1. Background

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) is a rare event, up to 8 per 1000 pregnancies (1). This term includes hydatidiform mole (HM) (either complete or partial) and malignant forms (persistent GTD), comprising invasive mole, choriocarcinoma and placental site trophoblastic tumor. Although HM is often treated with suction evacuation, about 15% of complete HM and 0.5% of partial HM transform into malignant forms (1-3). Serial assessment of serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) titers is a standard method to identify post molar malignancy. However, in the first weeks, β-hCG test has not the capability for early detection of high-risk patients. High-risk patients need a closer follow-up. It had been shown than prophylactic chemotherapy significantly decreases the rate of persistency in this group (4, 5). Transvaginal Ultrasonography is a noninvasive and inexpensive medical imaging tool used for diagnosis of various diseases. Using other imaging modalities, like computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography is limited for detection of metastasis or locoregional spread (1, 6, 7). MRI is useful for detecting myometrial invasion, but not performed routinely for the assessment of persistent disease. It is only indicated in difficult cases (1). Several studies were performed to evaluate the roles of multiple prognostic factors, as ultrasound gray scale, Doppler features, patient's history (as maternal age, gestational age, previous molar pregnancy and prolonged oral contraceptive use) and lab tests (6, 8-13). These factors are signs of high-risk state, particularly when coexist. Because of early detection of molar pregnancy with ultrasound, some of these features (as theca lutein cysts, larg uterine volume) are not encountered as common as previously.

2. Objectives

In this study, we examined several predictive factors of persistency, and mainly focus on ultrasound results during follow-up courses. Some ultrasound findings were determined to be effective in prediction and diagnosis of post evacuation malignancy as well as selecting high-risk patients.

3. Patients and Methods

During the study period (September 2009 to March 2011), 19 patients were included, and 130 sonographic exams were performed. Seventy-eight examinations were relevant to patients with spontaneous remission (from the least 4 to 10 exams) and 52 exams to patients with persistent GTD (from the least 4 to 10 exams). Informed consent was taken from each patient. All patients with molar pregnancy who did not perform evacuation before starting the study were included. In addition, histopathologic examination was performed for all patients after evacuation and any pathology other than molar pregnancy was excluded. Patients who did not perform their follow-up visits were excluded as well. This prospective study was approved by our institutional review board. Before evacuation, patient's history and laboratory data such as maternal age, gestational age, new hyperthyroidism and β-hCG titer were recorded. The radiologist was blinded to patient’s β-hCG titers, and all titers were checked in one biochemistry laboratory. All patients were evaluated with transvaginal ultrasound and data about uterine volume, ovarian theca lutein cysts and uterine artery Doppler indices were collected. Sonographic examination was performed by duplex ultrasound machine (Medison Accuvix V20 Prstige) using 7.5 MHz endovaginal probe. Uterine arteries adjacent to the cervix were examined. Sample volume size was set as 2 mm, and angle between the Doppler beam and the vessel was set as low as possible. Doppler indices, including systolic to diastolic ratio (S/D), resistive index (RI) and pulsatility index (PI) were calculated for each uterine artery by ultrasound machine software. At least two waveform samples in each side were obtained and the lowest value was used, then mean of both sides was measured as well. After evacuation, serum β-hCG titers were controlled weekly and follow-up ultrasound was performed in the following manner; one week after the evacuation, then every two weeks until 9th week and once a month, thereafter until sixth month. However, sometime patients with suspicious sonographic findings (as endometrial retained tissue, indistinct junctional zone and focal increased vascularity in the uterus) or abnormal β-hCG titer were followed weekly. Patients with rising or plateauing β-hCG titers was considered persistent, and before starting chemotherapy their follow-up program was stopped. Uterine artery Doppler indices, any obvious increased vascularity or abnormal echo in the endometrium or myometrium and any new changes in the follow-up exams were evaluated carefully. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software ver. 17 (SPSS Inc., 233 South Wacker Drive, 11th Floor, Chicago, IL 60606-6412). Paired t-test, chi-square test and mann whitney U test were performed. P-value less than 0.05 were considered significant.

4. Results

In this study, 19 patients were examined. Based on β-hCG titer during the follow-up course, patients were divided into two groups; patients experienced persistent GTD (group A), including eight (42%) patients and another group (group B), including 11 (58%) patients who had spontaneous remission. Mean follow-up assessments in group A was 6.5 and in the other group was seven. The first rise or plateauing of β-hCG in patients of group A occurred at the range of 2 to 10 weeks (mean: 4.56 ± 2.8 weeks).

4.1. Pre-Evacuation Data of Patients' History, Laboratory Tests and Ultrasonography

The mean value of maternal age in patients with persistent GTD of group A was 26.3 and the other group was 25 years. None of patients was older than 40 years as a risk factor of persistency. In addition, past history of molar pregnancy was not seen in any of patients. Eight (72.7%) patients with spontaneous remission and 6 (75%) patients in the other group had histologic confirmation of complete mole and other patients in the both groups had a partial mole. Data from patient history, β-hCG, and sonographic findings are depicted in Table 1. Only existence of a theca lutein cyst was statistically significant (P = 0.018). However, there were delicate points that should be noticed:

First, three of four patients, who had theca lutein cysts, had multiple bilateral cysts, and new hyperthyroidism and uterine volume ≥ 1000 cm3 were only seen in these patients. Another patient had a few unilateral cysts with normal thyroid function test and uterine volume < 1000 cm3. Second, only two patients of group B had new hyperthyroidism, which was very faint and only one of them had uterine volume ≥ 1000 cm3. Theca lutein cysts were not seen in any of them.

| Pre-Evacuation Findings | Spontaneous Remission | Persistent GTD | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian theca lutein cyst | 0 (0) | 4 (50) | 0.018 |

| Uterine volume, ≥ 1000 cm3 | 1 (9) | 3 (37.5) | 0.26 |

| Hyperthyroidismc | 2 (20) | 3 (42.9) | 0.59 |

| Gestational age, ≥ 12 weeks | 2 (18) | 4 (50) | 0.3 |

| Prolonged oral contraceptive use, > 1 year | 3 (27.3) | 3 (37.5) | 1 |

| Maternal age | 25 ± 6.2 | 26.3 ± 6.9 | 0.68 |

| Gestational age, week | 9.3 ± 2 | 10.1 ± 2.1 | 0.49 |

| β-hCG level | 137219.5 ± 177630 | 246512.8 ± 198012 | 0.15 |

| Uterine volume, cm3 | 417.9 ± 270.7 | 907 ± 638.5 | 0.25 |

aAbbreviations: GTD, gestational trophoblastic disease; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin.

bData are presented as No. (%) or Mean ± SD.

cPatients with spontaneous remission were 11 cases and patients with persistent GTD were 8 cases, but hyperthyroidism evaluated in 10 patients with spontaneous remission and 7 cases in another group.

4.2. Pulsed Doppler Study

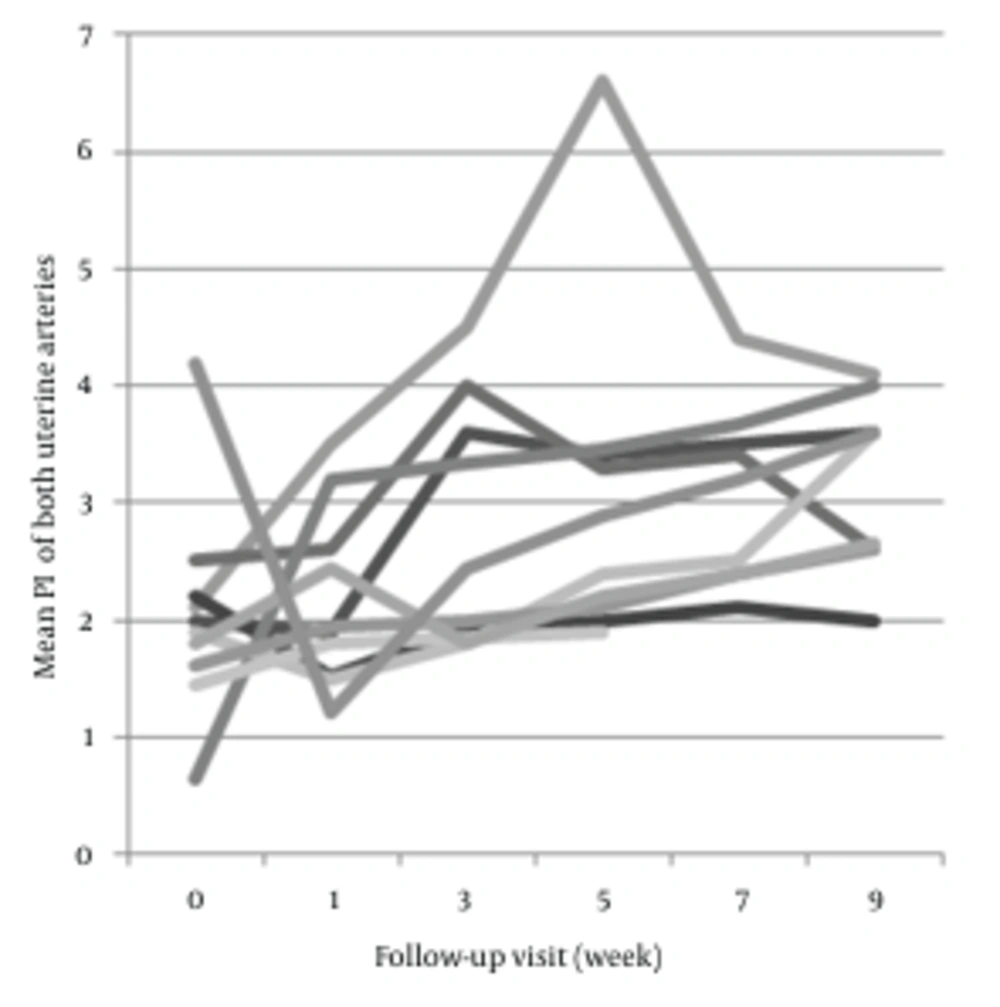

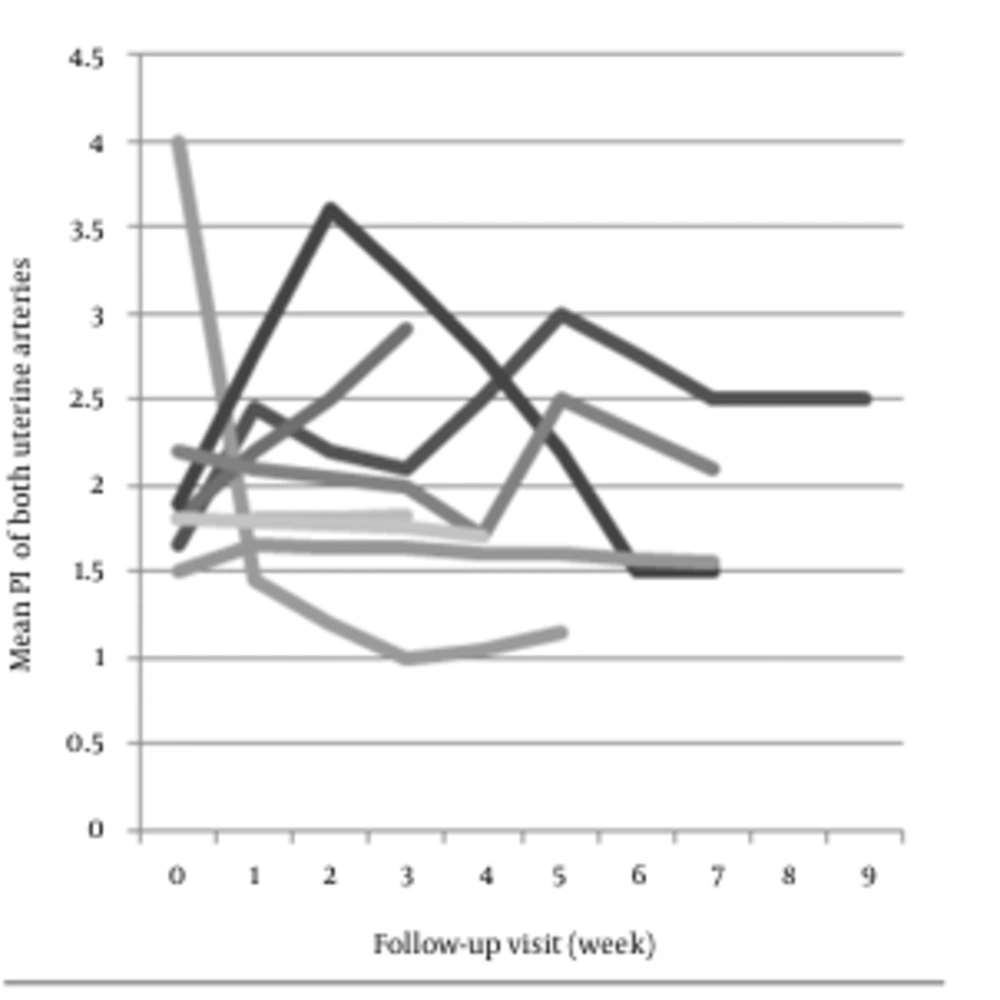

Findings of pulsed Doppler ultrasound from the both groups are presented in Table 2. In the group with spontaneous remission, Doppler indices (S/D, RI and PI) of uterine arteries showed a significant increase during 9 weeks follow-up course after evacuation (P = 0.02, P = 0.04 and P = 0.01, respectively) (Figure 1). In contrast, no significant changes were seen in patients of group B (P = 1, P = 0.6 and P = 0.7, respectively) (Figure 2).

| Spontaneous | Remission | P Value | Persistent GTD | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Evacuation | 9 Weeks After Evacuation | Before Evacuation | After β-hCG Rise or Plateauing | |||

| Uterine artery | ||||||

| S/D | 5.55 ± 2.61 | 25.8 ± 2.9 | 0.02 | 5.62 ± 2.55 | 4.8 ± 1.8 | 1 |

| RI | 0.76 ± 0.15 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.79 ± 0.1 | 0.76 ± 0.07 | 0.6 |

| PI | 1.95 ± 0.9 | 3.12 ± 0.79 | 0.01 | 2.12 ± 0.85 | 1.91 ± 0.57 | 0.7 |

| Myometrial vessel | ||||||

| S/D | 2 ± 0.28 | 2.4 ± 0.14 | 0.18 | 1.98 ± 0.73 | 1.85 ± 0.56 | 0.49 |

| RI | 0.48 ± 0.11 | 0.58 ± 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.46 ± 0.15 | 0.42 ± 0.12 | 0.39 |

| PI | 0.72 ± 0.17 | 1 ± 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.72 ± 0.37 | 0.62 ± 0.27 | 0.24 |

a Abbreviations: GTD, gestational trophoblastic disease; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; S/D, systolic to diastolic ratio; RI, resistive index; PI, pulsatility index.

b Data are presented as Mean ± SD.

Since the mean follow-up course in patients of group B was about 5.5 weeks, the data from another group in the 5th week was also analyzed to make a better comparison. Results indicated a significant increase in PI (P = 0.02). Besides, changes of RI and S/D were statistically significant (P = 0.06 and P = 0.09, respectively). Weekly changes in Doppler values were not significant in any of patients. Pre-evacuation Doppler indices of both groups were not significantly different (P = 0.56, P = 0.6 and P = 0.7, respectively). Hypervascularity of endometrium or myometrium, was seen in 2 (18%) patients of group B, and 7 (87.5%) of the other group. Although subtle rising in Doppler indices of patients of group B and mild decrease in the other group existed, these changes were not significant.

4.3. Post Evacuation Endometrial and Myometrial Ultrasound Findings

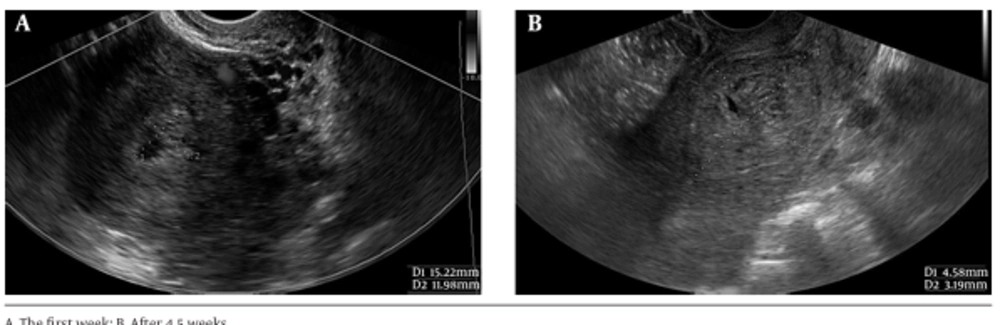

Eight (72.7%) patients of group B did not have any abnormality (as any retained tissue in the endometrium or any abnormal echo or focal hypervascularity in the myometrium) in the uterus on the first ultrasound exam or on other follow-up visits. In the other group, the first examination was normal in only one (12.5%) patient (P = 0.02), who had small polypoid lesions on the endometrial surface before β-hCG rise. In five (62%) patients of group A myometrial involvement, as a new nodule (in 2 patients) or a deep invasion (3 other patients) was observed in follow-up visits after evacuation; 2 patients had deep invasion in the first follow-up visit (their first β-hCG rise was detected at the second week of follow up visit in one patient and in fourth week of follow up visit in the other patient), Other three patients had new nodule or deep invasion at the same time of first rising of β-hCG titer (in two patients at seventh week and one patient at third week). In contrast, none of these myometrial findings were observed in group B. This difference was highly significant (P = 0.005). Focal indistinct junctional zone solely, without deep invasion into myometrium, was seen in two (18%) patients with spontaneous remission, and in two (25%) patients of the other group. One patient of group A had a retained tissue, which became progressively enlarged and hypervascular during the follow-up (from 15.2 × 12 mm in the first week to 45.8 × 31.9 mm in 5.5th week); Figure 3.

5. Discussion

According to FIGO, the sequential rise (more than 10%) of β-hCG for ≥ 2 weeks or plateauing (changes less than ± 10%) for ≥ 3 weeks are indications for starting chemotherapy (13). Although serum β-hCG titer is a powerful test and not yet replaced by other modalities, complementary method is needed:

Since either the entire or the maximum of tumoral tissue is evacuated, the first post evacuation titer of β-hCG usually reveals a decreasing trend. Thus, β-hCG rise or plateauing needs more than one titer (14) and, in turn, it cannot be helpful in early detection of high risk patients. For example, mean time of β-hCG rise in this study was 4.5 weeks.

Sometime its titers are not available at the time of ultrasound exam, and isolated sonographic criteria are helpful (12).

Several consecutive titers are needed to detect persistent disease and in high-risk patients when β-hCG titer is unavailable, can lead to a delay in diagnosis that increases patient's risk score and morbidity. Despite controversy, investigations indicated that prophylactic chemotherapy reduces the incidence of persistent disease in high-risk patients in this state and are useful (from 50% to 10-15%). However, chemoprophylaxis does not obviate the need for β-hCG follow-up courses (4, 5).

Several studies were performed on different predictive factors till now (9, 12, 13, 15). In this article, among different pre-evacuation factors, the theca lutein cyst is found to be a useful parameter. Its close association with new hyperthyroidism and uterine volume ≥ 1000 cm³ emphasizes that if a patient with GTD had new hyperthyroidism, multiple bilateral theca lutein cysts and large uterine volume, is very high-risk for further development of malignancy. However, in some previous studies it was shown that other factors had an association with persistent GTD (1, 16-18). In a study on 189 patients with GTD, only uterine size was significant among pre-evacuation factors (maternal age, gestational age, blood group, vaginal bleeding, uterine volume, theca lutein cysts) (13). Our limited number of patients could be a reason for this difference. In addition, the early detection of molar pregnancy by ultrasound may be another reason, we did not see these features as common as previous exams. In an evaluation of Doppler characteristics of the uterine arteries, we observed that the Doppler index values significantly increased in patients of group B during the follow-up, but did not in another group. Other studies revealed similar findings that changes in Doppler indices inversely correlated with β-hCG titers (8-10, 19). However, P value of these changes during 9 weeks follow-up course was not as significant as another similar investigation performed by Abd El Aal et al. (8). In their study, P value of Doppler index changes in each visit was about 0.0005. Nevertheless, in this study, weekly changes in Doppler values were not significant in any of patients. There was no significant difference in pre-evacuation Doppler results of the both groups. Although, changes were faint and occasionally unpredictable in each follow-up exam. As it is shown in Figures 1 and 2, weekly changes at least for a short period did not obey the usual rule, for example in some patients of group B (as shown in Figure 1), after rising Doppler values for weeks, sudden decline occurred and so on in group A (as shown in Figure 2). Therefore, it can be suggested that Doppler study is not a practical prognostic factor to differentiate these two groups. In this study, any abnormal finding in the uterus at the first follow-up examination was more related with persistent mole; in 7 (87.5%) patients of group A versus 3 (27.3%) patients of the other group (p = 0.02). Any abnormal echo in the myometrium or retained tissue in the endometrium at the first follow-up examination is predictive of a high-risk state. On the other hand, pre-evacuation prognostic factors are not observed as common as previously. Therefore, ultrasound, which can accurately diagnose high-risk patients in the first week, when β-hCG test is not helpful, has a worthful role in selecting patients who need closer follow-up. Focal indistinct junctional zone with hypervascularity in this area was observed nearly similar in the both groups, and did not increase the risk of persistent disease. The most statistically significant ultrasound findings in this examination were myometrial involvement as deeply invasion to myometrium and new myometrial nodule (P = 0.005). These findings were observed in two patients in the first follow-up (before rising of β-hCG titer) and in other three patients at the first rising of β-hCG titer. This confirms the recent investigations. In the study of Garavaglia et al. at multivariate analysis, only endometrial and myometrial involvement among different prognostic factors (maternal and gestational age, uterine size, theca lutein cyst, etc.) was significant (P = 0.0001) (13). Betel et al. compared GTD with retained product of conception. In this study, myometrial epicenter, deep invasion to myometrium, thin endometrium, placental sinusoids and large mass were their five significant sonographic criteria. No Doppler indices or theca lutein cysts were significant (12). Rapid growth of endometrial retained tissue was observed in one patient with persistent disease. Although it was not statistically significant, it is not considered a usual finding and suggests persistent disease. Many patients with GTD are from low socioeconomic class and do not follow perfectly their post evacuation β-hCG tests. Thus, in high-risk patients who do not perform β-hCG test at all or consecutively, observation of myometrial involvement or rapid growth of uterus mass is helpful to make a decision regarding the start of chemoprophylaxis. Despite the small sample size, several factors were evaluated in this prospective study in a serial manner and our follow-up examinations started at the first post evacuation week. However, in our review of literature, the most investigations on GTD were either retrospective or started several weeks after evacuation and none of them emphasized the role of first week ultrasound. This research indicated that in patients with GTD showing no pre-evacuation prognostic factors, first week ultrasound could detect high-risk patients. When β-hCG titer is not available in high-risk patients, ultrasound is an effective and useful method to make a decision of starting prophylactic chemotherapy and can be relied on as a powerful adjuvant to serum β-hCG test.