1. Background

The prevalence of obesity is increasing and according to the latest statistics of the world health organization, 13% of adults worldwide are obese and 39% are overweight (1). Obesity increases the risk of metabolic diseases, cancer, and cataract (2, 3). Statistics have shown that obesity and its consequences have high costs for communities (4). There is a positive association between body mass index (BMI) and direct and indirect (due to premature deaths) health care costs. Indirect costs of obesity (54% to 59%) have been reported more than the direct costs (5). In the last century, due to the increasing prevalence of obesity and its hidden costs, control and treatment of obesity requires more attention.

Weight loss (WL) in obese patients, in addition to improving clinical conditions, will increase the recognition and quality of life (6, 7). In order to lose weight, various methods, such as diet, physical activity, drug therapy, and surgery have been suggested. Given the potential side effects of drug therapy and surgery, dietary interventions for WL have always been the first priority for the subjects (8). However, a variety of diets for WL have been suggested.

The difference in body composition (muscle loss and dehydration), metabolic effects, and the return of weight has been reported (9, 10). In a meta-analysis study, weight return had been reported in most participants (77%), who followed WL diets (11). In a classification of diets based on calorie restrictions and speed of WL, diets are divided to rapid WL, moderate WL, and slow WL.

Although many studies recommended gradual WL diets for obese patients, many people would like to lose their excess weight in the shortest time (12). A significant number of people believe that rapid WL has side effects and cannot have beneficial clinical effects similar to slow WL. However, a systematic review found that people, who follow severe calorie-restricted diets will not have an eating disorder and will be able to maintain their lost weight (13). Several studies have shown that rapid WL with high calorie-restriction could cause an improvement of clinical state in obese individuals (14, 15).

Harder et al. reported that rapid WL could significantly decrease weight, triglycerides, total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, fasting blood glucose (FBS), hemoglobin A1c, and fasting serum insulin (FINS) (16). Also, Wahlroos et al. reported that a significant decrease in waist circumference, body mass index (BMI), subcutaneous abdominal fat volume, and insulin resistance occurred after rapid WL (17).

However, it seems that the effects of metabolic and anthropometric from slow WL are different from rapid WL. In a pilot study, the difference between these 2 diets on anthropometric status was reported (18). Also, Yudai et al. showed that body weight and total intra-abdominal fat mass in the rapid and slow WLs decreased to the same extent, yet muscle atrophy was significantly higher with rapid than slow WL (19). The review of studies showed that metabolic differences of these 2 types of diets are still unclear.

2. Objectives

The aim of this clinical trial study was to evaluate the effects of glycemic and lipid parameters of the two protocols on WL in obese and overweight people.

3. Methods

This double-blind clinical trial study was conducted on 42 obese and overweight individuals (25 < BMI < 35). Participants were selected from those, who referred to a nutrition clinic (Ahvaz, Iran). Participants were screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were lack of physical activity, no smoking, no alcohol drinking, no usage of herbal supplements and vitamins, and lack of weight changes in the last 6 months. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, breastfeeding, use of drugs that effect metabolism, lipid and glycemic profile, eating disorder, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney problems, thyroid, digestive, respiratory diseases, and cancer. Participants consuming more than 300 mg of caffeine daily (described as caffeine users) were excluded from the study (20). The level of physical activity was assessed weekly by phone. The subjects, who had moderate or various physical activities, were excluded from the study.

At the beginning, individuals were selected from the nutrition clinic. The initial screening had been done after a brief explanation of the study, and preliminary evaluation was done by phone. Next, a meeting with complete description of the protocol and justification for the study was arranged for the volunteers. The final screening was carried out in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eligible individuals, after filling the consent form, were randomly divided to 2 groups, rapid WL and slow WL.

Prior to WL, an ambulatory run-in period was imposed for each subject to insure stabilization of body weight (± 2 kg during 4 weeks). During the body weight stabilization, a three-day food dietary record was used to determine an individual’s daily food and beverage consumption to estimate their total daily caloric intake (2 weekdays and 1 weekend day). The subjects were randomly divided (according to age, gender and BMI) into two groups (rapid WL and slow WL). Rapid WL and slow WL, based on the lost weight (at least 5 %), were defined over a period of 5 weeks and 15 weeks, respectively (18). The prescribed calorie-restricted diet contained 15% protein, 30% to 35% fat, and 50% to 55% carbohydrate, on average, in order to provide WL. In general, the meal plans included 3 main meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) and three snacks (mid-morning, mid-afternoon, and bedtime), and low saturation and trans fats, cholesterol, salt (sodium), and added sugars. All diets were designed according to Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 (21). Low-calorie diets produced an energy deficit of 500 to 750 and 1000 to 1500 kcal per day for slow and rapid WL, respectively. At the end of the study, anthropometric and biochemical assessments were conducted on the individuals (18 individuals in rapid WL and 18 individuals in slow WL), who reached the desired WL. All subjects provided their written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (Act No. IR.AJUMS.REC.1394.212).

Body weight and body composition were measured using the direct segmental multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance method (Inbody 230, Biospace, Korea) (22). The measurements presented were fasting state, shortly after waking in the morning, and at a dehydrated state. Standing height without shoes was measured using a stadiometer. Body Mass Index was calculated with the following formula: weight (kg) / height2 (m2). Waist circumference was obtained at the level of the noticeable waist narrowing, located approximately half way between the costal border and the iliac crest and the level of the greatest posterior protuberance. Hip circumference was also measured in the region of the greatest posterior protuberance and at approximately the symphysion pubis level, anteriorly. Blood pressure was measured using an automatic blood pressure monitor (BM65, Beurer, Germany) after subjects rested for more than 10 minutes. All anthropometric and blood pressure measurements were done in triplicates and the mean was calculated for each subject. Resting metabolic rate was measured at baseline and following the dietary intervention by indirect calorimetry (FitMate, Cosmed, Rome, Italy), using resting oxygen uptake (VO2).

Blood samples (5 mL) were collected at the beginning and at end of the study during the 12-hour fasting condition. The samples were centrifuged at a low level and serum was separated. Biochemical measurements were performed immediately after sampling. Fasting blood sugar (FBS), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), triglycerides (TG), and TC were measured by an auto-analyzer (Hitachi, USA). The Friedewald formula was used to calculate LDL levels. Fasting serum insulin concentration was measured by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Mercodia). The homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) was calculated with the formula: HOMA-IR = [FBS (mg/dL)*FINS (μU/mL)] / 405. (23). Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) was calculated on the basis of suggested formulas: 1 / [log (Insulin μU/mL) + log (Glucose mg/dL)]. (24). The HOMA-B (pancreatic beta cell function) was computed as follow: 20 × FINS (μIU/mL)/fasting glucose (mmol/mL)-3.5. Insulin sensitivity was derived using the formula: HOMA-S (insulin sensitivity) = 22.5/(insulin (mU/L) × glucose (mmol/L)). All biochemical assays were performed in duplicates and the mean was calculated for each subject.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data were checked for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Independent sample t test (for normally distributed variables) and Mann-Whitney U test (for non-normally distributed variables) were used to compare baseline values between the 2 groups. Moreover, in order to assay differences before and after the intervention within groups, paired sample t test (for normally distributed variables) and Wilcoxon test (for non-normally distributed variables) were used. Data were reported as mean ± standard error. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

4. Results

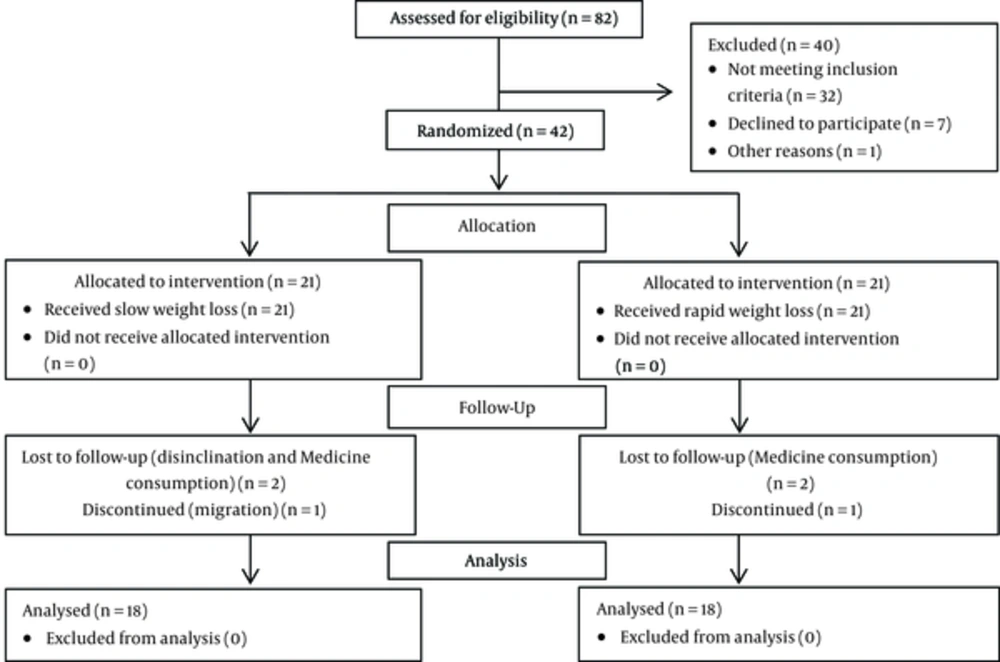

Of the forty-two participants assigned to the trial, thirty-six subjects completed the study (n = 18 in slow WL group and n = 18 in rapid WL group). During the study, 3 individuals in the rapid WL group (medication consumption and discontinued) and 3 in the slow WL group (disinclination, medication consumption, and migration) were excluded (Figure 1). No significant side effect in the two study groups was detected.

Baseline characteristics in rapid WL and slow WL groups are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were observed in baseline characteristics between the 2 groups (P > 0.05).

| Variables | Slow Weight Loss (n = 18) | Rapid Weight Loss (n = 18) | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.1 ± 11.2 | 34.4 ± 11.1 | NS |

| Female - N (%) | 13 (72.2%) | 13 (72.2%) | NS |

| Height (cm) | 161.4 ± 7.7 | 163.9 ± 9.7 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.2 ± 8.1 | 32.0 ± 6.3 | NS |

| PBF (%) | 42.5 ± 7.1 | 39.1 ± 10.2 | NS |

| SBP (mmHg) | 132.8 ± 18.9 | 133.0 ± 17.4 | NS |

| DBP (mmHg) | 83.7 ± 9.4 | 82.7 ± 8.7 | NS |

| Weight loss (%) | 6.2 ± 1.2 | 6.0 ± 0.8 | NS |

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic blood pressure; N (%), percentage of female participants; PBF, percentage of body fat; SBP, systolic blood pressure; Weight loss (%), the percentage of body weight loss (baseline weight - post intervention weight/baseline weight) × 100.

aAll values were means ± SD.

bBaseline slow weight loss group vs. baseline fast weight loss group (independent-sample t test for normally distributed variables and Mann-Whitney U for non-normally distributed variables).

As shown in Table 2, WL is statically the same in both groups (-5.47 ±1.46 and -5.12 ± 1.12 for slow and rapid WL, respectively, P > 0.05). The results of body composition, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate are given in Table 2. A significant reduction in anthropometric indices and RMR were detected in both groups. Significant differences in blood pressure and heart rate were seen in the 2 groups. Waist circumference and hip circumference in slow WL group had a significant reduction compared to the rapid WL group.

| Variables | Slow Weight Loss (n = 18) | Rapid Weight Loss (n = 18) | Δ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End | Baseline | End | Intragroupb | Intragroupc | Intergroupd | |

| Weight (kg) | 86.9 ± 16.1 | 81.4 ± 15.1 | 85.5 ± 15.3 | 80.3 ± 14.5 | -5.47 ± 1.46e | -5.12 ± 1.12e | 0.35 ± 0.43 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.2 ± 8.0 | 32.1 ± 7.6 | 32.0 ± 6.3 | 30.0 ± 6.0 | -2.10 ± 0.52e | -1.92 ± 0.43e | 0.17 ± 0.16 |

| WC (cm) | 98.9 ± 15.7 | 92.8 ± 15.0 | 98.3 ± 13.7 | 93.7 ± 13.2 | -6.09 ± 1.60e | -4.57 ± 1.72e | 1.52 ± 0.55f |

| HC (cm) | 101.6 ± 9.0 | 96.5 ± 8.4 | 104.4 ± 8.0 | 101.2 ± 7.4 | -5.07 ± 1.10e | -3.11 ± 2.15e | 1.95 ± 0.57f |

| WHR | 0.96 ± 0.1 | 0.95 ± 0.1 | 0.94 ± 0.1 | 0.92 ± 0.1 | -0.01 ± 0.01e | -0.01 ± 0.01e | -0.001 ± 0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 132.5 ± 18.6 | 128.0 ± 17.6 | 133 ± 17.4 | 130.1 ± 17.0 | -4.52 ± 12.12 | -2.88 ± 11.87 | 1.63 ± 4.00 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 83.7 ± 9.4 | 82.1 ± 8.9 | 82.7 ± 8.7 | 82.1 ± 8.1 | -1.61 ± 5.50 | -0.66 ± 6.61 | 0.94 ± 2.02 |

| Heart rate | 97.3 ± 15.7 | 97.1 ± 13.1 | 96.8 ± 15.0 | 94.2 ± 12.4 | -0.30 ± 9.54 | -2.58 ± 11.98 | -2.27 ± 3.61 |

| RMR (kcal) | 1583.1 ± 217 | 1560.1 ± 213.9 | 1638.6 ± 281.7 | 1579.3 ± 270.5 | -22.9 ± 26.5f | -59.3 ± 32.6e | -36.3 ± 9.9e |

| LBM (kg) | 27.5 ± 5.6 | 27.0 ± 5.6 | 28.9 ± 7.3 | 27.4 ± 7.0 | -0.52 ± 0.75f | -1.51 ± 0.80e | -0.98 ± 0.25e |

| FM (kg) | 37.3 ± 11.2 | 32.8 ± 10.9 | 33.6 ± 12.5 | 30.7 ± 11.9 | -4.52 ± 1.71f | -2.92 ± 1.34e | 1.59 ± 0.51f |

| PBF (%) | 42.5 ± 7.1 | 39.8 ± 7.9 | 39.1 ± 10.2 | 37.9 ± 10.5 | -2.72 ± 1.75f | -1.15 ± 1.44f | 1.57 ± 0.53f |

| TBW (kg) | 36.3 ± 6.7 | 35.5 ± 6.6 | 38.0 ± 8.7 | 36.3 ± 8.4 | -0.72 ± 0.85e | -1.66 ± 0.85e | -0.93 ± 0.28f |

| FFM (kg) | 49.5 ± 9.2 | 48.5 ± 9.9 | 51.7 ± 11.8 | 49.5 ± 11.2 | -0.98 ± 1.17f | -2.21 ± 1.22e | -1.23 ± 0.40f |

| Arm lean (kg) | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 5.8 ± 2.0 | 5.6 ± 1.8 | -0.10 ± 0.27 | -0.25 ± 0.53 | -0.15 ± 0.14 |

| Trunk lean(kg) | 22.7 ± 4.1 | 22.4 ± 4.0 | 24.1 ± 5.7 | 23.1 ± 5.5 | -0.29 ± 0.75 | -1.01 ± 0.51e | -0.72 ± 0.21f |

| Feet lean (kg) | 14.9 ± 3.0 | 14.5 ± 2.9 | 15.4 ± 3.4 | 14.9 ± 3.4 | -0.45 ± 0.57f | -0.47 ± 0.35e | -0.02 ± 0.15 |

| Arm FM (kg) | 6.7 ± 3.2 | 5.3 ± 2.7 | 5.8 ± 4.0 | 5.0 ± 3.5 | -1.46 ± 1.42e | -0.78 ± 0.59e | 0.68 ± 0.36 |

| Arm fat (%) | 52.0 ± 11.1 | 47.7 ± 12.2 | 45.8 ± 17.2 | 43.9 ± 17.2 | -4.25 ± 2.62e | -1.87 ± 2.20f | 2.37 ± 0.80f |

| Trunk FM (kg) | 18.2 ± 4.2 | 16.5 ± 4.7 | 16.9 ± 4.5 | 15.5 ± 4.7 | -1.72 ± 1.35e | -1.40 ± 0.65e | 0.31 ± 0.35 |

| Trunk Fat (%) | 42.9 ± 5.5 | 40.6 ± 6.6 | 39.9 ± 8.5 | 38.6 ± 9.0 | -2.27 ± 1.89f | -1.25 ± 1.37e | 1.02 ± 0.55 |

| Feet FM (kg) | 10.9 ± 3.8 | 8.9 ± 2.9 | 9.5 ± 4.0 | 8.8 ± 3.7 | -1.93 ± 2.32f | -0.65 ± 0.54e | 1.28 ± 0.56f |

| Feet fat (%) | 40.2 ± 8.2 | 37.5 ± 8.3 | 36.4 ± 11.2 | 35.4 ± 11.3 | -2.70 ± 1.49e | -1.03 ± 1.36f | 1.67 ± 0.47e |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FFM, fat free mass; HC, hip circumference; LBM, lean boey mass; PBF, percent of body fat; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TBW, total body water; WC, waist circumference; WHR, waist-hip ratio.

aAll values are means ± SE.

bChanges post-baseline in slow weight loss group.

cChanges post-baseline in rapid weight loss group.

dChanges between groups, for normally distributed variables, paired-sample t test and independent-sample t test were used to investigate differences within and between groups, respectively. For non-normally distributed variables, the Wilcoxon signed rank and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to assess differences within and between groups, respectively.

eSignificant differences were assumed at P < 0.001.

fSignificant differences were assumed at P < 0.05.

A significant reduction in body fat (fat mass (FM), Body fat percentage, Arm fat percentage, feet FM, feet fat percentage) was observed in the slow WL group compared to the rapid WL group. In addition, a significant reduction in lean mass (lean body mass (LBM), fat free mass (FFM), Trunk lean) and total body water and RMR was seen in the rapid WL group compared to the slow WL group.

The glycemic and lipid profiles are shown in Table 3. Triglyceride and VLDL levels and insulin indices (FINS, HOMA-IR, and HOMA-S) showed a significant decrease in both groups. In addition, QUICKI increased significantly in both groups, yet no significant differences were shown between the 2 groups. Although the level of FBS and FINS changed significantly, especially in the rapid WL group, the drop in HOMA-B was not statistically significant. A significant reduction in LDL, FBS, and TC was seen in the rapid WL group. In addition, a significant reduction in HOMA-IR, HOMA-S, FBS, and LDL was seen in rapid WL group compared to the slow WL group.

| Variables | Slow Weight Loss (n = 18) | Rapid Weight Loss (n =18) | Δ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End | Baseline | End | Intragroupb | Intragroupc | Intergroupd | |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 105.9 ± 34.3 | 111.8 ± 26.5 | 120.9 ± 28.7 | 108.1 ± 27.1 | 5.91 ± 30.95 | -12.8 ± 14.4f | -18.7 ± 8.04f |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 37.8 ± 5.4 | 39.7 ± 6.2 | 43.9 ± 9.5 | 45.1 ± 6.3 | 1.90 ± 5.95 | 1.16 ± 6.08 | -0.73 ± 1.99 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 145.3 ± 65.8 | 109.6 ± 50.1 | 163.8 ± 70.5 | 118.5 ± 52.3 | -35.6 ± 45.5f | -45.3 ± 56.8f | -9.66 ± 17.17 |

| VLDL (mg/dL) | 29.0 ± 13.1 | 21.9 ± 10.2 | 32.7 ± 14.1 | 23.7 ± 10.47 | -7.11 ± 9.12f | -9.05 ± 11.37f | -1.93 ± 3.43 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 172.4 ± 40.5 | 173.5 ± 35.3 | 194.2 ± 39.6 | 176.8 ± 31.4 | 1.06 ± 33.64 | -17.4 ± 19.6f | -18.4 ± 9.1 |

| FBS (mg/dL) | 95.1 ± 11.1 | 99.0 ± 6.7 | 100.8 ± 18.8 | 95.0 ± 9.8 | 3.92 ± 10.36 | -5.87 ± 11f | -9.80 ± 3.57f |

| FINS (μIU/l) | 13.2 ± 4.7 | 11.5 ± 5.4 | 11.2 ± 4.9 | 7.6 ± 4.3 | -1.96 ± 2.52f | -3.93 ± 3.61e | -0.06 ± 1.96 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | -0.24 ± 0.6f | -0.43 ± 0.46e | -0.18 ± 049f |

| HOMA-B | 126.1 ± 26.2 | 100.7 ± 23.4 | 106.6 ± 50 | 86.9 ± 42.9 | -24.4 ± 25.8 | -18.8 ± 45.5 | 5.36 ± 41.2 |

| HOMA-S | 64.4 ± 19.5 | 79.3 ± 29.6 | 84.7 ± 48.9 | 131.7 ± 67.7 | 14.3 ± 21.2e | 44.2 ± 60.8f | 26.1 ± 35.3f |

| QUICKI | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.01 ± 0.01f | 0.03 ± 0.03e | 1.16 ± 6.08f |

Abbreviations:TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; FBS, fasting blood sugar; FINS, fasting insulin; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance; HOMA-B, HOMA-pancreatic beta cell function; HOMA-S, HOMA-insulin sensitivity; QUICKI, quantitative insulin sensitivity check index.

aAll values are means ± SD.

bChanges post-baseline in slow weight loss group.

cChanges post-baseline in rapid weight loss group.

dChanges between groups, for normally distributed variables, paired-samples t test and independent-sample t-test were used to investigate the differences within and between groups, respectively. For non-normally-distributed variables, the Wilcoxon signed ranks test and a Mann -Whitney U test were used to assess differences within and between groups, respectively.

eSignificant differences were assumed at P < 0.001.

fSignificant differences were assumed at P < 0.05.

5. Discussion

The results of the current study showed that both protocols of rapid WL and slow WL caused a reduction in waist circumference, hip circumference, total body water, body fat mass, FFM, LBM, and RMR. Greater reduction of waist circumference, hip circumference, and FFM was seen with slow WL and greater reduction of total body water, LBM, and RMR was seen with rapid WL. It seems that the effect of slow WL in maintaining body water and LBM (as a metabolic tissue) was more significant than rapid WL.

In previous studies, elevated ratio of myostatin-to-follistatin, as an indicator of skeletal muscle catabolism, was reported to be greater in rapid WL compared to slow WL (25). The results were consistent with other studies in this field (26). In a study by Martin et al., the impact of these 2 protocols had been compared on the indices of anthropometric and lipid profiles. Their study was conducted in the form of a pilot study on obese postmenopausal females. The results of their study showed that slow WL caused more fat mass reduction and less FFM loss. However, in their study, no differences in lipid profile were observed between slow WL and rapid WL (18).

No significant changes were observed in systolic and diastolic blood pressure in any of these 2 diets, although a non-significant reduction in average blood pressure at the end of the study was observed in both groups. It seems that the effects of weight-loss diets on the decrease of blood pressure was more concrete in people with hypertension (27). Consistent with the current study, several studies did not support the impact of WL on blood pressure in people, who had normal blood pressure (16, 28).

The current study showed that both protocols of WL could improve components of the lipid and glycemic profiles. In addition, in this study it was found that with the same amount of WL, the impact on reducing levels of FBS and LDL, and improvement of insulin resistance and sensitivity was greater with rapid WL. Positive effects of rapid WL on metabolic factors were reported in several studies.

Consistent with the current study, recent findings indicate that slow weight loss, as recommended by current guidelines, worldwide, is not a priority over rapid weight loss. Purcell et al. in a clinical trial studied the effect of weight loss rate and weight management. Their results showed that in the long-term, with rapid weight loss (450 to 800 Kcal/day) than gradual weight loss (500 kcal less than the daily requirement), the weight loss is faster and more stable. The researchers suggested that the limited carbohydrate intake of very-low-calorie diets might promote greater satiety and less food intake by inducing ketosis. Losing weight quickly may also motivate participants to persist with their diet and achieve better results (29).

Evidence suggests that rapid weight loss through improvements in markers of oxidative stress could improve metabolic factors. Tumova et al. reported that rapid weight loss (800 kcal daily consisting of liquid beverages) could, through reducing oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) cause a decrease in total cholesterol. In addition, rapid weight loss could, through reducing the activity of Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2), cause a decrease in levels of LDL-C, TC, and insulin in people with metabolic syndrome (30). Roberts et al. also reported that short-term diet (21-Day) and exercise intervention for males with metabolic syndrome factors could, through reducing level of inflammatory markers, such as myeloperoxidase (MPO), cause improvement in lipid risk factors and HOMA-IR (30).

Consistent with the current study, improvement of metabolic factors after 4 weeks of VLCD was reported in a study by Erik et al. In this study, it was found that VLCD in the short-term intervention could cause a significant reduction in the levels of blood glucose, cholesterol, and TG in a fasting condition (27). The study of Laaksonen et al. showed that administration of VLCD diet for 5 weeks improved metabolic factors and decreased cutaneous water loss and increased subcutaneous fat water. This researcher suggested that WL and consequent improved insulin sensitivity could mediate an increase in abdominal subcutaneous fat hydration (31).

The results suggest that WL could improve anthropometric status and lipid and glycemic profiles regardless of calorie restriction and the speed of WL. However, there could be some differences between the 2 protocol types of WL in terms of impact. The WL regardless of its severity could improve anthropometric indicators, although body composition is more favorable following a slow WL. Both diets improved lipid and glycemic profiles. In this context, rapid WL was more effective.

Many studies have suggested that rapid weight loss may serve as a risk factor for later weight regain. Thus, a limitation of the current study was that it did not evaluate weight regain.