1. Introduction

Graves’ disease is characterized by hyperthyroidism, goiter, orbitopathy, and occasionally dermopathy. The symptoms of a goiter range from an asymptomatic cervical neck mass to local compression causing dyspnea, dysphagia, and hoarseness (1). Rarely, a substernal nontoxic goiter can cause venous compression of the mediastinal structures, including superior vena cava syndrome (2). Nevertheless, chylothorax in Graves’ disease caused by a substernal goiter or a nontoxic substernal goiter is very rare (3, 4).

Chylothorax is an accumulation of chyle in the pleural space due to interruption of the thoracic duct or its tributaries. The pleural fluid typically has a high triglyceride content and a turbid or milky white appearance. It is usually caused by malignant neoplasms, surgery, or trauma (5). In association with thyroid disease, it has frequently been reported after neck dissection for thyroid cancer surgery (6-8). The treatment of chylothorax can be classified into three approaches: treating the underlying disease, conservative management including fasting, total parenteral nutrition (TPN), medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) supplements, and chest tube draining, and surgery (5, 9). When conservative therapy fails or in cases of traumatic chylothorax, surgical therapy such as thoracic duct ligation or pleuroperitoneal shunting is recommended (9).

Although compressive symptoms are a common indication for thyroidectomy, we report a rare case of chylothorax associated with a substernal goiter in Graves’ disease treated with radioactive iodine.

2. Case Description

A 23-year-old woman was referred to our clinic with dyspnea and a massive pleural effusion. She had been diagnosed with Graves’ disease 6 years earlier. However, she did not take her anti-thyroid medications because of a fear of weight gain and because of an improvement in her symptoms. On presentation, she had a 2-week history of worsening shortness of breath and left pleuritic chest pain. At presentation, her blood pressure was 130/60 mmHg, with a regular heart rate of 138 beats/min and body temperature of 36.5°C. She had characteristic bilateral proptosis and a diffuse goiter. Her thyroid was diffusely enlarged and was non-tender. Both jugular veins were distended. Breathing sounds were decreased in the left lung, but there was no wheezing.

On admission, the complete blood count, electrolytes, and liver and renal function tests were normal, but her total cholesterol level was decreased (75 mg/dL). Thyroid function tests showed severe hyperthyroidism: serum triiodothyronine 501.1 (normal 79.8 - 200) ng/dL, free thyroxine 4.62 (normal 0.75 - 2.00) ng/dL, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) 0.00 (normal 0.3 - 5.0) μIU/mL. TSH receptor and anti-thyroperoxidase antibodies were markedly increased at > 40 (normal 0 - 1.5) IU/L and > 3000 (normal: 0 - 60) U/mL, respectively.

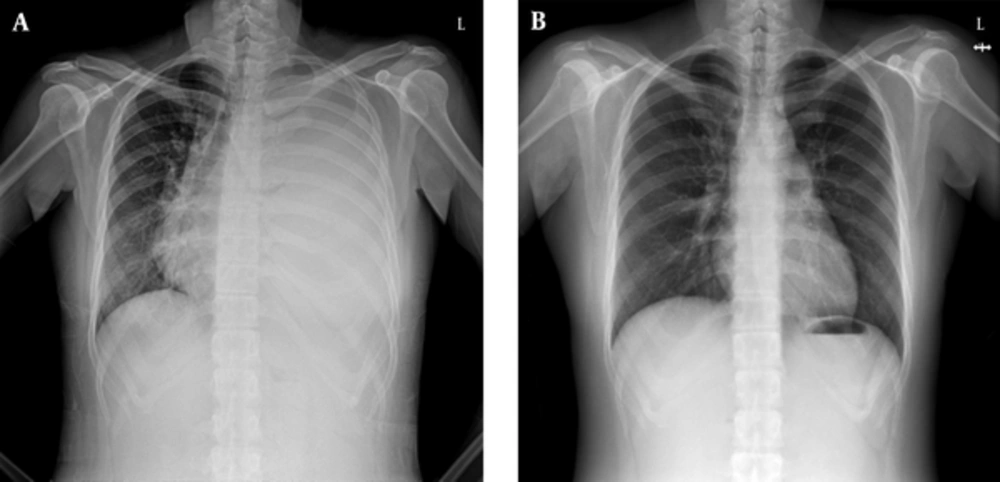

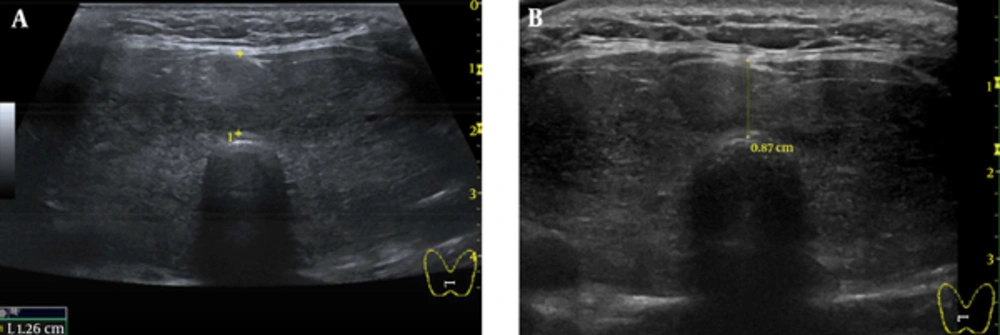

A chest X-ray showed increased opacity in almost the entire left lung (Figure 1A). Chest computed tomography (CT) showed a left pleural effusion with passive atelectasis. Ultrasonography of the thyroid revealed a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland to approximately 61 cm3 (3.4 × 2.4 × 6.8 cm, width × depth × length) without definite evidence of nodular lesions (Figure 2A).

Thyroid volume was calculated by the formula (10):

V (mL) = π x depth (D) x width (W) x L (length) (cm)

Neck CT showed diffuse enlargement of the thyroid gland with an intrathoracic goiter and retrosternal extension of the Both lower pole. Diagnostic thoracentesis produced milky, turbid pleural fluid. Analysis of the pleural fluid showed an elevated triglyceride (TG) level (883 mg/dL) and lymphocyte-predominant white blood cells (cell count 1,346/mL; lymphocytes, 95%). Biochemical studies of the pleural fluid were consistent with chylothorax. Microbiological cultures and cytological analysis of the pleural fluid were negative for infection or malignancy.

Her symptoms and signs improved after placing a chest tube and treating her with methimazole and propranolol. She fasted via TPN for 5 days. However, we stopped the TPN when she complained of extreme hunger and chest pain at the tube site and was started on a high-protein, low-fat diet (< 10 g fat/day) supplemented with oral MCT. After starting this diet, thoracic pleural fluid drainage increased (up to 500 mL/day). Lymphangiography with post-procedure CT scanning was performed to identify the exact site of leakage. However, no abnormal findings were observed on 99 mTc-phytate lymphoscintigraphy performed to identify the exact site of the chyle leakage.

Two weeks after admission, we decided to administer radioactive iodine (RAI) to reduce the goiter size and treat the Graves’ disease, because the patient refused surgical therapy. The patient was discharged after 20 mCi (740 MBq) RAI therapy and concomitant steroid prophylaxis for ophthalmopathy with an indwelling catheter for drainage at home and methimazole medication. Two weeks after discharge, although a chest x-ray showed a left pleural effusion, we removed the indwelling catheter because there had been no further re-accumulation of chyle. She had no symptoms of thyrotoxicosis or dyspnea 4 weeks after discharge. A follow-up chest x-ray 4 weeks post RAI therapy showed no residual chylothorax (Figure 1B). On physical examination, the goiter was decreased slightly. Ten weeks after RAI therapy, a follow-up ultrasonography of the thyroid showed a decreased size of diffuse goiter compared initial ultrasonography (36 mL volume of both thyroid gland, 2.8 × 2.0 × 6.1 cm, width × depth × length, 0.87 cm, isthmus thickness) (Figure 2B).

A, Ultrasonography of the Thyroid Revealed a Diffusely Enlarged Thyroid Gland to Approximately 61 mL (3.4 × 2.4 × 6.8 cm, Width × Depth × Length, 1.26 cm, Isthmus Thickness) Without Definite Evidence of Nodular Lesions; B, Ten Weeks After RAI Therapy, a Follow-Up Ultrasonography of the Thyroid Showed a Decreased Size of Diffuse Goiter Compared to Initial Ultrasonography (36 mL Volume of Both Thyroid Gland, 2.8 × 2.0 × 6.1 cm, Width × Depth × Length, 0.87 cm, Isthmus Thickness).

3. Discussion

We reported a rare case of chylothorax associated with a substernal goiter in Graves’ disease treated with radioactive iodine. Although the standard treatment for the compressive symptoms caused by a large goiter is surgical therapy, medical or RAI treatment has also been used (10). After RAI therapy, it may take several months to achieve a significant reduction in the goiter volume, although the chylothorax and goiter improved rapidly in our case.

Chylothorax is defined as the accumulation of chyle containing high TG levels in the pleural space. It usually results from obstruction or disruption of the lymphatic drainage by a malignant neoplasm, surgery, or trauma. The definitive diagnostic test for patients suspected of having chylothorax is analysis of pleural fluid collection by thoracentesis. The pleural fluid TG level is key to diagnosing suspected chylothorax, i.e., a pleural fluid TG level > 110 mg/dL (1.24 mmol/L) with a cholesterol level < 200 mg/dL (5.18 mmol/L) (11). Lymphangiography with post-procedure CT may be used to identify the exact site of leakage (12). In this case, 99mTc-phytate lymphoscintigraphy was performed, because it is less invasive than lymphangiography.

Two retrospective studies have examined the causes of chylothorax (5, 12). In association with thyroid disease, traumatic chylothorax has occasionally been reported after neck dissection for thyroid cancer surgery (6-8). However, nontraumatic chylothorax associated with a substernal goiter has been reported rarely (3, 4, 13). A possible mechanism of chylothorax is external compression of the thoracic duct along its course (6). An intrathoracic goiter can compress the thoracic duct if it has marked posterior and inferior extension into the thoracic inlet (4), which was the case for the intrathoracic goiter in our patient, and this was considered the cause of the chylothorax.

The treatment of chylothorax can involve treating the underlying disease, conservative management, and surgery (9). Conservative treatment involves replacing the nutrients lost in the chyle and draining the chylothorax using a chest drain (5). If the chyle leak is not reduced following the use of MCT, oral intake should be stopped, and TPN should be considered (14). Chemical pleurodesis is an alternative if the chylothorax does not respond to thoracentesis and dietary control (15). More recently, patients with postoperative chyle leaks have been treated successfully by lymphangiography and embolization (16, 17). Surgical therapy is recommended when the chest tube drains more than 1.5 L/day, or there is persistent chyle flow for more than 2 weeks, because continuous chest tube drainage is associated with an increased risk of infection, as well as with electrolyte and nutritional losses (18, 19). To treat the chylothorax and Graves’ disease, we initiated conservative therapy with fasting, TPN, MCT supplements, and chest tube drainage and treated the underlying disease with methimazole and propranolol. However, the chylothorax did not decrease after these conservative therapies.

In chylothorax cases associated with goiter other than traumatic chylothorax due to thyroid surgery, therapeutic options include anti-thyroid drugs (3), transcervical thyroidectomy (4), and 131I therapy (13). There is no preferred therapy for chylothorax caused by a retrosternal goiter in Graves’ disease. It may differ from country to country, and it also depends on the patient’s age, goiter size, symptom severity, comorbidities, patient and clinician preferences, medical insurance, medical cost, and availability of 131I therapy.

Some authors have reported for the treatment of chyrothorax due to substernal goiter. Bonnema SJ et al reported the case which was treated by transcervical thyroidectomy (20). In two cases, patients were managed by transcervical thyroidectomy and sternostomy (21, 22). In another case, the patient was treated with 131I but therapeutic effect of radioiodine was unknown because the patient died (13). In the other case, patient was improved by treatment of underlying disease with methimazole, iodine and conservative therapy after 3 month (3).

Our patient was unwilling to undergo surgery. Therefore, we decided to treat the Graves’ disease and goiter with 131I. The chylothorax and goiter size decreased more quickly than expected. Although it is not clear, the rapid decrease in chyle flow due to relief of compression of the thoracic duct may have contributed to the initial clinical improvement in the chylothorax.

In conclusion, this case demonstrated successful treatment of a chylothorax associated with substernal goiter in Graves’ disease using radioactive iodine. Although such cases are very uncommon, physicians should know that chylothorax is a rare complication of a substernal goiter and can be managed using 131I therapy instead of surgery.