1. Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and the associated disease is a major worldwide health problem (1, 2). More than two billion of people exhibit evidence of past or current infection with the HBV (3, 4). There are approximately 350 million carriers of the virus, and more than 780000 people die each year due to the acute or chronic consequences of hepatitis B (5, 6).

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are known to be at risk for blood born infections, such as hepatitis B, due to occupational exposure to blood and body fluids (7, 8). The world health organization (WHO) reports that out of the 35 million HCWs worldwide, two million are exposed to the hepatitis B virus each year (4, 9). The centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) estimated that nearly one in every ten HCWs has a needle stick exposure each year (10).

The hepatitis B vaccine is the mainstay of hepatitis B prevention (6, 11). The CDC recommends that all HCWs should receive a three-dose schedule of hepatitis B vaccination (12). The vaccine is safe and effective for groups of individuals who are at high risk of infection (13, 14) and provides at least 10 years of protection in HCWs (15, 16). An anti-HB antibody level of at least 10 mIU/mL at one to three months post-vaccination is internationally accepted as a guideline for long-term protection against HBV infection (17). However, the universal rate of poor immune responses to HBV immunization among healthy people is 5% – 10% (18). The immune response and seroconversion rate depend on many factors such as the type of vaccine used and the characteristics of the vaccinated participants (19, 20).

Many approaches are recommended for persons who do not respond to the primary vaccine series, but few studies have compared their relative efficacy. The recommendations varied including additional dose at varying times, repeating the standard three-dose schedule, giving a double dose, using a higher antigen content vaccine and using intradermal instead of the standard intramuscular route of administration (21). The use of antigen pulsed blood dendritic cells (22, 23), and adjuvants using granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factors (24) are also explored (25, 26). The seroconversion rates among people adhered to this recommendation varies from 50% to 90% in different studies and different revaccination regimens (27, 28). Some studies reported excellent response rates to doubling the antigen content in the vaccine dose in immunocompromised patients and healthy non-responders (27, 29). To protect individuals at a high risk of hepatitis B, such as HCWs, effective protocols that induce seroprotective levels of anti-HB antibodies are needed. To date, few studies compared the relative effectiveness of the approaches to giving additional vaccine doses, and consequently, there is a lack of evidence-based guidelines to manage individuals who do not respond to the primary vaccine series in everyday clinical practice (30).

2. Objectives

The current study aimed to evaluate whether double doses of hepatitis B antigen vaccine could better induce protective anti-HB antibody titers (> 10 mIU/mL) than single doses in HCWs who had previously exhibited no response to the primary vaccination schedule.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study was a randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate the antibody responses to single-and double-dose hepatitis B vaccines in healthcare workers who had not responded to the primary vaccine series. This trial was conducted in all of the hospitals in Rasht, Guilan province, north of Iran in 2014. The protocol for this randomized, controlled clinical trial (IRCT201405051155N18) was approved by the ethics committee of the gastrointestinal and liver diseases research center of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, and written informed consent (per the Helsinki declaration) was obtained from each participant.

3.2. Participants

The sample size of this study was calculated as 1110 HCWs with the precision of 0.01 and type one error of 0.05. This number was considered based on the prevalence of HBsAg positivity, 2.9%, in a study conducted among HCWs in Fars province, Iran (31). The study assessed the antibody responses of the above mentioned samples working in the hospitals of Rasht vaccinated, one to ten years prior to the study, with the hepatitis B vaccine, according to the routine immunization schedule(i e, three doses with intervals of one and six months). Ninety-one HCWs with anti-HBs titers ≤ 10 mIU/mL were defined as non-protected and were included in the trial.

The following general exclusion criteria were applied: a previous history of abnormal serum transaminase activities or a history of immune deficiency, treatment with immune suppressive drugs within six months prior to the study, the receipt of blood products within the past three months, a positive HBS Ag or HCV Ab test and pregnancy.

3.3. Intervention

The enrolled HCWs were randomized into two groups via a random allocation sequence (block size 25). The first group received single doses of the HB vaccine (Euvax B, hepatitis B vaccine recombinant) containing 20 µg of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) developed by Sanofi Pasteur Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand, and the second group received double doses of the HB vaccine (two doses of the HB vaccine containing 20 µg for a total of 40 µg of the HBsAg) in two forearms at the same time. All vaccines were intramuscularly administered in the deltoid region by trained nurses with 23G (25 mm) needles. One and six months after the first dose, the antibody responses to the HB vaccines were re-evaluated in the two groups, and the participants who had not responded (anti-HBs titer ≤ 10 mIU/mL) at each time point received a second and third doses of the HB vaccine that were similar to the first dose (i.e. single or double doses).

3.4. Measurement

Five-milliliter blood samples were obtained on days 0, 28, 168 and 196 from all participants for the serological tests. The blood samples were evaluated for HBsAg, anti-HBs and HB core antibodies (anti-HBc) for the seroconversion analyses. The anti-HBs antibody level was measured using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Diapro Diagnotic Bioprobes Milano, Italy). Anti-HB titers ≤ 10 mIU/mL were defined as non-protective. The study aimed to compare the percentages of participants with non-protective anti-HB levels after booster vaccinations with single and double doses of HBsAg.

Using a digital SECA scale with an accuracy of 0.5 kg and a meter tape, body mass index (BMI) was measured.

3.5. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20 (Released 2011, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The findings are shown as relative frequencies, means and standard deviations. The different rates of participants with non-protective anti-HB levels and demographic variables between the two groups (i.e. the single-dose and double-dose groups) were assessed by independent T-test for normally distributed data (diagnosed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) or Mann-Whitney U statistics (for not normally distributed data) and the chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests (for qualitative data). The total vaccine efficacy was estimated using the generalized estimating equations (GEE). All tests were two-sided, and P values < 0.05 were considered significant. The statistical approach was based on an intention to treat.

4. Results

Among the 1010 HCWs who received the hepatitis B vaccine, according to the routine immunization schedule, 91 subjects exhibited non-protective anti-HB levels (9% of all HCWs).

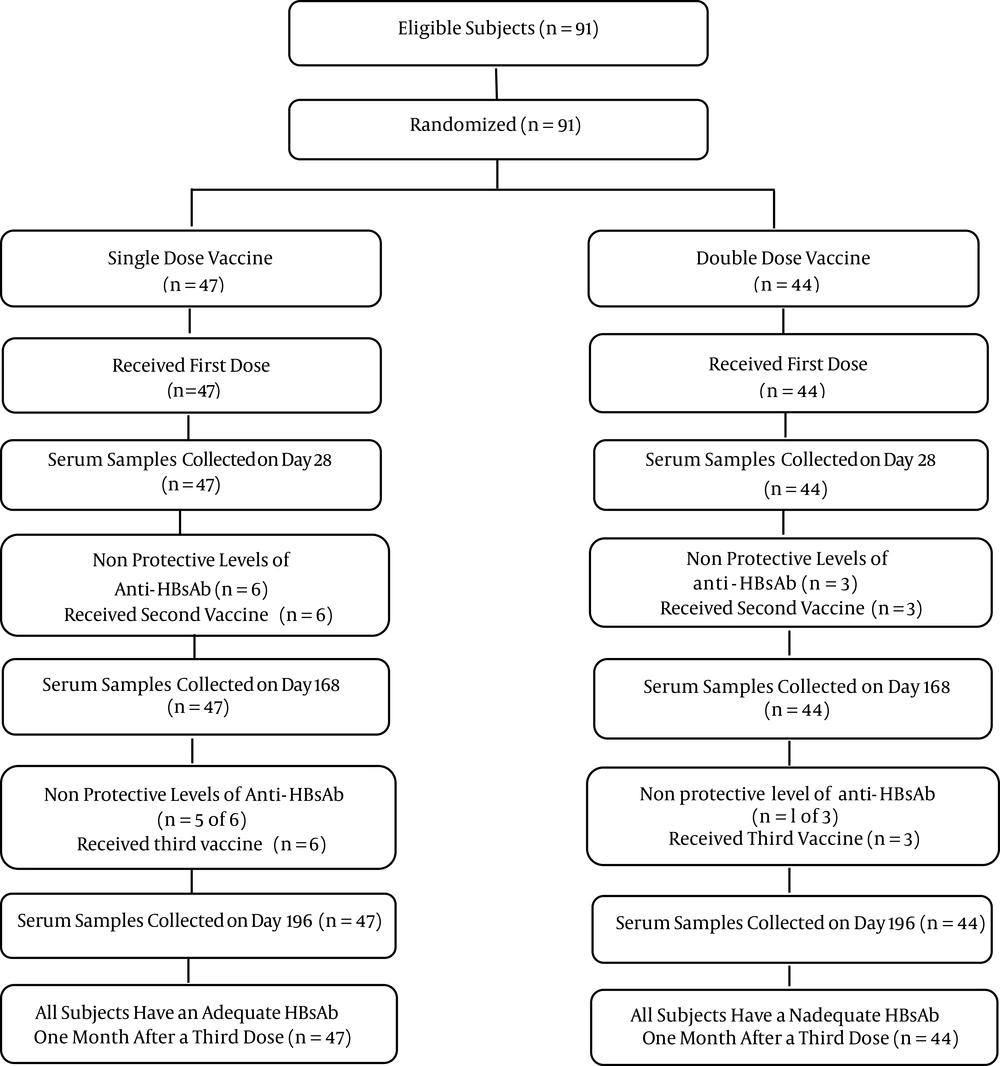

The consort diagram in Figure 1 illustrates the participants flow through each stage of the study. The baseline characteristics of the two groups, including age, gender and BMI are described in Table 1.

aIndependent t-test or chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests.

bValues are expressed as mean (SD).

In the groups that received single and double HB vaccines, robust antibody responses were elicited even after the first booster dose. One month after the first dose of vaccines, the rates of arbitrary seroprotection, defined as the presence of a hepatitis B surface antibody titer > 10 mIU/mL, in the single-dose and double-dose groups were 87.2% and 93.2%, respectively, and the difference was not significant (P = 0.64). Six months after the first vaccine dose (before the third dose), the rates of arbitrary seroprotection in the single-dose and double-dose groups were 89.6% and 97.8%, respectively, and the difference was not significant (P = 0.83). One month after the third vaccine dose, the rates of arbitrary seroprotection in both groups were 100% (Table 2).

| Anti-HBs Titers, mIU/mLb | Single-dosec | Double-dosed |

|---|---|---|

| One month after the first dose | ||

| > 200 | 31 (66.0) | 35 (79.5) |

| 100.1 - 200 | 3 (6.4) | 1 (2.3) |

| 10.1 – 100 | 7 (14.9) | 5 (11.4) |

| 0 - 10b | 6 (12.8) | 3 (6.8) |

| Six months after the first dose | ||

| > 200 | 31 (66.0) | 37 (84) |

| 100.1 - 200 | 4 (8.5) | 1 (2.3) |

| 10.1 - 100 | 7 (14.9) | 5 (11.4) |

| 0 - 10b | 5 (10.6) | 1 (2.2) |

| Seven months after the first dose | ||

| > 200 | 37 (78.7) | 38 (86.3) |

| 100.1 - 200 | 3 (6.3) | 1 (2.2) |

| 10.1 - 100 | 7 (15) | 5 (11.5) |

| 0 – 10b | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

bAnti-HBs titers ≤ 10 mIU/mL was defined as non-protective.

cForty-seven participated in single dose protocol.

dForty-four participated in double dose protocol.

The result of GEE analysis are shown in Table 3 ; there was no significant difference in seroprotection rates between the two groups.

| Parameters | Exp. β (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Group | 0.34 | |

| Single dose | 0.5 (0.11 - 2.13) | |

| Double dose | Ref. | |

| Month after the first dose | Not computed | |

| One | 1 | |

| Six | 1 | |

| Seven | Ref. |

5. Discussion

The recommendations to immunize HCWs against hepatitis B are well known. However, a proportion of individuals do not respond to the primary standard three-dose HB vaccination schedule at zero, one and six months after vaccination and remain susceptible to the infection. The response to HB vaccination is inversely correlated with age and weight (32, 33). Several methods are tested to overcome this non-responsiveness. The CDC recommends the consideration of revaccination for persons who do not respond to the primary vaccine series with > 1 booster vaccine dose (three total booster injections) (34, 35). For individuals with risk factors for nonresponse, a 40 µg dose of vaccine may be used (36, 37).

The present study evaluated the immunogenicity of a double-dose (40 µg) vaccine versus that of a single-dose vaccine (20 µg) in HCWs who exhibited no response to the primary schedule vaccine series. Considerable seroconversion rates were observed among the participants who received both the double- and single-dose vaccines, and the differences in the seroconversion rates between the two groups were not significant.

After the first booster dose of HB vaccine that contained 40 µg of the antigen, a seroconversion rate of 93.2% was observed, whereas 89.6% of the participants who received the HB vaccine containing 20 µg of antigen seroconverted; the difference was not significant. In agreement with the current study findings, Cardell et al. (29) reported that 59%, 80% and 95% of non-responders who received double-dose HB vaccine developed anti-HBs titers >10 mIU/mL after the first, second and the complete three-dose schedules, respectively.

However, other studies demonstrated that the rate of seroconversion following high-dose HB vaccination is significantly greater than that of following a low-dose vaccination (27, 29). The discrepancies in these studies may be due to differences in the participant characteristics and sample sizes. In the current study, the seroconversion rates were greater in the double-dose group than in the single-dose groups after the first and second injections, but the differences were not significant. Significant results might have been possibly obtained with a larger sample size. Finally, further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to clarify the small differences in the seroconversion rates following single- and double-dose HB vaccinations in HCWs who do not respond to the primary vaccine series.

A major limitation of the current study was the small sample sizes which might have led to the non-significant results. Another important limitation of the study was the lack of prior research studies on the topic. More research is needed about revaccination of non-responder HCWs.

In conclusion, the results of the current study demonstrated that both single- and double-dose HB vaccines are adequately immunogenic and the double-dose of HB vaccine (containing 40 µg of antigen) did not seem to be significantly more immunogenic in terms of the seroconversion rates than the single-dose vaccine (containing 20 µg of antigen) in HCWs not responding to the primary vaccine series.