1. Background

Gout is the most common chronic arthritic inflammatory disease, characterized by the deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals, primarily influenced by elevated serum uric acid (sUA) levels (1, 2). Research consistently shows that the risk of gout increases with higher sUA levels (3). The MSU crystals can form at physiological temperature and pH when urate concentrations exceed saturation levels (≥ 410 mmol/L, 6.8 mg/dL) (4). However, not all individuals with severe hyperuricemia develop acute inflammatory gouty arthritis, and the relationship between MSU crystal volume and uric acid concentration remains unclear (3).

Individuals with gout face heightened risks for various complications, including diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (5). A meta-analysis found that up to 24% of gout patients have stage 3 CKD or higher (6). Furthermore, gout is recognized as an independent risk factor for new-onset CKD (7). Declining glomerular filtration rate (GFR) may reduce uric acid excretion, thus promoting MSU crystal formation and complicating the relationship between kidney function and uric acid metabolism.

The MSU crystals predominantly deposit in the joints, with the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint being the most frequently affected site, followed by the Achilles tendon and ankle (8). The location of urate deposition may correlate with hematologic markers such as sUA and GFR, reflecting distinct pathophysiological processes.

Recently, dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) has emerged as a validated noninvasive method for detecting MSU deposits, demonstrating a sensitivity of 0.87 and specificity of 0.84 (9). The DECT utilizes two X-ray sources to simultaneously acquire spiral data, and a specialized algorithm processes these images to differentiate between MSU and non-MSU deposits, enhancing its value as a diagnostic tool for gout.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the correlations of different volumes of MSU crystals at the feet/ankles, knees, and hands/wrists on DECT with clinical characteristics such as sUA, GFR, and disease duration.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Participants and Related Factors

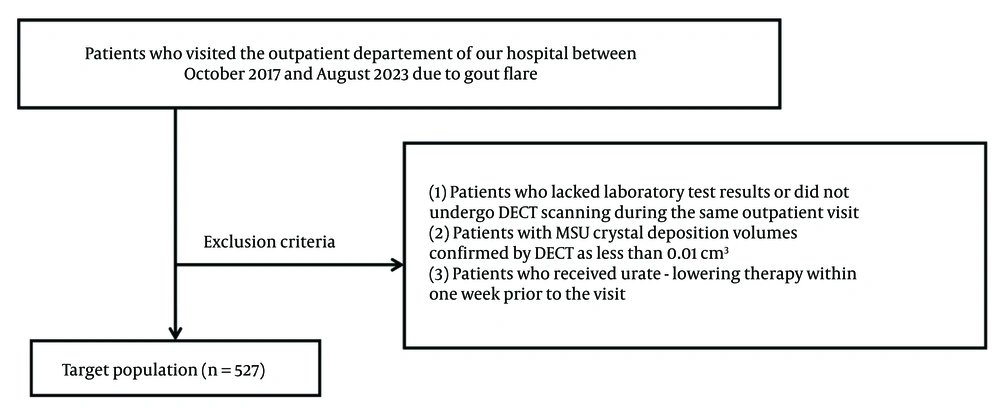

This study was conducted at a single center, where demographic and clinical data were extracted from electronic health records during outpatient visits. This retrospective cross-sectional study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital, and written informed consent was waived. We included patients presenting to the rheumatology outpatient department for gout flare between October 2017 and August 2023, based on the criteria displayed in Figure 1.

Demographic factors (age, gender) and clinical characteristics of gout (disease duration, number of tophi deposition sites, MSU crystal volume across joints, total volume, sUA, GFR) were analyzed. Disease duration refers to the period from the initial acute flare to the hospital visit. The GFR was calculated using the modified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation: c-aGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2) = 186 × Pcr-1.154 × age-0.203 × 0.742 (if female) × 1.227 (if Chinese) (10). The highest sUA and GFR values were analyzed per ACR/EULAR 2015 gout classification criteria (11).

A total of 527 patients were included, excluding those on urate-lowering therapy (ULT) within one week prior to the visit to prevent bias in sUA measurements, as well as patients with MSU volumes < 0.01 cm3, which may represent artifacts rather than actual urate deposits.

3.2. Grouping Definition

The American College of Rheumatology guidelines recommend maintaining sUA levels below 360 μmol/L (6 mg/dL) for patients on urate-lowering therapy (ULT) (8, 12). Studies have shown associations between sUA levels and various gout-related comorbidities (13). Research by Arthur Shiyovich et al. identified that serum urate levels ≥ 9.0 mg/dL in males are linked to adverse outcomes in diabetic patients (14). Therefore, sUA levels were categorized into three groups: ≥ 9.0 mg/dL, 6.0 - 9.0 mg/dL, and < 6.0 mg/dL.

According to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease, GFR was classified as ≥ 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 (normal/high) or < 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 (declined) (15). Additionally, we employed a volume threshold of 1 cm3 for MSU crystals, as established by Tristan Pascart et al., which identified factors such as gout duration, diabetes mellitus, and chronic heart failure as significantly associated with MSU volumes ≥ 1 cm3 (5). This threshold holds clinical significance and may provide predictive insights into gout attacks and related comorbidities.

3.3. Dual-Energy Computed Tomography Assessments

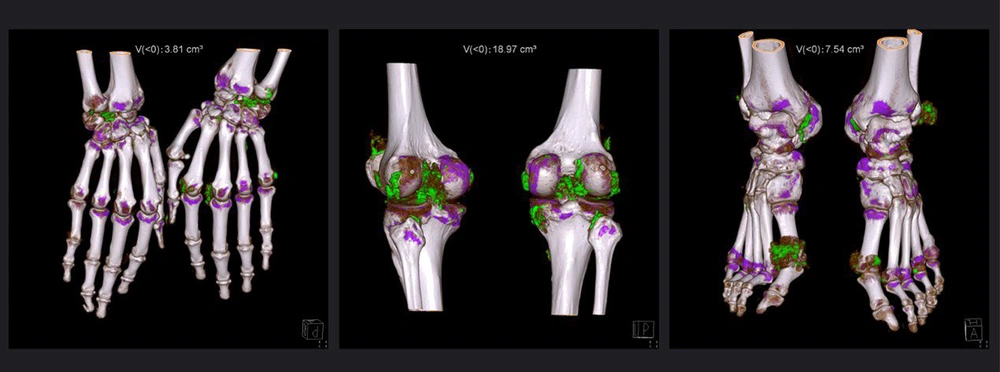

All subjects underwent DECT scans using a SOMATOM Definition Flash CT Scanner, scanning the feet/ankles, knees, and hands/wrists bilaterally. Tube A was operated at 140 kV/115 reference mAs with a 0.6 mm tin filter, while Tube B was operated at 80 kV/210 reference mAs. Detector collimation was set at 64 × 0.6 mm, and the rotation time was 1.0 second. The MSU deposits were visualized and color-coded using Syngo.via software (version VB 10B; Siemens Healthineers). Volume measurements were automated with the Syngo Dual Energy Gout software, excluding certain artifacts. The urate ratio was set to 1.36, and the smoothing range was set at 4. Fluid was set to a minimum of 150 Hounsfield units for the 80 kV/Sn140 kV images. Total MSU volume was calculated by summing measurements from each site (Figure 2).

Dual-energy CT reconstruction of bilateral wrists/hands, knees, and ankles/feet in a 54-year-old patient with a gout duration of 10 years. After excluding of nail bed, skin, and beam hardening artifacts, the numbers displayed on the top of the images indicated the volume quantification of monosodium urate crystal. Monosodium urate crystal deposition is color-coded as green.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, confirming a non-normal distribution of the data. Clinical characteristics were summarized using median and interquartile range (IQR). The Spearman correlation test was employed to evaluate associations between MSU crystal volume and sUA as well as GFR. All tests were two-tailed, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

4. Results

Patient demographics and characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Among 527 patients with positive DECT urate deposition, 497 were male, with a median age of 49.0 years and a median gout duration of 6.0 years. Monosodium urate crystals were predominantly deposited in the feet/ankles (84.8%), followed by the knees (63.6%) and hands/wrists (28.8%). The median MSU crystal volumes were larger in the knees (1.2 cm3) compared to the hands/wrists (0.5 cm3) and feet/ankles (0.8 cm3).

| Variables | Ankles/feet (n = 447, 84.8%) | Knees (n = 335, 63.6%) | Hands/wrists (n = 152, 28.8%) | Total (n = 527) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 49.0 (24.0) | 50.0 (23.0) | 51.0 (24.0) | 49.0 (23.0) |

| Male, No. (%) | 425 (95.1) | 318 (94.9) | 143 (94.1) | 497 (94.3) |

| Duration, y | 7.0 (6.0) | 8.0 (6.0) | 8.0 (5.0) | 6.0 (6.8) |

| Laboratory results | ||||

| GFR, mL/min | 95.9 (39.2) | 96.0 (45.4) | 88.0 (32.6) | 97.3 (42.1) |

| GFR ≥ 90 | 111.5 (28.6) | 115.5 (23.3) | 116.9 (24.4) | 111.9 (27.7) |

| GFR < 90 | 69.8 (26.2) | 30.0 (44.0) | 66.2 (15.3) | 69.7 (26.2) |

| sUA, mg/dL | 9.4 (3.2) | 9.4 (3.3) | 9.9 (3.6) | 9.4 (3.4) |

| sUA ≥ 9.0 | 10.6 (1.8) | 10.8 (2.0) | 11.0 (2.1) | 10.7 (1.9) |

| 9.0 > sUA ≥ 6.0 | 7.8 (1.2) | 7.9 (1.3) | 7.9 (0.6) | 7.7 (1.2) |

| sUA < 6.0 | 5.2 (1.0) | 5.2 (1.3) | 5.5(0.5) | 5.2 (1.2) |

| MSU, cm3 | 0.5 (3.9) | 1.2 (5.7) | 0.8 (4.1) | 15.6 (55.5) |

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics in Imaging Population a

The correlation between various clinical characteristics and MSU volumes is detailed in Tables 2 and 3. A significant correlation was observed between gout duration (categorized into two groups: ≥ 10 years and < 10 years) and MSU crystal volumes in the feet/ankles [r = 0.19 (95% CI: 0.015, 0.355), P = 0.02; r = 0.19 (95% CI: 0.061, 0.309), P < 0.01, respectively], knees [r = 0.20 (95% CI: -0.003, 0.388), P = 0.03; r = 0.20 (95% CI: 0.047, 0.349), P = 0.01, respectively], total volumes [r = 0.21 (95% CI: 0.052, 0.372), P < 0.01; r = 0.29 (95% CI: 0.173, 0.391), P < 0.01, respectively], and the number of MSU deposition regions [r = 0.25 (95% CI: 0.092, 0.406), P < 0.01; r = 0.32 (95% CI: 0.212, 0.424), P < 0.01, respectively].

| Variables | Ankles/feet (n = 447) | Knees (n = 335) | Hands/wrists (n = 152) | Total volumes (n = 527) | Number of MSU deposition regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sUA, mg/dL (n = 308) | 0.06 (0.52) | 0.06 (0.41) | -0.14 (0.17) | 0.08 (0.16) | 0.11 (0.07) |

| sUA ≥ 9.0 (n = 171) | 0.07 (0.38) | 0.04 (0.66) | -0.15 (0.24) | 0.05 (0.51) | 0.09 (0.22) |

| 9.0 > sUA ≥ 6.0 (n = 100) | -0.01 (0.94) | -0.03 (0.83) | 0.17 (0.41) | 0.06 (0.56) | 0.13 (0.21) |

| sUA < 6.0 (n = 37) | 0.18 (0.33) | -0.02 (0.92) | 0.09 (0.78) | 0.09 (0.59) | 0.22 (0.19) |

| Duration, y (n = 432) | 0.30 (< 0.01) b | 0.25 (< 0.01) b | 0.26 (< 0.01) b | 0.32 (< 0.01) b | 0.33 (< 0.01) b |

| Duration ≥ 10 (n = 161) | 0.19 (0.02) b | 0.20 (0.03) b | -0.14 (0.33) | 0.21 (< 0.01) b | 0.25 (< 0.01) b |

| Duration < 10 (n = 271) | 0.19 (< 0.01) b | 0.20 (0.01) b | 0.25 (0.03) b | 0.29 (< 0.01) b | 0.32 (< 0.01) b |

| GFR, mL/min (n = 273) | -0.18 (< 0.01) b | -0.16 (0.03) b | -0.06 (0.55) | -0.17 (< 0.01) b | -0.14 (0.02) b |

| GFR ≥ 90 (n = 163) | 0.01 (0.99) | -0.03 (0.72) | 0.03(0.87) | -0.02 (0.78) | -0.04 (0.64) |

| GFR < 90 (n = 110) | -0.13 (0.20) | -0.06 (0.63) | -0.06 (0.66) | -0.14 (0.15) | -0.15 (0.13) |

Association Between Clinical and Laboratory Parameters and Monosodium Urate Volume in Different Joints a

| Characteristics | MSU ≥ 1 cm3 (n = 241) | MSU < 1 cm3 (n = 285) | MSU volume at feet/ankles ≥ 1 cm3 (n = 184) | MSU volume at feet/ankles < 1 cm3 (n = 263) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sUA, mg/dL | -0.05 (0.55) | -0.04 (0.63) | 0.03 (0.72) | 0.06 (0.52) |

| sUA ≥ 9.0 | -0.02 (0.84) | -0.17 (0.13) | 0.05 (0.66) | -0.002 (0.98) |

| 9.0 > sUA ≥ 6.0 | -0.02 (0.89) | 0.06 (0.68) | 0.13 (0.40) | -0.04 (0.81) |

| sUA < 6.0 | 0.25 (0.42) | -0.28 (0.18) | 0.32 (0.29) | -0.31 (0.22) |

| Duration, y | 0.25 (< 0.01) b | 0.21 (< 0.01) b | 0.21 (0.01) b | 0.13 (0.049) b |

| Duration ≥ 10 | 0.18 (0.08) | -0.03 (0.82) | 0.15 (0.18) | -0.04 (0.76) |

| Duration < 10 | 0.22 (0.02) b | 0.21 (< 0.01) b | 0.27 (0.02) b | 0.04 (0.59) |

| GFR, mL/min | -0.25 (< 0.01) b | -0.04 (0.62) | -0.15 (0.12) | 0.01 (0.89) |

| GFR ≥ 90 | -0.01 (0.93) | -0.07 (0.56) | -0.006 (0.97) | -0.05 (0.64) |

| GFR < 90 | -0.08 (0.53) | 0.18 (0.22) | -0.01 (0.94) | 0.41 (< 0.01) b |

| Number of MSU deposition regions | 0.54 (< 0.01) b | 0.47 (< 0.01) b | 0.44 (< 0.01) b | 0.34 (< 0.01) b |

Association Between Monosodium Urate Volume and Clinical and Laboratory Parameters in Different Monosodium Urate Volume Groups

Regarding GFR, a significant correlation was found between GFR and MSU volume in the feet/ankles, knees, total MSU volume, and the number of MSU deposition regions [r = -0.18 (95% CI: -0.351, -0.072), P < 0.01; r = -0.17 (95% CI: -0.284, -0.052), P < 0.01; r = -0.14 (95% CI: -0.252, -0.013), P = 0.02, respectively]. However, no statistically significant correlation was observed between GFR and MSU volume in the hands/wrists [r = -0.06 (95% CI: -0.274, 0.142), P = 0.55]. Furthermore, no significant correlations were found when comparing the three GFR groups using cutoff values of 90 mL/min and 60 mL/min with MSU volume in the feet/ankles, knees, hands/wrists, total MSU volume, and the number of MSU deposition regions. Additionally, no statistically significant correlation was observed between MSU volumes and sUA levels across all groups.

Table 3 further supports the lack of significant correlations between sUA groups and MSU volume categories, consistent with the findings in Table 2. However, statistically significant correlations were observed between gout duration and the number of MSU deposition regions across the four MSU volume groups. The highest correlation coefficient was observed in cases where MSU crystal volume was ≥ 1 cm3 [r = 0.54 (95% CI: 0.443, 0.632), P < 0.01].

For patients with gout duration < 10 years, significant correlations were found between MSU volume and the four volume groups (except for MSU volume in the feet < 1 cm3), with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.20, reaching a maximum of 0.27 in the MSU volume at feet ≥ 1 cm3 group. Additionally, a significant negative correlation was identified between the MSU ≥ 1 cm3 group and total GFR [r = -0.25 (95% CI: -0.398, -0.099), P < 0.01].

5. Discussion

In this study, we identified a significant relationship between GFR and MSU crystal burden across various deposition sites, including the feet/ankles, knees, total MSU volumes, and the number of MSU deposition regions. Additionally, disease duration was significantly correlated with MSU volumes in different joints. However, no statistical association was observed between MSU volumes and sUA levels across the three defined ranges (≥ 9.0 mg/dL, 6.0 - 9.0 mg/dL, and < 6.0 mg/dL). These findings support our study's objective of examining the relationships between clinical characteristics and MSU burden.

Our analysis did not reveal a statistically significant correlation between total sUA levels or the three predefined sUA ranges and MSU volumes or deposition sites, which is consistent with the findings of Pascart et al. (5). This suggests that MSU deposition can occur even in individuals with hyperuricemia. Prior DECT studies have also reported weak correlations between MSU deposits and sUA levels (16). These results emphasize that sUA levels do not accurately reflect MSU burden in gout patients, reinforcing the notion that MSU crystal deposition is the central pathology rather than elevated sUA levels alone. Consequently, gout management strategies that rely solely on sUA monitoring may be inadequate. Our findings indicate that the presence of MSU deposits is not necessarily associated with persistently elevated sUA levels, suggesting that hyperuricemia is neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition for MSU crystal deposition.

Additionally, our study confirms that disease duration significantly influences MSU deposition, as demonstrated by a positive correlation between gout duration and MSU volumes in multiple joints. This aligns with Pascart et al.'s findings, which also reported a correlation between DECT-measured MSU crystal volumes and gout duration (5). We further observed a significant association between MSU volumes in the wrists/hands and disease duration, although this correlation weakened after 10 years. This suggests that MSU deposition in the wrists and hands may not increase linearly with disease progression, possibly due to delayed joint involvement and the effects of therapeutic interventions over time.

We propose that specific comorbidities contribute to MSU deposition independently of sUA levels. Normal sUA levels during gout flares may result from enhanced renal excretion. Gout and hyperuricemia are strongly associated with CKD, while CKD itself is an independent risk factor for gout (17). The MSU crystal deposition primarily arises from elevated urate concentrations due to impaired renal or gut excretion rather than urate overproduction. Our findings demonstrated a significant negative correlation between MSU volumes in the feet/ankles, knees, total MSU burden, and the number of MSU deposition regions with GFR. Previous studies have shown that patients with tophaceous gout exhibit lower GFR, suggesting that MSU deposition may serve as an indicator of renal function (18). Notably, we found a significant correlation between total MSU volume (≥ 1 cm3) and total GFR (Table 3). These findings suggest that regression of MSU crystals in the feet/ankles and knees, as well as a reduction in total MSU burden (≥ 1 cm3), during urate-lowering therapy (ULT) may lead to improved renal function and a reduced risk of CKD.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a single-center retrospective review with only 37 patients having sUA levels below 6.0 mg/dL, which may introduce selection bias. Additionally, incomplete treatment profiles and potential confounding factors, such as age, gender, and comorbidities, were not accounted for in the analysis. Future studies should incorporate these variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of MSU deposition and its clinical implications.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that MSU volumes correlate significantly with GFR levels but not with sUA levels. With the exception of MSU volumes in the hands/wrists for patients with over ten years of disease duration, MSU deposition in the feet/ankles, knees, total MSU burden, and number of deposition regions was associated with both disease duration and renal function in gout patients. Understanding these relationships can aid clinicians in predicting disease progression, optimizing urate-lowering therapies, and implementing early interventions to mitigate CKD risk.