1. Background

Chronic liver disease (CLD) is a global problem that is related to considerable economic encumbrance (1). It is ascribed to 1.16 million deaths each year, which is around 3.5% of all deaths worldwide, making it the 11th, 10th and 8th leading cause of mortality globally, in South Asia and the Middle East, respectively (2). It has the highest rate of inpatient mortality among all hospital admissions for gastrointestinal and liver disease patients (3).

Chronic illnesses are liable for long-term hassles and burdens, and in recent years, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) has now become a matter of prodigious concern. Being a chronic disease, CLD substantially reduces HRQoL (4). Chronic liver disease comes in the top 20 causes of global morbidity (5). South-East Asia carries the maximum burden of CLD, with the highest calculated disease-related disability-adjusted life years (DALY) and years of life lost (YLL) (6).

An additional trait of chronic illnesses is not only the patient’s quality of life but also the monetary burden imposed on the patient and the whole family unit altogether. Pakistan has been classified under the group of lower-middle-income economic countries by the World Bank with gross national income (GNI) per capita of 1580 United States Dollars (USD) (7, 8). Liver diseases are the cause of significant burden and cost. Moreover, inpatient health care utilization has increased for patients with CLD during the last couple of decades (3). The overall cost of CLD takes into account the direct cost (including medications and hospital admissions) and unforeseen costs (owing to loss of work efficiency and drop in HRQoL) (1). In the United States, the approximate direct and indirect cost of CLD in 2004 was 2.5 billion USD and 10.6 billion USD, respectively (9). Analysis of data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS; 2004 - 2013) showed that annual health expenditures were higher in CLD patients (USD 19,390 vs. USD 5,567 in non-CLD patients) (10). Though we don’t have exact data for Pakistan, it is expected to be worse in our poor socioeconomic conditions.

In 2005, it was projected that without rigorous preventive and control action, chronic illnesses might cause 36 million deaths in the next 10 years. The majority of these preventable deaths will be in low to middle-income populations, with half of them having age under 70 years (11). Furthermore, the poorest individuals are most vulnerable to the development of chronic ailments, and this population is unable to handle the consequential financial impacts (12). Therefore because of the fairly higher prevalence of chronic disorders in the lower socioeconomic group, we looked into the economic stress faced by the patients and their families in the context of their disease and their employment status following the diagnosis and management of their CLD.

2. Objectives

The study was carried out with the objective of exploring the economic burden in CLD patients, with the principal hypothesis being that persons with longer-lasting and severe disease would have direr financial problems.

3. Methods

This was a cross-sectional, observational study wherein patients suffering from CLD were enrolled from the gastroenterology clinics at the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH), Karachi, Pakistan. The AKUH is one of the largest hospitals in the country with a large catchment area (both urban and rural areas) and catering diversity of patients who belong to every group of socioeconomic status. Around 6,000 to 8,000, new patients are seen in the AKUH gastroenterology clinics every year. Nearly half of them present for liver diseases, of which hepatitis B and hepatitis C makes three quarters (13).

All CLD patients between ages 18 to 80 years, presented to the clinic from January to December 2016 were approached, and those who consented were assessed using two validated questionnaires.

Exclusion criteria included patients suffering from acute viral hepatitis, chronic viral hepatitis without advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis, other chronic conditions that could have influenced the quality of life and could put a burden on finances, including Inflammatory rheumatic conditions (such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis), severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, decompensated heart failure, obesity, vertebral fractures, solid organ transplant, chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis, irritable bowel syndrome, and a history of cancer (including hepatocellular carcinoma).

The patient’s demographic and disease-related information was collected via a preset form for meticulous assessment of their CLD (including the cause of liver disease, duration of liver disease, decompensation of CLD such as encephalopathy, ascites, jaundice, variceal bleeding, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatorenal syndrome, as well as Child Turcotte Pugh (CTP) and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores, etc.). A CTP score of 3 to 6 was categorized as CTP class A, 7 to 9 as CTP B, and 10 to 15 as CTP C (14, 15).

The interview was conducted by a dedicated research officer and a medical student. The McArthur Social Status questionnaire was administered to all patients to inquire regarding their educational status, social class, and financial condition. The questionnaire is well validated in previous studies for the determination of subjective social status (16-18). An additional set of questions was used to enlist the economic and occupational problems confronted by the patients owing to their illness. From these two questionnaires, we tried to estimate the economic encumbrance that the CLD had put on them and their relatives and how it affected their employment status.

Variables analyzed included age, gender, etiology of liver disease, the severity of CLD (as defined by CTP and MELD scores), duration of CLD (years), number of family members, number of family members aged > 18 years, maximum number of the years of education, highest educational degree, and current monthly income in Pakistani rupee (1 USD = 135 PKR). Outcomes of interest were self-perceived social and economic status, self-perception of disease responsibility for worsening of the social and economic situation, the impact of the disease on economic status due to medical expense, the impact of economic status on treatment compliance due to medical expenses, impact of severity of disease on socioeconomic status and treatment compliance, and impact of gender on disease status and treatment compliance.

The study was conducted following approval from the ethical review committee of The Aga Khan University Hospital. Informed consent was provided by the patients/caregivers before the administration of research questionnaires after explaining the nature of the information required. The questionnaires were introverted, and the participants were excluded from the research in the event that any of the subjects showed uneasiness in providing private information, such as their monetary and emotional strains. Moreover, complete privacy and confidentiality were ensured. There was no funding associated with this work.

3.1. Patient and Public Involvement Statement

We did not involve patients or the public in our work.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was done in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows (version 20). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD, and categorical variables are presented as frequency and percentages. To determine the impact of gender on disease and treatment, continuous variables between groups were compared by using unpaired t-test, and categorical variables were compared by using the chi-square test. All P values were two-sided, and a P value of < 0.05 was taken as significant.

4. Results

Out of 190 CLD patients enrolled, 127 (67.2%) were males. The mean age of our patients was 50.09 ± 12.05 years. The predominant etiologies of CLD were hepatitis C (70.5%) followed by Hepatitis B (HBV) and Hepatitis D (HDV). Half of the patients were CTP class B. Diabetes and hypertension were the major comorbid conditions present in 44 (25.6%) & 35 (18.5%) of the patients, respectively. The majority of patients (94%) belonged to the lower or middle-class social status (Table 1). Only one-fourth of the patients were educated up to a bachelor's degree or above. More than half of the subjects were unable to sustain their present standard of living for even a month, while two-thirds of the patients did not have enough savings to retain their existing standard of living even for three months if their source of income vanishes out. Table 1 describes the basic demographic features of the patients.

| Variables | Valuesa | Variables | Valuesa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 50.09 ± 12.05 | Current monthly income in Pakistani rupee (1 USD = 135 PKR) | |

| Gender | < 5 K | 10 (5.2) | |

| Male | 127 (67.2) | 5 - 10 K | 4 (2.1) |

| Female | 63 (32.8) | 10 - 15 K | 12 (6.3) |

| Etiology | 15 - 20 K | 10 (5.2) | |

| Hepatitis C | 134 (70.5) | 20 - 25 K | 4 (2.1) |

| Hepatitis B | 14 (7.3) | 25 - 50 K | 27 (14.2) |

| Hepatitis B + D | 25 (13.1) | 50 - 100 K | 29 (15.2) |

| Hepatitis B + C | 2 (1.1) | 100 - 500 K | 29 (15.2) |

| Alcohol | 4 (2.3) | > 500 K | 17 (8.9) |

| Non-B, Non-C | 11 (5.7) | Unsure | 48 (25.2) |

| CTP Class | Self-perceived socioeconomic status | ||

| A | 65 (34.2) | At the very top | 9 (4.7) |

| B | 97 (51.1) | Somewhere at the top | 9 (4.7) |

| C | 28 (14.7) | In the middle | 97 (51.1) |

| MELD score | 11.13 ± 3.9 | Somewhere at the bottom | 63 (33.2) |

| Duration of CLD (years) | 7.81 ± 6.161 | At the very bottom | 12 (6.3) |

| No of family members | 8.98 ± 7.562 | Maintenance of current standard of living with savings in hand, in the absence of any source of income | |

| No of family members age > 18 years | 5.23 ± 3.714 | < 1 month | 106 (55.7) |

| Max no. of the years of education | 8.88 ± 5.571 | 1 - 3 months | 49 (25.7) |

| Highest educational degree | 3 - 6 months | 21 (11) | |

| Illiterate | 28 (14.7) | 7 - 12 months | 4 (2.1) |

| Primary | 37 (19.4) | > 12 months | 10 (5.2) |

| Middle | 13 (6.8) | ||

| Matric | 28 (14.7) | ||

| Intermediate | 39 (20.5) | ||

| Bachelor’s | 32 (16.8) | ||

| Master’s | 11 (5.7) | ||

| Ph.D. | 2 (1) |

Demographics

Regardless of the disease duration, CLD significantly impacted a patient’s life, as 81% and 69% of patients blamed their disease responsible for deteriorating their social and financial state, respectively. Of the patients, 85% had consumed all their savings during their course of illness, and 67% of patients required borrowing money for their medical expenditures. Nearly half of the patients had to defer their children’s education. Around one-third of patients had unpaid medical and utility bills, or even skipped their meals. Worst of all, 14% of patients had to leave their houses in a quest for cheaper residence, and one out of every 10 had reached the limit of mortgaging their houses (Table 2).

| CTP A, N = 65 (34.3) | CTP B, N = 97 (51) | CTP C, N = 28 (14.7) | P Value | MELD Score | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worsening social status due to liver disease | Yes: 154 (81) | 47 (72.3) | 86 (88.7) | 21 (75) | 0.053 | 11.46 ± 4.06 | 0.077 |

| No: 36 (19) | 18 (27.7) | 9 (9.3) | 7 (25) | 10.09 ± 2.99 | |||

| Worsening economic status due to liver disease | Yes: 131 (69) | 26 (40) | 80 (82.5) | 25 (89.3) | 0.003b | 11.26 ± 4.24 | 0.572 |

| No: 59 (31) | 39 (60) | 17 (17.5) | 3 (10.7) | 10.95 ± 2.39 | |||

| Stopped saving | Yes: 132 (69.5) | 33 (50.7) | 74 (76.2) | 25 (89.3) | 0.001b | 11.64 ± 4.29 | 0.005b |

| No: 58 (30.5) | 32 (49.3) | 23 (23.8) | 3 (10.7) | 10.04 ± 2.61 | |||

| Utilization of previous savings | Yes: 162 (85.3) | 57 (87.6) | 79 (81.4) | 26 (92.8) | 0.347 | 11.52 ± 3.96 | 0.016b |

| No: 28 (14.7) | 8 (12.4) | 18 (18.6) | 2 (7.2) | 9.46 ± 3.03 | |||

| Need to borrow money for expenses | Yes 127 (66.9) | 37 (57) | 70 (72.2) | 20 (71.4) | 0.119 | 11.60 ± 4.00 | 0.074 |

| No: 63 (33.1) | 28 (43) | 27 (27.8) | 8 (28.6) | 10.43 ± 3.58 | |||

| House mortgage | Yes: 20 (10.5) | 5 (7.7) | 14 (14.5) | 1 (3.6) | 0.304 | 13.25 ± 5.14 | 0.026b |

| No: 170 (89.5) | 60 (92.3) | 83 (85.5) | 27 (96.4) | 10.97 ± 3.69 | |||

| Increasing loans | Yes: 111 (58.4) | 31 (47.6) | 63 (65) | 17 (60.7) | 0.115 | 11.77 ± 4.13 | 0.03b |

| No: 79 (41.6) | 34 (52.3) | 34 (35) | 11 (39.3) | 10.40 ± 3.44 | |||

| Delay in loan repayment | Yes: 77 (40.5) | 18 (27.7) | 49 (50.5) | 10 (35.7) | 0.05b | 11.41 ± 4.15 | 0.5 |

| No: 113 (59.5) | 47 (72.3) | 48 (49.5) | 18 (64.2) | 10.98 ± 3.75 | |||

| Delay in children’s education | Yes: 86 (45.3) | 17 (26.1) | 52 (53.6) | 17 (60.7) | 0.05b | 11.87 ± 4.82 | 0.103 |

| No: 104 (54.7) | 48 (73.9) | 45 (46.4) | 11 (39.3) | 10.72 ± 3.18 | |||

| Electricity/gas supply cut off | Yes: 59 (31) | 14 (21.5) | 41 (42.3) | 4 (14.3) | 0.006b | 11.94 ± 4.84 | 0.106 |

| No: 131 (69) | 51 (78.5) | 56 (57.7) | 24 (85.7) | 10.83 ± 3.42 | |||

| Have to leave the current house | Yes: 28 (14.7) | 5 (7.7) | 19 (19.5) | 4 (14.3) | 0.194 | 13.55 ± 5.90 | 0.042b |

| No: 162 (85.3) | 60 (92.3) | 78 (80.5) | 24 (85.7) | 10.77 ± 3.37 | |||

| Have to leave food due to expenses | Yes: 55 (29) | 13 (20) | 36 (37.2) | 6 (21.5) | 0.07 | 11.82 ± 4.96 | 0.192 |

| No: 135 (71) | 52 (80) | 61 (62.8) | 22 (78.5) | 10.90 ± 3.42 | |||

| Unpaid medical dues | Yes 96 (50.5) | 46 (70.7) | 37 (38.2) | 13 (46.5) | 0.288 | 11.72 ± 4.26 | 0.199 |

| No: 94 (49.5) | 19 (29.3) | 60 (61.8) | 15 (53.5) | 10.89 ± 3.66 | |||

| Skip medicines/treatment | Yes: 96 (50.5) | 22 (33.8) | 54 (55.7) | 20 (71.5) | 0.012b | 11.63 ± 4.07 | 0.129 |

| No: 94 (49.5) | 43 (44.2) | 43 (44.3) | 8 (28.5) | 10.69 ± 3.69 | |||

| Buy medicines in less than the required quantity | Yes: 107 (56.3) | 29 (44.6) | 61 (62.9) | 17 (60.7) | 0.099 | 12.01 ± 4.29 | 0.002b |

| No: 83 (43.7) | 36 (55.4) | 36 (37.1) | 11 (39.3) | 10.11 ± 3.07 | |||

| Missed surgeries due to expenses | Yes: 64 (33.7) | 19 (29.2) | 29 (29.9) | 16 (57.2) | 0.004b | 12.81 ± 5.09 | 0.008b |

| No: 108 (56.8) | 32 (49.3) | 64 (66) | 12 (42.8) | 10.66 ± 3.03 | |||

| NA: 18 (9.5) | 14 (21.5) | 4 (4.1) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Missed doctor’s appointment due to expenses | Yes: 110 (57.9) | 42 (64.6) | 51 (52.6) | 17 (60.7) | 0.052 | 12.29 ± 4.56 | 0.001b |

| No: 80 (42.1) | 23 (35.4) | 46 (47.4) | 11 (39.3) | 10.19 ± 2.91 |

Impact of Liver Disease and Its Severity on Socioeconomical Status and Treatment Compliance

Due to the worsening economic status, treatment compliance in CLD patients was also considerably affected. Nearly half of the patients had to leave or cut short their medicines or skip physician’s appointments due to expenditures and one-third were not able to afford a surgical procedure (Table 2). Less than 10% of patients were covered by any sort of medical insurance to cover their expenses.

The severity of disease affected the socioeconomic status significantly (89% in CTP C vs. 40% in CTP A). That also influenced the treatment compliance of the patients in terms of need to cut short medications (71.5% in CTP C disease vs. 33.8% in CTP A, P value: 0.012), delayed children education (60% in CTP C vs. 26% in CTP A), delay in loan payment (50% in CTP B vs. 28% in CTP A) and stopped saving (89% in CTP C vs. 50% in CTP A) (Table 2). Similarly, patients with worsening socioeconomic status had significantly higher MELD scores as compared to those with stable socioeconomic status (Table 2), which again signifies the impact of severity of disease on the financial burden faced by this group of patients.

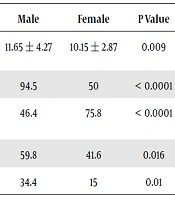

In our analysis, we also found that although male patients were suffering from more severe disease, they gave more importance to work. This led to cutting short their medications and missing surgical procedures significantly more than the opposite gender (Table 3).

| Male | Female | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The severity of disease using MELD score | 11.65 ± 4.27 | 10.15 ± 2.87 | 0.009 |

| Importance to work | 94.5 | 50 | < 0.0001 |

| Dependency on others to bear expenses | 46.4 | 75.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Need to cut short medicines | 59.8 | 41.6 | 0.016 |

| Miss surgical procedures | 34.4 | 15 | 0.01 |

Impact of Gender on Disease Status and Treatment Compliancea

5. Discussion

Worldwide, around 2 million deaths occur every year due to liver diseases, half of them are attributed to complications of CLD (19). It not only causes high mortality but also highly impacts economics (5). Quality of life indices are found to be low in patients with CLD (10). According to WHO data, South-East Asia carries the highest morbidity of CLD, with 808 DALY per 100,000 population and 801 YLL per 100,000 population (6).

Chronic liver disease is the 8th leading cause of the healthy-life-year loss in Pakistan (20). Furthermore, it is one of the leading causes of hospital admissions and mortality in Pakistan (21-24). Due to a very high load of CLD, Pakistan was labeled as a cirrhotic state (25). Hepatitis C (40% - 90%), followed by Hepatitis B (10% - 46%), is by far the foremost cause of chronic liver disease in Pakistan (26-28). Pakistan carries a 7 million hepatitis C infected population, the second-highest after China (29).

Chronic liver disease puts a pronounced burden on the healthiness of the state (30). Even though the HRQoL in patients has been considered and has turned into a matter of deep concern recently (4), the economic encumbrance of the illness on the whole family unit is yet an ambiguous area that entails additional exploration. This is fundamental as by means of this we would be able to guesstimate if the family can engross the cost of the treatment and whether or not there will be persistent compliance with therapeutics in the event of a liver transplant. Similar findings were observed in a study based on MEPS data reporting lower employment rate (44.7% vs. 69.6%), higher disability-related loss of work (30.5% vs. 6.6%) and workdays (10.3 vs. 3.4), and substantial health care expenses each year (USD 19,390 vs. USD 5567) in patients with CLD vs. non-CLD (10). The study also reported worse self-reported health status, more daily activity limitations, and lower quality of life in CLD patients. Moreover, presence of CLD itself significantly predicted unemployment (odds ratio, 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.50 - 0.70), yearly health care expenses (β = USD 9503 ± USD 2028), and effect on every facet of HRQoL (all P < 0.0001). Although they had a comparison arm of non-CLD patients, however, their study was limited due to the retrospective nature and bias of coding in the database. Moreover, they did not compare the effect on the severity of liver disease on outcomes.

Taking into account the part of the world where this particular study was carried out, the majority of the patients with CLD belonged to the low socioeconomic status. We have shown that CLD poses a substantial monetary and socioeconomic burden on patients and their family, so much so that this population is incapable of functioning economically with these pressures and consequently acquire debts which sustain an additional economic burden. This vicious cycle thereby turns this chronic sickness into one which necessitates not merely medical management but also ample financial management. We have shown that numerous sacrifices are required to be made by the family in order to endure medical therapy. This is vital as economic problems backing up to medical compliance are not regularly explored (31).

The stage of the disease is an important factor influencing the cost of treatment. We demonstrated not only the effect of liver disease on daily living expenses and medical compliance but also the impact of severity of liver disease on their worsening economic status. Our findings were in accordance with Bajaj et al., who also showed that the severity of the liver disease is directly related to the financial and socioeconomic burden faced by the patients and their families. This impacted daily life activities significantly, including their capability to meet the expense of food and lodging. This, in turn, shakes the medication compliance and adherence to the treatment (32). However, in their study, all patients had effective health insurance. Hence the actual monetary load was not captured. While in our study, only 10% of patients were covered by health insurance which helped us determine the exact impact of a financial burden on daily life and medication adherence. Also, their potential geographical selection bias limited the generalizability to our country with the different health systems. In two similar studies from Iran, the total annual cost per patient based on purchasing power parity (PPP) increased with the severity of liver disease. It was 3094.5 USD, 17483 USD, & 32958 USD in the year 2012 for chronic hepatitis B, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), respectively (33). While it was 1625.5 USD, 6117.2 USD, and 11047.2 USD in the year 2015 for chronic hepatitis C, cirrhosis, and HCC, respectively (34). The cost of disease treatment has significantly impacted their household economy, and patients either had to sell their assets or get loans (34). However, they did not categorize the severity of cirrhosis on the basis of CTP or MELD score in both these studies. Miyazaki et al. demonstrated the high level of burden, stress, and depression in caregivers of liver disease patients, however, they did not look into the financial component (35).

We also tried to highlight the effect of gender on perception of liver disease and response in terms of health-seeking behavior, compliance with medication, and management of limited available finances. The Iranian study in chronic hepatitis B patients also confirmed that the gender, age, the severity of illness, and the length of stay has a profound impact on financial burden on households (P < 0.05) (33).

Our report from a developing country highlighted the hidden problems faced by CLD patients as a family unit. Through this study, we are now well cognizant of the previously ignored economic facet of the problem of CLD, and as the public, in general, would be made attentive of this, improved support programs can be instigated and ample counseling of the patients and their caregivers can be done.

The cross-sectional design appears to be one of the limitations of our study. A prospective long-term study can gather evidence about indices of burden and stress at various stages of the disease in a single patient and can better inspect the relationship between burden and disease variables.

5.1. Conclusions

Chronic liver disease imposes incredible socioeconomic encumbrance on patients and the family unit. Chronic liver disease associated expenditures influence the family unit’s everyday working and therapeutic compliance, which is directly linked to the severity of disease expressed in terms of CTP and MELD scores. There is an exigent requirement of development in social health structure with emphasis on improved preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic facilities at an affordable cost.