1. Background

Neuroendocrine tumors are defined as epithelial neoplasms with predominant neuroendocrine differentiation. They arise from Kulchitsky enterochromaffin cells and stain for chromogranin A and synaptophysin. Primary neuroendocrine tumors occur predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and lungs (1). The recent world health organization (WHO) classification in 2010 divided neuroendocrine tumors into three categories that could be applied to all sites within the gastrointestinal tract: grade 1 neuroendocrine neoplasm (low grade), grade 2 neuroendocrine neoplasm (intermediate grade), grade 3 neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), small cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma (high grade). The proposed grading has three tiers based on proliferation (G1, G2, and G3), with the following definitions of mitotic count and Ki67 index: G1: mitotic count < 2 per 10 high power fields (HPF) or < 3% Ki67 index; G2: mitotic count 2-20 per 10 HPF or 3% - 20% Ki67 index; and G3: mitotic count > 20 per 10 HPF or > 20% Ki67 index (2).

Gastric neuroendocrine tumors are classified on the basis of their differentiation status as well differentiated or poorly differentiated NECs (3). Well-differentiated (low and intermediate grade) neuroendocrine tumors have been variably termed carcinoid tumors (typical and atypical) and neuroendocrine tumors (grade 1 and grade 2). Poorly differentiated NECs (grade 3) of the stomach have been subdivided into small cell and large cell variants based on morphological characteristics (4-6). Most poorly differentiated NECs, including small cell and large cell variants, are diagnosed at an advanced stage and grow aggressively; half of the patients die of the disease within 12 months of diagnosis (7-9). Gastric endocrine tumors are observed increasingly often and as poorly differentiated NECs in the stomach with a poor prognosis, they demand an aggressive surgical approach combined with chemotherapy and radiotherapy (7). Therefore, it is important to consider the possibility of gastric NECs in the preoperative computed tomography (CT) evaluation of gastric carcinoma.

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one report of four cases of large cell NEC of the stomach (10), one report of three cases of small cell NEC (11), and one pictorial article about NEC of the gastrointestinal tract, including the stomach (12) in the English radiology literature. Our study involves a relatively large number of cases of gastric NECs compared to previous studies that analyzed a small number of cases. The purpose of our study is to describe the CT findings of gastric NECs with pathologic features.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients

The institutional review board approved this retrospective study, and informed consent was not required. We retrospectively reviewed the preoperative CT scan images of 32 patients (32 cases) with pathologically proven NEC of the stomach from January 2004 to January 2015. The pathologic diagnosis was confirmed using gastrectomy (n = 28) and endoscopic biopsy (n = 4).

The ages of the patients ranged from 45 to 79 years (mean: 62 years). Twenty-seven patients (84%) were men and five (16%) were women.

2.2. CT Technique

Because our study was retrospective, it included a variety of imaging techniques. Nineteen patients underwent 16-slice multidetector CT (MDCT) scanning (Sensation 16, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with 1000 mL of water to distend the stomach because wall thickening can be simulated by underdistention. Thirteen patients underwent helical CT scanning (Somatom plus S 40B, Siemens). The MDCT study was performed using the following parameters: 120 kV, 140 mA, and a 0.75 mm beam collimation at a 10 mm/rotation table speed. Helical CT was performed with a single 20 to 25 seconds breath-hold. A nonionic contrast agent (Ultravist 370, Bayer, Berlin, Germany) was injected intravenously at 3 cc/s. Fixed time delays were 70 s for the portal and 180 s for the equilibrium phase. The images were obtained in the craniocaudal direction and covered the area from the hepatic dome to the renal hilum. Follow-up CT was performed in all 32 patients at intervals of 1 - 6 months (mean: 3 months) after the initial CT.

2.3. Image Analysis

All CT images were retrospectively analyzed by two abdominal radiologists (20 and 13 years of specialty experience, respectively) with consensus for the morphology, size, and attenuation of the gastric tumor, as well as perigastric fat infiltration, lymphadenopathy, distant metastasis, and peritoneal carcinomatosis. The radiologists were blinded to the pathologic findings. All CT images were evaluated using a 2,000 × 2,000 picture archiving communication system monitor with adjustment of the optimal window setting in each case.

Gastric NECs were classified morphologically as polypoid (polypoid carcinomas, usually attached on a wide base), ulcerofungating (ulcerated carcinomas with sharply demarcated and raised margins), or ulceroinfiltrative types (ulcerated, infiltrating carcinomas without definite limits). The tumor size was regarded as the maximum diameter of the tumor and was divided into three ranges: less than 5 cm, larger than 5 but less than 10 cm, and larger than 10 cm. Low attenuation on CT scans was defined more than fat density and less than muscle density. Focal or diffuse low attenuation lesions within the gastric NECs and enlarged lymph nodes with internal low attenuation were evaluated.

2.4. Pathologic Analysis

A pathologist with 15 years of specialty experience retrospectively reviewed the pathologic findings of 32 patients with gastric NEC using immunohistochemical staining, and made diagnoses according to the 2010 WHO classification.

The pathologist was aware of the patients’ final diagnosis and the presence of low attenuation within the tumor or enlarged lymph nodes of gastric NEC on CT; the pathologist correlated the pathologic specimen findings with those of the CT scan with the assistance of a radiologist. Evaluation of low attenuation within the tumor was possible in 13 cases and low attenuation lymph nodes were identified in 10 cases.

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes the CT findings of gastric NECs in 32 patients.

| Small Cell NEC (n = 10) | Large Cell NEC (n = 22) | Total NEC (n = 32) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology | |||

| Ulcerofungating | 7 (70%) | 13 (59%) | 20 (63%) |

| Ulceroinfiltrative | 3 (30%) | 9 (41%) | 12 (37%) |

| Polypoid | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Size (cm) | |||

| 1 - 5 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 5 - 10 | 9 (90%) | 20 (91%) | 29 (91%) |

| > 10 | 1 (10%) | 2 (9%) | 3 (9%) |

| Low attenuation within mass | 5 (50%) | 13 (59%) | 18 (56%) |

| Low attenuation lymph nodes | 4 (40%) | 9 (41%) | 13 (41%) |

| Peritumoral infiltration | 0 (0%) | 2 (9%) | 2 (6%) |

| Liver metastasis (initial / follow up) | 2 (20%) /1 (10%) | 4 (18%) /2 (9%) | 6 (19%) /3 (9%) |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | 1 (10%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (6%) |

CT Findings of Gastric Neuroendocrine Carcinoma in 32 Patientsa

3.1. CT Findings

Among the three CT morphologic types (polypoid, ulcerofungating, and ulceroinfiltrative), 63% of the gastric NECs were ulcerofungating (n = 20), 37% were ulceroinfiltrative, and none were polypoid. Seven (70%) small cell NECs and 13 (59%) large cell NECs were ulcerofungating in appearance. All were larger than 5 cm in the greatest (mean size: 7.8 cm). There were 18 (56%) focal or diffuse low attenuations within the masses. Five (50%) small cell NECs and 13 (59%) large cell NECs showed low attenuation within the masses. Metastatic lymph nodes also showed similar low attenuation to the primary gastric tumor. Extensive low attenuation lymph nodes were observed in 13 (41%) patients. Four (40%) of these patients had small cell NECs and 9 (41%) had large cell NECs. Peritumoral infiltration was observed only in two (6%) large cell NECs. Initial preoperative CT scanning showed liver metastasis in six (19%) patients. Two (20%) of these patients had small cell NECs and four (18%) had large cell NECs. Follow-up CT scans obtained 1 - 6 months after surgery and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy showed liver metastasis in three (9%) patients. One (10%) of these patients had small cell NECs and two (9%) had large cell NECs. Peritoneal carcinomatosis was present in two (6%) patients. One patient had small cell NEC and the other had large cell NEC.

There were no significant differences between the small cell NEC group and the large cell NEC group in terms of tumor morphology, tumor size, low attenuation within the mass, low attenuation in the lymph nodes, peritumoral infiltration, hepatic metastasis, or peritoneal carcinomatosis.

3.2. Pathologic Findings

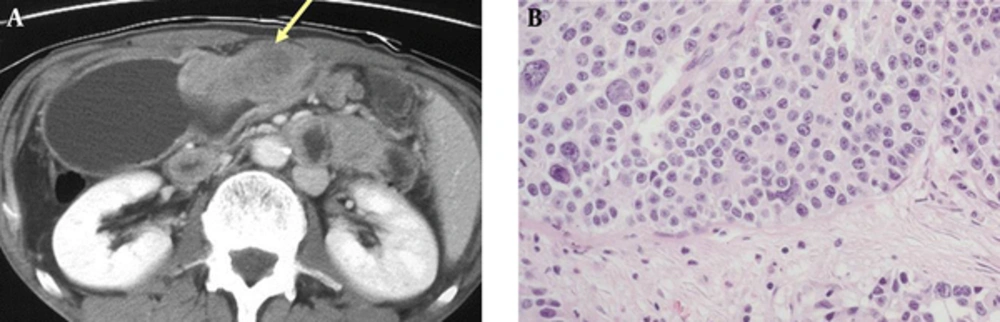

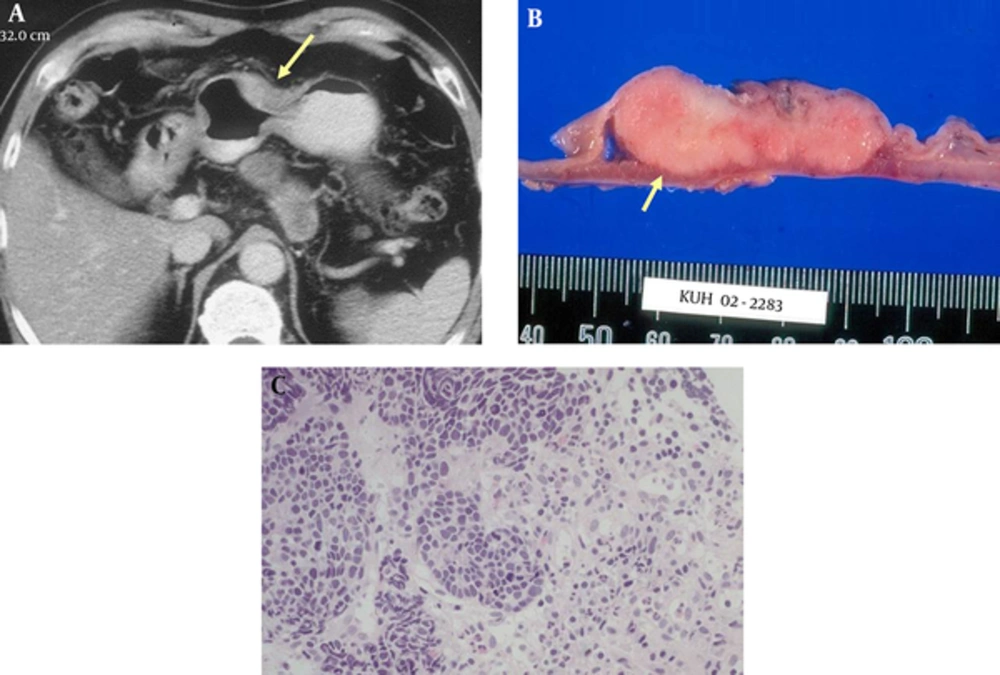

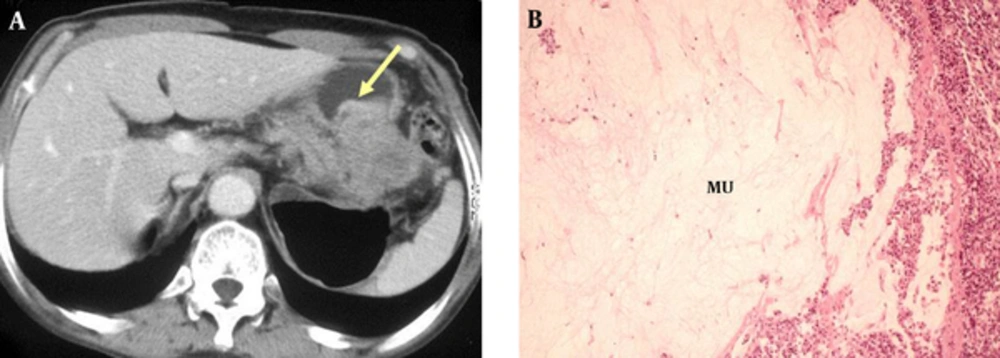

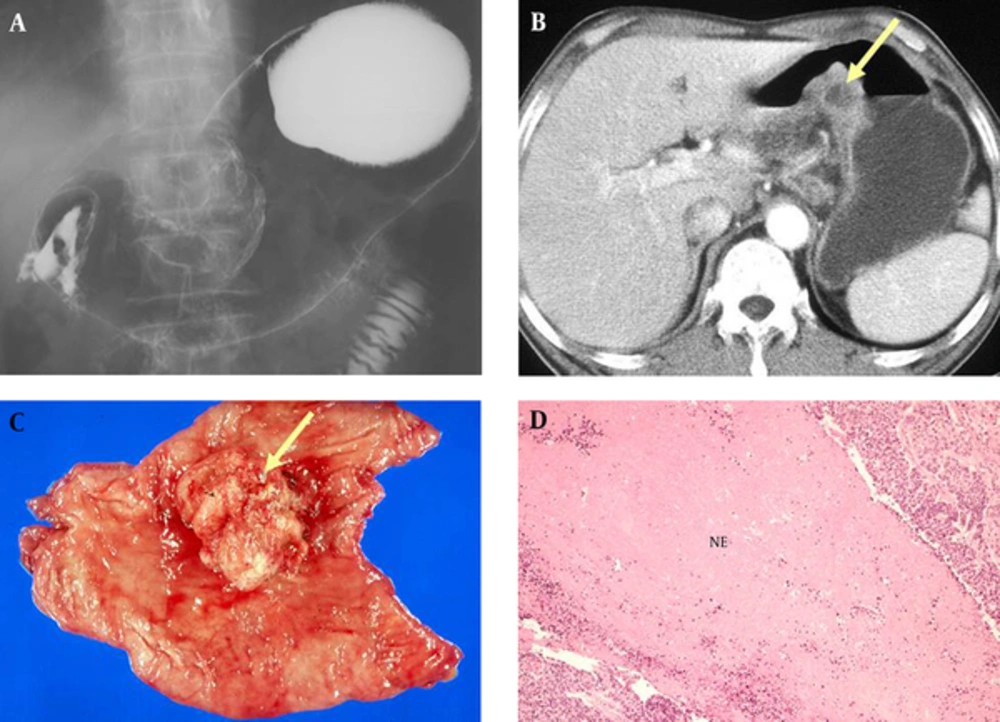

Pathologically, 22 patients were diagnosed with large cell gastric NECs (Figure 1) and 10 with small cell gastric NECs (Figure 2). Focal or diffuse low attenuation within gastric NECs was pathologically confirmed as mucin pools in five patients (Figure 3) or as massive necrosis in eight patients (Figure 4). Metastatic lymph nodes with internal low attenuation in all 10 patients were confirmed as necrotic (Figure 5).

A 59-year-old man with large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma in the gastric antrum and body. A, Equilibrium phase CT scan shows an ulcerofungating mass (arrow) in the gastric body with moderate heterogeneous enhancement. B, Photomicrograph of a histopathologic section shows large polygonal tumor cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, coarsely granular chromatin, and prominent nucleoli (H & E, x 100).

A 77-year-old man with small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma in the gastric antrum. A, Equilibrium phase CT scan shows an ulceroinfiltrative mass (arrow) with perigastric fat infiltration. B, Cut surface shows a well-demarcated solid pinkish tumor with extension to the muscle proper (arrow). C, Histopathologic section shows small tumor cells with scant cytoplasm and finely granular homogeneous chromatin without nucleoli (H & E, x 100).

A 79-year-old man with neuroendocrine carcinoma in the gastric body. A, Equilibrium phase CT scan shows an ulcerofungating mass, particularly in the low-attenuating outer layer. The thickening of the high-attenuating inner layer (arrow) is irregular. B, Photomicrograph of histopathologic section shows large mucin pools (Mu) mainly in the submucosal and proper muscle layers (H & E, x 100).

A 67-year-old man with neuroendocrine carcinoma. A, Double contrast upper gastrointestinal study shows a large irregular ulcerofungating mass in the lesser curvature of gastric angle. B, Early phase CT shows a polypoid mass with internal low attenuation (arrow). C, Resected specimen shows a large polypoid tumor with surface ulceration (arrow). D, Histopathologic section shows extensive tumoral necrosis (NE), mainly in the submucosal and proper muscle layers (H & E, x 100).

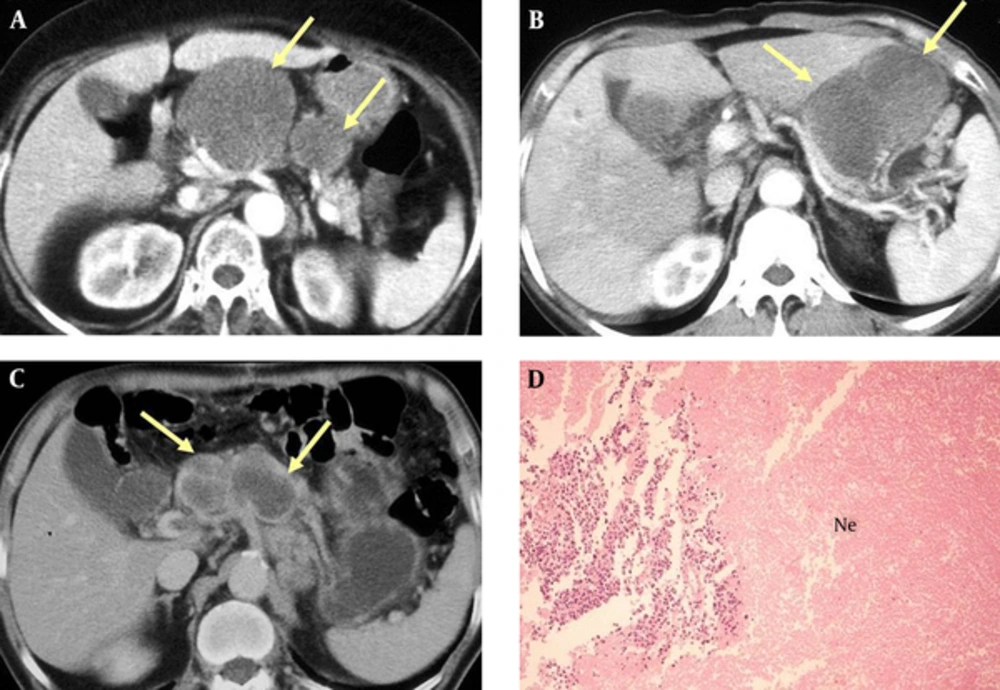

Three different patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the stomach. A - C, CT scan shows multiple large low attenuation lymph nodes (arrows) in the gastrohepatic ligament and celiac axis areas. The primary gastric mass is not shown on this image. D, Photomicrograph of histopathologic section shows massive tumoral necrosis (Ne) within enlarged metastatic lymph nodes (H & E, x 100).

4. Discussion

Gastric NECs, including small cell and large cell carcinomas, are rare. They account for 6% of gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms, are more common in men (male-to-female ratio, 2:1), and present at a mean age of 63 years (range, 41 - 61 years) (13). Histologically, the NEC component is similar to small cell or large cell NEC of the lung and corresponds to a grade 3 neuroendocrine neoplasm, according to the 2010 WHO classification (2).

The histologic features of small cell NEC are small, round, or oval lymphocyte-like cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, scanty cytoplasm, and frequent mitoses. According to a clinicopathologic study by Matsui et al. (14), gastric small cell NEC was polypoid at an early stage with a craterlike ulceration developing later within the mass. Large cell NEC is cytologically different from small cell NEC; large cell NEC has polygonal-shaped large cells, a low nuclear-cytoplasm ratio, and coarse nuclear chromatin. Large cell NEC also shows a higher mitotic rate than small cell NEC. Both gastric small and large cell NEC are highly malignant with significantly worse prognoses compared with typical adenocarcinomas (15).

According to Kim et al. (10), large cell NEC showed CT findings of ulcerofungating morphology with minimal peritumoral infiltration and combined metastatic lymphadenopathy in the perigastric area. Lee et al. (11) reported that small cell NEC showed poor contrast enhancement with exophytic growth and minimal perigastric infiltration. In our series, gastric NECs showed similar CT findings to those of previous studies (10, 11), including ulcerofungating morphology with minimal peritumoral infiltration and metastatic lymphadenopathy. On the other hand, our study showed additional CT findings compared to previous studies. Focal or diffuse low attenuations due to mucin or necrosis within the gastric masses were commonly noted. Furthermore, low attenuation lymph nodes due to necrosis were commonly observed. Liver metastasis was more commonly detected than peritoneal seeding. Finally, small cell NECs had similar CT findings to large cell NECs. There were no significant differences in CT findings between small cell NEC and large cell NEC.

In our series, distant metastases were observed in nine out of 32 patients. These patients showed rapid disease progression and a poor response to systemic chemotherapy, and later died of disseminated metastases. In cases of gastric NECs, more careful follow-up should be undertaken to provide early detection and treatment of disseminated metastases.

It is difficult to differentiate NEC from adenocarcinoma. As the incidence of gastric adenocarcinoma is higher than gastric NEC, it is difficult to consider gastric NEC upon first presentation. In our study, preoperative CT findings were interpreted as gastric adenocarcinoma (n = 29) or lymphoma (n = 3). Mucinous gastric carcinomas also have low attenuation within the tumor, according Park et al. (16) Most of the mucinous gastric carcinomas showed thickening of the diffusely low-attenuating area, which corresponded to the mucin pool located primarily in the submucosa or in deeper layers.

Our study is limited in some respects. First, the main limitation of the study is its retrospective design; our patients underwent CT using various protocols and scanners during the 11-year study period. Second, not all gastric NEC patients underwent surgery. Four cases were confirmed using endoscopic biopsy. We assumed that endoscopic biopsy had a positive predictive value of 100%. However, a false positive may occur if the biopsy specimen is interpreted incorrectly. Third, the radiologic-pathologic correlation was limited in some patients because of limited descriptions of the abnormal findings in surgical and pathologic reports. Not all of the low attenuation lesions within the tumor or metastatic lymph nodes were evaluated.

In conclusion, although gastric NECs are rare and have overlapping features with gastric adenocarcinoma, radiologists should consider gastric NECs when they encounter imaging findings such as a large ulcerofungating tumor with low attenuation areas, extensive necrotic lymphadenopathy, and frequent hepatic metastases.