1. Background

During adolescence years, social, cultural, familial, and friends’ expectations, as well as physical maturation, hormonal changes, and puberty-related changes, lead to periods of uncertainty, self-disbelief, and hopelessness. These factors affect the individual’s health and well-being and may lead to risky behaviors (1).

Some studies have shown that spiritual well-being can play a protective role in the development of high-risk behaviors in adolescents (2, 3). In 1979, WHO considered spirituality as an important element of health along with biological, social, and psychological well-being (4).

A review of the literature indicates that spirituality is increasingly being considered a key solution to psychosocial problems (5). Although there are no reliable statistics on Iranian adolescents’ high-risk behaviors, some studies indicate an increase in such behaviors among Iranian youth (6). Significant negative correlations have also been reported between spiritual well-being and different types of high-risk behaviors (7, 8). Research has also shown significant relationships between spiritual well-being and other aspects of well-being (9, 10).

Studies have also suggested that some personality traits can lead to high-risk behaviors or poor well-being. Personality, as enduring patterns of perception, thinking, and behavior affects individuals’ interactions with others across different situations (11). It can be said that personality traits are good predictors of some specific behaviors. For instance, studies have shown a significant relationship between negative affectivity and the ability to resist alcohol consumption (12) and that individuals with disinhibited personality traits are more vulnerable to risky behaviors such as drug and alcohol abuse (13). In addition, lack of spiritual well-being has been found to be a significant predictor of maladaptive personality traits (14). People who have higher spiritual well-being are more aware of themselves and are more capable of dealing with problems (15). Spirituality may represent an important aspect of one’s personality that has not been explored (16). Although a number of studies have reported a positive relationship between spirituality and well-being, further studies are needed to ascertain the precise character of the relationships between spirituality and different aspects of well-being. In addition, limited studies have addressed the relationships between spirituality and dimensions of well-being, high-risk behaviors, and personality traits. The present study aimed to shed further light on the association between these variables among Iranian adolescents.

2. Objectives

Considering the scarcity of studies addressing the dynamic relationships between dimensions of well-being, high-risk behaviors, and personality traits, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between spiritual health and well-being dimensions, personality traits, and tendency to engage in high-risk behaviors among adolescents.

3. Methods

This is a cross-sectional descriptive study. The statistical population included all high school students aged 15 to 17 in the city of Tehran. Using the formula

The inclusion criteria were as follows: age between 13 and 17 years old, being a high school student, and willingness to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: any psychiatric or medical problems for which treatment or medication was required and a past history of hospitalization due to a psychiatric disorder.

3.1. Research Instruments

3.1.1. Spiritual Well-being Questionnaire

The 20-item Paloutzian-Allison Spiritual Well-being questionnaire (SWBQ) is designed to assess the spiritual and existential health of individuals. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire were examined in a study in Iran, confirming its content validity and reporting a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 (18).

3.1.2. Ryff and Keyes Psychological Well-being Questionnaire

The 18-item short form of Ryff and Keyes questionnaire assesses six factors related to psychological well-being, i.e., self-acceptance, environmental mastery, positive relationship with others, purpose in life, personal growth, and independence (19). The sum of scores of these six factors comprises the total score for the scale. In a study in Iran, in a sample of 987 individuals, the Cronbach’s alpha for the six factors and the total scale were 0.51, 0.76, 0.75, 0.52, 0.73, 0.72, and 0.71, respectively (20).

3.1.3. Keyes Social Well-being Questionnaire

This 33-item questionnaire was designed to measure five dimensions of social well-being, i.e., social integration, social contribution, social coherence, social actualization, and social acceptance (21). The internal consistency coefficients for the factors were 0.57, 0.69, 0.81, 0.75, and 0.77, respectively. In a study in Iran, the Cronbach’s alpha for the dimensions and the total scale were 0.77, 0.74, 0.73, 0.74, 0.76, and 0.76, respectively (22).

3.1.4. Physical Health Questionnaire

The initial version of this questionnaire was introduced in 1987. In 2005, a more comprehensive evaluation of the questionnaire resulted in a 14-item questionnaire measuring the four dimensions of physical health, including headache, sleep disturbance, gastrointestinal, and respiratory problems (23). In a study in Iran, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the four factors and the total scale were 0.79, 0.66, 0.77, 0.71, and 0.81, respectively (24).

3.1.5. Iranian Adolescent Risk-Taking Scale (IARS)

This scale is designed to assess Iranian adolescents’ risk-taking behavior. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the total scale, dangerous driving, violence, smoking, drug abuse, drinking, relation with opposite sex, and sexual relationship and behavior were 0.94 l, 0.74, 0.78, 0.93, 0.93, 0.90, 0.83, and 0.87, respectively (25).

3.1.6. Personality Inventory for DSM-5 Personality Disorders (PID-5)

This inventory was developed to assess maladaptive personality traits based on DSM-5 dimensional model. It covers 25 personality traits in five domains, including negative effect, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism. The Cronbach’s alpha for the domains ranged from 0.78 for disinhibition to 0.96 for detachment (26). The reliability of this inventory was evaluated in a sample of 1,396 Iranian students, and the overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were reported 0.93 for traits and 0.88 for domains (27).

3.1.7. Ethical Considerations

The Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences approved this study (approval ID: IR.IUMS.REC.1398.554).

4. Results

The sample consisted of 350 adolescents, 25 of whom were excluded from the study due to incomplete responses to research questionnaires. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Total | 325 |

| Average age | 16.28 |

| Minimum age | 15 |

| Maximum age | 17 |

| Standard deviation | 0.489 |

| Skewness | 0.498 |

| Elongation | -0.637 |

| Grade | |

| 10th grade | 140 (43.1) |

| 11th grade | 121 (37.2) |

| 12th grade | 64 (19.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 170 (57.7) |

| Female | 155 (52.3) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

The results of the study regarding the relationships between the study variables are shown in Table 2.

| Variable | Spiritual Well-being | Physical Well-being | Social Well-being | Psychological Well-being | High-risk Behaviors | Personality Traits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual well-being | 1 | |||||

| Physical well-being | 0.289** | 1 | ||||

| Social well-being | 0.395** | 0.149** | 1 | |||

| Psychological well-being | 0.447** | 0.233** | 0.401** | 1 | ||

| High-risk behaviors | -0.480** | -0.264** | -0.218** | -0.202** | 1 | |

| Personality traits | 0.382** | 0.299** | 0.271** | 0.465** | -0.356** | 1 |

a**, P < 0.01.

According to Table 2, the correlations between spiritual well-being and physical well-being, social well-being, psychological well-being, and personality traits are all significantly positive (P < 0.01). However, spiritual well-being has a significantly negative correlation with risk-taking behaviors variables (P < 0.01). High-risk behaviors also had a significantly negative correlation with spiritual well-being. Moreover, personality traits as a mediating variable had significantly positive correlations with all dimensions of well-being and a significantly negative correlation with high-risk behaviors.

The results of the correlations between high-risk behaviors and spirituality are shown in Table 3.

| High-risk Behaviors | Drug | Alcohol | Smoking | Violence | Sexual Relationship | High-risk Driving | High-risk Behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual Well-being | -0.353** | -0.403** | -0.293** | -0.421** | -0.361** | -0.245** | -0.480** |

a**, P < 0.01

The results show that spiritual well-being has significantly negative relationships with high-risk behaviors.

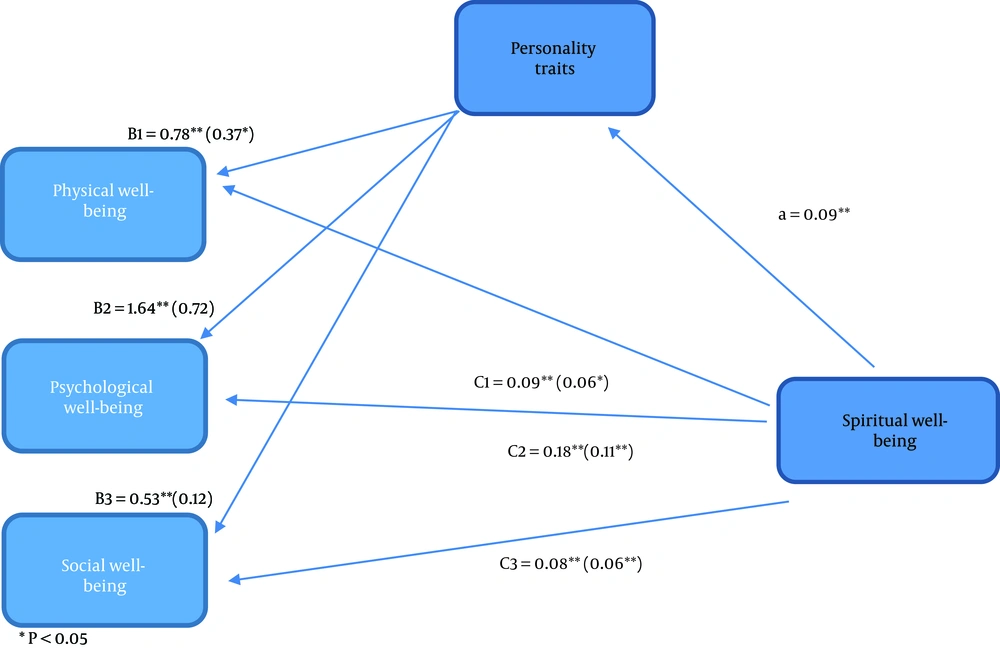

Structural equation was used to examine the mediating role of personality traits in the relationship between spiritual well-being and other study variables, the results of which are summarized in Figure 1.

According to Figure 1, there are significant correlations between spiritual well-being and other aspects of well-being (c). The numbers outside the parentheses show direct effects, and the numbers in parentheses show indirect effects of personality traits. Here, a-b1- b2- b3 represent regression coefficients, with numbers outside parentheses, indicating indirect effects with respect to the mediating variables (i.e., personality traits) and the numbers in parentheses, representing overall correlations (considering direct and indirect paths).

To examine the mediating role of personality traits in the relationships between spiritual well-being and high-risk behaviors, structural equation modeling was used, the results of which are shown in Figure 1.

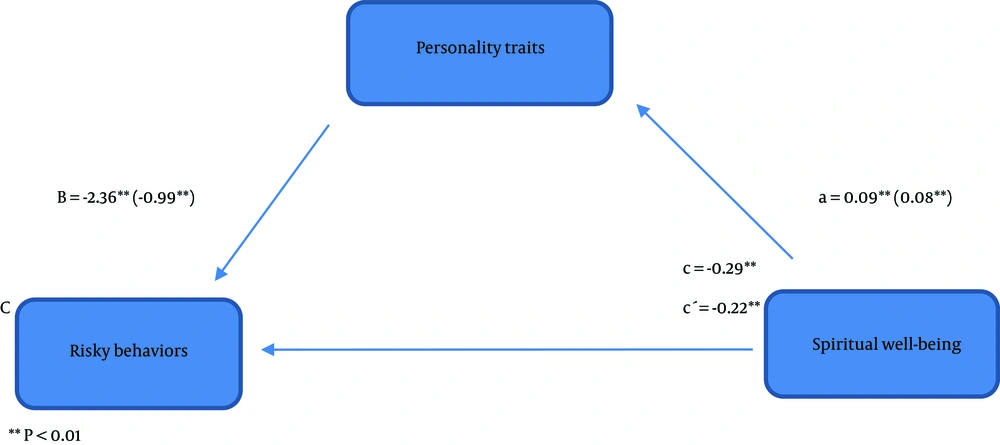

Figure 2 shows the structural relationships between spiritual well-being and high-risk behaviors with the personality traits as a mediating variable.

In Figure 2, (c) indicates a direct relationship, while (c’) indicates an indirect relationship. In the relationship between spiritual well-being and personality traits (a), and between personality traits and high-risk behaviors (b), the numbers outside of the parentheses show direct, while the numbers inside the parentheses indicate the overall direct and indirect relationships.

5. Discussion

The results confirmed the significant relationships between spiritual well-being and other aspects of well-being. Significant negative relationships were also observed between spiritual well-being and high-risk behaviors such as smoking, drug use, alcohol use, sexual behaviors, high-risk driving, and violent behaviors. The relationships between personality traits as a mediating variable and spiritual well-being and high-risk behaviors were significant.

The importance of spirituality in life has been supported by many studies. Kelly and Miller’s research has shown that spirituality is associated with various outcomes such as physical health and psychological well-being (28). A study by the Gallup International Institute on Adolescents from 1959 to 1993 showed that spiritual and religious variables played significant roles in reducing 57% of adolescents’ high-risk behaviors and suggested that spirituality was a constructive factor in adolescents’ lives (29). The results of the present study were also in line with the results of the studies that have shown the role of spirituality in reducing high-risk behaviors and improving physical and mental health (2, 3, 30). Also, it has been shown that spirituality plays a major role in reducing high-risk behaviors, improving emotional health, and preventing violence (31). Studies in Iran have also shown significantly negative correlations between spiritual well-being and high-risk behaviors. It can be concluded that the protective effects of spiritual factors can promote more positive social behaviors and reduce high-risk behaviors (31).

The results of this study also show that personality traits play important role in the tendency for high-risk behaviors. These findings are consistent with the results of other studies indicating that the risk of substance use is related to antagonism and impulsivity (32). Aspects of antagonism traits include tendency to ignore others’ needs, show deceitful and controlling behaviors, show cruelty, display grandiosity, and seek attention (33).

The results of a previous study also showed that the tendency to use alcohol is associated with negativity, antisocial tendencies, psychoticism, and disinhibition (34). Another study has shown that people who are more disinhibited and impulsive are more vulnerable to high-risk behaviors (35). The authors have reported that individuals who have traits such as irresponsibility, distractibility, impulsivity, abrupt response to stimuli, and excessive perfectionism are more vulnerable to risk-taking behaviors.

In addition, this study showed that personality traits were significantly correlated with variables of well-being and spirituality. Wilt et al. (36) have suggested that spiritual well-being is a variable that not only predicts other dimensions of well-being but also can predict personality effects. Spiritual/religious strategy can significantly affect life satisfaction, self-esteem, depression, and anxiety, which are aspects of psychological, social, and physical well-being. Based on the results of previous and present studies, spirituality can be considered a personality trait (36). Some studies, citing Allport’s theory, consider spirituality and spiritual well-being as aspects of one’s personality structure (16). Some authors have suggested that spiritual well-being is related to various aspects of well-being, including psychological well-being and personality, and that spirituality may represent an important aspect of human personality (37).

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of the present study are in line with the results of other studies on the relationship between spiritual well-being and mental health. This study shows that spirituality can positively affect one’s health and quality of life by influencing one’s beliefs and values. Changing the frameworks of human thinking and behavior can be an important factor in the health of one’s behavior. Spirituality leads to a reduction of high-risk behaviors by improving individuals’ psychological, physical, and social well-being. In addition, in line with the previous studies, personality traits have mediating effects on the relationship between spiritual well-being and high-risk behaviors. To further affirm the findings of the present study, it is suggested that the study should be replicated on samples with various age groups, socioeconomic status, and cultural backgrounds. It is also suggested that in future studies, other measurement methods and random sampling should be utilized.