1. Background

The cerebral collateral circulation refers to the subsidiary network of vascular channels that stabilize cerebral blood flow when principal conduits fail. This failure plays a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of cerebral ischemia, especially ischemia caused by severe occlusion of the internal carotid artery (ICA) or middle cerebral artery (MCA), which has a poor course (1) and high recurrence of stroke (2, 3). The primary collaterals include the arterial segments of the circle of Wills, which exhibit considerable variability and frequent asymmetry, with an ideal configuration present in only a minority of cases. As the foremost part of the secondary collaterals, the leptomeningeal collaterals (LMCs), which are also referred to as leptomeningeal anastomoses (LMAs) or pial collaterals, are small arterial connections that join the terminal cortical branches of the major (middle, anterior, and posterior) cerebral arteries along the brain surface. In chronic hypoperfusion that results from severe carotid or MCA stenosis or occlusion, the LMCs have a high frequency (4) and maintain cerebral blood flow when the primary collateral flow is insufficient. The presence of LMCs has also been associated with better outcomes, a reduced infarct size, and faster recanalization (5).

Modern diagnostic imaging techniques, such as Xenon enhanced computed tomography (CT), single photon emission CT, positron emission tomography (PET), CT perfusion, magnetic resonance (MR) perfusion, cerebral angiography (digital subtraction angiography, DSA), and transcranial doppler (TCD), have improved the assessment of cerebral blood flow via collaterals. TCD is a noninvasive technique and comprises a promising alternative to DSA for collateral supply evaluation (6, 7). Moreover, dynamic observations of the LMCs become increasingly important for clinicians when making decisions regarding interventional therapy. Several TCD studies have been published regarding the LMCs (8-14); however, no study has identified a standard for LMCs. To determine the accuracy of TCD in LMC flow assessment in patients with severe occlusive ICA and MCA disorders, we compared DSA and TCD findings in patients with these arterial disorders.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to compare the results of TCD and DSA assessments of the LMCs and to establish a reference for TCD in severe occlusive ICA and MCA disorders.

3. Patients and Methods

The experimental protocol was established according to the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki declaration and was approved by the human ethics committee of our university. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual participants.

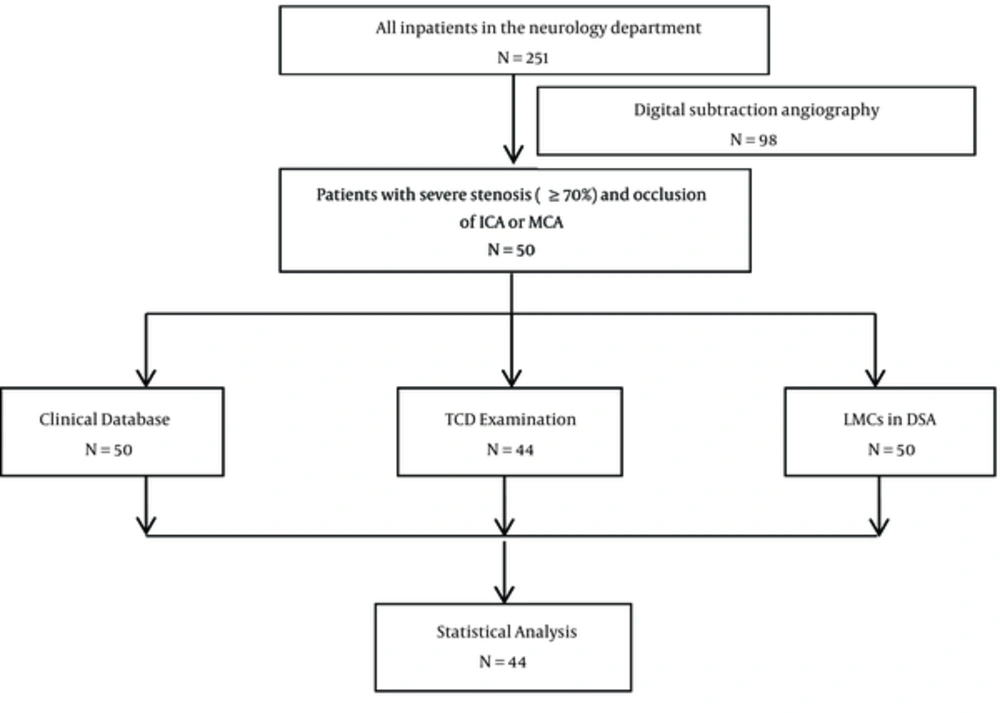

We reviewed the medical records, TCD data, and angiographic films of patients who had been admitted to the neurology department of the first affiliated hospital of Zhejiang University of China between October 1, 2010 and December 31, 2011. The inclusion criteria comprised patients with 1) severe occlusive ICA or MCA, including severe stenosis (≥ 70%) and occlusion, 2) TCD and DSA prior to endovascular treatment of the severe occlusive vessel, and 3) good temporal windows for TCD examination. The exclusion criteria included patients with stenosis in the opposite side of the ICA or MCA, both sides of the ACA, and a PCA that altered the flow velocities. Forty-four patients were eligible for analysis.

DSA was reanalyzed to determine the presence of LMCs and the degree of stenosis by a stroke neurologist who was blind to the TCD findings. The degree of stenosis was measured via comparison of the diameter of maximal narrowing (D narrow) and the diameter of the normal part immediately distal or proximal to the stenosis using the following formula: % stenosis = (1-[D narrow / D normal]) × 100% (15). The normal portion was defined as the location at which the vessel walls became parallel on angiography. We identified the LMCs on the antero-posterior and lateral projections of DSA. The presence of a LMC was determined if the distal MCA branches (M3 branches) were filled through the ACA or PCA (16). The patients were divided into two groups according to the LMCs in the DSA, including one group with LMCs the LMC group and one group without LMC (the non-LMC group).

All patients underwent a TCD examination by an experienced sonographer who was blind to the clinical characteristics and angiographic findings. A single-channel, 2-MHz Doppler device (Doppler BOX; DWL, sef-Schuettler-Strasse, Singen, Germany) was used for TCD examination. To detect the MCA and the anterior cerebral artery (ACA), the probe must be positioned at the temporal skull above the zygomatic arch in a slightly anterior direction. The MCA is located 50 - 55 mm in depth with the blood flow directed towards the probe. The ACA is characterized by blood flow away from the probe at 60 - 70 mm in depth. When the probe is positioned more posterior and inferior, the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) is identified 55 - 70 mm in depth with the flow directed away from the probe (the P2 segment).

For each patient, 7 researchers participated in data collection and analysis, and all researchers were blinded to each other. The SPSS software suite, version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), was used for all statistical analyses. Normally distributed data were expressed as means ± standard deviations. Intergroup comparisons of the clinical values were conducted via unpaired Student’s tests. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the independent factors of LMC occurrence. Furthermore, the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity were calculated via a receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis. All P-values were two-tailed and statistically significant at < 0.05. A study flow diagram is presented in Figure 1.

4. Results

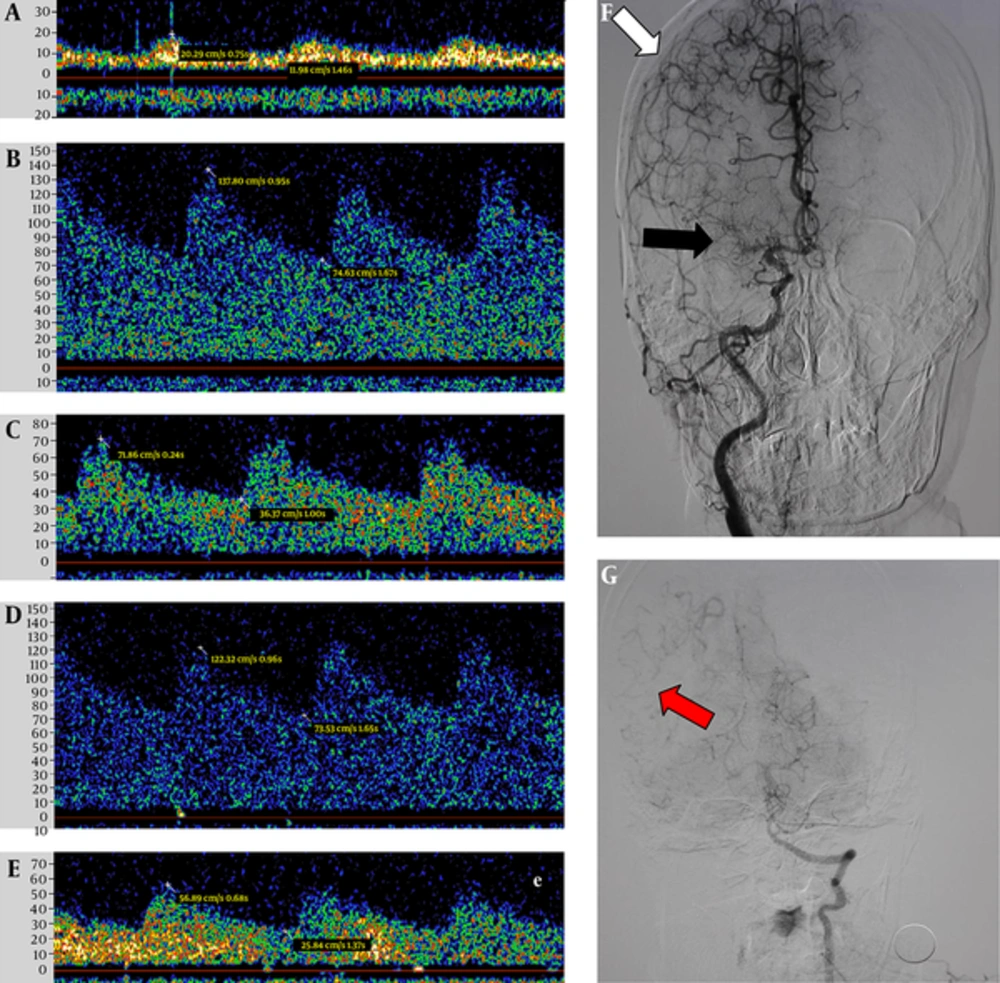

The demographics of the 44 patients are summarized in Table 1. Figure 2 indicates TCD and DSA images of a patient with MCA occlusion.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 44 |

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 60.0 ± 11.6 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 35 (79.5%) |

| Female | 9 (20.5%) |

| Stenotic vessels | |

| ICA | 32 (72.7%) |

| MCA | 7 (15.9%) |

| Both | 5 (11.4%) |

| LMCs | |

| With | 26 (59.1%) |

| Without | 18 (40.9%) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 28 (63.6%) |

| Diabetes | 12 (27.3%) |

| Smoking | 29 (65.9%) |

| Drinking | 23 (52.3%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 11 (25%) |

Abbreviations: ICA, internal carotid artery ; MCA, middle cerebral artery; LMCs, leptomeningeal collaterals; SD, standard deviation.

avalues are expressed as number or percentage.

Digital subtraction angiography and transcranial Doppler images of a 61-year-old woman with LMCA occlusion. TCD images indicate the low systolic velocity of the LMCA (A) and the substantially higher systolic velocity of the LACA (B) compared with the RACA (C), as well as the substantially higher systolic velocity of the LPCA (D) and the RPCA (E). Digital subtraction angiography indicates the occlusion of the LMCA (F, black arrow), the connections between the MCA and ACA (F, white arrow), and the connections between the middle and posterior cerebral arteries (G, red arrow).

4.1. Correlation Between the LMCs and the Clinical Data

We compared the age, history of hypertension, diabetes, smoking, drinking, and hyperlipidemia between the groups with and without LMCs. As shown in Table 2, the LMC group had a significantly lower age (odds ratio [OR] = 0.12, P = 0.005, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.032 - 0.509) and a significantly higher probability of diabetes (OR = 2.55, P = 0.037, 95% CI: 0.603 - 11.624) compared with the non-LMC group.

Abbreviation: LMCs, leptomeningeal collaterals.

aP < 0.01 LMCs vs. non-LMCs.

bP < 0.05 LMCs vs. non-LMCs.

4.2. Comparison of the Blood Flow Between the Groups with and Without LMCs

The ratios of the velocities between the stenosal side ACA (S-ACA) and the stenosal side MCA (S-MCA), opposite side MCA (O-MCA), and opposite side ACA (O-ACA) were calculated for the systolic, diastolic, and average velocities of the ACA-LMC group. As shown in Table 3, only the S-ACA/S-MCA ratios were significantly increased (P < 0.01, 95% CI: 0.568 - 0.897) in the LMC group compared with the non-LMC group.

| Velocity | LMC Group | Non-LMC Group | t Value | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-ACA /S-MCA | Systolic | 3.34 ± 0.72 | 1.26 ± 0.19 | - 3.13 | 0.003b |

| Diastolic | 3.83 ± 0.89 | 1.17 ± 0.19 | - 3.33 | 0.002b | |

| Average | 3.55 ± 0.78 | 1.23 ± 0.18 | - 3.33 | 0.002b | |

| S-ACA /O-ACA | Systolic | 1.15 ± 0.12 | 0.88 ± 0.11 | - 1.66 | 0.105 |

| Diastolic | 1.15 ± 0.13 | 1.01 ± 0.16 | - 0.67 | 0.504 | |

| Average | 1.15 ± 0.12 | 0.93 ± 0.13 | - 1.22 | 0.227 | |

| S-ACA /O-MCA | Systolic | 1.30 ± 0.20 | 1.07 ± 0.15 | - 0.92 | 0.363 |

| Diastolic | 1.37 ± 0.23 | 1.14 ± 0.15 | - 0.86 | 0.396 | |

| Average | 1.33 ± 0.21 | 1.09 ± 0.15 | - 0.911 | 0.368 |

Abbreviations: ACA, anterior cerebral artery;MCA, middle cerebral artery;LMCs, leptomeningeal collaterals;S-ACA, stenosal side-ACA;S-MCA, stenosal side-MCA;O-ACA, opposite side-ACA;O-MCA, opposite side-MCA.

avalues are expressed as mean ± SD.

bP < 0.01 LMCs vs. non-LMCs.

In the PCA-LMC group, the ratios of the stenosal side PCA (S-PCA) and the stenosal side MCA (S-MCA), opposite side MCA (O-MCA), and opposite side PCA (O-PCA) were calculated for the systolic, diastolic, and average velocities. As shown in Table 4, only the S-PCA/O-PCA ratios for the diastolic and average velocities were significantly increased (P < 0.05, 95% CI: 0.586-0.914) in the LMC group compared with the non-LMC group.

| Velocity | LMC Group | Non-LMC Group | t Value | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-PCA /O-PCA | Systolic | 1.76 ± 0.24 | 1.25 ± 0.13 | - 1.87 | 0.070 |

| Diastolic | 2.07 ± 0.34 | 1.34 ± 0.15 | - 2.25 | 0.031b | |

| Average | 1.90 ± 0.28 | 1.29 ± 0.14 | - 2.12 | 0.041b | |

| S-PCA /S-MCA | Systolic | 2.22 ± 0.59 | 1.54 ± 0.26 | - 1.20 | 0.237 |

| Diastolic | 2.55 ± 0.87 | 1.49 ± 0.28 | - 1.55 | 0.129 | |

| Average | 2.37 ± 0.71 | 1.50 ± 0.26 | - 1.43 | 0.160 | |

| S-PCA /O-MCA | Systolic | 1.37 ± 0.35 | 0.95 ± 1.32 | - 1.39 | 0.173 |

| Diastolic | 1.41 ± 0.36 | 0.98 ± 0.13 | - 1.43 | 0.161 | |

| Average | 1.39 ± 0.36 | 0.96 ± 0.13 | - 1.45 | 0.157 |

Abbreviations: PCA, posterior cerebral artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; S, stenosal side; O, opposite side.

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

bP < 0.05 LMCs vs. non-LMCs.

4.3. ROC Analysis of TCD Accuracy in LMC Assessment

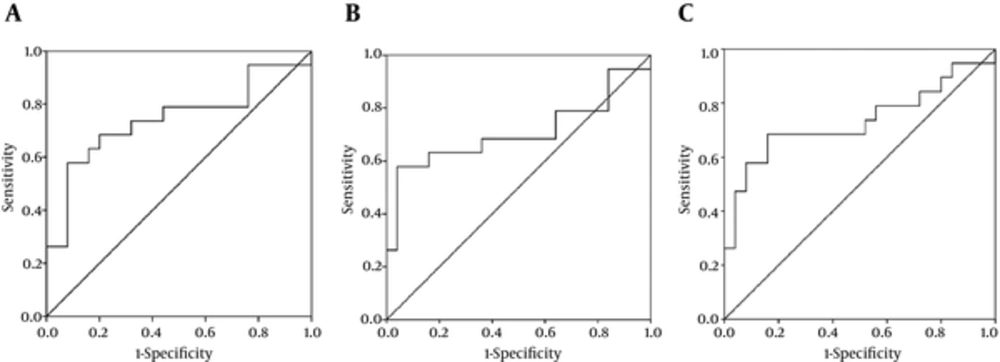

In the ACA-MCA LMC group, only the systolic velocity (AUC = 0.744, 95% CI: 0.587 - 0.901, P = 0.006), diastolic velocity (AUC = 0.710, 95% CI: 0.541 - 0.880, P = 0.020), and the average velocity (AUC = 0.735, 95% CI: 0.575 - 0.896, P = 0.009) of the S-ACA/S-MCA ratio could be assessed in the presence of the LMCs (Figure 3). The highest sensitivity (68.4%) and specificity (80.0%) were obtained when the cutoff value was 2.27 for the systolic velocity ratio. The highest sensitivity (55.0%) and specificity (95.8%) were obtained when the ratio was 1.33 for the diastolic velocity ratio. When the ratio of the average velocity was 1.38, the highest sensitivity and specificity were 65.0% and 83.3%, respectively.

A, Predictive ability of the ratio of the systolic velocity in the S-ACA and S-MCA with respect to the ACA-MCA LMCs. B, Predictive ability of the ratio of the diastolic velocity in the S-ACA and S-MCA with respect to the ACA-MCA LMCs. C, Predictive ability of the ratio of the average velocity in the S-ACA and S-MCA with respect to the ACA-MCA LMCs.

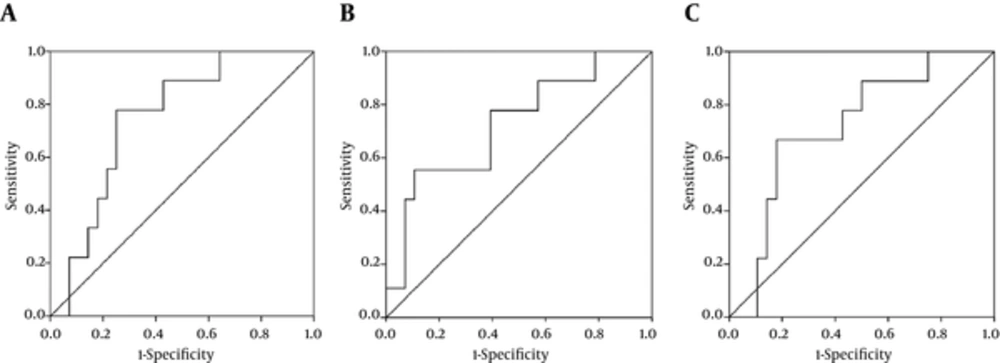

In the PCA-MCA LMC group, only the systolic velocity (AUC = 0.750, 95% CI: 0.582-0.917, P = 0.026), diastolic velocity (AUC = 0.726, 95% CI: 0.524 - 0.928, P = 0.044), and average velocity (AUC = 0.718, 95% CI: 0.530 - 0.906, P = 0.037) of the S-PCA/O-PCA ratio could be assessed in the presence of the LMCs (Figure 4). The highest sensitivity (77.8%) and specificity (75.0%) were obtained when the cut point was 1.38 in the systolic velocity ratio. The highest sensitivity (55.6%) and specificity (89.3%) were obtained when the ratio was 1.95 for the diastolic velocity. When the ratio of the average velocity was 1.25, the highest sensitivity and specificity were 55.6% and 85.7%, respectively.

A, Predictive ability of the ratio of the systolic velocity in the S-PCA and O-PCA with respect to the PCA-MCA LMCs. B, Predictive ability of the ratio of the diastolic velocity in the S-PCA and O-PCA with respect to the PCA-MCA LMCs. C, Predictive ability of the ratio of the average velocity in the S-PCA and O-PCA with respect to the PCA-MCA LMCs.

5. Discussion

Many studies have demonstrated different ways to evaluate the LMCs (17), and velocity changes for the LMCs have been reported in MCA disease (12). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no published report regarding the velocity criteria for the diagnosis of LMCs by TCD.

The first elaborate description of LMCs was provided by Heubner in 1874. TCD has been recommended by the American association of neurology for collateral pathway evaluation in conditions of ICA occlusion. Although the accuracy of TCD remains disputed because it depends on the temporal windows and the technique of the examiner, it is an indispensable approach to evaluate the vessel flow dynamically, especially in patients with endovascular treatment.

Numerous studies, which have used several imaging modalities and grading methods, suggest that the quality of LMCs is an independent predictor of outcome following acute ischemic stroke (18, 19) and predicts the response to stroke intravenous thrombolysis (20). A small number of studies have used the relative blood flow velocity and vessel pulsatility as surrogate markers for LMC flow. Flow diversion on TCD, which is defined as an increased flow velocity in the ipsilateral ACA/PCA, was correlated with the angiographic collateral grade when methods were compared, which suggests a potential role for TCD in LMC measurement. The current study used the velocity ratio of the two sides of the vessels, which decreases the error induced by individual differences and the opening of the Wills circle.

Limited reports describe the factors that affect angiographic LMCs in humans. Our study demonstrates that older patients have poorer LMCs, especially patients older than 60 years of age. The effect of diabetes on LMCs remains under debate. Diabetes may lead to impaired or excessive neovascularization in different organ systems, and the mechanism of these effects is not clear. In our study, the patients with diabetes exhibited better LMCs, which is in contrast to Lazzaro (21), who reported that there was no association between diabetes and the extent of LMCs in ischemic stroke patients. Akamatsu (22) suggests that the impaired collateral status contributes to exacerbated ischemic injury in mice with Type 2 diabetes. However, these two studies both investigated acute MCA occlusion, whereas most patients in our study exhibited chronic artery occlusion. These differential findings suggest that diabetes plays different roles in chronic and acute artery occlusion and requires further investigation.

The current study has several limitations that should be considered in the interpretation of the results. First, the sample size is relatively small; thus, this retrospective series only provides initial preliminary evidence for a reliable criterion, and further investigation via a larger, prospective study is required. Second, there was less than a 24-hour difference between the TCD and DSA examinations. Simultaneous evaluations with both techniques would provide a precise correlation between the spectrums in TCD and the LMC in DSA and should be considered in future studies. Finally, TCD is a technical examination that relies on the examiner and patient status. Although there was only one examiner involved in the current TCD assessments, some deviation remains unavoidable. Nevertheless, these novel findings provide the first evidence that there is a feasible criterion for the use of TCD in LMC evaluation.

In conclusions, TCD is a reliable tool in LMC assessment for patients with severe occlusive ICA and MCA disorders, especially the systolic velocity ratios of the S-ACA and S-MCA in anterior LMAs and the S-PCA and O-PCA in posterior LMAs.