1. Background

In December 2019, several cases of unknown pneumonia, later called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), were reported in Wuhan, China. Based on investigations, this highly infectious respiratory disease was caused by a novel RNA beta-coronavirus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (1, 2). On March 24, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic due to its rapid global prevalence and dominance as a health problem causing high morbidity and mortality in a short period (3). In Iran, the first confirmed patient with COVID-19 was reported in Qom province on February 19, 2020 (4). Afterward, Iran turned into one of the pandemic epicenters (5). Among patients with COVID-19, those having comorbidities, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases, had significantly poorer health outcomes (6). More characteristically, the global quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected access to healthcare, including for patients with chronic diseases such as children with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) (7-9). The emergence of T1DM symptoms usually occurs quickly in children. Since diabetes ketoacidosis (DKA) is mainly caused by a delay in diagnosis and initiation of insulin therapy (10), the early diagnosis of T1DM is crucial in preventing the disease progression towards DKA, which is an acute, life-threatening complication of diabetes (11). The frequency and severity of DKA in children with T1DM are increasing in Germany, the USA, and UK, Italy, China, and Spain (12-18).

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to compare the frequency and severity of DKA in children admitted to Yazd Shahid Sadoughi Hospital before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out among ≤ 18-year-old children with diagnosed DKA admitted to the main referral center of Yazd Shahid Sadoughi Hospital from February 20, 2020, to November 21, 2021 (pandemic period). Later, the findings were compared with the data obtained from children hospitalized during the same period in 2018 and 2019 (pre-pandemic). The patients discharged from the hospital with personal satisfaction were excluded.

The data were reviewed, and the related information, including the patient's age, gender, arterial blood gas, length of hospital stay, diabetes type, serum electrolytes, ketones present in urine, DKA duration, self-reported symptoms such as polyuria, polydipsia, abdominal pain, weight loss, nausea/vomiting, alerted mental status, fever, and also COVID-19 PCR test results were extracted from the medical records. Diagnosis of COVID-19 was based on clinical presentation and positive PCR test. Furthermore, patients with DKA were included in the study based on their medical history, examinations, and laboratory criteria.

To this end, DKA was defined as venous pH < 7.35 and categorized as mild (pH level 7.25 - 7.35 and CO2 level 16 - 20 mEq/L), moderate (pH level 7.15 - 7.25 and CO2 level 10 - 15 mEq/L), and severe (pH level < 7.15 mmol/L and CO2 level less than 10 mEq/L) (19).

3.1. Ethics

This study was approved by the Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences' ethics committee (ethics certificate number: IR.SSU.REC.1400.221).

3.2. Statistical Analysis

The data analyses of DKA patients who met the study's inclusion criteria were conducted using SPSS 25.0 statistical program. The following descriptive statistics were calculated: Mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and the frequencies and numbers for categorical variables. The Mann-Whitney U test compared continuous variables, and the chi-square test was used for categorical variables. The results are shown as means with standard deviation. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

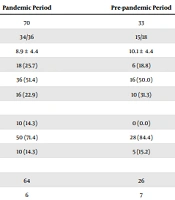

The data collected from 70 children (34 males, 48.6%, 36 females, 51.4%) diagnosed with DKA during the pandemic were compared with the information obtained from 33 children (15 males, 45.5%, 18 females, 54.5%) during the pre-pandemic period. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with DKA are outlined in Table 1.

| Parameter | Pandemic Period | Pre-pandemic Period | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 70 | 33 | |

| Sex (F/M) | 34/36 | 15/18 | 0.467 |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | 8.9 ± 4.4 | 10.1 ± 4.4 | 0.219 |

| 1 - 5 | 18 (25.7) | 6 (18.8) | |

| 6 - 12 | 36 (51.4) | 16 (50.0) | |

| 13 - 18 | 16 (22.9) | 10 (31.3) | |

| Duration of admission (days) | 0.348 | ||

| < 2 | 10 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2 - 5 | 50 (71.4) | 28 (84.4) | |

| > 5 | 10 (14.3) | 5 (15.2) | |

| Duration of DKA (days) | 0.072 | ||

| ≥ 1 | 64 | 26 | |

| < 1 | 6 | 7 | |

| Polyuria | 58 (82.9) | 20 (60.6) | 0.015 |

| Polydipsia | 58 (82.9) | 20 (60.6) | 0.015 |

| Weight loss | 29 (41.4) | 23 (69.7) | 0.035 |

| Abdominal pain | 33 (47.1) | 23 (69.7) | 0.026 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 39 (55.7) | 21 (63.6) | 0.294 |

| Fever | 16 (22.9) | 5 (15.2) | 0.264 |

| Alerted mental status | 14 (20.0) | 8 (24.2) | 0.402 |

| Blood sugar, mean | 429.8 ± 121.3 | 415.5 ± 129.1 | 0.592 |

| pH, mean | 7.09 ± 0.17 | 7.12 ± 0.16 | 0.214 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L), mean | 6.28 ± 4.42 | 7.43 ± 3.42 | 0.031 |

| CO2, mean | 17.59 ± 8.20 | 20.50 ± 7.03 | 0.021 |

| Ketone urine | 0.894 | ||

| 1+ | 17 (24.2) | 4 (12.1) | |

| ≥ 2+ | 53 (75.7) | 29 (87.8) | |

| DKA severity (n) | 0.206 | ||

| Severe DKA | 25 (35.7) | 7 (21.2) | 0.138 |

| Moderate DKA | 26 (37.1) | 12 (36.4) | 0.939 |

| Mild DKA | 19 (27.1) | 14(42.4) | 0.121 |

Abbreviations: DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; SD, standard deviation.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

During the pandemic (51.4%) and pre-pandemic (50.0%) periods, most children diagnosed with DKA were aged 6 - 12 years. Moreover, 71.4% and 84.4% of the participants stayed in hospitals for 2-5 days during and before the pandemic, respectively.

Children with new-onset T1DM during the COVID-19 pandemic (44.7%) was remarkably higher than in the pre-pandemic period (12.6%) among children with DKA (P = 0.012). Regarding the DKA severity, 35.7% vs. 21.2% were severe, 37.1% vs. 36.4% were moderate, and 27.1% vs. 42.4% were mild. In other words, significantly more severe DKA cases were found during the pandemic than before (35.7% vs. 21.2%), while the frequency of moderate DKA cases was not noticeably different in the two periods (37.1% vs. 36.4%). During the pandemic, the most frequently observed symptoms in hospital admission records were polyuria (82.9%) and polydipsia (82.9%), reported in more than 80% of children. In contrast, the most frequent pre-pandemic symptoms were abdominal pain (69.7%) and weight loss (69.7%).

Patients had substantially lower bicarbonate levels during the pandemic than before (6.28% vs. 7.43%, respectively).

Of 70 children with DKA, 30 patients were tested for COVID-19 since they had suspected symptoms of COVID-19 infection or their family members were infected. The test results were positive for six children, but the symptoms were mild among five patients with normal chest X-rays and blood oxygen saturation. Only one of the patients had been hospitalized for 10 days with signs of respiratory distress, polyuria, and polydipsia. Although all his physical examination results were normal, his chest examination was the main challenging problem (20). Out of 33 patients with suspected symptoms of COVID-19, the C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 26 patients was 1+, and the rest were 2+. Also, the level of lymphocyte count in these patients was 24.91 ± 13.74 cells/mm3.

5. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the severity and frequency of DKA during the COVID-19 pandemic with those of the same pre-pandemic period in Iran. Based on the findings, a remarkable increase was found in the prevalence of DKA in children during the pandemic. A similar German study indicated that the incidence of DKA was higher among children with T1DM during the COVID-19 pandemic than in the same period of the previous year when there was no pandemic (15). A multicenter study among 88 diabetes centers in the United Kingdom from March 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020, reported an apparent increase in the incidence of DKA compared to the same period in the previous five years (17). However, a study conducted in Italy showed no differences in the incidence of DKA during and before the pandemic (13). Beliard et al. declared that the diagnosis of COVID-19 did not significantly affect the presentation of DKA in children with T1DM (18). Similar to other reports from other countries, the higher rates of DKA in our study can be attributed to factors such as focusing on COVID-19 clinical manifestation. Additionally, some parents may have avoided seeking medical care for children with mild symptoms due to their fear of infection with COVID-19 in the hospital (7, 12). The present study performed PCR tests for 30 children during the COVID-19 pandemic, with six positive tests. Five children had mild symptoms, but one had signs of respiratory distress (20).

Similar to any scientific work, the present study has some limitations. In this retrospective study, we did not collect information on the onset time of symptoms. So, no data were available on the patients' disease status at DKA diagnosis. Furthermore, since all participants did not undergo the COVID-19 PCR test, some children may have been asymptomatic and not tested for COVID-19. Such limitations could have affected our findings on the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the prevalence and incidence of DKA in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, throughout the period of SARS-CoV-2 exposure, fear of infection with COVID-19 and late referral to health centers may have caused a delay in the diagnosis of DKA and increased the number of patients referred to the hospitals during the pandemic. Notably, the hospitals' facilities and services prepared for the patients were approximately the same. So, these issues had negligible limitations during the COVID-19 period.

In conclusion, our findings revealed that COVID-19 could affect children with or without direct infection. This disease also increased the DKA frequency and severity more significantly than in the pre-pandemic years when no pandemic existed. The delayed diagnosis of DM can be explained by numerous factors, including local restrictions, quarantines, fear of infection with COVID-19 in hospitals, and the parents' stress about their children. These results illustrate the necessity of encouraging children and their parents to continue seeking and receiving healthcare services during the pandemic. Further studies and more efforts are required to enhance early diagnosis, increase the public's awareness, and perform the needed interventions timely.