody (IgG) Seroprevalence and Number of People Living with Positive Result Test for This Antibody in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region and Middle East After Removing Low Quality Studies

We tried to select a sample to be more representative of general population and therefore decided to include only studies which cover all age groups because some studies had evaluated a specific age group such as children, adolescents, and adults. After removing these studies, we pooled the results of remaining studies and calculated HAV prevalence which can be found in Table 3. Based on the Table 3, the HAV prevalence in ME, WHO EMR, and in total is 67.06 (67.05 - 67.06), 69.48 (69.47 - 69.48), and 67.51 (69.47 - 69.48), respectively. Based on this analysis, Lebanon is the only country with prevalence rate of below 50%.

| Country Name | Number of Studies | Number of Participants | Prevalence (95% CI) | Country Population | Estimated HAV Ab Positive Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 1 | 102 | 99.01 (95.51 - 99.89) | 32530000 | 32207953 |

| Iran | 22 | 14464 | 65.68 (64.90 - 66.45) | 79110000 | 51959448 |

| Iraq | 2 | 10247 | 96.35 (95.97 - 96.70) | 36420000 | 35090670 |

| Israel | 5 | 3042 | 57.75 (55.97 - 59.52) | 8463000 | 4886805 |

| Jordan | 1 | 3066 | 51.01 (49.24 - 52.77) | 7593000 | 3873189 |

| Lebanon | 1 | 606 | 43.23 (39.33 - 47.20) | 5851000 | 2529387 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 11674 | 86.90 (85.26 - 86.53) | 31500000 | 27373500 |

| Syria | 1 | 849 | 88.81 (86.55 - 90.79) | 18500000 | 16429850 |

| Tunisia | 4 | 3634 | 80.87 (79.57 - 82.12) | 11110000 | 8984657 |

| Turkey | 15 | 21530 | 61.07 (60.41 - 61.72) | 78670000 | 48043769 |

| Yemen | 1 | 538 | 86.61 (83.54 - 89.29) | 26830000 | 23237463 |

| Total | 54 | 69752 | 67.51 (69.47 - 69.48) | 336577000 | 227243191 |

| Total for Middle East | 49 | 66016 | 67.06 (67.05 - 67.06) | 325467000 | 218258534 |

| Total for WHO EMR | 32 | 45180 | 69.48 (69.47 - 69.48) | 257907000 | 179199422 |

Hepatitis a Virus Antibody (IgG) Seroprevalence and Number of People Living with Positive Result test for This Antibody in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region and Middle East After Removing Papers Related to Specific Age Groups

4. Discussion

According to our systematic review, about 425 million people infected with HAV are in the countries of ME and EMR region. Data regarding HAV seroprevalence are very limited in many countries of the region. As we pointed it out before, six countries had not even one eligible study for inclusion into this project. Furthermore, there were eight other countries which had only one suitable study for inclusion. The level of endemicity for HAV infection is determined by age-specific seroprevalence of this infection (15). The low number of available studies in the region for this categorization prevented us to have that approach for analysis. However, about 63% estimated HAV seroprevalence for the whole region can be a point toward an overall intermediate-endemicity for HAV infection. This finding is similar to the result of another study which covered the time period of 1995 - 2005 and published in 2010 (16). According to this study, North Africa and ME were categorized as intermediate-endemicity for HAV. We think that these similar results in different time periods emphasize the point that countries of this region should reconsider their preventive approaches for HAV infection. It should be noted that some countries of the region such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine, and Somalia have a prevalence rate above 90% for HAV and they must be considered as hot zone for HAV infection.

We also noted a wide variation in the estimated rate of hepatitis A seroprevalence from 2.61 (1.53 - 4.17) in Cyprus to 99.01 (95.51 - 99.89) in Afghanistan. The wide variation in HAV seroprevalence rate among different countries of the region can be interpreted from various aspects. As we know, fecal-oral is the main route of HAV transmission and this can be basically prevented by some approaches such as preparing access to the clean and safe water, proper disposal of sewage, and improving personal hygiene. Considering different socioeconomic status of countries, these approaches are performed of various quality and quantity leading to the different rates of HAV prevalence. For instance, the major reasons for outbreaks of HAV in Pakistan are related to the poor sanitation conditions and therefore, using tracking systems for checking water resources for HAV have been suggested for this country (17, 18). In contrast to these high reported HAV prevalence rates, Cyprus has the lowest prevalence of HAV infection in the region. According to our eligibility criteria, we found two studies for this country; One among children and adolescents aged between 6 and 18 years which reported HAV prevalence as 0.77% (19) and another study conducted among 18-year old soldiers that reported HAV prevalence of 6.4% (20). This low prevalence rate of HAV in Cyprus has been attributed to the improved socioeconomic status of the country (19). In a study conducted among Cypriot soldiers aged 23 years in 1979, the prevalence rate of 97% has been reported for HAV infection (21). We found no other study for Cyprus published after the year 2000 and believe that a new large epidemiological study for this country may help us better evaluate HAV status in this country. A meta-analysis study has investigated seroprevalence of HAV infection in Iran with inclusion of 16 studies in a time period between 2003 and 2013 (12). The prevalence rate was calculated as 66% and after removing low and moderate quality studies, the prevalence increased to 89%. In our study, we calculated this rate as 62.24% and 64.42% with and without low quality studies, respectively. Scarce data are available from some provinces of Iran and HAV seroprevalence is various among different provinces (22). It seems that some countries like Iran are passing from intermediate- to low-endemicity area for HAV infection. Therefore, the role of vaccination should be highlighted in these countries (23). It has been reported that middle-income regions in Latin America, Eastern Europe, Asia, and Middle East have been categorized as intermediate- or low-endemicity areas, and large-scale vaccination programs for these regions may be beneficial (24). Previously, usefulness of HAV vaccination for pediatrics at risk of this infection has been well proven (25-28).

Some countries in the region are involved in war for years and this can consequently have an influence on their health status and also their neighbors’ (9). Clearly, HAV is directly associated with the primary hygiene practices and therefore, its prevalence can be increased by these conflicts. One important reason for high calculated seroprevalence of HAV in countries like Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Libya, Yemen, and Palestine is the war. International organizations should help stop these conflicts and prevent more damage to these health-related issues.

Travelling to the countries with high prevalence of HAV infection suggests an important health concern. It has been estimated that HAV attack rate for European travelers to the ME is 181/1000 per journey (29). However, these data are for more than thirteen years ago, and HAV seroprevalence may has been affected due to recent developments in Middle Eastern countries. Annually, many pilgrims from countries of the region especially Iran are traveling to Iraq; a country that has HAV prevalence rate of more than 96%. Traveling from low to higher endemicity areas can certainly affect the spread of HAV infection. In a preliminary report carried out in a single province of Iran, nine new cases of HAV were determined in just a period of less than three months. Surprisingly, all of them have had a history of recent travel to holy Karbala, Iraq, or being exposed to Karbala pilgrims as the only possible risk factor for acquiring the HAV infection (30). According to our systematic review, Saudi Arabia has HAV prevalence rate of about 56% which is low compared to the corresponding rates of many other countries of the region. It has been reported that HAV infection is common during the Islamic Hajj pilgrimage in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, especially for those pilgrims who have less than 60 years old and are from low endemic areas (31). HAV is the most common vaccine-preventable illness among international travelers, and vaccination certainly plays a crucial role for pilgrims from low endemic areas (32).

As we mentioned before, because of low number of available sero-epidemiological studies in the region, we were unable to determine an age-specific and also time-trending HAV seroprevalence rate. These two points were our main limitations in this study. To prevent the effect of countries with a large number of studies on the final HAV seroprevalence rate, instead of doing a meta-analysis, we pooled data of each country and weighted them according to their population size. There is a need for further epidemiological studies regarding HAV seroprevalence in different countries of Middle East and EMR region. Improving water and sanitation systems can cause a decrease in HAV seroprevalence and protect more susceptible people from HAV infection. We know that HAV is more sever in adults. Considering this issue, future research should focus on the change in epidemiological patterns of HAV and investigate it as an emerging threat (33). According to this study, Middle East and EMR region currently might be considered as an intermediate-endemic area for HAV infection. It highlights a constant need to monitor ongoing programs for prevention of HAV transmission which can be performed through different aforementioned approaches in different countries according to their reported HAV seroprevalence.