1. Background

Mental disorders are among the most common health problems worldwide (1). In many societies, women are more prone to mental disorders than men due to various individual and social factors (2-4). The findings of a national survey in 2015 revealed that about one out of four Iranian adults were suspected of suffering mental disorders, ranging between 21 to 34.2% in different regions, with a higher prevalence in women and urban districts than in men and rural areas (5). Accordingly, a recent systematic review showed that the point prevalence of major depressive disorders in Iran was 4.1%, showing a 1.95-time higher rate in women than in men (6). Anxiety prevalence has been reported as 36 and 27% in Iranian women and men, respectively (7). Another study in Iran indicated a higher frequency and intensity of stress in women than in men (8). The considerable prevalence of emotional distress in women makes them vulnerable to several chronic diseases (9). Beyond the mentioned personal effects, emotional distress in women could negatively affect their maternal roles in shaping children’s healthy lifestyles, leading to childhood obesity and poor health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (10).

Childhood obesity shows a rising trend in Iran, similar to many developed and developing countries during the last decades (11-13). Being overweight is a multifactorial phenomenon, and several personal and environmental factors can predispose children to this condition (13). The child’s weight has a deep correlation with the family environment and parental characteristics (14, 15), particularly the mother’s eating style and emotional state (16-20). Our recent research highlighted the vital roles of maternal socio-demographic and cardio-metabolic characteristics in distinguishing parental risk clusters, as one of the main predictors of obesity in children (21). These findings were confirmed by other studies in other communities (22, 23). Despite existing indigenous information on the relationship between maternal socio-demographic and metabolic characteristics, similar data on maternal emotional factors and their children’s weight status are limited to the information obtained from other societies, especially Western countries (24, 25). In this regard, previous findings showed that maternal depressive symptoms increased sedentary behaviors in children, which could directly affect their weight status (26, 27). Also, available data suggest that mothers’ psychological stress is associated with reduced consumption of fruits and vegetables, lower physical activity, more sedentary behaviors (14, 15, 27), and a higher risk of excessive weight gain (16, 17) in offspring. More evidence revealed that the children of anxious mothers were more likely to suffer from sleeping and eating problems, which could negatively affect their weight status (18, 19).

Existing evidence also showed that maternal emotional distress, including depression, anxiety, and stress, might negatively affect different aspects of offspring’s health, including mental health, social functioning, and learning abilities (18, 24, 28). In addition, the children whose mothers suffer from emotional distress are more likely to report poor HRQoL (29, 30). Health-related quality of life, as an essential health outcome, is defined as a comprehensive and multidimensional concept for assessing the patient’s perspective about the impact of health or disease on his/her physical, mental, and social well-being (31). The association between the child’s weight status and HRQoL has already been revealed, with several studies indicating the negative impact of childhood obesity on HRQoL (25, 32). Studies from Iran have also shown lower HRQol scores in obese children than in their over-or normal-weight counterparts (33, 34), which can be observed in a gender-specific pattern (35). Given the association of the maternal emotional state with offspring’s weight status and HRQoL and the relationship observed between children’s weight status and their HRQoL, it is reasonable to assume that the negative effect of maternal emotional distress will be intensified in overweight children. There is a lack of evidence regarding the potential link between the maternal emotional state and offspring’s weight status in Iran. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, no investigation has studied the mediating role of children’s weight in the link between the maternal emotional state and offspring’s HRQoL. Therefore, using a structural equation modeling approach, in the current study and for the first time, we aimed to simultaneously investigate the direct and indirect effects of maternal emotional states, including depression, anxiety, and stress, on children’s weight status and HRQoL among a population of Tehranian families. Examining the mentioned associations between the maternal emotional state and offspring’s HRQoL can provide more insights into the impact of the maternal-child relationship on children’s health. Such information would also be helpful for healthcare providers and policymakers.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Participants

The Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS) is a longitudinal survey designed to determine cardiovascular risk factors in the urban district 13 of Tehran, located in the middle of the city, and assess lifestyle modifications to decrease the prevalence of non-communicable diseases. The participants’ age distribution represented Tehran’s total population. The related measurements for all participants were conducted at the baseline (1999-2001) and repeated every three years. Further details regarding the rationale and design of the TLGS have been reported elsewhere (36, 37).

The data related to all school-aged children (aged 8 to 18 years) who participated in TLGS during 2014 - 2016 were considered for the current study (n = 309). After excluding those with incomplete maternal information (n = 78), 231 children (51% boys) and their mothers were recruited for the final analysis. The participants provided informed written consent. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences (RIES) (IR.SBMU.ENDOCRINE.REC.1397.130).

2.2. Measurements

Data on the age and anthropometric indices, including the weight and height, of children were collected by trained interviewers and staff. The participant’s weight was measured using a digital scale while wearing minimum clothing and no shoes, and the height was measured in a standing position without shoes and shoulders in a normal alignment. To determine BMI-for-age (BMI Z-score), WHO AnthroPlus (version 3.2.2) and macros software were used.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in children was measured using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ version 4.0 (PedsQL™ 4.0) Generic Core Scales which consists of items and four subscales (physical, emotional, social, and school functioning) (38). For each item, children choose their answers from a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4 (0 = never a problem and 4 = almost always a problem). To score the scale, each item is reversely scored, with higher scores indicating a better HRQoL. Previous studies have assessed and reported the reliability and validity of the Persian version of PedsQL™ 4.0 in Iranian children (8 - 12 years old) and adolescents (12 - 18 years old) (39, 40).

In the current study, maternal data, including age, education, working status, and emotional state, were gathered. Maternal emotional states were assessed using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale- 21 Items (DASS-21). As a short and user-friendly self-report questionnaire, DASS-21 is applied to measure three related states of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms (41) in both clinical and community settings (42, 43). Each scale of DASS-21 contains seven items, and each item is scored on a four-point Likert scale from 0 to 3 (0 = it is not applied to me at all, and 3 = it is applied to me very well, or most of the time). The score of each scale is calculated by summing the scores of relevant items, and a higher score in each of the scales of depression, anxiety, and stress indicates a more severe condition. This tool can differentiate stress from depression and anxiety (44), making it a suitable tool to assess these emotional states in a population-based study, such as the TLGS. The sensitivity and specificity of the questionnaire were 75 and 89%, respectively (45, 46). The validity and reliability of the Persian version of DASS-21 used in the current study have been confirmed and reported previously (47). Moreover, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales were 0.77, 0.79, and 0.78, respectively. In addition, the correlation coefficients of this inventory with Beck’s Inventory, Zung Anxiety Test, and Perceived Stress Inventory were reported as 0.7, 0.67, and 0.49, respectively (48).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

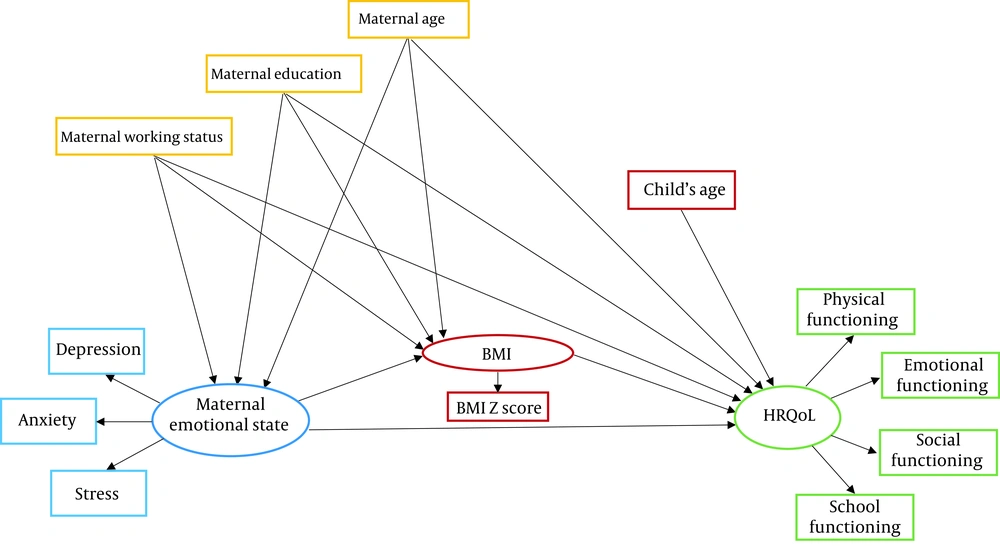

Data were represented as mean ± SD for normally distributed variables and as median (quartile 1, quartile 3) for variables with non-normal distribution. Normality assumption was examined by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The chi-square test was conducted to compare categorical variables between boys and girls. Independent samples t-test or its alternative non-parametric method, the Mann-Whitney U test, was used for comparing means between the two groups. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used for examining direct and indirect associations among the measured variables. The hypothesized conceptual model, used to examine interrelationships between the variables, has been illustrated in Figure 1. Maternal education, age, and employment status, which described the maternal socio-demographic status, were regarded as exogenous independent variables. The maternal emotional state and the child’s BMI were entered in the model as mediators, and the child’s HRQoL was considered as the final dependent variable. The maternal emotional state and children’s BMIs were considered as latent constructs and measured by their special indicators. Multiple group SEM analysis was conducted for sex-specific evaluations. The maximum likelihood method and Bayesian analysis were used for parameter estimation. Uniform distribution was set as a prior distribution of the parameters, and stability and admissibility were examined on prior data. Finally, the mean (95% confidence interval) of a marginal posterior distribution was reported as the parameter’s estimate (49). Fit indices, including the ratio of the chi-square value to DF (χ2/df), goodness of fit (GFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were calculated to measure the model’s adequacy and appropriateness of SEM analysis. Hooper et al. have reported the acceptable thresholds of fit indices (50). For data description and SEM analysis, IBM SPSS statistics 23 and AMOS 23 software were utilized, respectively.

3. Results

The mean age, BMI Z-score, and HRQoL total score of the participants were 13.8 ± 3.1 years, 0.74 ± 1.5, and 84.7 ± 11.3, respectively. Further descriptive statistics of the study participants by sex groups have been presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between boys and girls in the mean age, BMI Z-score, and the HRQoL scores of the social functioning and school functioning subscales; however, HRQoL scores were significantly higher in boys compared to girls in the physical and emotional functioning subscales. The mean age of the mothers was 42.2 ± 5.8 years; the majority of whom were housewives (80.5%) and had secondary levels of education (57.1%). There were no significant differences between the mothers of boys and girls comparing the DASS-21 score and the distribution of maternal employment status and education level.

| Variables | Total (n = 231) | Boys (n = 118) | Girls (n = 113) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children’s characteristics | ||||

| Age (y) | 13.8 ± 3.1 | 13.9 ± 3.0 | 13.8 ± 3.2 | 0.85 |

| BMI Z-score | 0.74 ± 1.5 | 0.63 ± 1.5 | 0.86 ± 1.4 | 0.23 |

| HRQoL (PedsQoL) | ||||

| Physical functioning | 89.6 ± 11.3 | 91.5 ± 9.9 | 87.6 ± 12.3 | 0.008 |

| Emotional functioning | 73.5 ± 18.7 | 77.1 ± 15.7 | 69.7 ± 20.8 | 0.003 |

| Social functioning | 89.1 ± 13.0 | 90.2 ± 11.3 | 88.0 ± 14.5 | 0.19 |

| School functioning | 83.7 ± 14.5 | 83.2 ± 13.8 | 84.2 ± 15.3 | 0.59 |

| Total HRQoL | 84.7 ± 11.3 | 86.3 ± 9.9 | 83.0 ± 12.4 | 0.03 |

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| Maternal age (y) | 42.2 ± 5.8 | 42.4 ± 6.2 | 41.9 ± 5.3 | 0.54 |

| Maternal level of education, No. (%) | ||||

| Primary | 36 (15.6) | 21 (17.8) | 15 (13.3) | 0.38 |

| Secondary | 132 (57.1) | 69 (58.5) | 63 (55.8) | |

| Higher | 63 (27.3) | 28 (23.7) | 35 (31.0) | |

| Maternal job status, No. (%) | ||||

| Housewife | 186 (80.5) | 94 (79.7) | 92 (81.4) | 0.86 |

| Employed/student | 45 (19.5) | 24 (20.3) | 21 (18.6) | |

| Maternal emotional state (DASS-21) | ||||

| Depression | 4 (0 - 10) | 4 (0 - 10) | 4 (0 - 10) | 0.89 |

| Anxiety | 6 (2 - 12) | 6 (2 - 14) | 6 (2 - 12) | 0.97 |

| Stress | 14 (8 - 20) | 16 (8 - 20) | 14 (6 - 22) | 0.38 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; DASS-21, depression, anxiety, and stress scale-21.

Based on multiple group analysis, the measurement model, in which the maternal emotional state was considered the same in the mothers of boys and girls, fitted significantly better on the data (Δχ2 = 27.65, DF = 14, P = 0.01) compared to the unconstrained model (in which all the parameters were considered different in boys and girls). Therefore, a sex-specific analysis was conducted considering a number of the mentioned constraints.

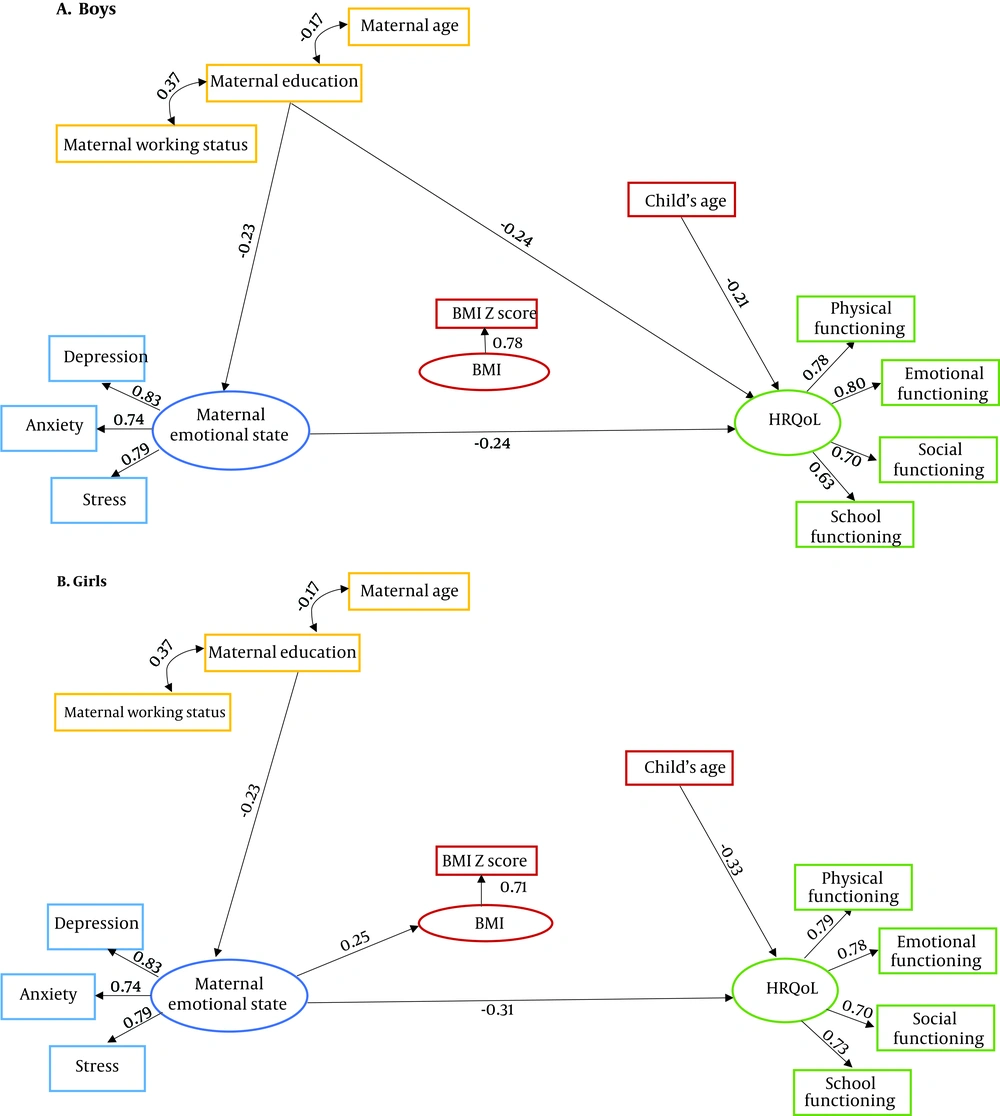

Figure 2 displays the final structural models in boys and girls, showing significant associations between the variables, and related standardized estimations have been noted above each path. The fit indices of SEM models (as noted below Figure 2), indicate acceptable thresholds for both boys and girls.

Final structural models after testing the relationships of maternal characteristics and emotional states with children’s body mass index (BMI) Z- scores and health-related quality of life (A, boys; and B, girls). Fit indices were acceptable for both structural equations modeling (SEM) in boys (χ2 = 69.8, DF = 42, χ2/DF = 1.66, RMSEA = 0.75, GFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.93, IFI = 0.93, NFI = 0.90) and girls (χ2 = 74.3, DF = 42, χ2/DF = 1.77, RSMEA = 0.80, GFI = 0.90, CFI = 0.91, IFI = 0.92, NFI = 0.91).

Table 2 displays the results of the examined structural model in terms of the sex-specific associations of maternal characteristics with children’s HRQoL. In the hypothesized SEM model, maternal age, education, and working status, as well as the child’s age, were the exogenous variables observed. The latent construct of the maternal emotional state and children’s BMI Z-score were mediators, and children’s HRQoL was the endogenous latent construct. The negative effect of maternal education on the maternal emotional state was significant in both boys and girls (β = -0.23, P < 0.05). Considering maternal variables, only the maternal emotional state had a significant positive effect on girls’ BMI Z-score (β = 0.25, P < 0.05). In terms of the determinants of the child’s HRQoL, in boys, the child’s age (β = -0.21), maternal education (β = -0.24), and maternal emotional state (β = -0.24), and in girls, the child’s age (β = -0.33) and maternal emotional state (β = -0.31) had significant negative impacts on HRQoL (P < 0.05 for all). Regarding indirect effects, maternal variables had no significant effects on the child’s BMI Z-score and HRQoL (P > 0.05).

| Predictors | Response | Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate a | 95% CI | Estimate a | 95% CI | ||

| Maternal age (y) | Maternal emotional state | -0.12 | (-0.26, 0.02) | -0.12 | (-0.26, 0.02) |

| Maternal education | -0.23 | (-0.37, -0.07) | -0.23 | (-0.37, -0.07) | |

| Maternal working status | 0.01 | (-0.14, 0.15) | 0.01 | (-0.14, 0.15) | |

| Maternal age (y) | Child’s BMI Z score | -0.10 | (-0.31, 0.13) | -0.06 | (-0.33, 0.22) |

| Maternal education | 0.10 | (-0.16, 0.36) | 0.11 | (-0.17, 0.39) | |

| Maternal working status | -0.13 | (-0.37, 0.12) | -0.21 | (-0.46, 0.07) | |

| Maternal emotional state | 0.12 | (-0.13, 0.37) | 0.25 | (0.06, 0.53) | |

| Child’s age (y) | Child’s HRQoL | -0.21 | (-0.40, -0.01) | -0.33 | (-0.53, -0.10) |

| Child’s BMI Z-score | 0.02 | (-0.25, 0.28) | 0.21 | (-0.10, 0.51) | |

| Maternal age (y) | -0.12 | (-0.03, 0.06) | 0.19 | (-0.05, 0.41) | |

| Maternal education | -0.24 | (-0.44, -0.02) | -0.14 | (-0.35, 0.08) | |

| Maternal working status | 0.05 | (-0.15, 0.24) | 0.12 | (-0.10, 0.34) | |

| Maternal emotional state | -0.24 | (-0.44, -0.04) | -0.31 | (-0.54, -0.08) | |

a Standardized path coefficients and their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

4. Discussion

The current study examined a conceptual model for recognizing the direct and indirect relations of mothers’ emotional states on their childrens’ BMI and HRQoL. Our results indicated that while the maternal emotional state could directly affect HRQoL in both girls and boys, it was associated with weight only in girls. Interestingly, in neither of the genders, the weight status was associated with HRQoL, so its mediating role in the association between the maternal emotional state and offspring’s HRQoL was not confirmed. In addition, among the maternal characteristics considered as influential factors in the initial hypothesized model, the level of education directly affected the maternal emotional state in the mothers of both boys and girls, but its effects on HRQoL was only significant in boys.

The current findings regarding the inverse relationship between the maternal emotional state and the child’s HRQol are consistent with the data reported by previous studies (30, 51, 52). Maternal depression and stress are accompanied by inappropriate parenting practices and reduced warmth and sensitivity in mothers’ interactions with their children, delaying the achievement of developmental milestones and leading to poor self-regulation and executive performance by children, as well as poor overall functioning (52, 53). In addition, anxious mothers, via transmitting negative emotional and thinking patterns to their children and the lack of providing a motivational environment in the family, reduce their children’s self-efficacy and success in future experiences (54).

Our results showed that the maternal emotional state was associated with a higher BMI level in girls but not boys. Several studies have reported a relationship between maternal emotional problems and the child’s overweight (29, 32, 55); however, only one study has explicitly investigated this relationship in a sex-specific pattern, focusing on maternal depression (56). The findings of the recent study were consistent with ours, indicating a significant association between maternal depression and a higher BMI only in girls, mediated by the low levels of physical activity in girls (56). Another study demonstrated that mothers with emotional problems were more likely to have unhealthy weight-related behaviors (25), and regarding same-gender role modeling, the impacts of the maternal lifestyle are greater on daughters than on sons, justifying the observed higher BMIs in girls (57-59).

In the present study, no relationship was observed between the weight status and HRQoL in both sexes, contradicting our initial assumption regarding the role of BMI in modulating the association between the maternal emotional state and their children’s HRQoL. The data available on the relationship between the weight status and HRQoL in children is controversial. Several studies have reported a negative association between the child’s weight status and his/her HRQoL (60, 61). Tsiros et al., in a systematic review conducted on 22 studies, reported an inverse linear relationship between BMI and HRQoL in children, using both pediatric self-reports and parent proxy-reports (62). Further evidence indicates that Iranian children with higher BMIs are more likely to report poorer HRQoL (33). However, consistent with our results, two studies from Kuwait and Fiji found no strong association between the weight and HRQoL in children (63, 64); both of which reported that HRQoL scores in children with overweight/obesity did not significantly differ from the corresponding values in their normal-weight counterparts.

Our findings regarding the negative relationship between maternal education and HRQoL in boys, but not in girls, are difficult to compare with those of other studies because there is no gender-specific study investigating this relationship. Nevertheless, contrary to our results, several studies have documented the positive relationship between maternal education and children’s HRQoL in other countries (65, 66) and Iran (67). It seems that highly educated mothers who cannot work because of their child care duties have more parenting stress and experience less satisfaction with their maternal roles (68). Considering the emergence of sexuality in early adolescence and increasing complexities in opposite-sex relationships in the family, maternal stress seems to have stronger effects on sons’ functioning (69). However, regarding the inconsistency of our findings with those of previous studies, more research is needed to clarify the relationship between the education of mothers and HRQoL in children. On the other hand, in our study, maternal education had a positive association with HRQoL in both girls and boys, which was mediated via the maternal emotional state and consistent with the findings of previous studies (70-72). Mothers with lower levels of education are more likely to suffer from depression and use negative and harsh parental practices, which adversely affect children’s mental well-being and their ability to learn (70, 72). Also, given that education is one of the indicators of socioeconomic status, mothers who are less educated have limited access to social support and childcare services, leading them to experience excessive parenting stress, which can impede their ability to adequately meet their children’s needs (73). Also, in this study, the HRQoL of children declined with age, which was also consistent with the observations of other studies (74, 75). As the age increases, puberty-related physical and hormonal changes can reduce the psychological balance (76). Also, because of the formation of new values and norms in adolescence, while seeking their new identity, teenagers may encounter social insecurity, moral contradictions, and an ambiguous future, which can ultimately impair their subjective well-being (75).

This study is one of the first efforts to explore the direct and indirect effects of the maternal emotional state on the child’s weight status and HRQoL using a structural equation modeling approach. Our findings also add important information to the literature regarding gender differences in the above-mentioned parameters and interactions. However, certain limitations also need to be considered. First, the cross-sectional design of this study did not allow us to assess causal relationships between the studied variables. This study was conducted on an urban population in Tehran city, which might limit the generalizability of our findings to rural and suburban populations. Finally, by investigating other influential factors, such as parents’ relationship quality and children’s coping strategies, it is possible to provide a more accurate picture of the association between the maternal emotional state and the child’s weight status and HRQoL.

In conclusion, our results highlighted the impacts of the maternal emotional state on the subjective health status of children (both girls and boys) irrespective of their BMIs. Further research is required to either confirm or debate the gender-specific findings of this study.