1. Background

Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine-related malignancy worldwide. This cancer makes up 1.3% of all cancers and causes about 0.5% of cancer-related deaths each year around the world. Although the mortality of differentiated thyroid cancer is relatively low, the rate of disease relapse or persistence is high, leading to increased morbidity (1).

In the recent decades, thyroid cancer incidence has rapidly increased all over the world (2-5). It is unknown whether this rise in thyroid cancer is due to increased use of thyroid sonography and sono-guided fine needle aspiration cytology examination or whether this is due to a true rise in thyroid cancer from an undetermined etiology. Incidence of large tumors has increased as well. Furthermore, despite earlier diagnosis and better treatment for thyroid cancer, the mortality caused by this illness has not only been diminished, but has also increased (6, 7). Thus, additional factors other than early detection may contribute. Currently, risk factors for thyroid cancer include previous childhood radiation to the head and neck, family history of thyroid cancer, exposure to ionizing radiation (8), inadequate or excess iodine intake (9), which are well known but none of them can justify an increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer. Recently, other factors, such as diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome (10, 11), insulin resistance (12), chemical toxins (13, 14), and dietary factors (15, 16) have been reported as potential risk factors of thyroid cancer.

In a similar trend with thyroid cancer, the prevalence of obesity and as a result, insulin resistance has increased in the recent decades (17). Although the precise molecular mechanism responsible for increasing the incidence of thyroid cancer is not well defined, it may be possible to attribute some of these carcinogenic effects to insulin resistance. Insulin resistance results in hyperinsulinemia. Increased levels of insulin reduce the production of Insulin-like growth factor-1 binding proteins (IGFBPs) and this leads to increased levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-I) in the blood. The IGF-I displays potent antiapoptotic, cell-survival, and transforming activities (18).

However, information on the role of insulin resistance in differentiated thyroid cancer is limited. To the best of our knowledge, there are only 2 studies about the role of insulin resistance in DTC formation. In one study, insulin resistance was more prevalent in 27 female patients with DTC in comparison with the control group (12). In another study, Forty-one patients with DTC were compared with the control group. The difference between groups with regards to homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), the frequency of insulin resistance (IR) and body mass index (BMI) was not significant (19).

Due to limited information, this study aimed at further evaluating the association between insulin resistance and differentiated thyroid cancer as well as the role of this parameter as a potential novel risk factor in thyroid cancers.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

This case-control study was carried out on 30 euthyroid patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma. The inclusion criteria were 1) euthyroidism (20, 21) (normal thyroid function was defined as normal thyroid stimulating hormone [TSH: 0.4 - 4.2 mIU/L], normal free thyroxine [FT4: 0.8 - 1.8 ng/dL] and normal triiodothyronine [FT3: 2.3 - 4.2 pg/mL] levels); 2) thyroid nodules ≥ 1 cm; 3) negative titers of anti-thyroid antibodies (anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody < 16 IU/mL and anti-thyoglobulin < 100 IU/mL); 4) malignant cytology according to Bethesda system classification (suspicious for malignancy or malignant).

Individuals with any of the following characteristics were excluded from the study: subjects with a history of thyroid disease, previous thyroid medication therapy at any time, overt or subclinical hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, history of neck irradiation or thyroid surgery, iodinated contrast material exposure in the previous 6 months, smoking, statin and antihypertensive therapy. Individuals were also excluded if they had a personal or family history of diabetes mellitus, endocrine obesity, hepatic or renal failure, schizophrenia, convulsion, and depression, which could have an impact on thyroid function tests. Pregnant and lactating females also accounted for exclusion from the study.

Thirty-four newly diagnosed patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma based on fine needle aspiration cytology, who live in an iodine-sufficient area (22), attended the outpatient endocrinology clinic of Zahedan city, southeast of Iran. These patients were chosen as the potential study population between June 2014 and July 2016. Among them, 2 patients were excluded due to positive thyroid antibodies, and 1 patient due to subclinical hypothyroidism and 1 because of pregnancy. In all patients with positive cytology, permanent pathology confirmed the diagnosis. Finally, 30 newly diagnosed patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma were consecutively chosen as the patient group.

For each of the 30 patients of the case group, a pair was selected from hospital staff based on matching protocol; they were individually matched according to gender, age (± 1 year) and BMI (± 1). Fasting plasma glucose was measured for ruling out diabetes mellitus in the control group. Thyroid function tests and thyroid ultrasonography were performed in all participants. Thus, 30 healthy euthyroid control participants were chosen with normal thyroid sonography. Individuals with any known acute or chronic illness were excluded.

Finally, 30 pairs were obtained considering the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. The Zahedan University ethics committee for human studies approved the protocol (ethical code number: 92-5988). All participants provided an informed consent.

2.2. Anthropometric Measurements

Body weight (kg) was measured without shoes, using digital scales, and height (cm) was measured in a standing position without shoes. Body Mass Index was calculated based on the weight (Kg)/height (m)2.

2.3. Biochemical Evaluations

All blood samples were taken between 8:00 and 9:00 in the morning and after 12 hours of fasting. Samples were stored at -70°C until the day of the test. Serum glucose was measured using the glucose oxidase technique. Intra-assay CV was 1.0% and inter-assay CV was 4.7%. Serum insulin was evaluated using solid-phase the competitive chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (Diagnostic Product LIAISON, Italy) method. Inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 7.39%.

Measured serum insulin and fasting plasma glucose was applied to calculate steady state beta cell function (%B), insulin sensitivity (%S), and insulin resistance (IR) for normal and pre-diabetic participants by using the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA2) calculator (University of Oxford, web site; http://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/homacalculator/index.php). A HOMA index equal or higher than 2.5 denotes insulin resistance (23-25).

Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) was evaluated by using the immunoradiometric assay (Diagnostic Products LIAISON, 2011, Italy) with a reference range from 0.4 to 4.2 mIU/L. The intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 1.5%. The corresponding inter-assay CV was 2.3%. Free triiodothyronine was measured using immunochemoluminescent assays by an automated analyzer (Diagnostic Products LIAISON, 2011, Italy) with a reference range from 2.3 to 4.2 pg/mL. The intra-assay CV was 5.16% and inter-assay CV was 7.9%. Free thyroxine was also measured using immunochemoluminescent assays by an automated analyzer (Diagnostic Products LIAISON, 2011, Italy) with a reference range from 0.8 to 1.8 ng/dL. The intra-assay CV was 3.4% and inter-assay CV was 3%.

Antithyroid peroxidase (normal range < 16 U/mL) and antithyroglobulin (normal range < 100) was measured by immunochemoluminescent assays employing commercial kits (Diagnostic Products LIAISON).

2.4. Thyroid Ultrasound

Thyroid sonography was performed for all participants by a sonologist using a 7.5-MHz linear probe (Aloka Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). All patients with thyroid nodules larger than 1 cm were evaluated by fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB). In the control group, there was no nodule with any size.

2.5. Cytology

All FNAB samples were evaluated by an experienced pathologist. The cytology was reported as malignant nodules, according to the Bethesda system in all cases. Patients with diagnosis of thyroid cancer or suspicious of having it were included. Permanent pathology confirmed the diagnosis.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

By studying 30 case and 30 control participants, an unmatched study had a 95 % power to detect a mean difference in HOMA-IR value of 1.6 between case and control groups at the 5% significance level, assuming standard deviation of HOMA-IR value to be 1.7 (14) (so the standardized mean difference would be about 1 SD, which is clearly considered as a clinically important effect size) (26). As the study is matched on strong confounders, such as age and gender, the sample size required for a matched study is indeed expected to be lower than that required for the unmatched study. Thus, the power of the current matched study should be greater than 95% (27-29). Continuous variables were presented as mean (standard deviation) and categorical variables as counts (percentage).

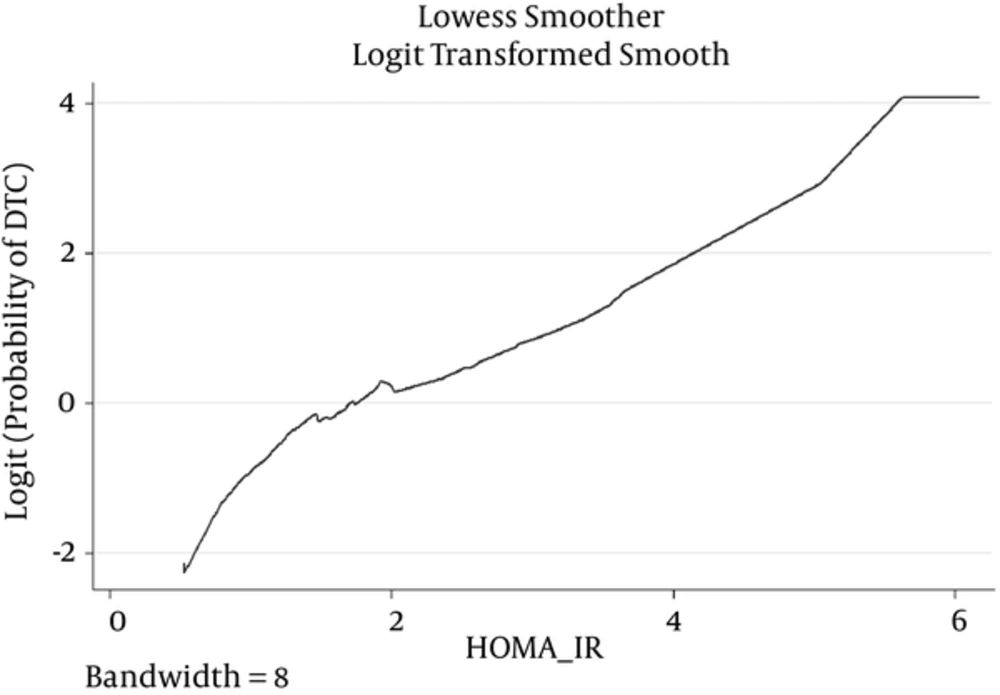

The researchers used conditional logistic regression to estimate the odds ratios (with 95% confidence interval) between HOMA-IR and differentiated thyroid cancer adjusted for matched confounders including age, gender, and BMI. Fractional polynomials and locally weighted scatter plot smoothing (LOWESS) algorithm were used to determine the appropriate scale of continuous variables in models.

Pair-matched analysis only relies on discordant pairs (exposed case-unexposed control and unexposed case-exposed control) and these involve small counts in our study as the sample size is not large, and more importantly the prevalence of exposure is very high or very low. Therefore, the standard conditional logistic regression analysis is susceptible to sparse-data bias. Following Greenland et al. the researchers performed penalized conditional logistic regression using a F(2,2) prior for the matched odds ratio (29-31). The F(2,2) prior encodes the 95% prior odds ratio interval of 1/39 to 39. To apply F(2,2) prior, the researchers augmented the original dataset with 2 sets of discordant pairs: one containing an exposed case and an unexposed control and the other with an unexposed case and an exposed control. This is the case for binary variable: insulin resistance (1: HOMA-IR ≥ 2.5, 0: HOMA-IR < 2.5). For the continuous variable HOMA-IR, the researchers centered the variable (subtracted the mean) so that 0 and 1 are meaningfully different values for the covariate. Based on the suggestions of Greenland et al. this study presented 95% profile-likelihood confidence intervals for odds ratios along with P values based on likelihood-ratio tests (30, 31). All analyses were done by Stata version 12 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

3. Results

The study included 30 patients and 30 controls matched to the cases based on age, gender, and BMI, in pairs. In the patient group, 24 (80%) cases were female and 6 (20%) were male. The mean (SD) age was 34.40 (12.73) years old in the patient group and 33.79 (12.93) in the control group. The mean BMI was 26.1 in both groups. Serum concentrations of FT4, FT3, TSH, Anti-TPO, and Anti-Tg were within the normal range and there was no significant difference between case and control groups. The mean FT4 level was higher in the case group compared to the control group (Table 1).

| Variables | Case Group (n = 30) | Control Group (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (female), n (%) | 24 (80) | 24 (80) |

| Age, y | 34.4 (12.7) | 34.1 (12.8) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.1 (5.4) | 26.1 (5.3) |

| TSH, mIU/L | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.1) |

| FT4, ng/dL | 1.2 (0.32) | 0.95 (0.12) |

| FT3, pg/mL | 2.5 (0.73) | 2.7 (0.35) |

| TPOAb, IU/mL | 5.6 (4.0) | 4.6 (4.3) |

| TgAb, IU/mL | 21.2 (20.4) | 18.4 (28.3) |

Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics of Study Subjectsa

As depicted in Table 2, the mean fasting plasma glucose, fasting plasma insulin, and HOMA-IR were higher in the case than in the control group. Insulin resistance was more prevalent in the case group than the control group (43.3% versus 13.3%). Insulin sensitivity index was lower in the case group than in the control group (50 and 81, respectively).

| Variables | Case Group (n = 30) | Control Group (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL | 101.5 (9.2) | 97.4 (7.9) |

| Fasting insulin, µu/mL | 18.7 (10.8) | 11.2 (5.9) |

| HOMA-IR | 2.4 (1.4) | 1.5 (0.76) |

| Insulin resistance, n (%) | 13 (43.3) | 4 (13.3) |

| Beta cell function, % | 138.7 (47.0) | 110.4 (37.7) |

| Insulin sensitivity index, % | 50.0 (22.2) | 81.0 (45.2) |

Homeostasis Model Assessment Parameters of Study Subjectsa

Correlation of PTC size with clinical and laboratory parameters is shown in Table 3.

| Variable | DTC Size | |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation R-Value | P Value | |

| BMI | 0.12 | 0.52 |

| Age | 0.11 | 0.54 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.25 | 0.17 |

| Beta cell function | -0.10 | 0.57 |

| Insulin sensitivity index | -0.15 | 0.41 |

| TSH | 0.16 | 0.39 |

| FT4 | -0.10 | 0.58 |

| FT3 | -0.03 | 0.84 |

| TPOAb | 0.20 | 0.26 |

| TgAb | 0.08 | 0.64 |

Correlation of DTC Size With Clinical and Laboratory Parameters in the Patient Group

There were 11 discordant pairs with exposed (HOMA-IR ≥ 2.5) cases and 2 discordant pairs with unexposed (HOMA-IR < 2.5) cases, so the ordinary matched odds ratio is 11/2 = 5.5.

A positive correlation was observed between serum HOMA-IR levels and differentiated thyroid cancer (OR: 2.43 for 1 unit increase in HOMA-IR, 95 % CI: 1.35 - 5.51; P = 0.001). Insulin resistance was significantly associated with differentiated thyroid cancer (penalized OR: 4, 95 % CI: 1.27 - 17.56; P = 0.016). Note that penalization using F(2,2) prior shrinks the ordinary matched OR to 1 by adding one to each of the discordant pairs, i.e. penalized OR= (11 + 1)/(2 + 1) = 4.

Figures 1 shows the Lowess regression curves for the associations between HOMA-IR and DTC. Figure 1 suggests that including HOMA-IR as a linear term in the logistic regression model provides a descent fit.

4. Discussion

In this study, the researchers investigated the association between HOMA parameters and differentiated thyroid cancer in an Iranian population. The study suggested that insulin resistance is more prevalent in patients with DTC. As revealed earlier, the researchers classified participants to 2 groups based on HOMA-IR value in the present study. The odds of DTC in the subjects with insulin resistance (HOMA-IR ≥ 2.5) was significantly (4-fold) higher than that of the subjects with HOMA-IR < 2.5. These results showed an association between IR and differentiated thyroid cancer.

Recently a controversial topic in the field of thyroid disease is the association of IR with thyroid nodule and goiter. These studies have reported the association of IR and thyroid morphological changes (32-37). However, there is limited data on the association between IR and thyroid cancer (12, 19). The current study results are consistent with the results of Rezzonico’s study. In this study, insulin resistance was observed in 50% of patients with DTC and only in 10% of the control group (12). In contrast, in Balkan’s study, no association was found between IR and thyroid carcinoma (19).

In the recent decades, the incidence of thyroid cancer has increased throughout the world (38-40). In a similar manner, prevalence of insulin resistance in parallel with obesity has increased in the recent years. Insulin resistance is a pathognomonic characteristic of subjects with metabolic syndrome, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, polycystic ovarian disease, and pre-diabetes. Insulin resistance is characterized by an inadequate physiological response of peripheral tissues to insulin, which leads to hyperinsulinemia (41). Increased insulin levels, decrease the production of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) binding proteins and increase levels of free IGF-1. The IGF-I displays potent antiapoptotic, cell-survival, and transforming activities. It has been observed that IGF-1 and its receptor are overexpressed in differentiated thyroid cancers suggesting that overexpression of these factors may contribute to thyroid tumorigenesis (18, 42). Insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway is involved in modulation of thyroid gene expression, thyrocyte proliferation, differentiation, and malignant transformation (43, 44). IGF-1, IGF-2, IGF-1 receptor, and insulin receptor isoforms are over-expressed in thyroid cell precursors and obviously decreased in differentiating thyroid cells. Increased levels of insulin and IGF-I in the bloodstream increase the growth of the progenitor cells in the thyroid carcinoma (45). Genetic events, such as point mutation, generate an activation of the MAPK pathway, which usually induces cell proliferation and dedifferentiation (46, 47). It is probable that increased insulin levels due to hyperinsulinemia might also stimulate this MAPK pathway, thyroid proliferation and, finally, development of thyroid cancer.

Thyroid Stimulating Hormone is the most important factor regulating the growth and differentiation of thyroid cells and is a known mitogen in the presence of insulin in cell cultures. Furthermore, TSH could also reduce the apoptosis process in response to various factors (48). In the present study, the serum TSH level was not significantly different between the 2 groups and was within the normal range. Therefore, the results of this study are not explained with TSH.

Carcinogenesis is a complex process and some other pathologic mechanisms, such as vitamin D deficiency, variation in deodinase expression, and chronic inflammation, may play a role during thyroid carcinogenesis (49-51).

The present study had several limitations. First was the relative small number of participants. To reduce the sparse-data bias, the researchers performed a penalized conditional logistic regression analysis with a weekly informative prior (30, 32, 52). Second, selecting controls from the hospital staff may introduce selection bias. However, the exact source population of the cases in this study is difficult to specify, and any choice of controls only approximates the actual population. Third, this study was a cross-sectional observational study that cannot naturally establish the causal relationship between insulin resistance and thyroid cancer. Fourth, the glucose clamp method, the gold standard test, was not used, which is invasive and costly; instead, HOMA-IR was used as a surrogate measure of insulin resistance. In this regard, there is an acceptable correlation between results of insulin resistance based on HOMA and the euglycemic clamp. Thus, HOMA-IR is widely used in clinical and epidemiological studies to measure insulin resistance (53, 54).

Having a control group with no thyroid nodules, assessment of cytological and histopathological outcome of each thyroid nodule, anti-thyroid antibodies measurement, and matching of age, gender and body mass index were potential advantages of this study.

In conclusion, insulin resistance is more prevalent in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer and shows a significant association. Conducting studies with larger sample sizes and prospective design could enhance the power of future studies in this area. Further studies are needed to determine the contribution of this factor in thyroid cancer incidence.