1. Background

Overweight and obesity are highly prevalent among children and adolescents worldwide (1). The findings of a survey on school-aged children from 30 provinces of Iran indicated that 21.6% of these children were overweight and obese (2). With regard to several physical and psycho-social complications, childhood obesity seems to be associated with hypertension, type II diabetes, dyslipidemia, asthma, depression, low self-esteem, negative body image, and social marginalization in children and adolescents (3-7). Moreover, childhood obesity increases the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and obesity in adulthood (8, 9). Hence, weight management in childhood can serve as a primary preventive measure to fight against obesity and CHD in adulthood.

While lifestyle modification is considered to be the cornerstone of obesity prevention and treatment in the early years of life, there are some inconsistencies regarding the efficiency of existing behavioral interventions (10, 11). Kamath et al. claimed that lifestyle interventions aimed at preventing pediatric obesity caused only small changes in targeted behaviors and no significant change in BMI, compared to the control groups (10). Moreover, the previous studies revealed that office-based obesity treatments have not been effective in achieving behavioral modifications (12) since many patients did not adhere to diet and exercise prescriptions (13). The findings of a recent meta-analysis consisting of 26 trials indicated the effectiveness of educational interventions in treatment; however, they were not effective in the prevention of childhood obesity (11). To combat obesity as a multi-factorial health problem, evidence indicate that healthy lifestyle may happen as a result of changes in factors mediating the obesity-related behaviors (i.e., diet and physical activity) (8, 14). Furthermore, the literature also introduces a wide range of personal and environmental factors influencing children and adolescents’ lifestyle and consequently their weight status (15-19); which need to be considered in order to motivate adolescents to modify their lifestyle and have weight management based on the healthy behavioral recommendations.

The findings of a meta-analysis demonstrated the longer-term beneficial effects of family-based behavioral interventions aimed at modifying adolescents’ beliefs and actions regarding obesity-related behaviors (ORB), in comparison to both self-help programs and standard dietary counseling (20). Previous studies also revealed that motivation-based interventions had beneficial effects on improving multiple health behaviors, and its potential benefits on weight-related behaviors were documented (21, 22). Accordingly, several studies have focused on motivation and its underlying cognitive and emotional factors, including self-determination, self-efficacy, and body image, and the findings provide a promising mechanism to help the overweight adolescents to choose and maintain healthy lifestyles (13, 23-27).

Most interventions conducted in Iran on adolescents have mainly focused on physical activity or dietary behaviors (5, 28-30). Based on previous qualitative studies on Iranian adolescents, self-confidence and acceptability, as well as perceived priority of studying, perceived ability to control weight, and the perceived health-threatening consequences of excessive weight gain were the main personal factors influencing the adolescents’ motivation to modify unhealthy lifestyles and have weight management (17, 19). Accordingly, one can hypothesize that a motivation-based educational program, focusing on improvement and modification of the abovementioned influential beliefs and perceptions, can be effective in changing the adolescent’s lifestyle and controlling weight.

2. Objectives

Considering the limited number of similar studies in Iran, this study aimed to assess the effectiveness of a motivation-based educational program in comparison to the conventional dietary counseling in modifying lifestyle and controlling weight in overweight and obese adolescents in Tehran.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Randomization

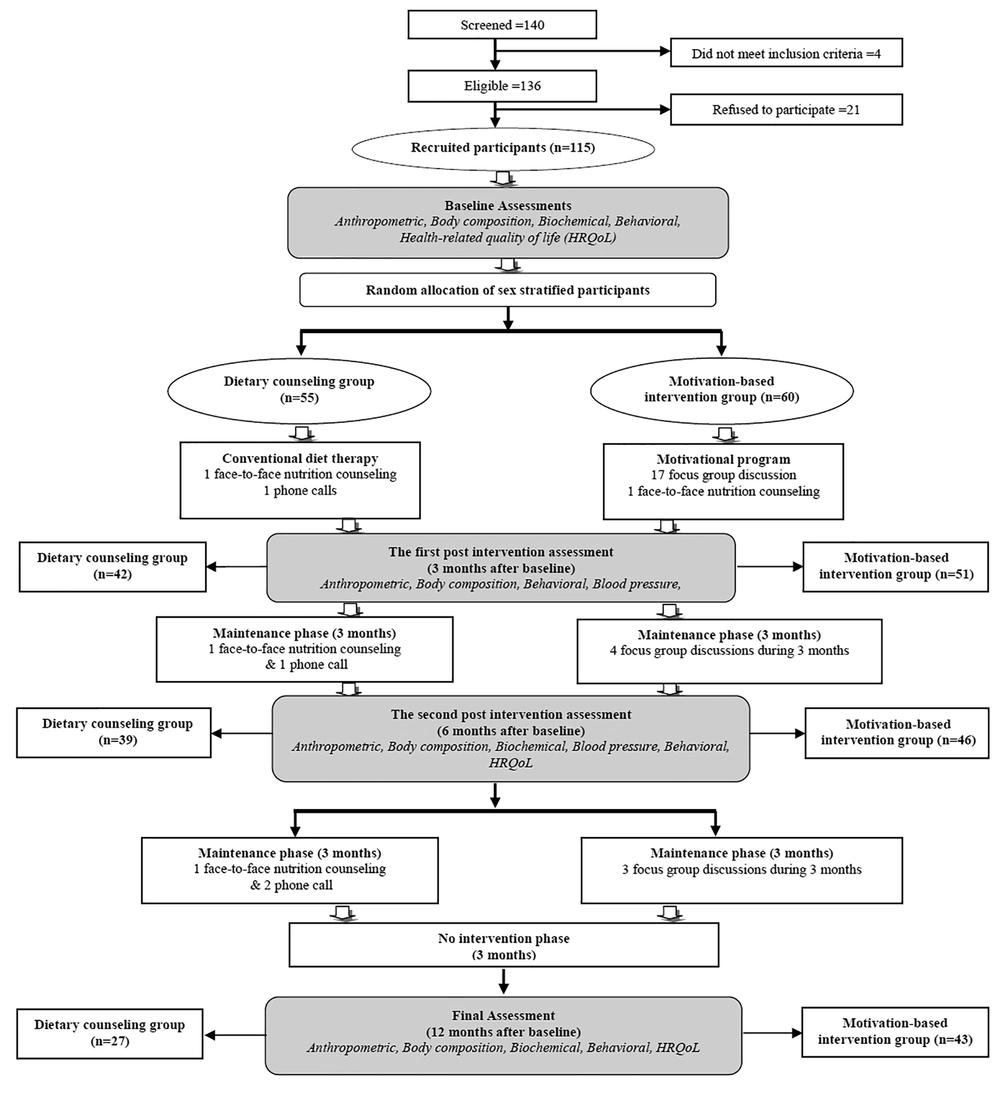

This study was conducted in Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS) framework (31). Using World Health Organization (WHO) cut-off point (32), 140 overweight or obese adolescents aged 13 - 17 years, who had participated in the TLGS during 2008 - 2010, were screened. The sampling framework of the current study is illustrated in Figure 1.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Iranian registry of clinical trials (IRCT201012234540N1). Following the approval of the research ethics committee of the RIES, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (No. EC 347), the study was carried out. All the participants signed the informed consent forms and completed preliminary assessments at the health care unit. Random allocation was conducted using randomized number table. All adolescents and parents were provided with a detailed outline of the research, including a review of either the motivation-based educational program or the dietary counseling program and the assessment procedures based on the group they were allocated to. All parents of adolescents in the motivation-based educational program participated in an extra session held to give them some information about the program and modification of obesity-related behaviors.

3.2. Motivation-based Educational Program

Based on a preliminary conceptual framework (17), socio-environmental factors resulted in the formation of a series of predisposing beliefs, leading to motivation loss for a healthy lifestyle and consequently excessive weight gain in adolescents living in Tehran. The predisposing beliefs consisted of the perceived priority of educational achievements, perceived lack of threat, perceived acceptability, and perceived inability.

The lessons scheduled for the intervention group were developed based on the manual of weight management in adolescents (33). The intervention program encompassed intensive and maintenance phases. Table 1 briefly outlines the content of each educational session. The intensive phase consisted of 17 focus-group discussions as well as a face-to-face nutritional counseling session at the end of program. To modify their ORB, the adolescents also received a workbook containing some information about their weight status, common beliefs among obese adolescents that could influence their motivation to choose healthy life style and have weight management, and the necessary behavioral skills (managing stress and time and determining suitable daily physical activity and dietary intakes). The maintenance programs encompassed four focus group discussions over a six-month period. During the maintenance phase, an expert used motivational interviewing techniques to encourage participants to identify their own challenges and options to overcome the obstacles (Figure 1). Furthermore, a parental session was held to give the parents an overview of the whole program.

| Topics | Content |

|---|---|

| Introduction and readiness assessment (1 session) | Information on the educational program, strategies, aims, and outcome goals; self-assessment of weight status and readiness based on motivational interviewing; recognizing thoughts and perceptions related to ORB in adolescents (perceived threat, perceived acceptability, perceived priority and perceived ability) |

| Stress management (8 sessions) | Definition of stress and common stressors; effect of stress management on weight control; identification of different reactions to stressors; Identification of effective coping strategies and statements to deal with stressful situations; practice: relaxation methods, positive self-talk, problem solving, decision making and time management |

| Physical activity (5 sessions) | Introduction to physical activity guidelines for adolescents; examples of different levels of activities; self-assessment of current physical activity levels and identification of age-appropriate physical activity; strategies for being active, reducing sedentary time to increase daily physical activity and tackle common barriers to exercise |

| Nutrition (4 sessions) | Introduction to healthy eating and its components; introduction to the food guide pyramid and recommended portion sizes for adolescents; self-assessment of eating and energy intake; planning a healthy diet considering energy intake and servings of food groups |

| Maintaining change (7 sessions) | Discussing of change goals; identifying strengths and weaknesses of program; planning ahead to manage weaknesses and goal setting |

3.3. Dietary Counseling Program

This group had three face-to-face conventional dietary counseling sessions followed up by phone calls. The first dietary counseling session was held at the beginning of the study and followed by two further sessions every three months. Each session began with the assessment of the adolescent’s current diet and continued with some recommendations regarding an appropriate diet. Using phone calls, a trained nutritionist probed for any challenges the adolescents encountered during diet therapy.

3.4. Assessments

Height and waist and wrist circumferences were measured according to the TLGS protocol (31). Weight and body composition were assessed by using a portable bioelectrical impedance analyzer (BIA) (Model, GAIA 359 Plus, Co. Cosmed, Italy). The participants’ blood samples were collected after a 12 - 14 hours overnight fasting, while they were in a sitting position. All biochemical assessments and blood pressure measurements were conducted based on a standard protocol (34). To assess HRQOL, we used the validated Iranian version of the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scales, a 23-item self-administered questionnaire addressing child self-reports and parent proxy-reports in four subscales (35).

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Considering the power of 80% and the 2-tailed α of 0.05, the required sample size was estimated to be 54 per group. Assuming 10% losses to follow-up, the final sample size was estimated to be 59 per group. Statistical analysis was performed using intention to treat principals. Before the main analysis, the normality of continuous variables was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test. The data are described as the Mean ± SD or median (range), where applicable. The mean difference of baseline continuous variables between the groups were compared using the student t-test or Mann-Whitney U. Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square test.

To determine the effects of the treatments on the dependent variables over time, the data were analyzed using random effects mixed modeling and the generalized estimating equations model (GEE), when applicable. We also compared the treatment groups during the follow-up period. Missing values were then imputed (multiple imputation) before applying the mixed model procedure with the participants treated as random effects. The data analysis was performed using Stata Corp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP. The statistical significance was set at < 0.05.

4. Results

The mean age and BMI Z-score were 14.5 ± 1.2 and 2.42 ± 0.62, respectively. In this study, 46% of the participants were male. Of 140 individuals being screened for participation, four individuals did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 21 individuals refused to participate as such 115 individuals participated to have the baseline assessment and were then assigned into the dietary counseling (n = 55) and the motivation-based program (n = 60). In both motivation-based and conventional dietary counseling groups, response rates decreased, compared to the baseline assessment at each follow-up (1st follow-up: 85.0 and. 76.4%; 2nd follow-up: 76.7 and. 71.0%; 3rd follow-up: 71.7 and. 49.1%). The rates, however, further decreased in the conventional dietary counseling group, compared to the motivation-based program.

Table 2 compares the anthropometric, body composition, cardio-metabolic indices, and health-related quality of life scores in each group at the baseline assessment. As it can be observed, the motivation-based program and dietary counseling groups were statistically different in terms of BMI Z-scores and HRQOL school functioning score at baseline. In order to avoid the potential interfering effects, all the analyses were conducted after adjusting the baseline values. The results of mixed model are presented in Tables 3 and 4. P values showed the between groups comparison at each follow-up.

| Motivation-based Program (N = 60) | Dietary Counseling (N = 55) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, No. (%) | 29 (48.3) | 24 (44.9) | 0.68 |

| BMI Z-score | 2.30 ± 0.59 | 2.56 ± 0.64 | 0.03 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 97.0 ± 11.2 | 98.8 ± 11.5 | 0.40 |

| Wrist circumference (cm) | 17.1 ± 1.3 | 17.0 ± 1.2 | 0.67 |

| PBF (%) | 32.8 ± 4.9 | 34.4 ± 6.0 | 0.13 |

| MBF (kg) | 26.7 ± 7.4 | 29.0 ± 9.6 | 0.15 |

| LBM (kg) | 54.0 ± 10.1 | 53.5 ± 8.6 | 0.81 |

| TBW (kg) | 38.9 ± 7.2 | 38.5 ± 6.2 | 0.81 |

| SLM (kg) | 49.4 ± 9.2 | 48.9 ± 7.8 | 0.74 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 111 ± 15.9 | 110 ± 15.5 | 0.61 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 72.3 ± 9.4 | 73.3 ± 9.6 | 0.56 |

| FBS (mg/dL) | 89.8 ± 7.3 | 89.9 ± 8.7 | 0.26 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 137 ± 58.5 | 142 ± 67.7 | 0.65 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 155 ± 32.9 | 159 ± 26.8 | 0.08 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 43.9 ± 9.1 | 44.4 ± 10.0 | 0.47 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 83.8 ± 25.0 | 86.2 ± 22.0 | 0.21 |

| Insulin (µU/mL) | 21.8 ± 10.9 | 20.8 ± 10.8 | 0.85 |

| Total DEE (kj/kg/d) | 122 ± 58.5 | 119 ± 51.0 | 0.79 |

| Energy intake (kj/kg/d) | 119 ± 35.6 | 115 ± 39.0 | |

| Physical functioning | 79.8 ± 14.5 | 83.1 ± 14.7 | 0.23 |

| Emotional functioning | 80.0 (60.0 - 88.8) | 80.0 (65.0 - 90.0) | 0.40 |

| Social functioning | 87.5 (70.0 - 98.8) | 90.0 (80.0 - 100.0) | 0.11 |

| School functioning | 77.5 (65.0 - 90.0) | 90.0 (70.0 - 95.0) | 0.02 |

| HRQOL total | 78.1 ± 13.2 | 82.0 ± 14.2 | 0.13 |

| P-Physical functioning | 75.0 (59.4 - 90.6) | 65.6 (53.1 - 87.5) | 0.17 |

| P-Emotional functioning | 65.0 (55.0 - 80.0) | 60.0 (45.0 - 80.0) | 0.19 |

| P-Social functioning | 75.0 (55.0 - 90.0) | 75.0 (55.0 - 100.0) | 0.91 |

| P-School functioning | 75.0 (60.0 - 85.0) | 75.0 (55.0 - 90.0) | 0.76 |

| P-HRQOL total | 72.3 (62.2 - 83.1) | 66.9 (54.1 - 83.3) | 0.35 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DEE, daily energy expenditure; FBS, fasting blood sugar; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein-cholesterol; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; LBM, lean body mass; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein-cholesterol, MBF, mass of body fat; PBF, percent body fat; P-Emotional functioning, parent proxy-reported emotional functioning; P-HRQOL total, parent proxy reported HRQOL total; P-Physical functioning, parent proxy-reported physical functioning; P-School functioning, parent proxy-reported school functioning; P-Social functioning, parent proxy-reported social functioning; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SLM, soft lean mass; TBW, total body water; TG, triglycerides

aData are presented as mean ± SD or median (Q1 - Q3) unless otherwise indicated.

| Follow Up 1 | P Value | Follow Up 2 | P Value | Follow Up 3 | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation- based Program | Dietary Counseling | Motivation-based Program | Dietary Counseling | Motivation-based Program | Dietary Counseling | ||||

| BMI Z-score | 2.35 ± 0.59 | 2.47 ± 0.67 | 0.86 | 2.10 ± 0.68 | 2.40 ± 0.73 | 0.29 | 2.06 ± 0.70 | 2.48 ± 0.67 | 0.44 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 97.0 ± 10.9 | 97.3 ± 9.47 | 0.75 | 90.9 ± 13.1 | 92.8 ± 14.3 | 0.19 | 91.5 ± 13.3 | 94.3 ± 10.0 | 0.40 |

| Wrist circumference (cm) | 16.9 ± 1.46 | 17.0 ± 1.22 | < 0.01 | 16.5 ± 1.45 | 16.7 ± 1.19 | < 0.01 | 16.5 ± 1.42 | 16.7 ± 1.21 | < 0.05 |

| PBF (%) | 33.5 ± 5.19 | 34.5 ± 5.56 | 0.51 | 31.6 ± 5.74 | 33.5 ± 5.82 | 0.18 | 32.0 ± 6.13 | 33.8 ± 6.26 | 0.18 |

| MBF (kg) | 27.6 ± 7.65 | 29.0 ± 9.39 | 0.56 | 25.7 ± 8.11 | 28.4 ± 9.85 | 0.97 | 26.5 ± 8.83 | 29.4 ± 9.28 | < 0.05 |

| LBM (kg) | 54.0 ± 9.88 | 53.3 ± 8.57 | 0.93 | 54.8 ± 10.2 | 54.4 ± 9.07 | 0.36 | 55.2 ± 10.2 | 56.1 ± 8.33 | 0.13 |

| TBW (kg) | 38.9 ± 7.12 | 38.4 ± 6.16 | 0.86 | 39.4 ± 7.34 | 39.1 ± 6.53 | 0.39 | 39.7 ± 7.37 | 40.4 ± 5.99 | 0.08 |

| SLM (kg) | 49.4 ± 9.08 | 48.6 ± 7.74 | 0.81 | 50.2 ± 9.37 | 49.7 ± 8.20 | 0.25 | 50.5 ± 9.41 | 51.3 ± 7.62 | < 0.05 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 112 ± 15.3 | 108 ± 16.9 | 0.30 | 107 ± 9.56 | 103 ± 10.7 | 0.40 | 109 ± 11.3 | 110 ± 7.19 | 0.98 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 72.5 ± 7.83 | 73.2 ± 8.73 | 0.53 | 72.0 ± 7.39 | 69.4 ± 6.56 | 0.07 | 69.5 ± 6.48 | 71.8 ± 8.67 | 0.12 |

| FBS (mg/dL) | - | - | - | 92.5 ± 5.14 | 97.5 ± 6.99 | < 0.001 | 92.7 ± 7.01 | 92.0 ± 5.62 | 0.88 |

| TG (mg/dL) | - | - | - | 137 ± 64.8 | 109 ± 50.7 | < 0.01 | 124 ± 53.1 | 132 ± 60.0 | 0.39 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | - | - | - | 160 ± 31.9 | 160 ± 26.5 | 0.78 | 162 ± 32.5 | 158 ± 26.3 | 0.38 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | - | - | - | 43.4 ± 9.58 | 42.5 ± 9.20 | 0.26 | 41.4 ± 9.99 | 44.2 ± 9.77 | 0.72 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | - | - | - | 89.4 ± 26.7 | 96.1 ± 24.0 | 0.23 | 95.8 ± 27.5 | 87.4 ± 23.3 | 0.10 |

| Insulin (µU/mL) | - | - | - | 17.9 ± 7.86 | 17.6 ± 8.14 | 0.94 | 17.9 ± 8.25 | 17.6 ± 8.32 | 0.94 |

| Total DEE (kj/kg/d) | 107 ± 34.7 | 127 ± 50.8 | 0.04 | 126 ± 75.2 | 125 ± 77.9 | 0.96 | 118 ± 29.2 | 123 ± 29.9 | 0.56 |

| Energy intake (kj/kg/d) | 86.3 ± 37.5 | 79.5 ± 43.6 | 0.33 | 78.5 ± 25.0 | 79.1 ± 20.0 | 0.67 | 92.6 ± 31.1 | 83.1 ± 26.3 | 0.14 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DEE, and daily energy expenditure; FBS, fasting blood sugar; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LBM, lean body mass; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein-cholesterol; MBF, mass of body fat; PBF, percent body fat; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SLM, soft lean mass; TBW, total body water; TG, triglycerides.

aData are presented as Mean ± SD.

| Follow Up 1 | P Value | Follow Up 2 | P Value | Follow Up 3 | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation-based Program | Dietary Counseling | Motivation-based Program | Dietary Counseling | Motivation-based Program | Dietary Counseling | ||||

| Physical functioning | 80.6 ± 15.7 | 81.6 ± 16.4 | 0.60 | 81.7 ± 14.0 | 82.5 ± 14.1 | 0.75 | 83.4 ± 14.9 | 84.4 ± 15.5 | 0.87 |

| Emotional functioning | 80.0 (60.0 - 90.0) | 80.0 (55.0 - 85.0) | 0.53 | 75.0 (58.8 - 90.0) | 80.0 (60.0 - 95.0) | 0.94 | 80.0 (55.0 - 90.0) | 85.0 (63.8 - 95.0) | 0.30 |

| Social functioning | 90.0 (70.0 - 95.0) | 90.0 (80.0 - 95.0) | 0.75 | 85.0 (70.0 - 100) | 90.0 (80.0 - 100) | 0.75 | 90.0 (75.0 - 95.0) | 95.0 (73.8 - 100) | 0.83 |

| School functioning | 75.0 (70.0 - 90.0) | 85.0 (73.8 - 90.0) | 0.33 | 80.0 (70.0 - 95.0) | 85.0 (65.0 - 95.0) | 0.44 | 80.0 (70.0 - 95.0) | 87.5 (65.0 - 91.3) | 0.22 |

| HRQOL total | 79.4 ± 13.2 | 80.2 ± 13.0 | 0.52 | 79.0 ± 14.2 | 81.1 ± 14.3 | 0.70 | 81.1 ± 13.3 | 82.6 ± 15.6 | 0.53 |

| P-Physical functioning | 100 (81.3 - 100) | 85.9 (68.8 - 100) | 0.10 | 90.6 (78.1 - 100) | 78.1 (67.2 - 92.2) | 0.99 | 87.5 (75.0 - 100) | 90.6 (56.3 - 100) | 0.30 |

| P-Emotional functioning | 90.0 (75.0 - 100) | 77.5 (63.8 - 100) | < 0.001 | 70.0 (58.8 - 81.3) | 70.0 (57.5 - 85.0) | 0.70 | 75.0 (65.0 - 80.0) | 67.5 (58.8 - 80.0) | 0.72 |

| P-Social functioning | 100 (85.0 - 100) | 90.0 (75.0 - 100) | 0.05 | 90.0 (75.0 - 100) | 80.0 (58.8 - 95.0) | 0.97 | 90.0 (85.0 - 100) | 90.0 (58.8 - 100) | 0.97 |

| P-School functioning | 90.0 (80.0 - 100) | 90.0 (68.7 - 100) | < 0.01 | 90.0 (73.8 - 100) | 75.0 (60.0 - 87.5) | 0.98 | 80.0 (65.0 - 95.0) | 80.0 (60.0 - 91.3) | 0.98 |

| P-HRQOL total | 93.8 (81.7 - 100) | 85.8 (68.4 - 95.0) | 0.001 | 81.4 (71.9 - 91.3) | 76.6 (61.1 - 86.2) | 0.86 | 82.2 (72.5 - 89.4) | 75.8 (61.7 - 91.3) | 0.28 |

Abbreviations: HRQOL, health-related quality of life; P-Emotional functioning, parent proxy-reported emotional functioning; P-HRQOL total, parent proxy reported HRQOL total; P-Physical functioning, parent proxy-reported physical functioning; P-School functioning, parent proxy-reported school functioning; P-Social functioning, parent proxy-reported social functioning

The comparisons of anthropometric, body composition, cardio metabolic indices, energy intake, and daily energy expenditure (DEE) between motivation-based program and dietary counseling groups are presented in Table 3. The Mean ± BMI Z-scores in months three, six, and 12 in the motivation-based program and the dietary counseling group were 2.35 ± 0.59 vs. 2.47 ± 0.67, 2.10 ± 0.68 vs. 2.40 ± 0.73, and 2.06 ± 0.70 vs. 2.48 ± 0.67, respectively. Regarding the anthropometric indices, there was only a significant difference in wrist circumference between the motivation-based program and the dietary counseling group after three, six and 12 months (16.94 ± 1.46 vs. 17.00 ± 1.22, 16.49 ± 1.45 vs. 16.65 ± 1.19, and 16.50 ± 1.42 vs. 16.67 ± 1.21 respectively; P < 0.05). Moreover, there were significant differences between the motivation-based program and the dietary counseling groups in terms of mass of body fat (MBF) and soft lean mass (SLM) in the last follow-up, with lower values in motivation-based program compared to dietary counseling group for both MBF (26.46 ± 8.83 vs. 29.38 ± 9.28; P < 0.05) and SLM (50.54 ± 9.41 vs. 51.29 ± 7.62; P < 0.05). Regarding the measured cardio-metabolic indices, after adjusting the baseline values, only FBS and TG differed significantly between motivation-based program and dietary counseling groups after a 6-months follow-up, with higher FBS values (97.47 ± 6.99 vs. 92.45 ± 5.14; P < 0.001) and lower TG values in dietary counseling (109.50 ± 50.73 vs. 136.74 ± 64.79; P < 0.01). Compared to the conventional dietary counseling, DEE was lower in motivation-based program in the first follow-up (107 ± 34.7 vs. 127 ± 50.8; P < 0.05).

Table 4 compares self- and proxy-reported HRQOL scores between the motivation-based program and dietary counseling groups for each follow-up. As shown in Table 4, none of the self-reported HRQOL scores for the adolescents significantly differed between the two groups in the three follow-ups. However, except for physical functioning subscale score, all proxy reported HRQOL scores were significantly higher in the motivation-based program, compared to dietary counseling group after a three-month follow-up (P < 0.05).

Considering the P value trend, both the motivation-based program and the dietary counseling groups achieved significant improvements in BMI Z-score, wrist and waist circumferences, MBF, lean body mass (LBM), and SLM after a one-year follow-up (P < 0.001). In this regard, there was, however, a significant difference between the dietary counseling and motivation-based program groups in terms of wrist circumference after a one-year follow-up (P < 0.001). Regarding the measured cardio-metabolic indices, only FBS level increased significantly in both groups after a one-year follow-up (P < 0.001); however, as indicated in Table 2, after adjusting the baseline values, the increase was significantly smaller in the motivation-based program group, compared to the dietary counseling one after a six-month follow-up. In terms of HRQOL scores, the total and subscale scores of HRQOL reported by both adolescents and parents indicated significant changes over time (P < 0.01). During a one-year follow-up, there were no significant difference between the study groups in terms of self-reported HRQOL scores; however, according to parents’ reports, there were significant differences in the emotional functioning subscale and HRQOL total scores between the study groups (P < 0.05), indicating more improvements in the motivation-based program group, compared to the dietary counseling one.

5. Discussion

In this study, time trend analysis showed that both motivation-based educational program and conventional dietary counseling improved BMI Z-score, wrist and waist circumferences. In this regard, wrist circumference was reduced more significantly in the motivation-based educational program group, compared to dietary counseling group. It has been suggested that wrist circumference in overweight/obese adolescents can serve as an insulin resistance marker (36); hence, a motivation-based educational program might be more effective in preventing insulin resistance and its relevant risks, compared to conventional dietary counseling.

In the current study, time trend analysis revealed no significant improvement in cardio metabolic indices for the study groups; however, the other studies have documented significant improvements in cardio metabolic risk factors after modest reduction in BMI Z-score following the interventions (28-30). Although our study failed to find out the beneficial effects of weight reduction on cardio metabolic indices, our findings are still promising. While time trend analysis indicated significant increase in FBS for the both study groups, FBS level were still within the normal range, and the increase was smaller in the motivation-based group, indicating a favorable effect of the intervention program, compared to conventional diet counseling. In line with the present findings, another study on Iranian adolescents reported similar findings regarding cardio-metabolic risk factors; FBS increases in the fourth phase compared to the first phase of their study (5).

In the current study, time trend analysis suggested that both motivation-based program and conventional dietary counseling improved both children’s self-reported and parent’s proxy-reported HRQOL scores; however, according to the parents, there was a significantly greater improvement in the motivation-based group compared to the dietary counseling in short-term. Based on a systematic review, overweight and obese children and adolescents reported lower HRQOL scores, compared to their normal weight counterparts, and the HRQOL score was inversely related to BMI (37). In agreement with the findings of Tsiros’ et al. (37) study, a study conducted on adolescents in Tehran reached similar findings (3). Since, both motivation-based program and conventional dietary counseling indicated a decrease in the BMI Z-score in the current study, the reduction seems to contribute to the improvements in HRQOL scores in both groups. Our findings are in line with those of the previous studies revealing improvements in HRQOL after participation in weight loss programs (4, 5). However, HRQOL improvement might be due to changes occurring in mediators or behavioral factors, and this needs further investigation in future studies.

To mention the strengths of our study, to the best knowledge of the researcher, this is one of the first attempts to compare the effects of conventional dietary counseling routinely performed by nutritionists or general practitioners in Iran with those of a motivation-based educational program on the adolescents in Tehran. Regarding the limitations of the study, the limited sample size did not allow the comparison of the groups in terms of gender. Moreover, there was a considerable dropout rate in the sixth and 12th months; however, there were no significant difference in the main study variables at baseline between adolescents with and without a complete follow-up measurements. Furthermore, due to some cultural barriers, we could not assess the stage of puberty in the study participants. Finally, these findings are limited to a sample of urban adolescents and cannot be generalized to rural populations.

In conclusion, the motivation-based program, which encompassed a 12-week program followed by a less intensive maintenance phase, resulted in more significant improvements in wrist circumference, parental-reported HRQoL, and smaller increase in FBS levels, compared to the conventional dietary counseling group.