1. Introduction

Renal arteriovenous malformations (rAVMs) are defined as abnormalities wherein the artery and the vein communicate through a network of abnormal vessels (nidus) without interlaying capillaries. Renal arteriovenous fistula, defined as an abnormal direct communication between artery and vein is distinguished from rAVMs with the lack of a nidus. Two etiologies of rAVMs are described; congenital and acquired. Congenital rAVMs are extremely rare (1). The rAVMs may present with macrohematuria and renal colic, and they may be occasionally presented with fatal massive hematuria (2). They may be also asymptomatic. Doppler ultrasonography (USG), contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and angiography can be used for the diagnosis. An observational approach may be adopted in some asymptomatic rAVMs, whereas surgery or embolization should be considered in cases of hematuria, hypertension, or rupture. There are fewer reports on using Onyx for the treatment of rAVMs (3, 4). We successfully performed endovascular curative embolization with Onyx 18 in two patients of congenital and one patient of acquired rAVM.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Case 1

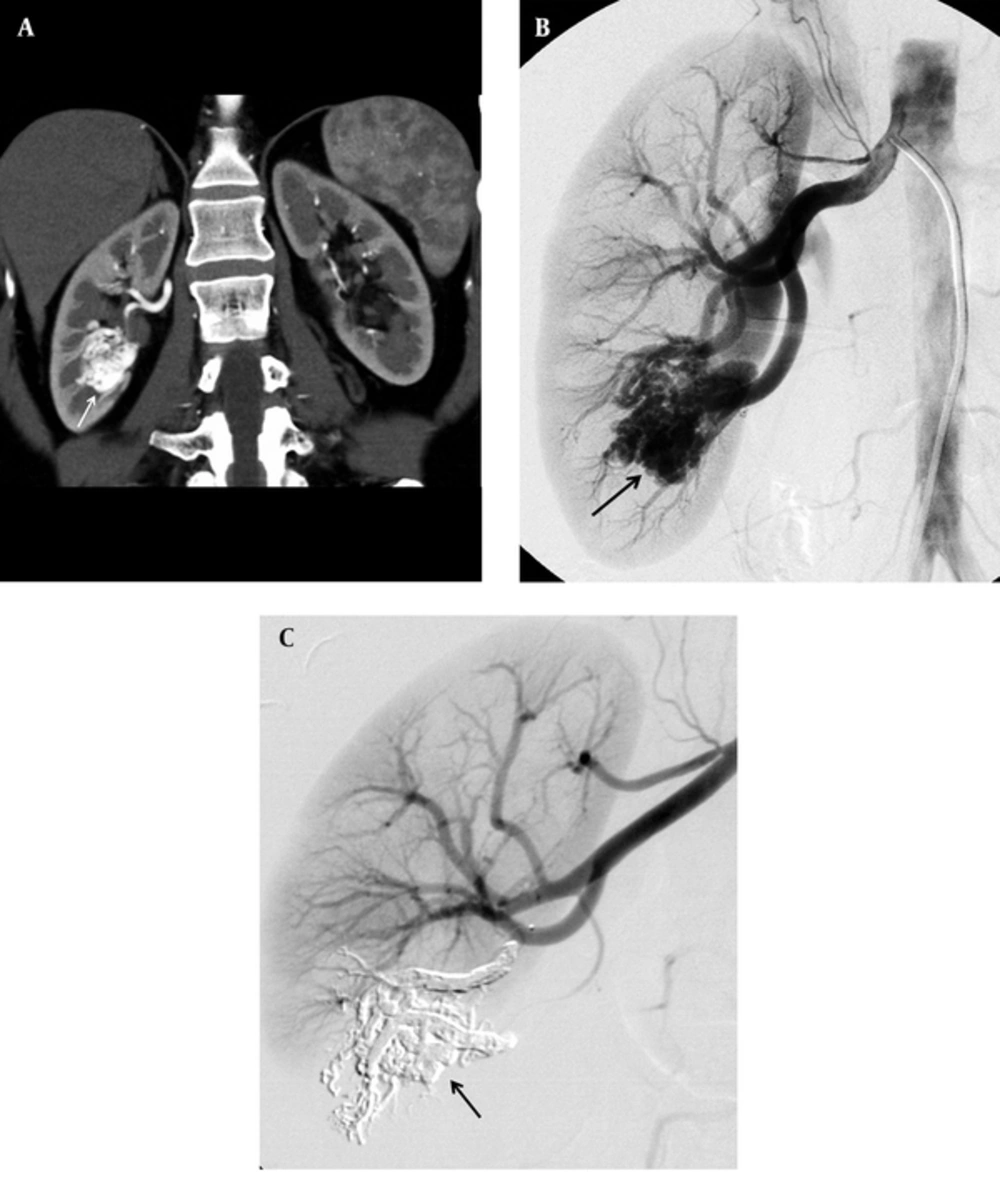

A 38-year-old woman was admitted to our institution with right-sided renal colic and microscopic hematuria. On USG, we did not see any finding including nephrolithiasis. On color Doppler USG, an intraparenchymal lesion of the right kidney with turbulent high flow was observed. Contrast-enhanced CT showed the cirsoid rAVM (Figure 1A). It was considered as a congenital rAVM, since there was no history of trauma. Selective renal angiography showed the glomerulus-like rAVM at the mid- to lower third of the kidney, located perihilar (Figure 1B). Endovascular treatment was performed under deep sedation. After puncture of the common femoral artery, a 6-F sheath was inserted, and a 6-F renal double curve guiding catheter (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) was placed from a right femoral access into the right renal artery. Then, superselective targeting of the renal interlobar artery feeding the AVM was performed using a detachable microcatheter (Sonic 1.5 F; Balt Extrusion, Montmorency, France). The microcatheter was manipulated over a 0.008 inch guidewire (Mirage; ev3 Inc., Plymouth, MN, USA) into the renal interlobar artery. Superselective embolization was performed by slow injection (0.1 - 0.2 mL/min) of 4.6 mL of Onyx 18 (ev3 Inc., Plymouth, MN, USA). Once the nidus of the rAVM filled, and the Onyx reached the draining vein, injection was stopped and the microcatheter was withdrawn. The total amount of Onyx used was high in this case, because the nidus of rAVM was fed from multiple arterial feeders. Control angiography showed the occlusion of the rAVM, which was filled by the radio-opaque Onyx. There was a small infarction area following the embolization without clinical consequences, and angiography revealed stable occlusion at the 12-month follow-up (Figure 1C).

38-year-old woman with right-sided renal colic, microscopic hematuria and intraparenchymal lesion with turbulent high flow in color Doppler ultrasonography. A, Coronal CT angiography reconstruction image of patient shows a congenital cirsoid arteriovenous malformation (arrow) of right kidney; B, Selective renal angiography image shows the arteriovenous malformation (arrow) at the mid- to lower third of the kidney; C, Angiography image shows stable occlusion (arrow) 12 months after treatment.

2.2. Case 2

A 36-year-old woman was admitted to our institution with massive hematuria. Before admission in our institution, she had received red blood cell transfusion of 6 units. Abdominal CT showed a ruptured rAVM of the right kidney, thrombus and hemorrhage in the dilated ureter. Selective renal angiography showed the cirsoid rAVM at the mid- to lower third of the kidney, located parapelvic. It was considered as a congenital rAVM, since there was no history of trauma. Superselective embolization was performed through a nondetachable microcatheter (Marathon; ev3 Inc., Plymouth, MN, USA) by slow injection of 2.4 mL of Onyx 18 under deep sedation. Control angiography showed total occlusion. The embolization results in a small infarction area without clinical consequences, and angiography at the 12-month follow-up revealed stable occlusion.

2.3. Case 3

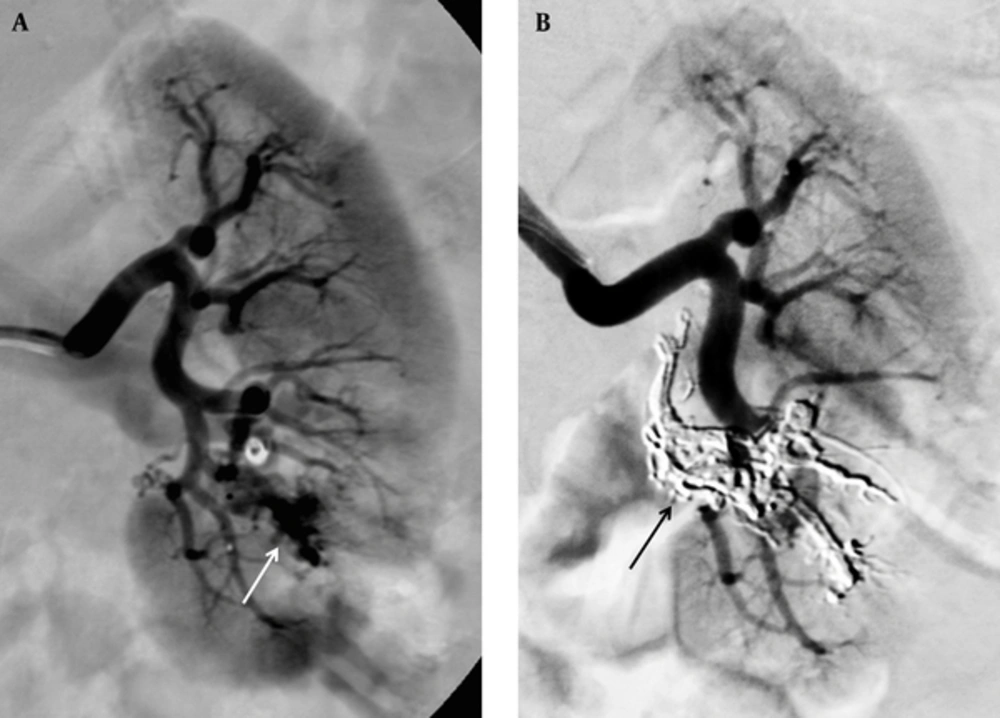

A 21-year-old woman was admitted to our institution with left-sided renal colic and hematuria. In her history, she had undergone renal biopsy of the left kidney 8 years ago, and a renal arteriovenous fistula complication had been occurred at early follow-up. The fistula had been occluded by a detachable balloon and coils. She has been under treatment for membranous glomerulonephritis disease over 8 years, and she has had attacks of left-sided renal colic with macroscopic hematuria lasting for 1 year. On color Doppler USG, a small intraparenchymatous lesion of the left kidney was observed. Selective renal angiography showed the acquired rAVM at the mid- to lower third of the kidney (Figure 2A). Superselective embolization was performed through a detachable microcatheter (Sonic 1.5F; Balt Extrusion, Montmorency, France) by slow injection of 1.2 mL of Onyx 18 under deep sedation. Control angiography showed the occlusion with a small infarction area (Figure 2B), and angiography at the 6-month follow-up revealed stable occlusion.

A 21-year-old woman with left-sided renal colic, hematuria and history of arteriovenous fistula after renal biopsy and its coil embolization. A, Selective renal angiography of patient shows an acquired arteriovenous malformation (arrow) at the mid- to lower third of the left kidney; B, Control angiography shows the occlusion (arrow).

3. Discussion

The reported prevalence of congenital rAVM is as low as 0.04%, but the true prevalence may be higher because of many asymptomatic rAVMs (1). The congenital ones represent a developmental abnormality that consists of multiple tortuous communications between arteries and veins without interlaying capillaries. The acquired ones usually result from iatrogenic causes (2). rAVMs can be either cavernous or cirsoid. A cavernous rAVM has a single arterial feeder, whereas a cirsoid rAVM is fed through multiple arterial feeders (2). Doppler USG, contrast-enhanced CT and angiography can be used for the diagnosis.

The treatment should be thought especially for the patients who have renal colic or large-sized rAVM and who are young and hypertensive. Surgical management, which is more invasive than endovascular embolization, is now reserved for cases related with malignancy and for cases, in which endovascular methods failed. In embolization with endovascular coaxial microcatheter-guidewire systems, the malformation can be assessed directly, and all arterial feeders can be evaluated and prepared for occlusion. The optimal course of treatment is geared toward eradication of the nidus and preservation of the normal renal parencyhma. rAVMs usually receive blood supply from two or more lobar vascular tributaries. In such cases, only permanent occlusion of all feeders and occlusion of the nidus would prevent the recurrence or residual rAVM. Superselective renal artery embolization commonly results in a small infarction of the nontarget renal parenchyma, which is usually not related with clinically significant reduction in function (5).

Liquid embolic materials such as Onyx (ethylene-vinyl alcohol copolymer) ensure curative embolization for the rAVMs. However, coils and the other mechanic embolic materials may not reach the nidus of the rAVMs as well as in brain AVMs, which may result in recurrence or residual AVM. Percutaneous endovascular embolic technique using a coil is limited by diameters of rAVM and multiplicity of vessel. In addition, coil migration is a potentially serious complication. Yoon et al. (6) reported an erosion complication (from kidney to descending colon) of the coils and guidewires that were used for the embolization of the rAVM. The mechanic embolic materials are effectively used for treatment of traumatic arteriovenous fistula as in our third case. That patient, whose rAVM was treated with Onyx, had underwent coil embolization for the traumatic arteriovenous fistula 8 years before the diagnosis of the rAVM. As a result, liquid embolic materials are preferred over coils for the treatment of rAVMs (5). Earlier reports on endovascular treatment of rAVMs describe embolization with liquid embolic materials, such as acrylic glue (n-butyl-cyano-acrylate, nBCA) or ethanol (7). The nBCA is cheaper than Onyx, but Onyx permitted long injection and embolization in a more controlled manner than nBCA (8). The nBCA, which does not penetrate deeply precipitates much more quickly than Onyx, and it may cause incomplete embolization of the AVM and glue precipitation in the microcatheter (8). Besides, the risk of migration to pulmonary vessels with nBCA is higher than that with Onyx, and we prevented migration of Onyx to pulmonary vessels with slow injection of Onyx. Additionally, one of the advantages of Onyx is that a single Onyx injection from one feeding artery can succeed in complete nidus occlusion, even though there were multiple feeding arteries. Thus, the nidus occlusion achieved by deep penetration of Onyx can block arterial inflow from other non-embolized feeding arteries, assuring curative embolization. Onyx 18 can penetrate deeper into the nidus due to its lower viscosity compared to Onyx 34.

Onyx has been investigated extensively for the treatment of intracranial arteriovenous malformations and fistulae (9). There have been few reports of use of Onyx for peripheral vascular malformations and bleeding, including rAVMs (3). Murata et al. (10) stated that clinical success rate was higher when a combination of coils and other agents or liquid agents were used, than when only coils were used. Rennert et al. (3) reported nine patients with several renal vascular lesions treated by the embolization with Onyx and rapid application of Onyx with a low complication rate. Wetter et al. (4) reported a case with a congenital rAVM, embolized successfully with Onyx. Different from this study, we had radiological follow-up in all of our patients. Besides, we used detachable microcatheters for superselective embolization in two of our cases unlike the other studies in the literature. We think that, the detachable microcatheters may be more advantageous than the nondetachable ones, because detachable catheters allow long injection and do not adhere to Onyx. When there are multiple feeders in a rAVM, detachable microcatheters may be more efficiently used than the nondetachable ones. We pointed out that detachable microcatheters, which were mainly used for the treatment of cerebral arteriovenous malformations can be also safely used for the treatment of rAVMs. Lastly, our third case is unusual with her presentation, as she had an acquired rAVM, occurred after 8 years following the occlusion of a traumatic renal arteriovenous fistula.

In conclusion, the rAVMs are rare, as is their embolization with Onyx. Endovascular curative embolization of the rAVMs with Onyx is a relatively new procedure. Our three patients with rAVM were successfully treated by the embolization with Onyx 18. The flow and precipitation patterns of Onyx reduce the risk of ischemic complications, and allow a safe embolization. As the nondetachable microcatheters, the detachable microcatheters may be also effectively used during the superselective embolizations of the rAVMs. Our follow-up showed good results of the embolizations with Onyx, indicating that this procedure can be commonly used.