1. Background

Like other developing countries, Iran has been experiencing an increase in the population of older people which is predicted to witness exponential growth in the coming decades (1). Therefore, there has been an increase in concerns about the different aspects of health in older people. Depression is a major health problem in old people which not only decreases function and quality of life but also causes early death. Along with all the other known contributing factors, psychosocial adversity has a great impact on the mind, causing depression in older adults (2). Stressful life events and difficulties such as losses, illness, disability, poverty, retirement, loneliness and diminished social relationships are responsible for depression (3).

Despite the advent of modernization in Iranian society, there exist a strong attachment between older adults and their children, which serves as a reliable source of support (4). Besides, religious beliefs and spirituality are deeply-rooted among Iranian older adults hence; this group is not expected to be more depressed (5). Nevertheless, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in community-dwelling Iranian older adults has been reported to be as high as about 60% (6). This is a significant rate in comparison with many other countries, even in the east such as 22% in Pakistan (7) and 11 - 57% in China (8). Depression can be closely related to the socio-cultural context. Therefore, no other source can better explain the nature of these factors than older adults who have experienced depression themselves.

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study was conducted to analyze their experiences with the help of qualitative methods of research.

3. Materials and Methods

Given the widespread knowledge on psychosocial factors associated with depression, the present study was conducted using directed qualitative content analysis which is a type of deductive content analysis generally used when there is considerable information available on the subject that a researcher wants to re-evaluate in a new community (9). First, a systematic search on literature was carried out using MEDLINE and Persian data banks including Iran psych, SID and Magiran and pertinent articles were selected. An analytical matrix was prepared with multiple categories, including social relationships and support, health status, life events, change of roles, and spirituality. The participants were selected using purposive sampling among the old patients (> 60 years) of the psychiatric clinics of a number of hospitals in different parts of Tehran. A list of patients who were diagnosed with depression by psychiatrists in the last six months was prepared. The researchers contacted the selected patients over phone, asking for interviews. Thereafter appointments with the willing patients were fixed. At the beginning of the interviews, the participants were briefed on the study objectives. Further, their right to participate in or withdraw from the study at any time was assured. They were assured of the confidentiality of their names and personal information as well. The willing participants then provided their written consent. Cognitive impairment was ruled out using the validated Persian version of the Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS). AMTS was first used by Hodkinson in 1972 (10, 11) with good validity (0.82 - 0.90) and reliability(0.87 - 0.92). The Persian version (12), had good discriminant validity (P < 0.01) and reliability (0.89).

Data were collected using semi-structured interviews held at the participants’ discretion either in their home, at the clinic, or at a nearby park. The interviews began with an open-ended question such as “How did you get depressed?” and continued with supplementary questions such as “Do you think there was something else that also affected your mood?” Then they were posed questions derived from those categories of the analytical matrix that they had not discussed spontaneously in the interviews. All the interviews were recorded, with participants’ consent and transcribed verbatim. The interview texts were reviewed several times and then transformed into meaning units and codes. The coding was carried out after each interview. The codes were then classified-based on the analytical matrix- and revised. The emerging codes that could not be included in the categories of the matrix formed new subcategories and categories based on the two researchers’ opinions. The comments of two other researchers were also taken into account and were used to revise the categories. To increase the rigor and trustworthiness of the data, maximum variation sampling was used to select participants from different genders, ages, ethnicities, and educational levels. In addition, some of the extracted codes were checked by members and, eventually, all the stages were scanned by an expert.

4. Results

The interviews were conducted from October 2014 to November 2015 with 12 depressed older adults aged between 60 and 80 years. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

| No. | Sex | Age | Education | Marital Status | Interview Dduration, min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 65 | MS | Married | 55 |

| 2 | M | 75 | MS | Married | 80 |

| 3 | F | 66 | Diploma | Married | 101 |

| 4 | F | 63 | Diploma | Married | 51 |

| 5 | F | 60 | Middle school | Married | 124 |

| 6 | M | 61 | Primary school | Widower | 102 |

| 7 | M | 63 | Associate degree | Married | 41 |

| 8 | F | 80 | Illiterate | Widowed | 62 |

| 9 | F | 69 | Illiterate | Married | 41 |

| 10 | M | 69 | Middle school | Married | 47 |

| 11 | M | 79 | Primary school | Married | 46 |

| 12 | F | 70 | Primary school | Divorced | 33 |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male.

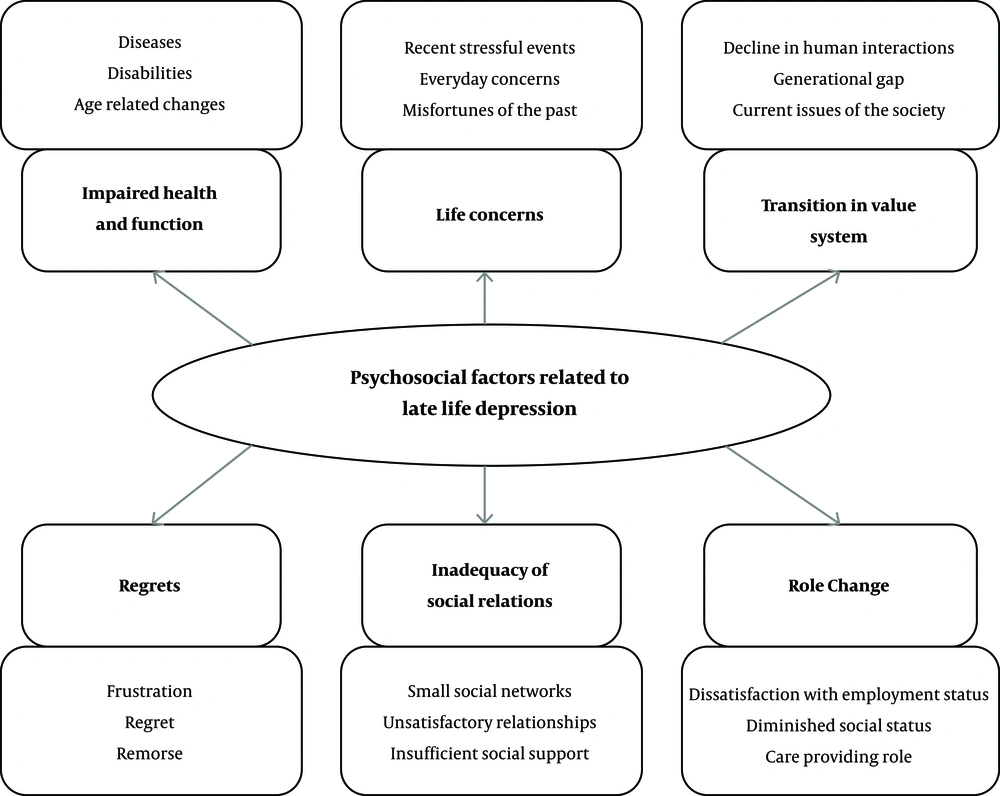

The results of this study demonstrate individual perceptions of depression and the psychosocial factors contributing to depression in Iranian older adults. A total of 534 codes were extracted from the analysis of the interviews, which were reduced to 42 subcategories, 17 categories, and six themes after classification based on the analytical matrix and abstraction. The six themes shown in Figure 1, are explained below.

4.1. Transition in Value System

The participants’ perception of what had led them to depression referred partially to the changes that had recently occurred in society. The category of decline in human interactions involved a decline in moral values and a loss of interest in other people. The participants believed that the spread of lies and hypocrisy had corrupted human interactions. This disheartened the participants. A 63-year-old woman said: “It annoys me very much. The lies you hear, the hypocrisy you see. Why do people have to be so hypocritical? Why don’t they just show the truth of their life as it is?”

Some of the participants believed that the loss of interest in other human beings had contributed to their depression. A 65-year-old woman said: “People have changed, emotionally-speaking; they’ve become so cold toward each other, compared to the past.”

4.2. Role Changes

Some participants believed that dissatisfaction with their current employment status was a factor that led to depression, as most of the older men complained of early or unwanted retirement. A 69-year-old man said: “I had a very good position at my job. Unfortunately, I retired too soon and now that I’m retired, I live an unhappy life.”

The diminished status of older adults in family and society was another factor. An 80-year-old woman said: “Everybody has become indifferent, or what are these nursing homes for? We begged our grandmothers to come and live with us, but it’s no longer like that.” She also talked about her reduced contribution as a decision-maker in the family.

The burden of providing constant care was also noted as a reason for depression by the participants. A 76-year-old man discussed the pressure of taking care of a child with mental disorder: “Our life has been disrupted by taking care of this son of ours; my wife and I take turns attending to him.”

4.3. Life Concerns

The concerns and struggles of life comprised a major theme. The death of loved ones was one of them. A 66-year-old woman narrated how she got depressed: “About a year ago, my son died; this is a pain I can never forget.”

The participants also noted other adverse family events-such as a child’s illness, divorce, and spousal infidelity. According to a 60-year-old woman, it was her husband’s care providing: “I never had a problem until I recently realized that my husband has been cheating on me”.

Many of the participants believed that their past misfortunes affected their current mood. A 79year-old man talked about how he was deprived of the warmth of a close-knit family in his childhood: “I grew up in a hostile environment full of fights, because my father had remarried and hadn’t stayed with my mother.” The participants had various daily concerns; financial concerns were almost always there. A 69year-old man said: “I’ve rented a small apartment and now it’s nearly that time of the year to sign a new contract. Just remembering it makes me anxious. The landlord may ask for some extra money or, if not, then evacuation.”

4.4. Inadequacy of Social Relationships

The participants complained of a limited social network such as having no spouse and living alone, unavailability of a close friend available, and having too little communication with one’s children, relatives, friends, and even neighbors. An 80-year-old woman said: “Nobody lives with me. I have to go outside to find someone to talk to. No one rings the doorbell anymore.”

A 65-year-old woman said that she had limited relationships with the neighbors: “I’d love to say hello to at least one of my neighbors every now and then, or when I go for a walk in the park, actually talk with someone. But people don’t like that”.

Most participants were unsatisfied with the quality of their emotional relationships with their spouses. A 66-year-old woman said: “In all the 40 years, I’ve never been able to get anything off my chest with my husband. I’ve always kept my thoughts to myself.”

The participants believed that inadequate social support from the spouse, children, relatives and even the neighbors was one of the main contributors to depression. A 66-year-old woman talked about her unmet expectation to receive support from her children during her illness: “I would’ve loved for my daughter to just come and bring me a pot of soup, or to just come and tell me: ‘Mom, I’ve come to see you’ It would’ve been enough if she’d just come here and asked, ‘Is there anything I can do for you?’

4.5. Regret

Regretting past mistakes- such as a poor marriage and divorce and having a sense of guilt in some cases were discussed by some participants. A 79-year-old man confessed his regret for his poor marriage: “I felt too lonely, so I went and married a widow with two children. Since then, I haven’t been happy a day in my life. It’s been a catastrophe.” A 61-year-old man regretted his bad behavior toward his wife: “I was so terrible. I thought I must beat my wife like my father had beaten my mum. There was no one to guide me, to tell me that your wife is your companion, she shares your life. Nobody told me any of that stuff.”

4.6. Impaired Health and Function

Many of the participants believed that decline in health and strength and having diseases and medical conditions, associated with old age, have a role in their depression. A 79-year-old man said: “Nothing in my body functions as it should. My lung is damaged. I have diabetes too, and even eating regular food injures my mouth. I have all sorts of pain. I’ve visited many doctors. I take a lot of analgesics and sedatives. I can’t live a second without this spray.” Some of the participants expressed their discomfort about how their medical problems had taken away their independence and function. A 70-year-old woman narrated: “My broken leg bothers me. I was too worried about my leg. It’d gotten on my nerves actually. I couldn’t even stand up to cook something for myself.” An 80-year-old woman complained: “Well, I can’t eat anything and all my muscles have weakened. I was once healthy and active, but now I am just a skeleton.”

5. Discussion

The study showed that, the categories of the analytical matrix extracted from the literature review, including life events, role changes, inadequacy of social relationships and impaired health and function contributed to depression. Besides, new categories of transition in value system and regret, which also emerged during the interviews, had prominent roles in inflicting old people with depression.

Transition in value system was a new theme that emerged from the experiences of the depressed Iranian older adults. As some sociological studies have mentioned (13), in the process of modernization, human relations and value frameworks have changed; older adults having grown up in a traditional society expect the old principles and values to prevail. They conclude that people’s kindness and interest in each other and their moral values have declined. The gap that has emerged between the younger and the older generation through the process of social transition of Iran, is a point of similarity between this study and Mui’s study (14). Mui found that the cultural gap between immigrant older adults and their children contributes to depression.

Many studies have noted the major role of life concerns and stressful events causing depression (2, 3). Losses such as grief, especially for the loss of spouse or child, were important factors. According to the psychodynamic theory, the incidence of depression as a reaction to grief is caused by the older adult’s failure to express the negative emotions resulting from the loss and is most frequently observed in those who do not express their feelings adequately (15).

Several studies have shown that inadequate social relationships and loneliness contribute to depression in old age (16). This fact was confirmed by the experiences of our participants Furthermore, the quantity and quality of relationships with one’s family mattered the most. Krsteska and Pejoska-Gerazova (17), revealed that dissatisfaction with the marital relationship, lack of affection for the spouse, continuous conflict in relationship, and the sense of being neglected and not loved were some of the factors lead to depression in older adults. This is also consistent with the findings of the present study. The present generation of Iranian older adults has had mostly traditional marriages with no previous long-term familiarity with the spouse. Since traditional values insist on preserving the marriage, in some cases, couples lived together for years until death in spite of great incompatibility and a lack of mutual understanding. Some of our participants believed that such unsatisfactory alliance manifested in a struggling relationship or resulted in emotional separation. This eventually failed to meet the couple’s needs and might have led to their depression. However, an intimate and affectionate relationship with the spouse moderates the adverse effects and other risk factors such as physical disabilities (18). Furthermore, the quantity and quality of relationships with children, relatives and even neighbors and friends were also important. This suggests the severe dependence of Iranian older adults on family and the immediate community around them. Several studies in eastern societies have confirmed the huge role of these relationships; For Korean older adults, maintaining family relationships is considered a key factor in preventing depression (19). One of the functions of social networks is to provide social support, and the accomplishment of this function prevents and even helps treat depression (20). The participants believed that inadequate social support, especially emotional support, had contributed to depression.

Both the objective aspects of diseases and decline in function and the individual’s subjective perception of impaired health status may lead to depression (2). According to Ravanipour et al. (21) maintaining independence and having function comprise an integral part of the perception of power in Iranian older people. So, these conditions may act as deficit in the sense of power and lead to depression.

A good relationship with God and spirituality protects individuals against depression, however according to Braam et al. showed (22), the fear of God, an unsatisfactory relationship with Him and a sense of unmet spiritual need can be considered as factors leading to depression in older adults. Nevertheless, the majority of the participants revealed a good relationship with God and confirmed that it brought them peace and helped them cope with the struggles of life.

Since depression is a gradual process, the participants may be unable to differentiate the temporal course of the events. Therefore, although the interview questions emphasized on the initiation of depression in the participants, it was impossible for the researchers to exactly distinguish between the primacy and recency of their experiences. This failure to distinguish the causes from the effects is a limitation of the present study. Moreover, as in other qualitative studies, the results of this study may be limited to the population under study and cannot be entirely generalized to other communities.

5.1. Conclusion

In big cities of Iran, where modernity dominates people’s lives, older adults are confronted with gaps in family relationships and support. Therefore, the current generation of older adults feels lonely in the face of life struggles. Furthermore, older adults are still seeking their lost status in our traditional society that has undergone changes in term of structure and values. They are unable to handle the process of aging, adopting disappointed views in some cases. The accumulation of these factors makes it more difficult for them to cope with their current life problems and this contributes to depression. An increase in the awareness of community and family values among the Iranian people -from the perspective of older individuals- is preparing the society to deal more effectively with the phenomenon of aging, and the needs of older adults. This may contribute to the betterment of mental health of older people. It seems that the improvement of social centers for older adults and the provision of culturally compatible formal support services can partially compensate for the emerging lack of family support. Thus, it may result in decreasing incident of depression in this age group.