1. Introduction

Visceral artery aneurysms (VAAs) are rare lesions among other vascular diseases with an incidence of 0.01 - 2%, although the thorough incidence is not known because of the asymptomatic nature of VAAs (1). Because of their high risk for rupture (30 - 40% of cases), which is an emergent and potentially life threatening situation, they can cause high morbidity and mortality. Small VAAs have no symptoms (2), but large ones can have symptoms such as pain, bleeding and hypotension (3) and they occur usually in splenic, hepatic, superior mesenteric, gastroduodenal and small pancreatic arteries (4).

The first case of hepatic artery aneurysm (HAA) was reported in 1809 in a dead patient (5). Some studies reported a 20% incidence for HAAs that can occur intrahepatic (because of inflammation and trauma) or extrahepatic (because of atherosclerosis) (6, 7). HAAs are the second most frequent aneurysms after splenic artery aneurysm and their rupture is life threatening (8, 9).

In the past, many VAAs were diagnosed after rupture (1), but in the recent decades, advances in rapid cross-sectional body imaging, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) has enabled us to identify them earlier (1, 2, 6). The gold standard for diagnosis and pre-operative planning is digital subtraction angiography (5).

Repair is recommended in aneurysms greater than 2 cm in diameter (5). Anatomic suitability, clinical presentation, underlying etiology, general health status and comorbidity factors determine the treatment method. Before using endovascular techniques, for many years, open surgical treatment was the only treatment method (10, 11).

At present, endovascular techniques provide an alternative method in which good results with low morbidity and recurrence rates have been reported (11). In cases of intracranial aneurysm, embolization with coils has been increasingly used for treatment. Studies showed that it is a safe method for patients with an unruptured aneurysm or aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (12).

Herein, we present a patient with a rare huge hepatic artery aneurysm (95 mm × 83 mm diameter) that caused recent abdominal pain and abdominal mass. She was treated successfully with endovascular coil embolization (with as many as five coils).

2. Case Presentation

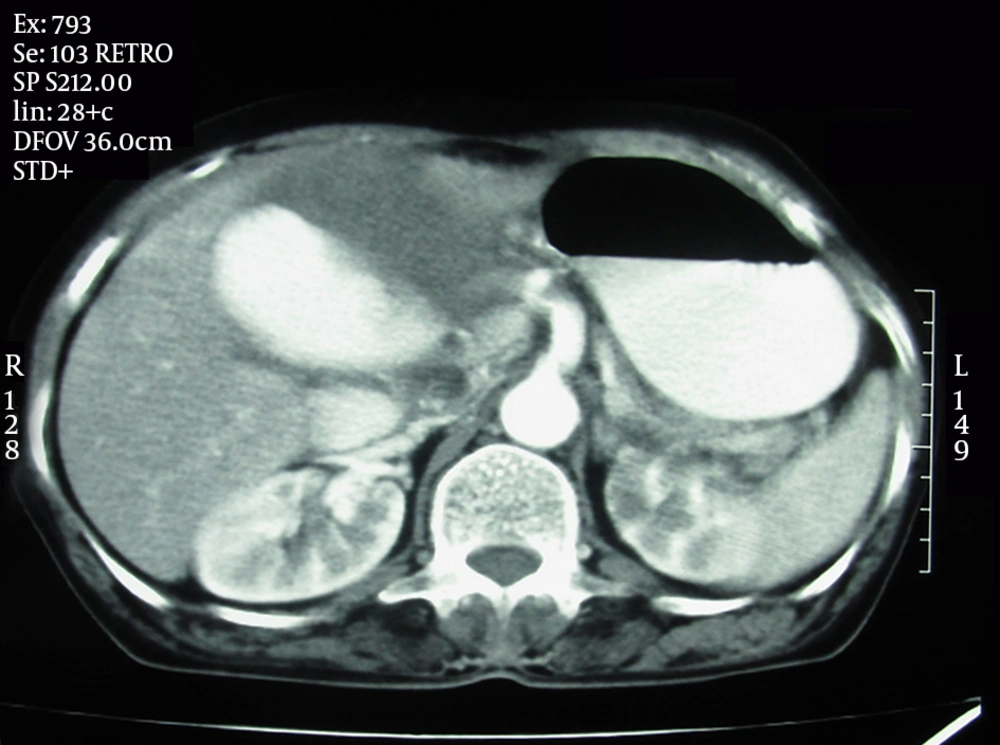

A 67-year-old woman was admitted for recent right upper abdominal pain that began 2 weeks ago. The pain was non positional, sustained and unrelated to eating. There were no other abdominal symptoms. The patient had no significant past medical history. During the initial physical examination, there was a pulsatile large mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. In duplex ultrasound, a huge arterial aneurysm was detected in the hepatic artery with mural thrombosis. Computerized tomogram (CT) with contrast medium showed a huge aneurysm (95 mm × 83 mm in diameter) in the hepatic artery that contained mural thrombi in the aneurysmal sac (Figure 1).

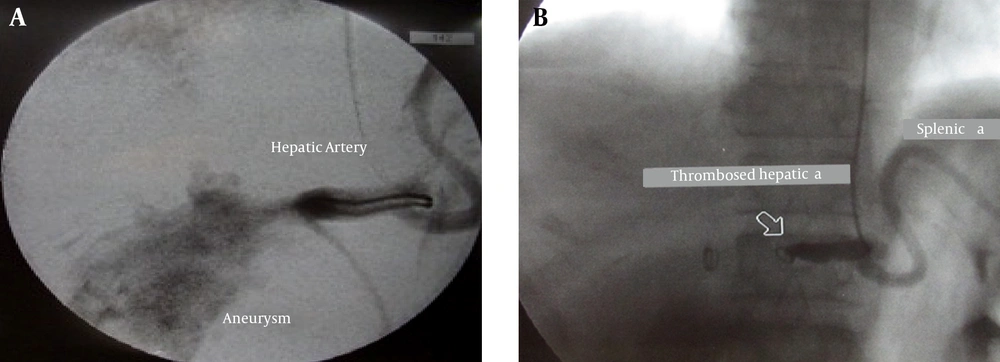

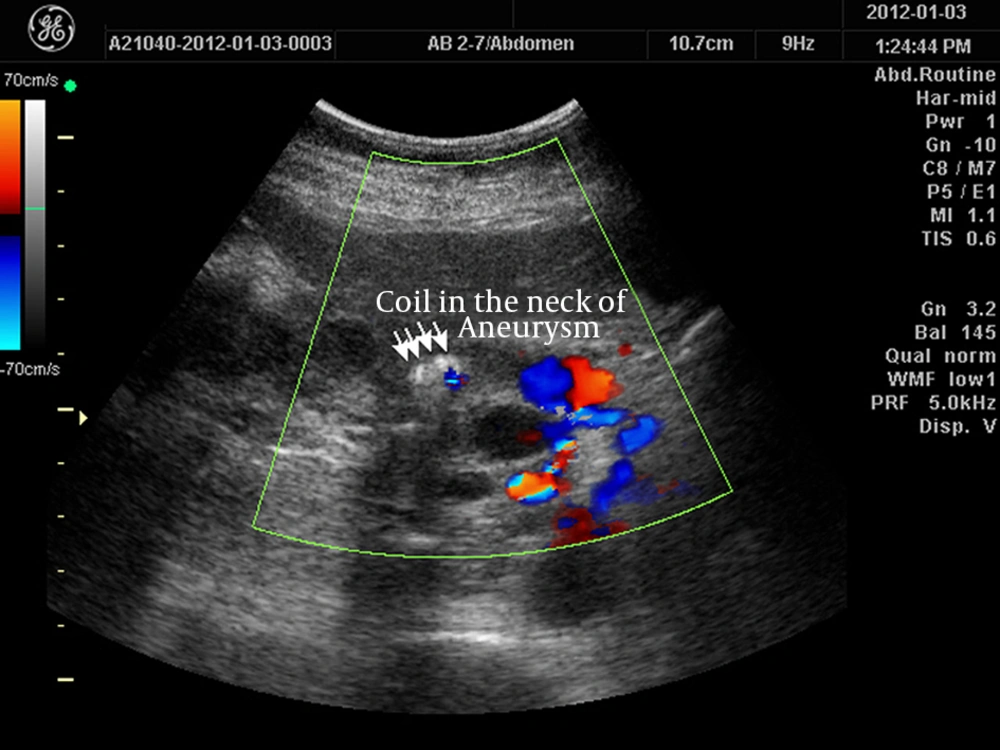

The patient underwent endovascular technique. Transfemoral celiac artery catheterization was not successful so the trunk was catheterized via the left brachial artery approach. In aortic angiography, the celiac artery orifice and superior mesenteric artery were narrow too. Sonography was used to determine the exact position of the catheter in the celiac artery orifice. Then selective hepatic artery catheterization was done. The tip of the catheter (JR4 6F) was placed in the hepatic artery distal to the gastroduodenal artery. Three coils (MR eye Embolization coil 8 mm × 5 cm) were delivered in the aneurysm and two others were delivered in the hepatic artery (neck of aneurysm). The aneurysm began to thrombose and eventually thrombosed completely after 4 to 5 minutes (Figure 2). The patient was uneventful after the procedure and pulsation of the mass disappeared. Two days after the procedure, ultrasound showed complete thrombosis of the aneurysm (Figure 3). Liver function tests were normal after the procedure and 3 days after that. The patient was discharged with good general condition.

3. Discussion

HAA is an uncommon vascular disease (13). Approximately 20% of all visceral aneurysms are HAAs (6). They usually have no symptoms (5) but some patients with HAA have abdominal pain (55%), gastrointestinal hemorrhage or hemobilia (up to 46%), and obstructive jaundice (7). Our patient has a huge hepatic artery aneurysm. Atherosclerosis, vasculitis, fibromuscular dysplasia and cystic medial necrosis are common causes for HHAs (7). Selective angiography of the celiac axis and superior mesenteric artery, CT scan and ultrasound are diagnostic methods for this aneurysm (3, 14). Open surgical repair or follow up of the patients with serial imaging are traditional methods for managing VAAs (10), but some studies reported a 30% to 50% mortality rate for the surgical treatment (5, 6). Nowadays, we can use various methods for VAA treatment such as mentioned conventional open surgery, laparoscopic surgery, and endovascular treatment (3). Endovascular (or percutaneous) approach uses different methods and instruments such as coil, cyanoacrylate, thrombin and stent graft (3). Endovascular treatment may have better outcomes in both elective and emergency cases because it is less invasive (15). Site and morphology of VAAs determine the feasibility of embolization technique for the patient (3). In cases with difficult anatomy, coil embolization is used due to its relative simplicity (15). In our patient with a huge hepatic artery aneurysm that was high risk for surgery, endovascular coil embolization was selected. In this patient, five coils were used for embolization of the hepatic artery aneurysm. According to this case report and the procedure applied, it seems that coil embolization is a safe and effective procedure to treat hepatic artery aneurysm even in huge sizes.