1. Background

Childhood obesity (CO) is currently one of the leading public health concerns internationally (1, 2). An Iranian national study revealed that about 30% of children and adolescents aged 7 - 18 years had excess weight and abdominal obesity (3). Therefore, prevention and management of CO remains a public health priority and necessitates success for obesity control (4, 5).

In recent years, community-based strategies in obesity prevention programs for children have been emphasized (6). For many reasons, community-based prevention programs often receive little or no support in many communities (7). Evidence has shown that an intervention may fail, if a community is not ready to recognize the issue as a concern or problem (8). Community readiness (CR) is defined as the extent to which a community can be prepared to take action against or make changes on an issue (9). Readiness assessment informs planners about the feasibility of conducting a prevention program and helps to explore tailored capacity-building strategies according to the readiness stage of a community (10, 11).

Several tools and conceptions of readiness exist to determine the readiness stage for a specific issue or problem (9, 12-14). One widely used and flexible tool was developed at the Colorado State University based on the community readiness model (CRM) (9).

The CRM defines six dimensions, including: (1) existing prevention efforts (e.g., programs, activities, policies); (2) community knowledge of the existing prevention efforts; (3) leadership (e.g., the extent to which appointed leaders and influential community members are supportive of prevention efforts); (4) community climate (e.g., prevailing attitudes within the community concerning the issue); (5) community knowledge of the issue (e.g., signs, statistics, and consequences), and (6) available resources to support a prevention effort (e.g., funding, environmental, staff, and volunteers). These dimensions are scored for readiness in the CR tool by conducting in-depth interviews with the community’s key informants. Interviews are then transcribed, and each dimension is scored on a nine-point descriptive statement anchored rating scale (Appendix 1) (9). Using the CRM with the potential to achieve a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis provides a framework for adjusting the intervention towards existing strengths and opportunities of an organization or community (9, 15, 16).

According to the worrying upward trend of CO in Iran (3), interventions aimed at improving life style and weight status by focusing on prevention efforts are essential. Despite this particular need, only a national primary health care-based program has been initiated for preventing CO in Iran (17), while no understanding of CR in the Iranian socio-cultural context is in place. Thus, the Community Readiness Improvement for Tackling Childhood Obesity (CRITCO), using the CRM, planned to improve the readiness stage of targeted local communities for engaging CO prevention programs. Accordingly, the present paper aimed to describe the fourth phase of CRITCO study, comprising the rationale and process of developing an intervention package, including the formulation of strategies, community engagement process, action plan, and evaluation process.

2. Objectives

The primary objective of CRITCO is improving the readiness of targeted local communities of diverse socioeconomic districts of Tehran, Iran, for engaging CO prevention programs in late primary school children (10 - 12 years of age). In this regard, the specific objectives have been developed around the six dimensions of CRM, including the community knowledge from the existing preventive efforts and CO issue, promote the leaders’ support, community partnership, and resources allocation to address CO.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

The CRITCO development process included five distinct phases, where each phase was developed based on the previous phase’s findings. The first three phases conducted from August 2018 to April 2019 are as follows: In the first phase, after three rounds of Delphi study, the necessity/appropriateness and adequacy of all dimensions of CRM for preventing CO in the context of Iran were confirmed by 26 Iranian experts (Appendix 2). In the second phase, after assessing the linguistic, content, and face validity of a verified CR tool (18), a Persian version of CRT was adopted. In the third phase, a cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the readiness of 12 local communities from two diverse socioeconomic districts of Tehran to engage with CO prevention programs. Then, 66 key informants (KIs) were interviewed, and environmental scans were conducted (Appendix 3). In this study, each “local community” included an elementary school with students’ families, a related public health care center, and a municipal community center in that neighborhood. The results revealed that the overall readiness stage of all the local communities studied corresponded to the fourth stage of readiness: the “preplanning stage” (9). There was no difference in overall readiness stage between local communities with high and low socioeconomic status (SES) and between girls’ and boys’ schools (See Appendix 4). Details of the Delphi study, interview guide adoption, validation, and readiness assessment are explained elsewhere (19).

3.2. Phase 4: Developing CRITCO Intervention Package

3.2.1. Study Setting and Design

During June 2019, CRITCO study moved into phase 4 to develop an intervention package of a 6-month controlled quasi-experimental community-based program based on the obtained readiness level data. In this study, eight of the 12 local communities involved in phase 3 (4 interventions; 4 comparisons) were selected because of funding restrictions.

The intervention sites were chosen according to the site-specific readiness stage and their willingness to engage in the intervention. Therefore, two motivated local communities in each district corresponding to the preplanning stage of readiness were identified as the main settings for intervention. Also, the comparison groups included four local communities selected from the rest of the communities considering their readiness level, as well as location to minimize contamination from the intervention communities and to maximize comparability with the intervention groups. Local communities’ readiness scores and their late primary school student population in the intervention and comparison groups are presented in Appendix 5.

Target audience: Based on the local community definition, the school personnel, late primary school students, families, principals, and/or nutritionists of the public health care centers and municipal community centers were the audiences of the intervention.

3.2.2. Strategic Planning Approach

In each local community, establishing the relationship and building partnership among the target audiences was emphasized as the core approach of the intervention program. This partnership was intended to create the necessary infrastructure for collaboration and facilitate planning and implement tactics to support determined strategies.

3.2.3. Conducting a SWOT Analysis

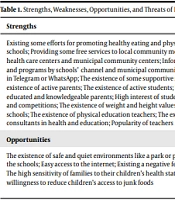

The strategies should be congruent with the stage of readiness and socio-culturally appropriate (9, 20). Hence, SWOT analysis was used as a tool to combine local data and community ideas to develop target healthy weight promotion strategies for the intervention sites through the following two steps: (1) The first step was identifying the core themes (16). In this regard, 33 main themes, including 12 strengths, 10 weaknesses, five opportunities, and six threats, were emerged from data obtained through the environmental scan, interviews, and readiness level assessment (19). As some themes overlapped between physical activity and healthy eating, they were presented in Table 1; (2) The second step involved transforming the themes that emerged in the first step into strategies (21). In this regard, the project advisory committee (PAC), in partnership with KIs (using focus group discussions [FGDs]), developed SWOT analysis strategies. The PAC comprised of five experts from four different expertise including two community nutritionists, a sociologist, a health education and promotion specialist, and a pediatrician.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Existing some efforts for promoting healthy eating and physical activity in schools; Providing some free services to local community members by public health care centers and municipal community centers; Informing about news and programs by schools’ channel and municipal community centers’ channel in Telegram or WhatsApp; The existence of some supportive school principals; The existence of active parents; The existence of active students; The existence of educated and knowledgeable parents; High interest of students in sports classes and competitions; The existence of weight and height values of students at schools; The existence of physical education teachers; The existence of school consultants in health and education; Popularity of teachers for students | The irregular and temporary efforts; Lack of parents attending the school group meetings; Lack of school principals involvements; Lack of information exchange among families and schools; Skipping breakfast by most students; Bringing some unhealthy food items to school; Selling some unhealthy foods by school buffets; Lack of schools funding and facilities for physical activity; Lack of a separate school health channel in Telegram or WhatsApp; Limited school time |

| Opportunities | Threats |

| The existence of safe and quiet environments like a park or playground around the schools; Easy access to the internet; Existing a negative feeling towards CO; The high sensitivity of families to their children’s health status; Families’ willingness to reduce children’s access to junk foods | The low familiarity of families with the services and programs of public health care centers and municipal community centers; Community resistance to education; The existence of some misconception towards CO; Restricted parental time; The weather conditions like cold and polluted weather; The existence of unsuitable environments like grocery stores around the schools |

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats of Intervention Sites to Engage with Childhood Obesity Prevention Programs

Focus group discussions: Four FGDs were conducted with KIs of intervention sites who had participated in CR interviews in the third phase of the study (Appendix 6). The discussion sessions were conducted around study goals, expected outcomes, and the importance of CR and building partnerships. Each FGD session was held at the targeted schools and facilitated and documented by two trained members of the research team. The number of participants in each FGD ranged from 5 to 6 (total = 22).

At the beginning of each discussion session, a trained nutritionist informed the attendees about the goal and planning approach of the project and core SWOT themes. Then, the participants were asked to suggest suitable strategies considering the core SWOT themes, environmental barriers, available resources, socio-cultural characteristics of the community, knowledge, and community perceptions related to healthy weight/diet and physical activity. Each FGD took about 145 to 166 minutes and was transcribed verbatim. All transcripts were imported to the MAXQDA 2010 and thematically analyzed by two independent analysts. Themes were classified and organized into five major themes including: (1) Education, including direct or indirect, individual- or group-based education; (2) Encouragement of students, families, and school personnel to physical activity and healthy food choices; (3) Informing about the CO issue and consequences, common misconceptions, and current efforts; (4) Creating supportive environments for physical activity and healthy eating; and (5) Sensitizing all local community members to the topic of CO, physical activity, and healthy diet.

Then, at two sessions, the final SWOT strategies were developed considering the strategic planning approach, core SWOT themes, and major themes derived from the FGDs, by the PAC (Table 2). As the specific impact of each recommended strategy can be attributed to several dimensions of CRM, alpha numerals in box brackets were used to show attributed dimensions to each strategy.

| S-O Strategies | W-O Strategies |

|---|---|

| Enhance the existing school efforts (S1 S4 O3 O4 O5) [D1 D4]; Enhance the schools’ and municipal community centers’ channel (S3 S7 O2) [D1 D5]; Organize more outdoors activities (S4 S5 O1) [D1 D4 D6]; Encouragement of students to physical activity at school (S8 S10 O3 O4) [D1 D4 D6]; Develop the collaboration between school and public health care center for exchanging the information (S2 S4 S9 S10 O3O4) [D1D5 D6]; Improve the teachers’ engagement in preventive efforts (S12 O3 O5) [D1 D3 D5 D6] | In conjunction with S-O1, capitalize on the enthusiasm of key individuals to evaluate regular execution of the initiatives (W1 O3 O4) [D1 D3]; Sensitize the families to childhood obesity issue (W2 W4 W6 O2 O3 O4) [D1 D5]; Sensitize the principles to children’s obesity (W3 O3 O5) [D3 D5]; According to S4 and S11, develop a school health channel in Telegram or WhatsApp (W4 W9 O2 O4) [D2 D5 D6]; Enhance the school snack/school breakfast program (W5 O3 O5) [D1]; Create a supportive environment at schools (W7 O3 O4 O5) [D1 D6] |

| S-T strategies | W-T strategies |

| Informing about available free services (S3 T1) [D2 D6]; In conjunction with W-O2, initiate a program around the common misconception, prevalence, and consequences (S2 S4 S9 S11T3) [D1 D4]; Enhance the families’ engagement (S2 S4 S5 T4 T5) [D1 D4] | Appoint a task force to assess local community outdoor facilities (W8 T5)[ D6]; Have a survey to prioritize programs to direct the school and parental time (W10 T4) [D4] |

3.2.4. Development of an Action Plan

The PAC developed an action plan to guide the activities expected to perform in partnership with the local community members. The action plan was developed based on the SWOT strategies as a living document that could be compatible with the needs, resource allocation, SES, and interests of each local community (Table 3).

| Specific Objectives a | Activities |

|---|---|

| Promoting CO prevention efforts | Develop a weekly School Breakfast Program/healthy school snack; Develop monthly sports competitions in the school setting; Provide educational programs for parents on school channels and/or school group meetings in partnership with municipal community centers and public health care centers; Conduct Healthy Food Festivals in collaboration with municipal community centers and parents every two months; Provide pamphlets and educational content in partnership with active students; Improve the teachers’ engagement by delivering training programs and healthy eating competitions; Enhance the schools’ channel by offering educational content and animations to families; Appoint a task force to record the programs implementation process; Appoint a task force for daily evaluation of the school buffets; Organize outdoor sports competitions for parents |

| Promoting community knowledge of prevention efforts | Create a separate school health channel; Introduce the available free services in the school health channel; Review existing efforts in the group meeting for parents |

| Promoting leadership support from prevention efforts | Conduct in-person meetings with school leaders, active parents, and students and invite them to collaborate; Provide educational programs and statistics to school principals and teachers; Conduct in-person meetings with school principals to Promote their engagement to evaluate current efforts |

| Promoting community climate/partnership to address CO | Implement local focus groups to modify misconceptions about CO; Initiate outdoor group educational or competition activities for parents; Merge several programs to direct the school and parental time; Improve the engagement of parents and teachers by holding group meetings |

| Promoting community knowledge about CO | Initiate a shared program between the school and public health care center for exchanging the information; Develop educational programs through in-person presentation and school health channel; Post pamphlets and posters for parents |

| Promoting resources | Assess around the school for organizing school physical activity classes and competitions; Train the students by active students and parents |

Recommended Intervention Action Plan around the Specific Objectives

3.2.5. Gaining Community Support to the Project

A community engagement and support process will be conducted in each site in a similar manner. The General Office of Education officially will write to the Office of Education in the two selected districts, and they will write to all principals of target and comparison schools. Then the research team meets with each school principal, public health care centers’ nutritionist, and municipal community center’s leader to seek their support as partners.

3.2.6. Food and Nutrition Committee (FNC) Establishment

As building relationships among target audiences was emphasized as the core approach of intervention program, for making a collaborative effort involving the local stakeholders, six to eight representatives from each school, parents, municipal community center, and public health care center will be chosen purposively based on their community engagement and interest in health issues to establish an FNC in each intervention site. It is expected that the FNCs focus on all aspects of project activities, and their meeting will occur at least once a month in the school.

3.2.7. Monitoring and Evaluation

A data collection form regarding all activities processes, quality, scale, duration, frequency, community partnership, and associated resources will be developed to be filled by FNCs’ members. The process evaluation data will be compiled and completed into one data file and presented to the PAC and FNC members at the monthly meeting by a research team member. At the end of the intervention, the difference in readiness scores among each intervention and comparison group at baseline and follow-up will be used to evaluate the efficacy of the CRITCO study. In this regard, interviews using the same CR interview guide and environmental scans will be conducted in all intervention and comparison sites. All persons interviewed at baseline will be approached for follow-up interviews at the end (Appendix 7).

4. Discussion

This paper provides an overview of the fourth phase of CRITCO study by focusing on the rationale and process of developing the intervention package for improving the readiness stage of two diverse socioeconomic districts of Tehran to engage with CO prevention programs.

A low level of CR to mobilize can impact program success due to inadequacies in the community partnership, leadership support, and available resources. Therefore, applying dimension-specific strategies is the key to success and ensuring any prevention program (7, 9). Although some cross-sectional studies indicated the feasibility of CRM to assess community readiness in the field of CO (16-24), available evidence regarding applying the readiness level data to explore tailored interventions for addressing CO is limited. In this regard, SaludABLEOmaha’s study in 2011 - 2013 used CRM as an initiative approach to increase the readiness of American residents in the Midwestern Latino community to address adolescent obesity (21). Also, two more studies in the US and Australia entitled “childhood obesity prevention program” (COPP) and “It is Your Move” (IYM) used the readiness level data to access changes in community readiness (22, 24).

Applying CRM in an Iranian community for the first time is one of the strengths of the current study. Also, using SWOT analysis as a framework for matching the intervention strategies in combination with local data and community ideas is another strength. Besides, the action plan is designed as a living document to ensure the participation of key community stakeholders in its development and seeking their ongoing feedback.

However, the study has certain limitations. Although a randomized controlled trial design would have been technically ideal, a quasi-experimental design will be used because of funding restrictions. Also, a selection bias could be risen by purposive sampling of KIs; thus, an attempt will be made to minimize the bias by inviting a wide range of informants.

4.1. Conclusion

The current detailed report described the fourth phase of CRITCO study, including strategy development and action plan, which are essential pre-requisites for planning any preventive programs for childhood obesity relying on efficient community readiness to engage. This study provides valuable information to guide the public health policymakers in planning and executing public health interventions.