1. Background

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has spread widely around the world. Studies indicate that children are less affected than adults, exhibiting milder symptoms and lower mortality rates (1, 2). However, the clinical and epidemiological characteristics and the definitive treatment protocol in children are not yet clear. Li et al. highlighted this significant knowledge gap and attempted to introduce and categorize these symptoms in their systematic review of 96 case studies on children (3). Lai et al.'s study notes that few studies have addressed the characteristics and clinical manifestations of children with COVID-19 (4). In children, shock has also been reported as a complication of COVID-19, treated under the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) (5). Shock occurs in up to 67% of patients in intensive care and has been associated with high mortality (6). Close monitoring of cardiac output (CO), intravascular volume (IVV), and hemodynamic parameters is essential for these severe cases, which typically require mechanical ventilation (7). In recent years, there has been a gradual reduction in the use of pulmonary artery catheters and thermodilution measurement of CO (8), and less invasive methods (9) have replaced them. However, these alternatives have not been satisfactory due to a lack of accuracy. Therefore, there is an urgent need for reliable and cost-effective non-invasive devices for CO monitoring (10). The ultrasonic cardiac output monitor (USCOM) is a non-invasive device that determines a person's cardiac output using continuous wave Doppler ultrasound (11). Introduced in 2001, USCOM is now used in a wide range of clinical settings and plays a significant role in monitoring intensive care (12). Although preload, contractility, systemic vascular resistance (SVR), stroke volume (SV), and CO can also be measured by echocardiography, this method requires a skilled and specialized physician (13). The accuracy and reliability of USCOM have been confirmed in various studies (12, 13). In this study, we present the results obtained from the USCOM device and other clinical findings of COVID-19 patients.

2. Objectives

The current study aims to present the clinical and laboratory manifestations of children with COVID-19 and to use a USCOM device for hemodynamic assessment to record and review their clinical information. The research questions are: (1) what are the clinical and laboratory results of children with COVID-19? (2) what is the hemodynamic status of children with COVID-19 using a USCOM device? (3) what treatments have been considered for children with COVID-19, and what have been the results?

3. Patients and Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in a public hospital in Iran. Children infected with COVID-19 who visited this facility between September and October 2022 were included in the study. Confirmation of the COVID-19 diagnosis in these patients was done by one of the following methods: Lung CT scan, real time-PCR test, or serology. Twenty-two patients who agreed to participate in the study and completed the informed consent form were selected as samples. All patients were well-informed about the procedures and the potential side effects. The Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences approved this study. In addition to completing the informed consent form, patients were assured that their data would be published without revealing their identities.

Inclusion criteria included all children under 18 years of age and older than one month who were hospitalized in the PICU, treated with the diagnosis of COVID-19, and had hemodynamic instability in the evaluations. They were diagnosed with COVID-19 according to the final diagnosis in the medical record. Exclusion criteria included age under one month, hemodynamic stability, and children with other concurrent diseases or underlying heart disease. Data related to tests, clinical evaluations, and imaging findings of these patients were extracted from their medical records. The data was collected using a form whose validity was confirmed by experts. This form included the patient's demographic, clinical, and laboratory information, as well as the treatment and medication administered.

A USCOM device was used to check the hemodynamic data of the patients, and this evaluation was done by a specialist doctor. The evaluation of each patient took a few minutes, measuring the following items: Corrected flow time (FTC) (preload), peak velocity (VPK) (contractility), and SVR. The operators who performed the USCOM assessments were pediatricians and PICU fellows who had been well trained to work with the device and had several months of experience. Data analysis was presented using descriptive statistics and in the form of tables and graphs. All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

4. Results

In this study, we reported 22 pediatric cases infected with coronavirus who were admitted to a public hospital in Iran. Ten of them were girls and twelve were boys. The youngest was 3 months old and the oldest was 14 years old. Most of the children were between 1 - 5 years old and 5 - 10 years old. Table 1 shows the demographic information of these patients.

| Population Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Boy | 12 (54.5) |

| Girl | 10 (45.5) |

| Total | 22 (100) |

| Age | |

| Under 1 year | 4 (18.1) |

| 1 - 5 | 7 (31.8) |

| 5 - 10 | 7 (31.8) |

| Above 10 years | 4 (18.1) |

| Total | 22 (100) |

Characteristics of the Sample Population

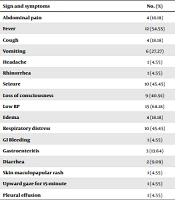

Table 2 shows the signs and symptoms observed in children. Various symptoms developed in the children, with the most commonly observed being low back pain (N = 15), fever (N = 12), seizures (N = 10), respiratory distress (N = 10), and low consciousness (N = 9). All percentages presented in the table are based on the total number of patients.

| Sign and Symptoms | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 4 (18.18) |

| Fever | 12 (54.55) |

| Cough | 4 (18.18) |

| Vomiting | 6 (27.27) |

| Headache | 1 (4.55) |

| Rhinorrhea | 1 (4.55) |

| Seizure | 10 (45.45) |

| Loss of consciousness | 9 (40.91) |

| Low BP | 15 (68.18) |

| Edema | 4 (18.18) |

| Respiratory distress | 10 (45.45) |

| GI Bleeding | 1 (4.55) |

| Gastroenteritis | 3 (13.64) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (9.09) |

| Skin maculopapular rash | 1 (4.55) |

| Upward gaze for 15-minute | 1 (4.55) |

| Pleural effusion | 1 (4.55) |

Signs and Symptoms of Patients

Table 3 provides information related to examination and laboratory findings as well as USCOM results.

| Feature and Title | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Examination & laboratory finding | |

| WBC (mm3) | 11518.2 ± 5761.8 |

| Lymph % | 19.2 ± 11.4 |

| Segs % | 74.8 ± 14.3 |

| Hb (g/d) | 10.9 ± 1.9 |

| Plt (mm3) | 250909.1 ± 180022.5 |

| ESR (mm) | 22.2 ± 18.8 |

| CRP (mm) | 37.3 ± 26.0 |

| D-dimer (ng/m) | 3415.4 ± 5249.3 |

| PT (se) | 14.9 ± 3.0 |

| PTT (se) | 45.5 ± 26.8 |

| INR (index) | 1.3 ± 0.5 |

| Troponin (ng/L) | 352.1 ± 769.4 |

| Blood pressure-systole (mmHg) | 75.4 ± 12.5 |

| Blood pressure-diastole (mmHg) | 50.8 ± 13.0 |

| USOM results | |

| SVRI (ds cm-5 m2) | 743.1 ± 86.3 |

| VPK (m/s) | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 112.0 ± 12.2 |

| FTC (ms) | 367.1 ± 20.4 |

| Duration of drug use | |

| Duration of norepinephrine | 6.6 ± 4.9 |

| Duration of epinephrine | 7.5 ± 4.0 |

| Duration of hospitalization (days) | 16.5 ± 12.3 |

Examination, Laboratory, and Ultrasonic Cardiac Output Monitor Finding

Most patients had lymphopenia and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Six patients were intubated. Antiviral treatment, antibiotics, and supportive care were provided for the patients. Except for two cases, all other patients were discharged after clinical recovery. All of these patients had low systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI), and six of them had normal blood pressure and were not treated with inotropic drugs. The average length of hospitalization was about 16.5 days. The information related to all patients is presented separately in Table 4.

| Title | Age | Gender | Symptoms and signs | Chest CT Scan | WBC (mm3) | Lymph % | Segs % | Hb (g/d) | Plt (mm3) | ESR (mm/h) | CRP (mg/L) | D-dimer (ng/m) | PT (s) | PTT (s) | INR (index) | B/C | Troponin (ng/L) | COVID-19 PCR | COVID-19 serology (index) | SVRI (ds cm-5m2) | VPK (m/s) | Heart rate (bpm) | FTC (ms) | Blood pressure (mmHg) | Duration of norepine phrine (day) | Duration of epinephrine (day) | Duration of hospitalization (day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient #1 | 9 | Boy | Abdominal pain, vomiting, cough, generalized tonic colonic seizure, loss of consciousness, GI bleeding, acral edema, low blood pressure | Peripheral ground glass opacities due to COVID-19 | 3700 | 37 | 59 | 13.8 | 107000 | 25 | 26 | 12715 | 18 | 69 | 1.7 | Neg | 1998 | Neg | IgM = 0.1, IgG = 0.2, (neg) | 632 | 0.9 | 107 | 369 | 75/31 | 4 | 4 | 15 |

| Patient #2 | 10 | Girl | Abdominal pain, headache, fever, vomiting and diarrhea, acral edema, low blood pressure | Mild pleural effusion and ground glass opacities | 7500 | 5.6 | 92 | 10.5 | 87000 | 58 | 62 | 2413 | 16 | 47 | 1.4 | Neg | 331.4 | Pos | IgM = 1.3, IgG=1.2, (pos) | 802 | 1.3 | 104 | 372 | 71/46 | 6 | 4 | 18 |

| Patient #3 | 7.5 | Girl | Fever, vomiting, skin maculopapular rash, epigastric abdominal pain, acral edema, low blood pressure | Peripheral ground glass opacities dominant in left lower lobe due to COVID-19 | 5800 | 20 | 71 | 10 | 102000 | 50 | 59 | 4291 | 13 | 32 | 1 | Neg | 86.6 | Neg | IgM = 0.8 → 1.3, IgG = 0.9 → 1.2, (pos) | 620 | 1.9 | 148 | 403 | 67/53 | 5 | - | 10 |

| Patient #4 | 7 | Boy | Fever, rhinorrhea, diarrhea, generalized tonic colonic seizure, low blood pressure | No significant data | 2600 | 35 | 54 | 11.8 | 177000 | 17 | 72 | 1538 | 13 | 27 | 1 | Neg | 121.9 | Neg | IgM = 0.3 → 1, IgG = 0.3 → 1.1 | 720 | 1.3 | 110 | 380 | 70/60 | 2 | - | 5 |

| Patient #5 | 13 | Girl | Fever and cough, movements suspected of seizures, loss of consciousness, periorbital and acral edema, low blood pressure | Peripheral ground glass patchy opacities due to COVID-19 and Evidence of aspiration pneumonia | 8300 | 17 | 77 | 14.2 | 280000 | 58 | 27 | 3317 | 15 | 37 | 1.3 | Neg | 17 | Neg | IgM = 0.1 → 0.9, IgG = 0.3 → 0.8 | 880 | 0.85 | 108 | 344 | 68/56 | 14 | 2 | 14 |

| Patient #6 | 5 | Girl | Abdominal pain, vomiting, status tonic colonic seizure | Mild peripheral ground glass patchy opacities | 13000 | 45 | 50 | 11.7 | 419000 | 10 | 24 | 23000 | 14 | 28 | 1.2 | Neg | 29 | Neg | IgM = 0.6; IgG = 1.5, (pos) | 747 | 1.4 | 94 | 346 | 65/45 | 4 | - | 14 |

| Patient #7 | 7 | Girl | Cough, atonic seizure, respiratory distress, loss of consciousness, low blood pressure | Peripheral ground glass opacities due to COVID-19 | 28000 | 17 | 75 | 11.3 | 123000 | 1 | 21 | 757 | 13 | 37 | 1 | Neg | 21 | Neg | IgM = 0.1, IgG = 0.2, (neg) | 765 | 1.2 | 103 | 322 | 84/40 | 5 | - | 10 |

| Patient #8 | 4 | Boy | Fever, upward gaze for 15-minute, loss of consciousness, low blood pressure | Ground glass opacities and upper left lung collapse | 10000 | 21 | 75 | 11.2 | 167000 | 10 | 30 | 890 | 13 | 29 | 1 | Neg | 1.5 | Neg | IgM = 0.3, IgG = 1.2, (pos) | 713 | 1.3 | 105 | 370 | 77/44 | 7 | - | 15 |

| Patient #9 | 0.25 | Girl | Fever, gastroenteritis, loss of consciousness, low blood pressure | Peripheral ground glass opacities due to COVID-19 | 11600 | 29 | 59 | 9.2 | 110000 | 7 | 1 | 2524 | 17 | 49 | 1.7 | Neg | 151 | Neg | - | 630 | 1.4 | 134 | 370 | 65/52 | 7 | - | 16 |

| Patient #10 | 14 | Girl | Fever, gastroenteritis, low blood pressure | White lung, pleural effusion | 6300 | 17 | 80 | 11.3 | 183000 | 56 | 60 | 6100 | 15 | 34 | 1.3 | Neg | 1325 | Neg | - | 614 | 0.8 | 110 | 380 | 60/30 | 20 | 18 | 60 |

| Patient #11 | 14 | Boy | Tonic colonic seizure, loss of consciousness, low blood pressure | Peripheral ground glass patchy opacities due to COVID-19 | 16000 | 6 | 90 | 13 | 391000 | 3 | 1 | 3115 | 13 | 31 | 1 | Neg | 2984 | Pos | - | 794 | 1.2 | 106 | 344 | 68/46 | 7 | - | 23 |

| Patient #12 | 1.5 | Boy | Fever, respiratory distress, low blood pressure | Opacities highly suggestive for COVID-19 | 10400 | 14 | 83 | 11.2 | 140000 | 37 | 45 | 1818 | 16 | 66 | 1.4 | Candidate | 29 | Pos | IgM = 0.7, IgG = 0.1, (neg) | 792 | 1.1 | 121 | 345 | 55/35 | 8 | - | 32 |

| Patient #13 | 1.5 | Boy | Fever, respiratory distress, pleural effusion, low blood pressure | Peripheral ground glass opacities due to COVID-19 | 13200 | 12 | 84 | 8.9 | 349000 | 10 | 40 | 614 | 14 | 28 | 1.1 | Neg | 0.1 | Neg | IgM = 0.2, IgG = 0.3, (neg) | 580 | 1.9 | 110 | 328 | 86/47 | 4 | - | 26 |

| Patient #14 | 7 | Boy | Fever, respiratory distress, loss of consciousness, low blood pressure | Ground glass opacities due to COVID-19 | 13900 | 2 | 92 | 12.6 | 257000 | 17 | 32 | 998 | 22 | 120 | 2.4 | Neg | 37 | Neg | - | 713 | 1.3 | 105 | 370 | 77/44 | 7 | - | 25 |

| Patient #15 | 1 | Boy | Vomiting, status epilepticus, loss of consciousness, low blood pressure | Opacities due to COVID-19 and aspiration pneumonia | 6700 | 23 | 43 | 8.6 | 293000 | 17 | 2 | 837 | 13 | 30 | 1 | Neg | 11.9 | Neg | - | 830 | 1.4 | 123 | 376 | 65/50 | 4 | - | 24 |

| Patient #16 | 3 | Boy | Vomiting, tonic colonic seizure, gastroenteritis, low blood pressure | Opacities due to COVID-19 | 11700 | 36 | 86 | 11.8 | 303000 | 9 | 13 | 398 | 13 | 30 | 1 | Neg | 589 | Neg | IgM = 0.1, IgG = 0.1, (neg) | 714 | 1.6 | 115 | 385 | 68/40 | 2 | - | 7 |

| Patient #17 | 13 | Girl | Respiratory distress, loss of consciousness | Peripheral ground glass patchy opacities due to COVID-19 | 17400 | 17 | 80 | 5.8 | 117000 | 40 | 88 | 6677 | 24 | 120 | 2.9 | Neg | 1.4 | Pos | - | 750 | 1.4 | 111 | 380 | 95/ 68 | - | - | 7 |

| Patient #18 | 8 | Boy | Fever, respiratory distress and focal seizure | Opacities suggestive for COVID-19 | 5600 | 7 | 90 | 13 | 115000 | 12 | 66 | 397 | 14 | 44 | 1.1 | Neg | 11 | Neg | - | 892 | 1.4 | 113 | 368 | 100/71 | - | - | 10 |

| Patient #19 | 0.5 | Girl | Fever, respiratory distress and cough | Bilateral peripheral ground glass opacities due to COVID-19 | 17000 | 23 | 61 | 10.4 | 465000 | 13 | 1 | 674 | 13 | 31 | 1 | Neg | 0.1 | Neg | - | 780 | 1.7 | 100 | 380 | 99/70 | - | - | 6 |

| Patient #20 | 4 | Girl | Febrile convulsion and respiratory distress | Opacities due to COVID-19 and aspiration pneumonia | 13000 | 12 | 84 | 10.6 | 209000 | 5 | 26 | 1036 | 13 | 39 | 1 | Neg | 0.03 | Neg | - | 763 | 1.4 | 97 | 376 | 89/68 | - | - | 10 |

| Patient #21 | 2 | Boy | Respiratory distress | Opacities due to COVID-19 | 15000 | 7 | 83 | 9.7 | 882000 | 25 | 58 | 634 | 13 | 46 | 1 | Neg | 0.1 | Neg | - | 840 | 1.4 | 120 | 380 | 85/67 | - | - | 11 |

| Patient #22 | 0.92 | Boy | Respiratory distress and seizure | Opacities due to COVID-19 | 16700 | 19 | 78 | 10 | 244000 | 9 | 67 | 396 | 13 | 27 | 1 | Neg | 0.2 | Neg | - | 778 | 1.5 | 119 | 389 | 70/49 | - | - | 5 |

Summary of Clinical Presentation of Patients

As seen, this study encompasses 22 pediatric patients with varied clinical presentations. Patients presented with symptoms such as seizures, abdominal pain, respiratory distress, fever, and shock, necessitating treatments including antibiotics, antivirals, immunoglobulins, and vasopressors. Mechanical ventilation was required for several patients due to respiratory compromise, and arrhythmias were observed in some cases. Despite the severity of the illness, the majority of patients were discharged in stable condition after receiving appropriate medical intervention. Unfortunately, one patient succumbed to the illness.

5. Discussion

In the current study, all 22 patients presented with a low systemic vascular resistance index. Six patients had low SVRI despite normal blood pressure. Systemic vascular resistance plays an important role in creating and regulating blood pressure (14). Clinical examination is a crucial tool for evaluating and treating critically ill patients with hemodynamic disorders. However, in complex cases, this assessment may be done incorrectly.

Echocardiography is an excellent tool for checking hemodynamic status and heart function, but it requires a cardiologist and is time-consuming. The USCOM device is very useful for accurate and quick assessment of hemodynamic status. It is also valuable for treatment follow-up and serial evaluation of patients (15). The USCOM device helped us assess the hemodynamics and response to the treatments performed in COVID-19 patients. With this device, we serially checked the hemodynamic parameters of the patients and adjusted the fluid therapy and inotropic drugs based on the results.

We found that the hypotension and decreased urine output of patients were secondary to the reduction of systemic vascular resistance. With the administration of norepinephrine, the patients' conditions stabilized well. The USCOM monitor plays an important role in intensive care monitoring. It is non-invasive, fast, accurate, affordable, safe, tolerable, and easy to learn to use. However, during the learning phase, USCOM measurements are somewhat operator-dependent. This device is suitable for use in cases of shock, dehydration, hypotension, and low cardiac output states.

In conclusion, this study presents detailed clinical and laboratory results of 22 children with COVID-19. Additionally, information related to their hemodynamic status was measured and presented using the USCOM device. While multiple studies have assessed COVID-19 characteristics, viral genetics, signs, symptoms, and complications, the use of USCOM in the evaluation and treatment of COVID-19 patients has not been reported until now. We recommend the use of the USCOM device for patient evaluation. It is hoped that this study will increase awareness of the specific subtype of shock associated with COVID-19 and its treatment. This information can provide physicians with a comprehensive understanding of the clinical history of patients presenting with COVID-19, thereby improving their knowledge and care delivery. However, this information is not sufficient to draw a final conclusion, and more studies are needed. We are currently using USCOM to evaluate other patients with hemodynamic disorders and will publish the results in the future.