1. Background

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), commonly known as concussion, is a prevalent condition, accounting for 70 - 90% of all treated brain injuries, with an incidence rate of approximately 100 - 300 cases per 100,000 people (1, 2). Despite being classified as "mild", mTBI can lead to various complications and long-term consequences, including neuropathological and neurocognitive changes (3, 4). Studies have demonstrated a correlation between iron accumulation and cognitive dysfunction in patients with chronic mTBI (5, 6). Longitudinal studies are ongoing to better understand the cascade of events that lead to iron accumulation in the brain following acute mTBI (7).

Accumulating evidence suggests that iron dysregulation and deposition play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of mTBI, contributing to oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, and cell injury, as well as disruption of the blood-brain barrier and subsequent neuronal damage (8). Iron is a micronutrient essential for various cellular functions, including energy metabolism, nucleic acid synthesis, and cell proliferation (9). However, excessive iron levels can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage cellular components such as lipids, proteins, and DNA (10, 11). This oxidative damage occurs because excess iron catalyzes the formation of hydroxyl radicals through reactions with hydrogen peroxide, a process known as Fenton’s chemistry (11). Additionally, ROS mediate ferroptosis, a newly recognized form of non-apoptotic cell death that occurs after TBI (12, 13). Studies have shown that iron accumulation in the brain, particularly in deep gray matter (DGM) regions, may contribute to the pathophysiology of mTBI-related cognitive impairments and post-traumatic headache, potentially serving as a biomarker for these conditions (14-16).

Advanced imaging techniques have played a crucial role in elucidating the role of iron in the pathophysiology of mTBI (17). These imaging modalities provide valuable insights into the distribution and impact of iron in the post-mTBI brain, aiding in the identification of potential therapeutic targets. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a powerful tool for diagnosing various medical conditions. Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) is an MRI technique that visualizes tissues with high magnetic susceptibility by combining magnitude and phase information to display variations in the tissue magnetic field (18). However, SWI is affected by regional field effects and image artifacts, which are influenced by imaging parameters (19-21). Although SWI has been used for diagnosing and monitoring conditions involving iron deposition, such as neurodegenerative diseases and neuromuscular disorders (22-24), its diagnostic performance is lower than that of quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM). Additionally, SWI provides only qualitative information regarding tissue magnetic susceptibility (25, 26).

The QSM is a post-processing technique that quantifies iron distribution in the brain and is superior to other techniques such as T2* and SWI (27). The QSM measures magnetic susceptibility using MRI phase and magnitude data. The relationship between magnetic susceptibility, as assessed by QSM, and iron accumulation in brain tissues has been previously reported (28). The QSM enables accurate mapping of iron deposition in various neurological conditions (29). The ability of QSM to precisely map iron deposition and other pathophysiological changes makes it a valuable tool for understanding mTBI and its associated complications, paving the way for improved diagnostic and management strategies.

2. Objectives

This study hypothesizes that mTBI is associated with increased iron deposition in the DGM nuclei, which can be measured using QSM, thereby providing new insights into mTBI pathophysiology.

Although previous studies have investigated changes in iron levels and magnetic susceptibility in different brain regions in both patients and animal models, few studies have examined iron alterations in mTBI patients using the QSM technique. The present study aimed to assess changes in magnetic susceptibility values in the DGM nuclei of individuals with mTBI using QSM.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Ethics Statement

The Research Ethics Committee of Baqiyatallah Hospital approved this study (ethical code: IR.BMSU.BAQ.REC.1402.032). All participants with potentially identifiable images or data provided written informed consent before inclusion in the study. Additionally, patients and healthcare providers were briefed on the study details and provided informed written consent before data collection.

3.2. Participants

The criteria for including mild TBI patients were based on the World Health Organization’s Collaborating Center for Neuro-Trauma Task Force guidelines (30). Patients were involved in motor vehicle accidents (MVA) or were pedestrians with confirmed head trauma and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13 - 15 upon arrival at the emergency department of Baqiyatallah Hospital. They exhibited specific symptoms such as loss of consciousness for less than 30 minutes and post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) for less than 24 hours. Magnetic resonance imaging imaging was conducted within 14 days of injury. Eligible patients were between 16 and 45 years old. To minimize the effect of age on iron deposition results, only individuals under 45 years old were included.

Exclusion criteria included a history of previous brain injuries, neurological diseases, psychiatric conditions, substance abuse, structural brain abnormalities, skull fractures, sedative use, and penetrating craniocerebral injuries.

In this study, we selected ten patients (age range: 25 - 45 years) with mTBI who presented to the National Brain Mapping Laboratory (NBML, Tehran, Iran) and were approximately 14 days post-injury at the time of MRI imaging. Additionally, we selected ten healthy subjects through purposive sampling. Participants were chosen based on inclusion (age, sex, handedness) and exclusion (history of trauma and psychiatric disorders) criteria. The healthy controls (HCs) were carefully matched to the mTBI patients in terms of age, sex, and handedness.

3.3. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Protocol

Magnetic resonance imaging images were acquired using a 3.0 Tesla scanner (Prisma, Siemens, Erlangen, München, Germany) equipped with a superconductive zero-helium boil-off 3T magnet at the NBML center and a 20-channel head and neck coil. A 3D T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (T1-MPRAGE) sequence was used to obtain high-resolution structural MRI data, consisting of 176 slices with no gap and a voxel resolution of 1 × 1 × 1 mm (TR = 1800 ms, TE = 2 ms, scan time = 4 min, voxel resolution = 1 × 1 × 1 mm, slice thickness = 1 mm, field of view (FOV) read = 255 mm, FOV phase = 100%).

Susceptibility-weighted imaging was performed using a 3D gradient-recalled echo (GRE) sequence with the following parameters: TR = 30 ms, TE1 = 6 ms, number of echoes = 5, flip angle = 15°, voxel resolution = 0.8 × 0.8 × 2 mm, and slices per slab = 72.

3.4. Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping Analysis

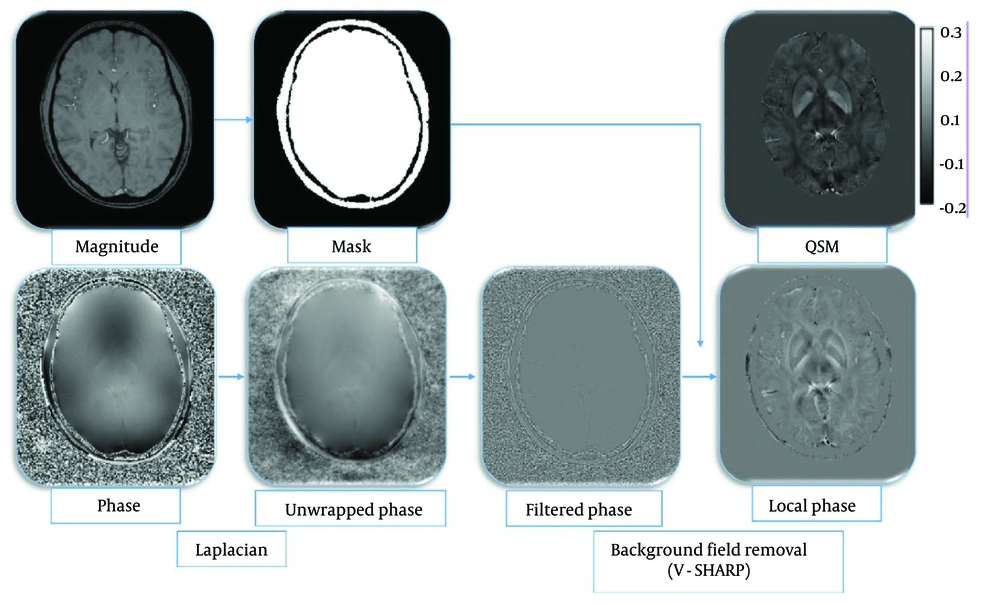

The QSM was reconstructed from SWI sequence data acquisition through a series of steps outlined in methodological studies: Phase unwrapping using the Laplacian-based method (31), background field removal employing the variable-kernel sophisticated harmonic artifact reduction for phase data (V-SHARP) method (32-34), and field-to-susceptibility inversion using the streaking artifact reduction for QSM (STAR-QSM) method (35) (Figure 1).

Illustration of the reconstruction process of the quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) imaging technique: Magnitude QSM imaging technique. Magnitude images were used for mask creation; magnitude images were utilized for mask creation. The phase images were first processed using the Laplacian unwrapping method, and then the filtered phase images were obtained. The local phase was obtained using the variable-kernel sophisticated harmonic artifact reduction for phase data (V-SHARP) method, and ultimately, susceptibility maps were achieved using the streaking artifact reduction for QSM (STAR-QSM) method.

The QSM calculations were conducted using MATLAB 2022b (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and the STI Suite, a MATLAB toolbox version 3.0 package (31). The resulting QSM images were analyzed to assess tissue magnetic susceptibility properties, including the presence of iron accumulation in the DGM nuclei.

Before segmentation, the QSM images were registered onto T1-weighted images using SPM 12 software. The T1-weighted images were then used for segmenting the DGM nuclei, including the thalamus, caudate nucleus, globus pallidus, putamen, amygdala, and hippocampus, using FSL software. The extracted masks were applied for the segmentation of the QSM images. Segmentation was performed to calculate magnetic susceptibility indices in the targeted regions.

3.5. Statistical Analyses

Assumptions of normality were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The significance level was set at α = 0.05. Group differences were analyzed using independent t-tests for normally distributed data and Mann-Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed data. To control for Type I error due to multiple comparisons across the 12 brain regions, a Bonferroni correction was applied, adjusting the significance threshold to P < 0.0041 (0.05/12). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16 (SPSS Inc. Released 2007. SPSS for Windows, Version 16.0. Chicago, SPSS Inc.).

4. Results

We collected data from 10 mTBI patients and 10 HCs. No significant differences were found between the mTBI and HC groups in terms of age, sex, or handedness (all participants were right-handed) (Table 1).

| Variables | mTBI (N = 10) | HC (N = 10) | P-value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 6 (60) | 6 (60) | 1.000 |

| Age (y) | 34.2 ± 10.8 | 31.6 ± 13.4 | 0.63 |

| Handedness (right) | 10 (100) | 10 (100) | 1.000 |

| DAI | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: mTBI, mild traumatic brain injury; HC, healthy control.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b P < 0.05 considered significant.

The results of the Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that, except for the left putamen variable, all other variables were not normally distributed (Table 2). The mean, standard deviation, mean difference, 95% confidence interval for the mean difference as an effect size, and P-value for comparing means between the two groups (mTBI patients and HCs) are presented in Table 3.

| Shapiro-Wilk test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Statistic | df | P-value |

| R_putamen | 0.514 | 20 | 0.000 |

| L_putamen | 0.948 | 20 | 0.341 |

| R_caudate | 0.855 | 20 | 007 |

| L_caudate | 0.765 | 20 | 0.000 |

| R_thalamus | 0.796 | 20 | 0.001 |

| L_thalamus | 0.624 | 20 | 0.000 |

| R_ globus pallidus | 0.700 | 20 | 0.000 |

| L_ globus pallidus | 0.770 | 20 | 0.000 |

| R_amygdala | 0.800 | 20 | 0.001 |

| L_amygdala | 0.874 | 20 | 0.014 |

| R_hippocumpus | 0.737 | 20 | 0.000 |

| L_hippocampus | 0.785 | 20 | 0.001 |

| Variables and groups | Mean ± SD | Mean difference | 95% Confidence interval of the difference | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| R_putamen | 0.002 | -0.0011 | 0.0069 | 0.06 | |

| Patient | 0.023 ± 0.006 | ||||

| Control | 0.020 ± 0.0008 | ||||

| L_putamen | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.0022 | 0.02 | |

| Patient | 0.020 ± 0.001 | ||||

| Control | 0.019 ± 0.0009 | ||||

| R_caudate | 0.004 | 0.0016 | 0.0068 | < 0.001 | |

| Patient | 0.029 ± 0.003 | ||||

| Control | 0.025 ± 0.001 | ||||

| L_caudate | 0.005 | 0.0016 | 0.0083 | 0.002 | |

| Patient | 0.030 ± 0.005 | ||||

| Control | 0.025 ± 0.0008 | ||||

| R_thalamus | 0.0009 | 0.0003 | 0.0015 | 0.004 | |

| Patient | 0.002 ± 0.0008 | ||||

| Control | 0.001 ± 0.0001 | ||||

| L_thalamus | 0.0009 | 0.00009 | 0.0018 | 0.05 | |

| Patient | 0.002 ± 0.001 | ||||

| Control | 0.001 ± 0.0001 | ||||

| R_ globus pallidus | 0.016 | 0.0042 | 0.0280 | 0.007 | |

| Patient | 0.046 ± 0.01 | ||||

| Control | 0.030 ± 0.001 | ||||

| L_ globus pallidus | 0.012 | 0.0040 | 0.0212 | 0.007 | |

| Patient | 0.043 ± 0.01 | ||||

| Control | 0.031 ± 0.001 | ||||

| R_amygdala | 0.001 | 0.0003 | 0.0030 | 0.06 | |

| Patient | 0.006 ± 0.002 | ||||

| Control | 0.004 ± 0.0004 | ||||

| L_amygdala | 0.001 | 0.0005 | 0.0026 | 0.02 | |

| Patient | 0.006 ± 0.001 | ||||

| Control | 0.005 ± 0.0005 | ||||

| R_hippocumpus | 0.001 | 0.0004 | 0.0025 | 0.002 | |

| Patient | 0.003 ± 0.001 | ||||

| Control | 0.002 ± 0.0003 | ||||

| L_hippocampus | 0.001 | 0.0003 | 0.0020 | 0.02 | |

| Patient | 0.003 ± 0.001 | ||||

| Control | 0.002 ± 0.0002 | ||||

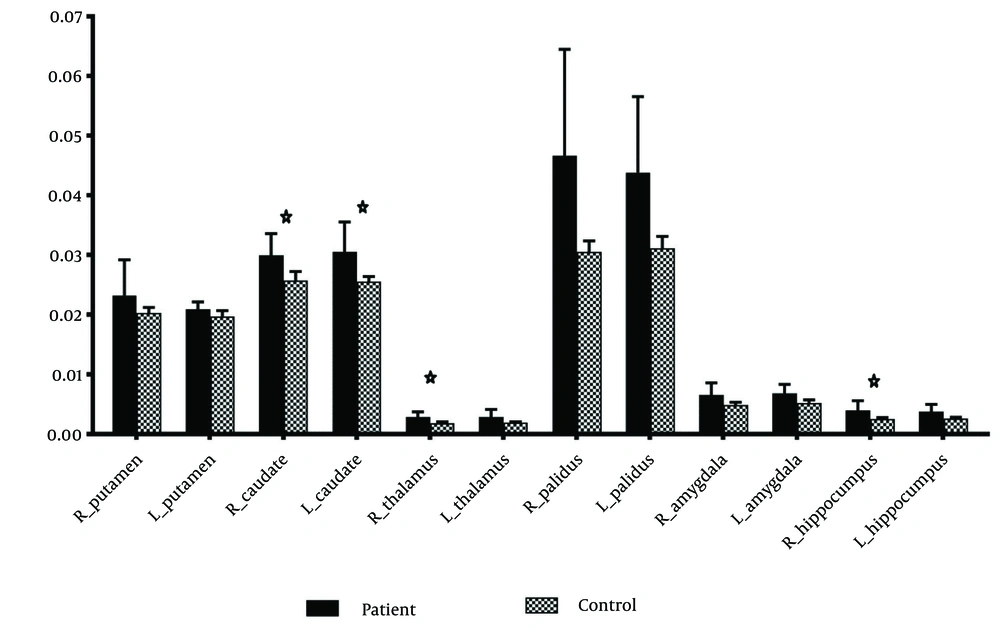

Significant differences in magnetic susceptibility were observed in the right caudate (P < 0.001), left caudate (P = 0.002), right thalamus (P = 0.004), and right hippocampus (P = 0.002) (Table 3 and Figure 2). The results for other regions, including the right putamen (P = 0.06), left putamen (P = 0.02), left thalamus (P = 0.005), right globus pallidus (P = 0.007), left globus pallidus (P = 0.007), right amygdala (P = 0.06), left amygdala (P = 0.02), and left hippocampus (P = 0.02), were not statistically significant.

The mean, standard deviation, mean difference and 95% confidence interval for mean difference as effect size and P-value for comparing means in two groups of patients and HCs. The significance level was P < 0.0041 (0.05/12).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate alterations in iron deposition (magnetic susceptibility) in the basal ganglia and thalamus of mTBI patients using the QSM technique. While white matter is also important in the context of brain injury, our primary focus on DGM was driven by the well-established involvement of these regions in cognitive and neurological impairments associated with mTBI.

Our findings revealed a notable increase in magnetic susceptibility values within the DGM nuclei regions in an average of ten patients. These changes were significant in the right and left caudate nuclei, right thalamus, and right hippocampus. These results suggest a potential link between mTBI and iron deposition in the brain, contributing to our understanding of the role of iron accumulation in mTBI pathophysiology.

The DGM nuclei house critical structures, such as the basal ganglia and thalamus, which play a vital role in motor control, cognition, executive functions, and emotional regulation (36). Higher iron deposition in the thalamus and hypothalamus has been correlated with poor memory performance, while higher iron levels in the caudate nucleus have been linked to cognitive decline (37). Iron is essential for various neurological functions, but excess iron can lead to oxidative stress and neurotoxicity (38), potentially contributing to mTBI symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive decline, and movement disorders (14, 15).

To understand the long-term pathogenesis resulting from TBI, Onyszchuk et al. subjected mice to controlled impact and performed MRI scans on their brains two months post-injury. The results revealed a decrease in T2 signal in the injured side of the thalamus, indicating increased iron levels in this region (39). The initial study examining iron accumulation in the DGM nuclei included 28 patients with mTBI. The results showed a significant increase in magnetic field correlation values within the thalamus and globus pallidus of mTBI patients, indicating iron accumulation. These findings support the idea that DGM nuclei are affected by mTBI and suggest a potential association between iron accumulation and pathophysiological processes following mTBI (7).

To confirm these post-injury changes, Liu et al. collected brain tissue samples from 19 patients undergoing surgical intervention for TBI 3 - 17 days after trauma. Tissue iron deposition and ferritin heavy chain expression were measured using tissue staining, polymerase chain reaction, western blot, and immunohistochemistry, showing an increase in ferritin chain expression and iron accumulation in the brain (40). In a study conducted six months post-injury using SWI phase images, an increase in the radian angle was observed in various brain regions, such as the thalamus, lenticular nucleus, hippocampus, substantia nigra, and red nucleus (5).

Several studies have also investigated changes in iron levels in the brain following injury using the QSM technique. Among these, Lin et al. reported changes in the thalamus 14 days after mTBI (41). Additionally, a recent study by Koch et al. on athletes two days after mTBI reported a general decrease in magnetic susceptibility values in the DGM regions (42). In contrast, some studies have indicated no significant changes in magnetic susceptibility values in the DGM regions of individuals with brain injury (43, 44).

An increase in magnetic susceptibility values in the DGM nuclei likely indicates iron deposition resulting from neuroinflammatory processes following mTBI. Trauma-induced disruption of the blood-brain barrier may facilitate iron accumulation in brain tissue, accompanied by oxidative stress and neuronal damage. This process creates a vicious cycle, where the generation of ROS and subsequent activation of microglia further contribute to iron dysregulation. Over time, these pathophysiological changes may lead to cell death, resulting in the long-term cognitive and motor impairments commonly observed in mTBI patients. Understanding these mechanisms in detail is crucial, as identifying them could lay the foundation for potential therapeutic interventions, such as iron chelation therapy, which may mitigate the effects of mTBI.

Our study had several limitations. The relatively small sample size necessitates further research to confirm these findings. Financial and time constraints, as well as limited access to participants, contributed to the small sample size. However, given this limitation, researchers prioritized data quality and measurement accuracy. Despite the small sample size, a significant difference was observed between the two groups. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge the impact of the limited sample size on the study’s ability to draw strong conclusions and its implications for the generalizability of the findings. The sample size was determined based on feasibility and the exploratory nature of the study. Additionally, longitudinal studies with larger cohorts are needed to track iron accumulation patterns over time and understand their association with mTBI recovery.

Further investigation is required to determine the precise timeline of iron accumulation following mTBI and its potential correlation with symptom severity and long-term outcomes. Additionally, exploring iron chelation therapy as a potential intervention for mTBI patients with iron overload is warranted.

In conclusion, our findings revealed iron deposition in the DGM nuclei of mTBI patients. These regions are integral components of cognitive networks, suggesting that alterations in iron levels may disrupt these circuits and contribute to the diverse clinical manifestations of mTBI, including neuropathological, neurophysiological, and neurocognitive changes. While replication in larger cohorts and longitudinal studies is necessary, these findings underscore the potential of quantitative neuroimaging biomarkers, such as QSM, to non-invasively characterize neural pathology involving iron in mTBI. Future research should further explore the role of iron in mTBI pathophysiology and investigate the potential for iron-targeted therapies to improve patient outcomes.