1. Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related death globally (1). Sorafenib, a multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, remains the standard of care for patients with inoperable or advanced-stage HCC. In resource-limited settings without access to surgical or locoregional therapy, sorafenib may be the only option for treating HCC. However, due to a modest survival benefit, as well as the limiting cost of sorafenib in certain regions, appropriate selection of patients for treatment is essential. Evaluation of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) criteria in resource-limited settings is frequently unachievable due to a variety of reasons. Using a cohort from the South American liver research network (1336 HCC cases), we created a cost-effective prognostic scoring system to help identify patients likely to have a survival benefit on sorafenib treatment, using simple laboratory variables (2).

2. Methods

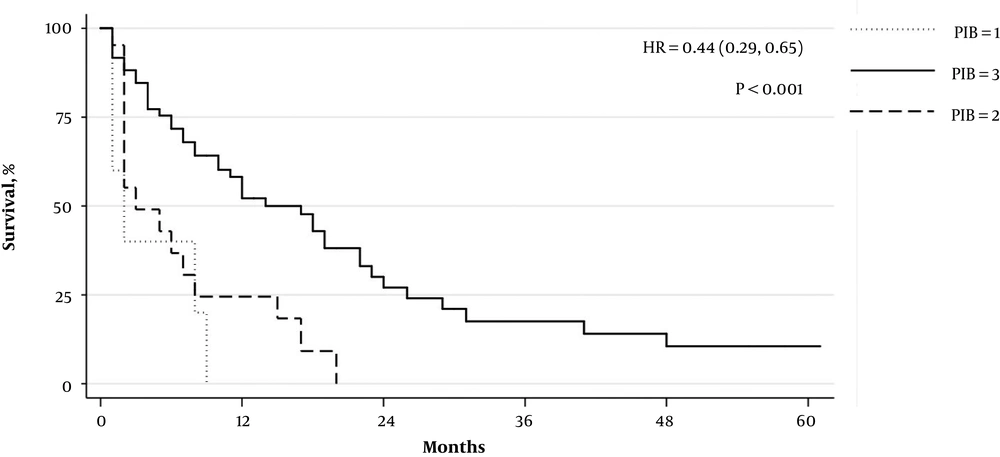

In order to design the Platelet-INR-Bilirubin (PIB) Score, we assigned each patient in the sorafenib cohort, with available laboratory and survival data, one point for each of the following: (1) total bilirubin ≤ 3.0 mg/dL, (2) platelets ≤ 250 × 109/L, (3) INR ≤ 1.6, following the methodology previously described by Di Constanzo et al. (3). Each of these variables showed a similar significant difference in predicting survival and therefore were chosen for this score. Our group previously identified these variables as prognostic factors for improved survival on sorafenib in a South American population (4). The PIB score has a hypothetical score range of 0 to 3. Measures of central tendency were expressed as medians (Q1 - Q3). Kaplan-Meyer survival curves were constructed to graphically compare scores. Hazard ratios were derived using Cox proportional hazard regression with the Breslow method for ties. The log-rank test was used to assess the equality of survivor functions. A level of evidence of P ≤ 0.05 was taken as the criterion for significance. A biostatistician was consulted for review of our data analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA V. 14.2 (Statacorp, College Station, TX). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Hennepin County Medical Center. In addition, each center was responsible for obtaining appropriate IRB approval.

3. Results

Of the total 1336 patients with HCC, 127 patients were treated with sorafenib. Of these, 86 had complete laboratory and survival data. Patient characteristics stratified by data completeness are available in Table 1. The median age of this sub-cohort was 64 years (IQR: 55 - 71) and 67% of subjects were male. Hepatitis C infection was the most common etiology of HCC (42%). Sixty-three patients (76%) died during the designated study period. The median survival time after initiation of sorafenib treatment was 7.5 months (IQR 2 - 17) in all subjects. There were no patients with a PIB score of “0”, five patients with a score of “1”, 21 patients with a score of “2” and 61 patients with a score of “3”. Patients with a PIB score of “1” or “2” had a median survival of 2 months (IQR 1 - 8 and 2 - 7, respectively). Patients with a PIB score of “3” had a median survival of 10.5 months (IQR 4 - 21). Increasing PIB score was significantly associated with improved survival (HR 0.44 [0.29, 0.65], P < 0.001). Kaplan-Meyer survival curves by score are displayed in Figure 1.

| Parameter | All Patients (n = 127) | Complete Survival Data (n = 86) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65 (55 - 71) | 64 (55 - 71) | 0.3 |

| Gender | 0.4 | ||

| Male | 70 (89/127) | 67 (58/86) | |

| Female | 30 (38/127) | 33 (28/86) | |

| Etiology of HCC | |||

| Infectious | 51 (65/127) | 54 (47/86) | 0.3 |

| HBV + | 15 (19/127) | 15 (12/86) | 0.8 |

| HCV + | 38 (48/127) | 42 (36/86) | 0.2 |

| ASH | 32 (41/127) | 36 (31/86) | 0.08 |

| NASH | 17 (21/127) | 10 (9/86) | 0.01 |

| BCLC stage | 0.6 | ||

| A/B | 31 (33/107) | 33 (28/86) | |

| B/C | 69 (74/107) | 67 (58/86) |

Patient Characteristics of Patients with HCC on Sorafeniba

4. Discussion

Our study describes a simple, cost-effective scoring system associated with improved survival in patients with HCC treated with sorafenib. While many new scoring systems are available for this purpose, they tend to include variables that are too financially prohibitive or too administratively cumbersome for under-staffed, resource-limited settings (3, 5, 6). Many physicians rely on BCLC staging to determine sorafenib eligibility, but as this clinical tool is dependent on advanced imaging modalities, its utility is severely limited. Moreover, as HCC in areas such as Africa is generally treated by oncologists rather than hepatologists, addressing BCLC criteria represents an additional burden. Other prognostic scores include sorafenib-associated side effects, making them useful for decision-making related to continuing therapy, but unhelpful for determining which patients should receive initial treatment (3).

Due to the retrospective design, data completeness limited the size of the cohort used to design the PIB score. However, groups stratified by data completeness were similar with regards to baseline characteristics, with the exception of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) status, which was less common in patients whose data was used to make the PIB score. As NASH status was not a statistically significant factor associated with survival in our previous analysis, we do not feel that this impacts the reliability of the PIB score (2).

The simplicity and affordability of using the PIB score makes it useful in developing settings with limited access to laboratory and imaging resources. Further validation in a larger prospective study will be of benefit.