1. Context

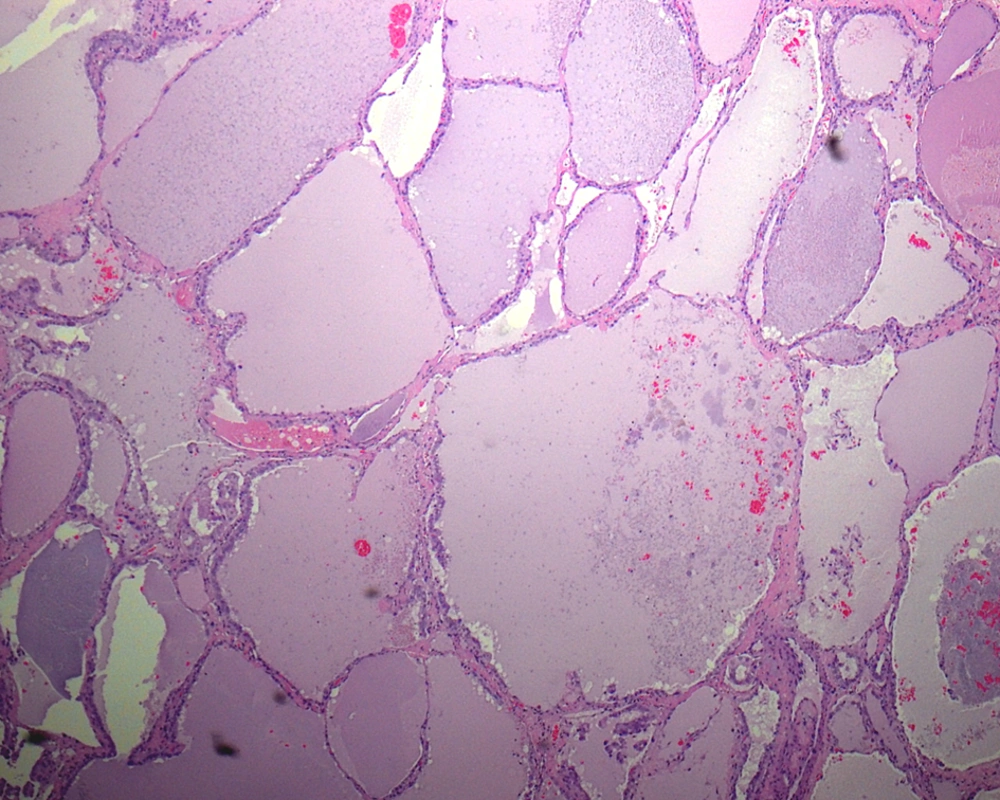

Papillary carcinoma of thyroid (PTC) is the most common malignant thyroid tumor, comprising approximately 80% of all thyroid cancers. PTC has a very broad morphologic spectrum with many histologic variants (Box 1), which their classification is important because patient's outcome in some variants differ from conventional PTC (1). The follicular variant of PTC (FVPTC) is defined by the presence of tumor cells arranged almost entirely in a follicular pattern with the nuclear features identical to that of PTC. The macrofollicular variant of PTC (MFVPTC) is an extremely rare entity, accounting for 0.3% of PTC in Japan (1). It was first described as a distinct entity by Albores-Saavdra et al. in 1991 (2). Histologically, according to the definition given by Albores-Saavdra, MFVPTCs are characterized by the predominance of macrofollicles (follicles >250 μm) (Figure 1), occupying more than 50% of a cross-sectional area (3, 4). In contrary, according to Gamboa-Dominguez et al. (5), the MFVPTC is composed of follicles with a mean diameter of at least 200 μm, surrounded by a thick fibrous capsule that resembles macrofollicular adenoma or nodular goiter.

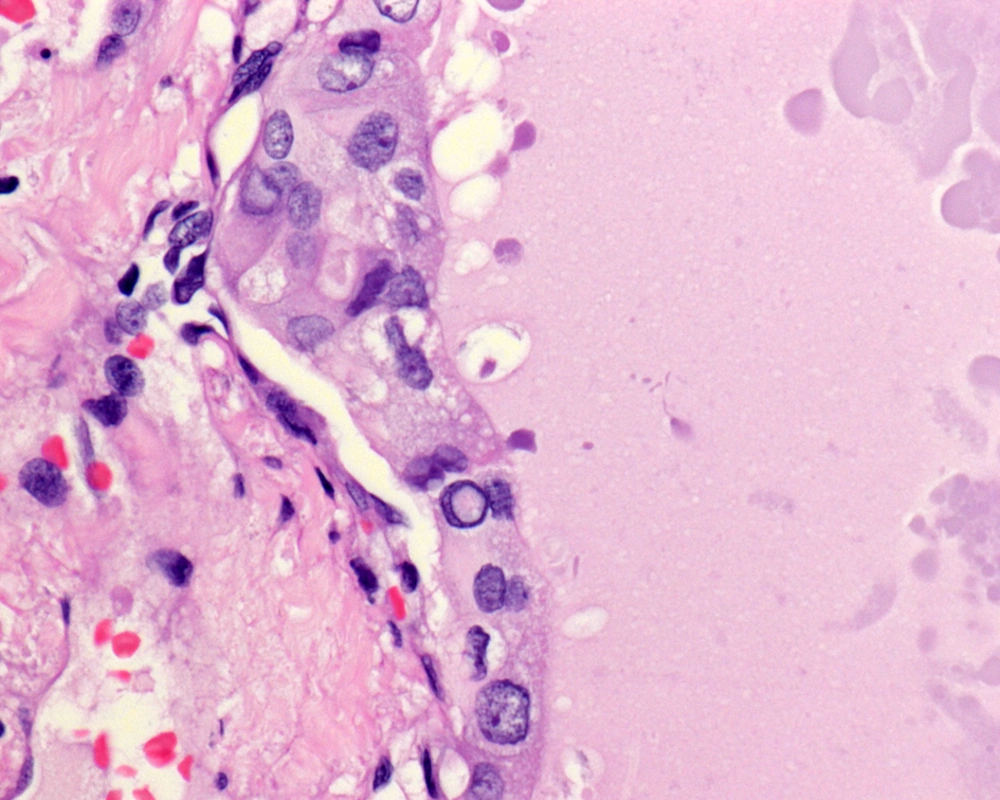

The cells lining the macrofollicles have nuclear features of characteristic PTC including enlarged ground glass clear nuclei, with intranuclear pseudoinclusions and nuclear grooves (Figure 2).

| Variants |

|---|

| Conventional |

| Follicular variant |

| Papillary microcarcinoma |

| Tall cell |

| Oncocytic |

| Columnar cell |

| Diffuse sclerosing |

| Solid |

| Clear cell |

| Cribriform-morular |

| Macrofollicular |

| PTC with prominent hobnail features |

| PTC with fasciitis-like stroma |

| Combined papillary and medullary carcinoma |

| PTC with dedifferentiation to anaplastic carcinoma |

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Clinical Features and Presentation

PTC represents the most common thyroid epithelial malignancy diagnosed in the regions where thyroid goiter is not endemic. Although they are rare before age of 15, they represent the most common pediatric thyroid malignancy. The most common etiologic factor is radiation, but genetic susceptibility and hormonal factors also contribute to the development of PTC. Generally, the median age at diagnosis is 44 years in FVPTC, which is similar to that of PTC (43 years) (5). The female to male ratio is 6:1. Both FVPTC and PTC are presented as thyroid masses. At the time of diagnosis, the rates of extensive extrathyroidal local spread, bilateral lesions, and vascular invasion were higher in FVPTC than in classical PTC (6, 7). It is well known that patient outcomes of some variants differ from conventional PTC (1).

As shown by previous studies from Western countries, MFVPTC is characterized clinically by nonaggressive biologic behavior with a low incidence of lymph node metastases and good prognosis (2, 4). Moreover, it has a macrofollicular pattern. Therefore, it might represents clinically a crucial source of diagnostic error since it can be easily misinterpreted as a benign disease such as goiter, macrofollicular adenoma, Grave’s disease, or hyperplastic adenomatoid nodule (6). In a report of five MFVPTC cases by Fukushima et al. (8), preoperative ultrasonographic examination showed that two patients had benign nodulesand the remaining were suspected of having PTC. None of the patients showed apparent lymph nodes metastases on ultrasonographyor massive extrathyroidal extension before operation although lymph node metastases were observed in three patients on postoperative pathologic examination. It is possible that some macrofollicular variant cases have been followed-up based on a misdiagnosis of benign thyroidnodules.

The prognosis of MFPTC is reported to be excellent with a low incidence of metastasis as compared to conventional PTC or columnar cell variant (9, 10). The various factors which are considered to be of prognostic importance in a patient with well differentiated PTC are young age, small tumor size, absence of extra thyroid extension or blood vessel invasion (11). Recent studies by Liu et al. (12) have showed that encapsulated lesions without invasion have an excellent prognosis. These encapsulated lesions have a clinical behavior very similar to follicular neoplasms of the thyroid (12).

2.2. Morphologic and Immunohistochemical Features

FVPTC in general and MFVPTC in particularpose common and challenging diagnostic difficulties. The difficulties are encountered in both cytologic preparations and histologic sections and are usually due to a high number of these tumors develop within a background of nodular goiter or macrofollicular adenoma.

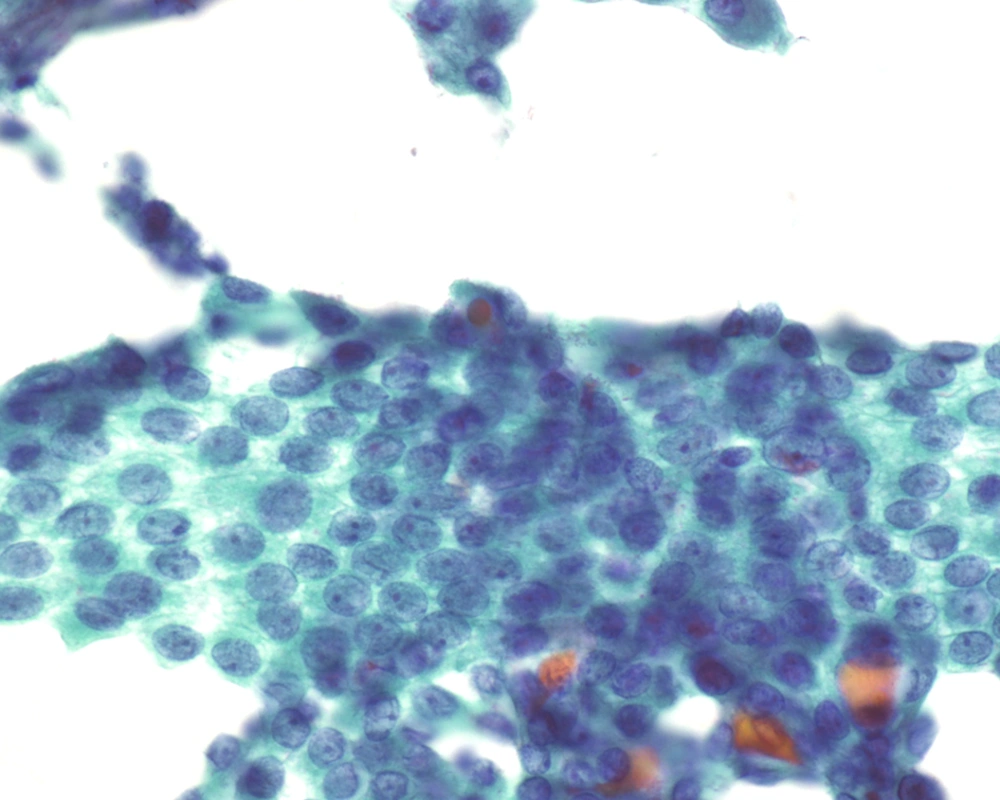

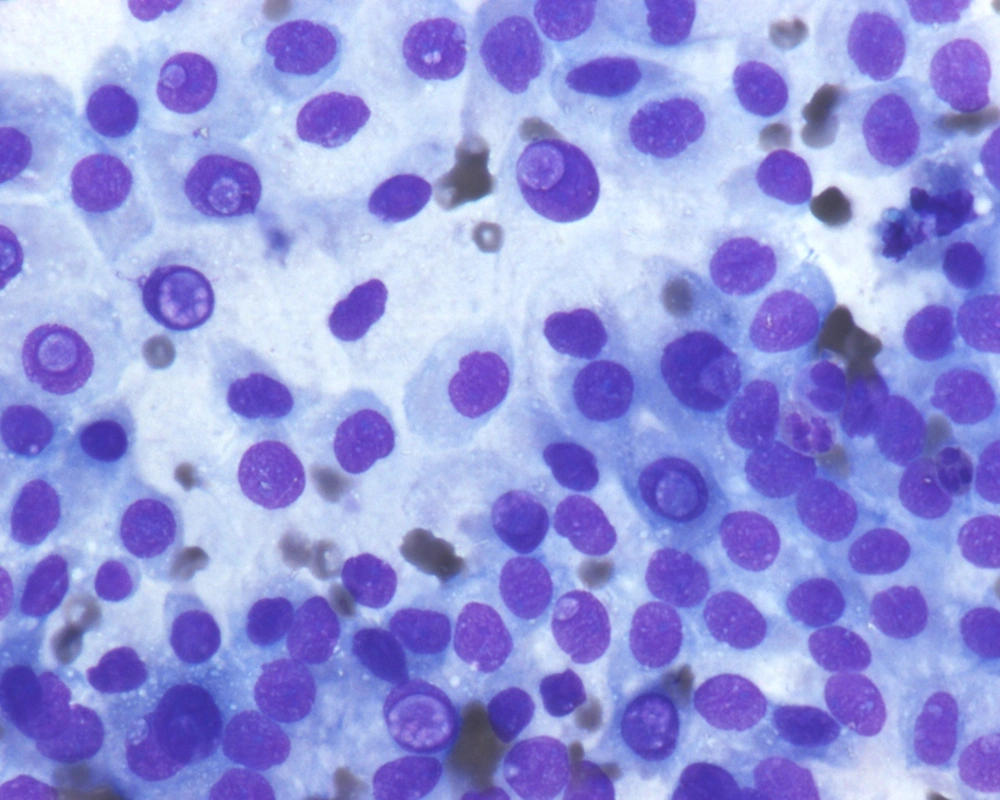

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) is an efficient tool in evaluation of many superficial organs such as lymph nodes (13) as well as deep organs such as the pancreas (14). In contrast to FNA findings of the classical PTC, where this investigation has been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity allowing endocrine surgeons to proceed with total thyroidectomy (15-19), FNA of FVPTC, especially the MFVPTC, is not much helpful in reaching this diagnosis. The macrofollicles contains abundant colloid and some are lined by follicular type of epithelium; hence, the cytologic features are quiet often similar to adenomatous goiter and to macrofollicular adenoma (20-24). For discriminating MFVPTC from these entities on FNA cytology, we depend on the nuclear features characteristic for PTC, which are typically seen in MFPTC (25).The cellular features of MFVPTC are identical to that of PTC and include clear nuclei, nuclear grooves, and intranuclear pseudoinclusions (26) (Figures 3 and 4). MFVPTC tends to have fewer calcifications and less psammoma body formation in comparison to conventional PTC. In all FVPTCs, including the macrofollicular variant, a significant inter-observer and intra-observer variations have been noted even among experts, with major inter-observer disagreements reported in up to 40% of cases (27). A general consensus exists as to the most important diagnostic features, which include nuclear clearing, nuclear grooves, nuclear overlapping and crowding, nuclear membrane irregularity, and nuclear enlargement. Discrepancies arise due to the lack of agreement on the minimal necessary criteria for a definite diagnosis of MFVPTC. Factors that most likely contributed to a false negative diagnosis in some cases included low cellularity, predominance of macrofollicular pattern, presence of macrophages, paucity or absence of nuclear pseudoinclusions and/or nuclear grooves, and presence of moderate to abundant thin watery colloid. Sampling was probably one of the causes for the false negative diagnosis since the nuclear changes suggestive of papillary carcinoma, while undoubtedly present in the histologic sections, were often focal in nature. Unfortunately, the presence of few grooves is not particularly helpful in making the correct diagnosis as it can be focally seen in a variety of lesions including goiter and Hurthle cell lesions. Nuclear overlap, small peripheral nucleoli in atypical follicular cells with grooves, and presence of focal abnormal dense colloid in a background of watery and thin colloid were the most common features in the FNA of MFPTC (26, 28).

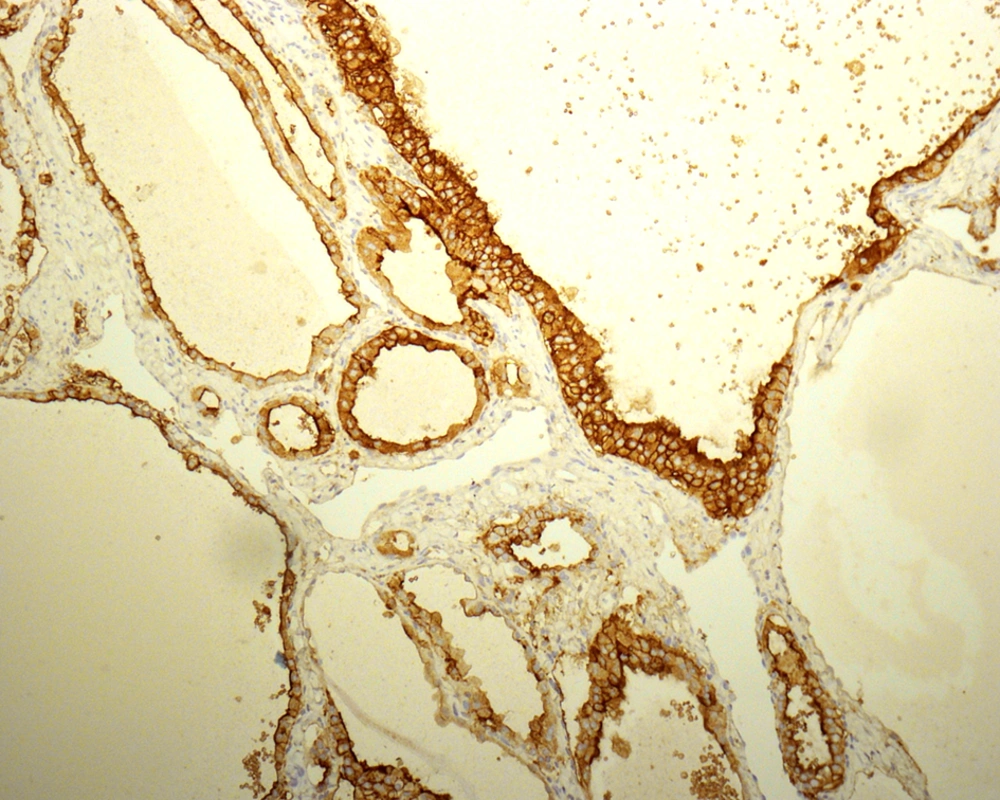

The absence of strict and uniform criteria among expert pathologists, particularly in difficult cases, results in the use of terms such as “multifocal PTC arising in a benign nodule” and “follicular tumor of uncertain malignant potential”. Therefore, there is controversy regarding reporting the cytohistologic condition of these lesions (27, 29-31) and a range of proposals have been made to clarify this issue. LiVolsi and Baloch preferred a scheme in which a diagnosis of MFVPTC would be made on any encapsulated lesion showing any area with the characteristic cytologic features of PTC (32). Chan suggested using stricter criteria including the evaluation of major and minor features. Some immunohistochemical markers, such as high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, cytokeratin 19, vimentin, HBME1 (Figure 5), CD57, CD15, and CD44 have been reported to be more commonly expressed in PTCs than in benign thyroid lesions. These markers are not sufficiently discriminatory to aid in the diagnosis of problematic encapsulated follicular lesions of the thyroid (31).

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Genetics of FVPTC/MFVPTC and Its Diagnostic Clinical Utility

Several oncogenes are involved in tumor genesis of thyroid carcinoma (33, 34). MFVPTC has molecular characteristics between the two well-differentiated thyroid carcinomas, i.e. follicular carcinoma (FC) and PTC. FC is characterized by RAS mutations and PAX8/PPARγ rearrangement (34-37). The gene fusion of PAX8/PPARγ rearrangement has been cytogenetically defined as translocation t(2:3) (q13; p25) (36). PTC has a genetic profile consisting of somatic rearrangements of the RET proto-oncogene (34, 38) and BRAF mutations (39, 40). MFVPTC has a high occurrence of RAS mutations and PAX8/PPARγ rearrangements (41) but a less common BRAF K601E form, which is present in about 7% of cases (40). Other reported BRAF mutations in MFVPTC include V600E, G474R, and a novel gain of function T5991-VKSR (600-603) deletion (42, 43). These mutations with the exception of G474R share biologic similarities in activating the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. The G474R mutation knocks down the enzymatic activity of BRAF, providing a first example of a knockdown mutation in MFVPTC. The genetic profiling of thyroid tumors offers potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets in their management.

Currently, by the clinical utility of molecular testing in MFVPTC, up to 3.6% of specimen will fall into the indeterminate category when using the Bethesda classification for the diagnosis of thyroid neoplasms. The risk of malignancy in this category might be up to 15% to 30%. Forty molecular tests, especially assays for BRAF V600E and Kras mutations, have been shown to play an adjunct role in diagnosis of cytology samples in equivocal cases classified as follicular lesions of undetermined significance, improving diagnostic accuracy of malignancy and directing subsequent therapy (44, 45). Their utility, nevertheless, is restricted to classical PTCs due to the low incidence of BRAF mutations in MFVPTC and the high occurrence of Kras mutations in benign follicular lesions (42). Other experts argue that the RET/PTC gene translocation, a hallmark of PTC, fails to provide the definite support for the diagnosis, because it is found in only approximately one-third of all cases of PTCs and some studies have found this gene translocation even in benign thyroid lesions (46, 47).

4. Conclusions

MFVPTC is a rare variant of PTC and shows a good prognosis. It can be extremely difficult to diagnose on preoperative clinical and cytologic examinations; however, if accurate diagnosis could be feasible in the future, limited surgical excision would be considered. The description of this variant is important from all clinicopathologic aspects as it highlights the potential pitfall in considering a macrofollicular-patterned lesion as benign. Recognition of such diverse tumor entities will allow accurate pathologic diagnosis and most optimal clinical management.