1. Context

Co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) is known as a significant threat to public health (1, 2). Worldwide, approximately 71 million people have chronic HCV infection that 2.3 to 5 million individuals have HIV/HCV co-infection (3-5). The national survey in Iran has estimated HCV infection affects 0.3% of the overall population which 11% of them have HIV/HCV co-infection (6). Besides, HIV/HCV co-infection accelerates liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and leads to a higher rate of liver decompensation (7-9).

In the era of various and effective treatments for HCV, although the treatment-induced clearance of HCV improves survival of patients with HIV/HCV co-infection, a considerable number of them continue to exist untreated due to the problem with access to HCV treatments (10-12). Meanwhile, comorbid conditions like psychiatric problems, substance abuse, and drugs interactions can reduce the uptake of HCV antiviral therapy among patients with HIV/HCV co-infection (13).

In the past decades, although adding ribavirin (RBV) to pegylated-IFN lead to improvement in efficiency of patients’ treatment, dissatisfied results were described in patients with HIV/HCV co-infection (14, 15). The new generation of DAAs caused improvement in the effectiveness of antiviral therapies and reduced drugs complications in HIV/HCV co-infected patients without consideration of liver fibrosis or treatment history (16-19). Accordingly, HIV guidelines have recommended anti-retroviral therapy (ART) for patients with HIV/HCV co-infection simultaneously with the HCV DAAs as supplementation (11, 20).

2. Objectives

The primary objective of this systematic review was determination of the effectiveness of HCV IFN-free DAA-containing regimens in patients with HIV/HCV co-infection.

3. Evidence Acquisition

3.1. Data Resources and Search Strategies

All steps of this systematic review were based on the PRISMA guideline for reporting systematic review (21). According to the subject of this study, we selected some appropriate keywords to be searched in the different databases. They were “simeprevir”, “grazoprevir”, “paritaprevir”, “daclatasvir”, “asunaprevir”, “ledipasvir”, “elbasvir”, “sofosbuvir”, “ombitasvir”, “dasabuvir”, “velpatasvir”, “direct-acting antiviral”, “HIV”, “human immunodeficiency virus” AND “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome”. Using these keywords, we created a specific search strategy for different databases including PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science. Our last search was performed on 5 May, 2017. Furthermore, we used a different combination of these keywords in Google Scholar to check if we missed any related articles. This approach also helped us to evaluate the sensitivity of our search formulas. For this purpose, we screened titles of articles in Google scholar until we found 20 unrelated serial titles. After all, we checked the references of all finally included studies in our project to find any possible missed articles.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

We included all studies investigating the effectiveness of HCV IFN-free treatments with DAAs (sofosbuvir, daclatasvir, ledipasvir, ombitasvir, paritaprevir, asunaprevir, dasabuvir, grazoprevir, elbasvir, velpatasvir or simeprevir) among HIV/HCV co-infected patients. Treatment effectiveness was determined using the sustained virologic response (SVR) as having undetectable HCV RNA, 12 weeks after the end of treatment. We decided to consider only cohort or clinical trial studies published in peer-reviewed journals, and in the English language for inclusion in our study. Those studies which evaluated the effectiveness of regimens containing telaprevir and boceprevir or studies with a sample size of fewer than five patients were excluded from our systematic review.

3.3. Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Presentation

All articles through searching databases were imported to the EndNote Software. Two investigators (SMT and FD) independently screened titles, abstracts, and full-texts of articles, respectively and according to the selection criteria. Investigators resolved any disagreement by mutual discussion or consultation with other authors (HSH and SMA).

The same two investigators extracted the following data from each study or each appropriate treatment protocol of study: Name of the first author, publication year, sample size, HCV genotype, treatment protocol including type and number of DAAs or using RBV, duration of the treatment protocol, and the rate of SVR. For evaluating each included clinical trial, Cochrane’s assessment tool was used (22). This assessment tool contains 12 items that overall score ≥ 6 was considered as low risk for each study. For assessing the included non-randomized studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) was used (23).

Included studies had a wide variation in their methodology, and we could not run meta-analysis. Therefore, we just decided to gather their relevant information and present them in a table which tries to put together different studies with the same treatment regimens.

4. Results

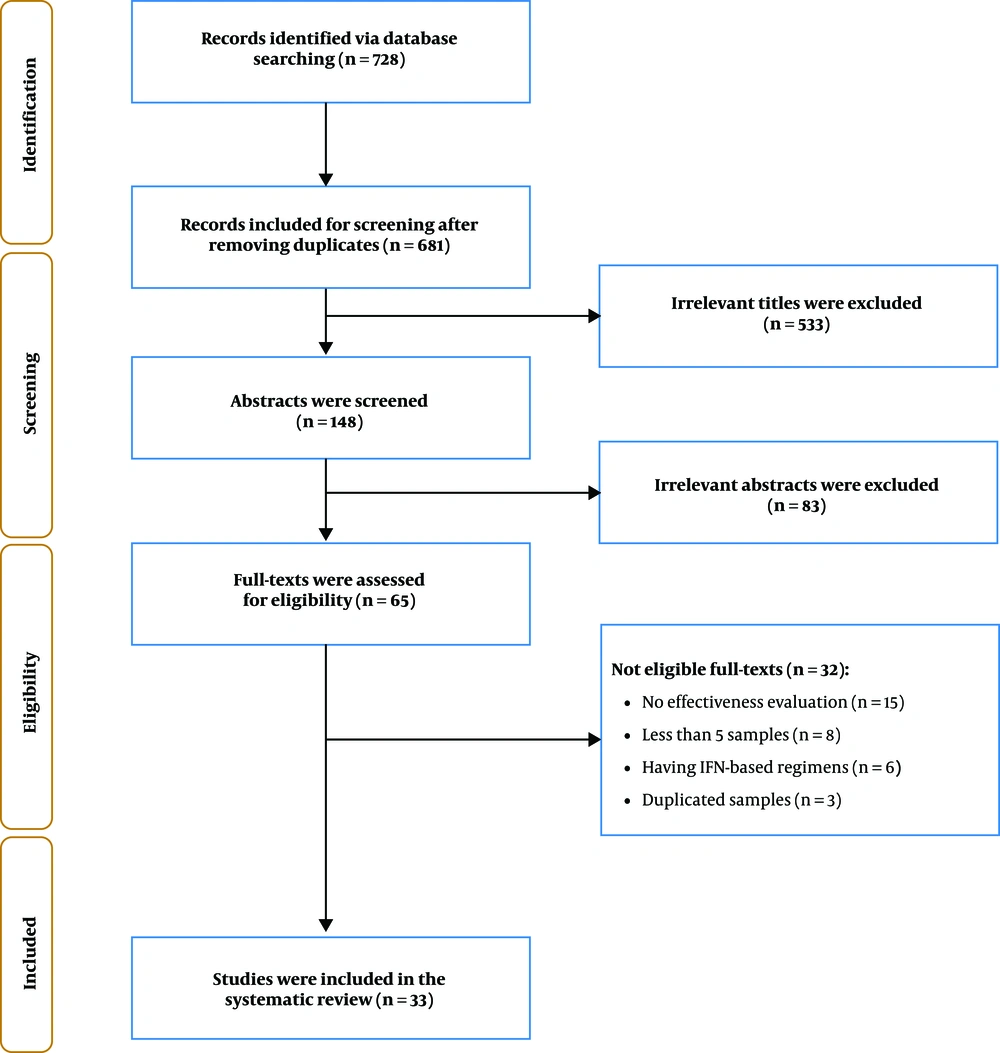

A total of 681 papers were found through database searching after removing duplications. In title screening, 533 irrelevant titles and in abstract screening, 83 irrelevant abstracts were excluded. Then, 65 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and finally, 33 articles included in our study (Figure 1).

Finally, in this study, seven different regimens were evaluated. Ten studies assessed sofosbuvir (SOF) plus simeprevir (SMV) regimen that the lowest SVR was 72.7% and the highest was 100%. Nine studies evaluated SOF plus RBV regimen, and SVR ranged between 51.6% and 91.6%. In the assessment of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (SOF/LDV) combination, 12 studies were examined that the SVR rate was from 88.8% to 100%. Eight studies evaluated SOF plus daclatasvir (DCV) regimen, and SVR ranged between 84.6% and 100%. Grazoprevir/elbasvir (GZR/EBR) combination was the fifth regimen included in our study. In the assessment of this regimen, two studies were evaluated in which the lowest SVR was 86.6%, and the highest SVR was 96.5%. In the investigation of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir (OBV/PTV-r) plus dasabuvir (DSV) combination, six studies were assessed. The maximum and minimum SVR rate was 100% and 90.6%, respectively. The seventh regimen was the combination of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (SOF/VEL) in which only one study was evaluated, and the SVR was 95.2%. Table 1 shows the important characteristics of the included studies and also the response rate to each HCV antiviral regimen.

| Regimen/Author | Year | Sample Size | Duration (Week) | HCV Genotype | Ribavirin | SVR Protocol | SVR12, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sofosbuvir plus simeprevir | |||||||

| Del Bello et al. (24) | 2016 | 41 | 12 | 1 | No | ITT | 75.6 |

| Del Bello et al. (24) | 2016 | 17 | 12 | 1 | Yes | ITT | 94.1 |

| Johnson et al. (25) | 2016 | 13 | 12 | 1 | No | ITT | 92.3 |

| Grant et al. (26) | 2016 | 6 | 12 | 1 | No | PP | 100 |

| Hawkins et al. (27) | 2016 | 33 | 12 | ND | No | PP | 96.9 |

| Merli et al. (28) | 2016 | 12 | 12 | 1a, 1b, 4 | Mix | ITT | 100 |

| Milazzo et al. (29) | 2016 | 11 | ND | 1a, 1b, 4 | Mix | ITT | 72.7 |

| Patel et al. (13) | 2016 | 17 | 12 | ND | No | ITT | 100 |

| Bruno et al. (30) | 2017 | 29 | 12 | 1a, 1b, 4 | Mix | ITT | 86.2 |

| Montes et al. (31) | 2017 | 23 | ND | 1a, 1b, 4, Mix/Other | Mix | ITT | 82.6 |

| Piroth et al. (32) | 2016 | 19 | 12, 24 | 1, 4 | Mix | ITT | 89.4 |

| Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin | |||||||

| Del Bello et al. (24) | 2016 | 31 | 12 | 1 | Yes | ITT | 51.6 |

| Campos-Varela et al. (33) | 2016 | 10 | 24 | ND | Yes | PP | 80 |

| Grant et al. (26) | 2016 | 7 | 12 | ND | Yes | PP | 57.1 |

| Molina et al. (34) | 2013 | 274 | 24 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Yes | ITT | 86.4 |

| Younossi et al. (35) | 2015 | 497 | 12, 24 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Yes | ITT | 83 |

| Sulkowski et al. (36) | 2014 | 223 | 12, 24 | 1a, 1b, 2, 3 | Yes | ITT | 78.9 |

| El Sayed et al. (37) | 2017 | 12 | 12 | 1a,1b | Yes | ITT | 91.6 |

| Patel et al. (13) | 2016 | 7 | 12 | ND | Yes | ITT | 85.7 |

| Piroth et al. (32) | 2016 | 51 | 12, 24 | 2, 3 | Yes | ITT | 86.2 |

| Sofosbuvir/ledipasvir | |||||||

| Johnson et al. (25) | 2016 | 15 | 12 | 1 | No | ITT | 100 |

| Cooper et al. (38) | 2016 | 9 | 24 | 1a, 1b | Yes | ITT | 88.8 |

| Grant et al. (26) | 2016 | 11 | 12 | ND | No | PP | 100 |

| Naggie et al. (16) | 2015 | 335 | 12 | 1a, 1b, 4 | No | ITT | 96.1 |

| Osinusi et al. (39) | 2015 | 50 | 12 | 1a, 1b | No | ITT | 98 |

| Younossi et al. (40) | 2016 | 335 | 12 | 1, 4 | No | ITT | 96.1 |

| Ingiliz et al. (41) | 2016 | 28 | 8 | 1, 4 | No | PP | 96.4 |

| Steiner et al. (42) | 2016 | 19 | 12, 24 | 1, 3 | No | PP | 100 |

| Bhattacharya et al. (43) | 2017 | 119 | 12 | 1 | Yes | PP | 90.7 |

| Bhattacharya et al. (43) | 2017 | 569 | 12 | 1 | No | PP | 95.2 |

| Patel et al. (13) | 2016 | 137 | 12 | ND | No | ITT | 98.5 |

| Montes et al. (31) | 2017 | 288 | ND | 1a, 1b, 4, Mix/Other | Mix | ITT | 93.7 |

| Piroth et al. (32) | 2016 | 56 | 12, 24 | 1, 4, 6 | No | ITT | 96.4 |

| Piroth et al. (32) | 2016 | 10 | 12, 24 | 1, 4, 6 | Yes | ITT | 96.2 |

| Sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir | |||||||

| Luetkemeyer et al. (44) | 2016 | 151 | 12 | 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4 | No | PP | 97.3 |

| Mandorfer et al. (45) | 2016 | 31 | 12, 24 | 1, 3, 4 | No | ITT | 100 |

| Wyles et al. (46) | 2015 | 203 | 8, 12 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | No | ITT | 92.1 |

| Castells et al. (47) | 2017 | 6 | 24 | 1a, 1b, 2, 3 | No | ITT | 100 |

| Milazzo et al. (29) | 2016 | 18 | ND | 1a, 1b, 3, 4 | Mix | ITT | 100 |

| Rockstroh et al. (48) | 2017 | 39 | 24 | 1a, 1b, 3, 4, Mix | No | ITT | 84.6 |

| Rockstroh et al. (48) | 2017 | 16 | 24 | 1a, 1b, 3, Mix, Unknown | Yes | ITT | 93.7 |

| Montes et al. (31) | 2017 | 74 | ND | 1a, 1b, 3, 4, Mix/Other | Mix | ITT | 93.2 |

| Piroth et al. (32) | 2016 | 156 | 12, 24 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 | No | ITT | 95.5 |

| Piroth et al. (32) | 2016 | 25 | 12, 24 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 | Yes | ITT | 92 |

| Grazoprevir/Elbasvir | |||||||

| Rockstroh et al. (17) | 2015 | 218 | 12 | 1a, 1b, 4, 6 | No | ITT | 96.3 |

| Sulkowski et al. (49) | 2015 | 30 | 12 | 1a, 1b | No | ITT | 86.6 |

| Sulkowski et al. (49) | 2015 | 29 | 12 | 1a, 1b | Yes | ITT | 96.5 |

| Ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir | |||||||

| Sulkowski et al. (2) | 2015 | 31 | 12 | 1 | Yes | ITT | 93.5 |

| Sulkowski et al. (2) | 2015 | 32 | 24 | 1 | Yes | ITT | 90.6 |

| Bhattacharya et al. (43) | 2017 | 55 | 12 | 1 | Yes | PP | 90.9 |

| Bhattacharya et al. (43) | 2017 | 23 | 12 | 1 | No | PP | 95.6 |

| Milazzo et al. (29) | 2016 | 22 | ND | 1a, 1b | Mix | ITT | 90.9 |

| Wyles et al. (58) | 2017 | 22 | 12 | 1 | Yes | ITT | 100 |

| Montes et al. (31) | 2017 | 88 | ND | 1a, 1b, Mix/Other | Mix | ITT | 98.8 |

| Massimo et al. (50) | 2016 | 210 | 12, 24 | 1 | Mix | ITT | 96.6 |

| Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir | |||||||

| Younossi et al. (51) | 2017 | 106 | 12 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | No | ITT | 95.2 |

5. Discussion

5.1. Sofosbuvir Plus Simeprevir

Although no dose adjustment is required in patients with renal impairment, SMV cannot be used in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and patients with previous episodes of decompensation. This antiviral agent is available as capsules containing 150 mg of SMV and taken one capsule once daily with food. In patients receiving SMV, some antiretroviral agents are contraindicated, including cobicistat-based regimens, efavirenz, etravirine, nevirapine, ritonavir, and any HIV protease inhibitor, boosted or not by ritonavir. In the recent EASL guideline, SMV-containing regimens are not recommended but based on 2016 version of this guideline, a combination of SOF plus SMV is appropriate just for genotype 4 in HCV mono-infected or HIV/HCV co-infected patients without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis (52-54).

The most of studies found high response rate treating patients with SOF plus SMV. However, the study by Milazzo et al. found a suboptimal response rate which may be caused by HCV gene polymorphisms in NS3 (Q80K and S122T) that detected in sequencing analysis (29).

5.2. Sofosbuvir Plus Ribavirin

Sofosbuvir is an HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor that suppresses HCV replication and life cycle. Sofosbuvir is available at the dose of 400 mg (one tablet) and consumed once per day. There are no potential drug-drug interactions between SOF and antiretroviral drugs but in patients with severe renal impairment is contraindicated (53, 55). Combination of SOF plus RBV as an independent regimen for treatment of HCV infection was available in previous EASL guideline, but in 2018 version, this regimen is not available. However, none of these guidelines suggested this combination for patients with HIV/HCV co-infection (53, 54). Meanwhile, based on study assessments, this combination could not achieve acceptable SVR. The study by Del Bello et al., which was performed on patients with genotype-1 HCV, reported the lowest SVR rate (51.6%); most patients in this study were cirrhotic with a history of interferon treatment (24). In another study by Hawkins et al., the SVR rate was nearly 57.1%; most patients in this study were treatment experienced and suffered from cirrhosis (27). Seemingly, the SOF plus RBV combination is not effective in the treatment of patients with HCV infection. The SVR rate did not increase even after elongating the treatment duration.

5.3. Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir

This regimen as a combination of 400 mg SOF and 90 mg LDV in a single tablet is available. There was no difference in LDV plasma exposure (area under the curve (AUC)) between patients with severe hepatic impairment and normal ones. Based on the pharmacokinetic analysis in HCV-infected population, cirrhosis (compensated and decompensated) cannot cause a clinically relevant effect on the exposure to LDV. This regimen can be used in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment without dose adjustment, but the safety of the SOF/LDV combination has not been assessed in patients with severe renal impairment (53, 56). The SOF/LDV combination may be considered an effective regimen for patients with HCV mono-infection or HIV/HCV co-infection (16, 57).

Almost all antiretroviral agents may be given with this regimen. However, some combinations should be used with caution, with frequent renal monitoring due to an increase in tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) concentrations especially when ritonavir or cobicistat as pharmacokinetic enhancer are present in an antiretroviral regimen. These combinations include atazanavir/cobicistat, atazanavir/ritonavir, elvitegravir/cobicistat, darunavir/ritonavir, lopinavir/ritonavir, darunavir/cobicistat and all in combination with TDF/emtricitabine. Fortunately, after approval of the tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF), due to lower plasma tenofovir levels, concerns about an interaction leading to increased tenofovir exposure have been diminished.

5.4. Sofosbuvir Plus Daclatasvir

Based on 2016 EASL guideline, this combination as a pangenotypic regimen was recommended for treatment of chronic HCV infection even in HIV co-infected and cirrhotic patients. Nevertheless, in the last version of EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C, there is not any DCV-containing regimen. Daclatasvir is available in 30 mg and 60 mg tablets. Dose adjustment of DCV is not required for patients with renal and hepatic impairment. The assessment of drug interactions with antiretroviral agents demonstrated that there is no absolute contraindication between these drugs and DCV, but dose adjustment is required in some cases. A daily dose of DCV should be adjusted to 30 mg with atazanavir/ritonavir and cobicistat-containing antiretroviral regimens and increase to 90 mg per day with efavirenz (an enzyme inducer). Also, using etravirine and nevirapine, both enzyme inducers, with DCV containing regimen are not recommended, and it may require a dosage adjustment, altered timing of administration or additional monitoring (53, 54). As shown in Table 1 the SVR rate in patients receiving SOF plus DCV is remarkable.

5.5. Grazoprevir/Elbasvir

GZR/EBR with or without RBV had few side effects so that less than 1% of patients treated with this regimen discontinued treatment due to adverse events. There is a contraindication for GZR/EBR in patients with moderate and severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh B and C), but dose adjustment is not required in patients suffering from renal impairment. Based on the EASL guideline, there are limitations on consuming GZR/EBR with antiretroviral agents. The nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors can be used and no clinically significant interaction expected. This group of ARTs includes abacavir, lamivudine, tenofovir (either as TDF or as TAF), emtricitabine, rilpivirine, raltegravir, dolutegravir and maraviroc (53).

In the evaluation of this treatment regimen, only two studies were examined. It can be seen from the data in Table 1 that this regimen obtained relatively acceptable results.

5.6. Ombitasvir/Paritaprevir/Ritonavir Plus Dasabuvir

This regimen can be used in patients suffering mild hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh A) without a dose modification, but the combination of ritonavir-boosted PTV and OBV with or without DSV should not be used in patients with moderate and severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh B and C). In HIV co-infected patients drug interactions need to be carefully considered. From protease inhibitors, only atazanavir and darunavir can be taken without ritonavir, and the rest of protease inhibitors are contraindicated. Efavirenz, etravirine, and nevirapine are contraindicated. ECG monitoring should be considered in case of prescribing rilpivirine. Due to additional boosting effect, cobicistat-containing regimens should not be used. Based on EASL treatment recommendation for chronic hepatitis C, in HCV mono-infected or HIV/HCV co-infected patients without cirrhosis or with compensated (Child-Pugh A) cirrhosis, this regimen can be used only in genotype 1b (53, 58-61). As can be seen from Table 1 the most of studies found high response rate while treating patients with this regimen.

5.7. Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir

In HIV/HCV co-infected patients, SOF/VEL can be used along with most of the antiretroviral agents, the exceptions being the inducing drugs efavirenz, etravirine, and nevirapine. VEL exposure would decrease by about 50% if efavirenz consumed concurrently. Secondary to inhibiting P-gp by SOF/VEL exposure of tenofovir increases so renal adverse events should have been monitored in patients on a regimen containing TDF. This regimen can be used for all HCV genotypes in non-cirrhotic patients but in patients with compensated (Child-Pugh A) cirrhosis, SOF/VEL is not recommended for HCV genotype 3. SOF/VEL, with daily weight-based RBV (all genotypes) can be used in patients with decompensated (Child-Pugh B or C) cirrhosis (with no evidence of HCC) that are not on the waiting list for liver transplant and in patients waiting for liver transplantation with MELD score < 18 - 20 (53, 62-64). In the evaluation of this treatment regimen, only one study was assessed. In the study by Younossi et al., patients received 400 mg of SOF and 100 mg of VEL in a single tablet. The SVR rate was 95.2% in 106 patients with different HCV genotypes, who received 12 weeks of treatment (51).

6. Conclusions

With more than 70 million worldwide prevalence, hepatitis C is raised as a global concern (65). 20% SVR was the result of HCV treatment with pegylated-interferon and adding RBV increased the treatment efficacy by up to 50% (66, 67).

Introduction of first DAAs in 2011 was one of the most significant recent achievements in the field of hepatology and liver diseases makes hepatitis C a curable disease (68, 69). The emergence of the new generation of DAA agents led to creating IFN-free regimens with more than 95% efficacy (70-72). Therefore, treatment of HCV patients seems to be available.

These days, treatment of special patient populations functions as a challenge to HCV treatment. Patients co-infected with HIV are one of these particular groups that need special attention because it is widespread, particularly among people who inject drug, and they exhibit lower rates of spontaneous HCV clearance. On the other hand, HIV/HCV patients are prone to HCV-related liver diseases such as cirrhosis and HCC and historically had lower SVR rate during chronic HCV treatment than mono-infected patients (73).

As treatment of HCV improved after approval of new all-oral regimens of DAAs, the efficacy and safety of HIV/HCV co-infected patients’ treatment had also been dramatically improved (39, 74). It is also noted in the HIV guidelines that treatment of HIV/HCV patients completed by the combination of ARTs and DAAs and only point in this area is drug interactions (20, 75).

The result of our systematic review demonstrated that an IFN-free regimen that contains the new generation of DAA agents could provide a high SVR rate. So identifying these patients and choosing appropriate treatment will lead to satisfactory therapeutic results. On the other hand, health policymakers should design screening programs to identify patients with HIV/HCV co-infection and make the new HCV medicines available at affordable prices.