1. Introduction

Iatrogenic venous injury to the superior vena cava (SVC) is rare, but it can rapidly rise to potentially massive hemorrhage and hemodynamic instability depending on the site of injury (extrapericardial: hemothorax, intrapericardial: hemopericardiaum). In the literature, only a few cases of iatrogenic SVC perforation have been reported (1-10). According to recent research (10) of 10 cases, four patients died of SVC perforation, two underwent a stent graft placement, two required pericardial drainage tube, and the remaining two had open surgical repair via median sternotomy. We present the case of a patient who developed right hemothorax after a left central venous catheter (CVC) placement and penetration of the SVC could be managed by coil embolization through the left subclavian CVC.

2. Case Presentation

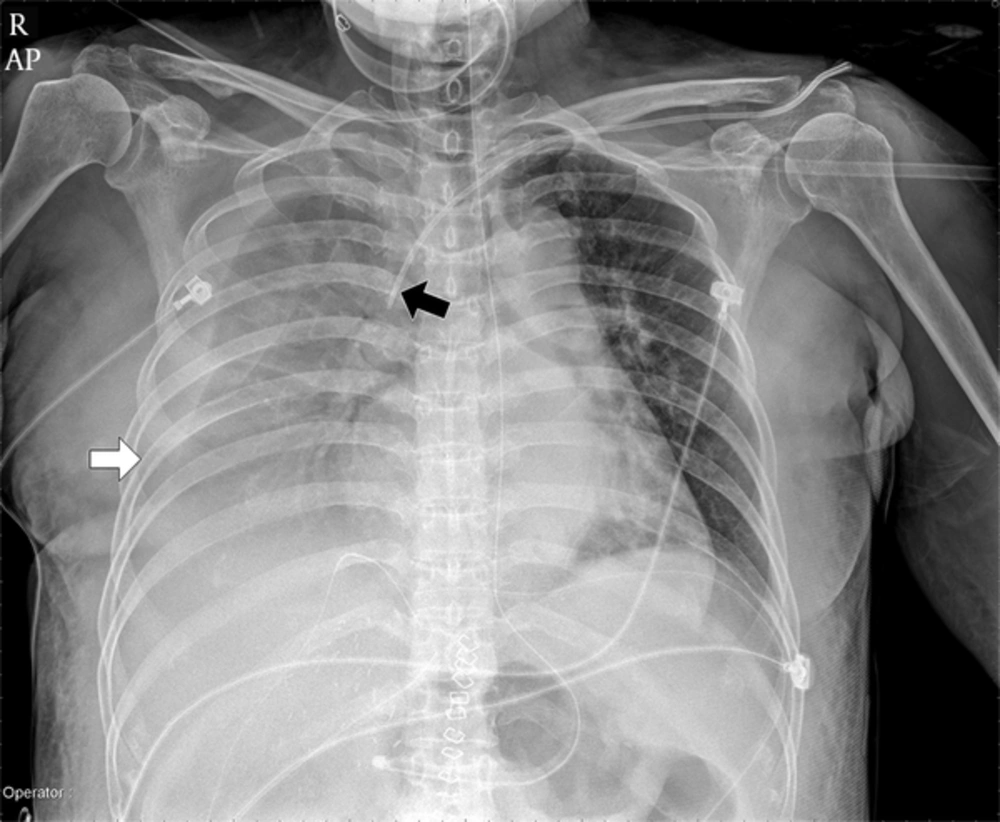

The patient is a 58-year-old female with a history of hepatitis B and liver cirrhosis who underwent liver transplantation, treated 9 days prior to coil embolization. The patient underwent a left subclavian central venous catheter (CVC) (7 Fr, 20-cm-long catheter: arrow international, reading) placement on the operating room table before liver transplantation. Postoperative chest radiography (Figure 1) obtained in the surgical intensive care unit demonstrated right pleural effusion and passive atelectasis in the right lower lung field and left subclavian CVC insertion in SVC. During three days, the right pleural effusion was observed with repeating of increasing and decreasing. Three days after liver transplantation was performed, the patient became hemodynamically unstable resulting in multiple blood transfusions. The patient’s hemoglobin was recorded at 5.9 g/dL (baseline: 12 g/dL), blood pressure dropped to a systolic pressure measurement of 75 mmHg (baseline: 110 mmHg), and oxygen saturation was recorded at 70% (baseline: 100%).

Postoperative anteroposterior chest X-ray obtained 24 hours after liver transplantation demonstrates large amount of right pleural effusion and passive atelectasis in the right lower lung field (white arrow) and left subclavian central venous catheter (CVC) insertion in the superior vena cava (SVC) (black arrow).

Based on this result, we suspected that there could be injury in the SVC. So, we checked chest CT. Contrast-enhanced chest CT revealed penetration of the lateral wall of the SVC by the tip of left subclavian CVC surrounding the pneumomediastinum (Figure 2).

Axial multiple detector computed tomography (MDCT) scan shows penetration of the lateral wall of the superior vena cava (SVC) by the tip of the left subclavian central venous catheter (black arrow) surrounding pneumomediastinum (white arrow). CT also shows a large amount of hemothorax (white arrowhead).

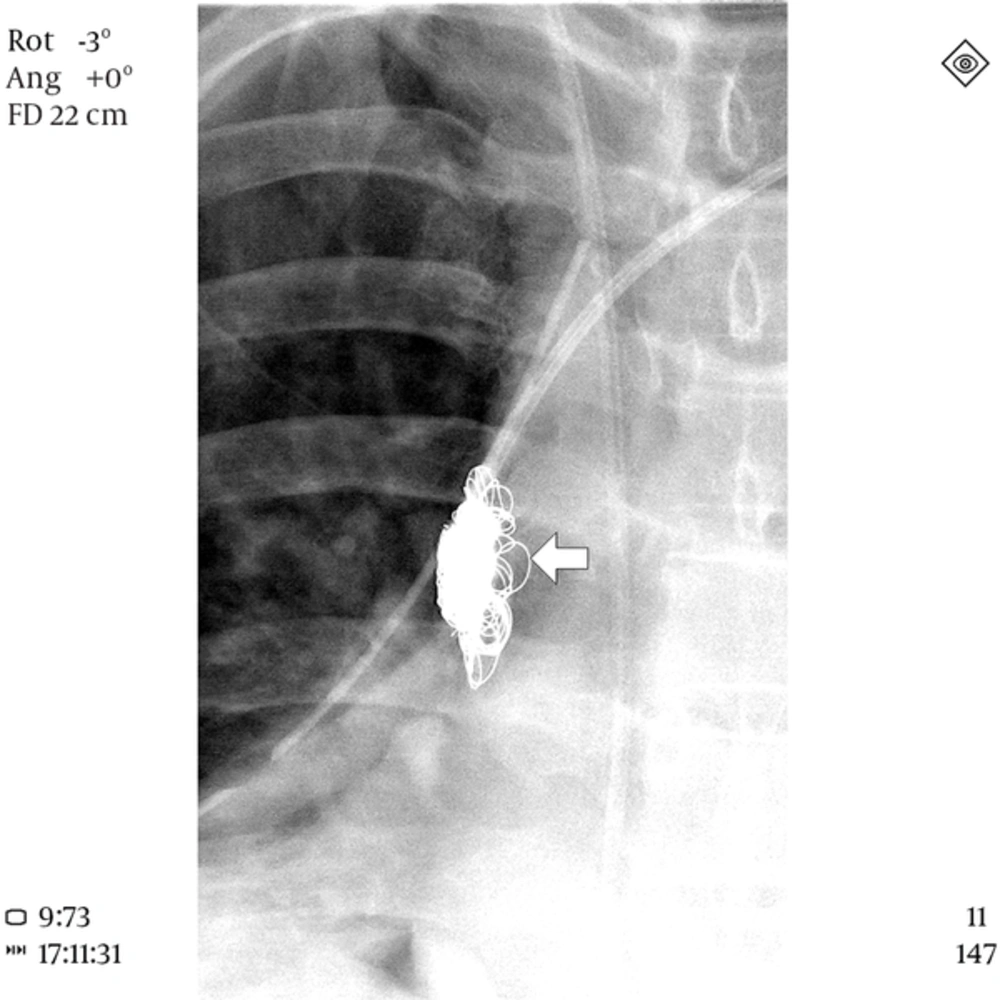

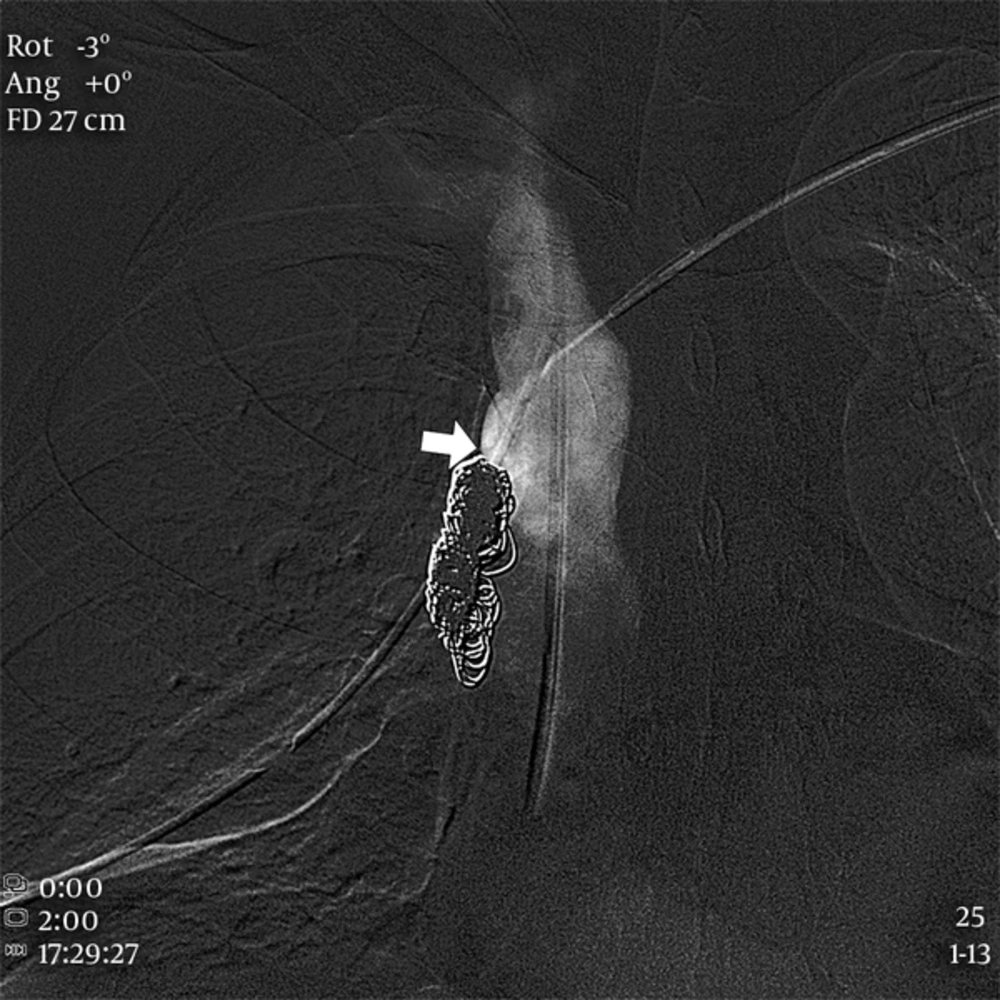

The patient was transferred immediately to the interventional radiology unit for further management. Diagnostic venography through left subclavian CVC showed extravasation of contrast media from the SVC into the right mediastinum (Figure 3). The penetration site of SVC was occluded with 16 Interlock detachable coils (Boston Scientific, MA, USA) via microcatheter (2.3 Fr Renegade, Boston Scientific, MA, USA), which was inserted through left subclavian CVC (Figure 4). Completion venography showed successful exclusion of the SVC injury (Figure 5). The CVC was subsequently removed. Immediately after the procedure, the amount of drained fluid through chest tube was decreased markedly 430 cc per day. At postoperative day 29, the patient was discharged uneventfully. Twenty four months after coil embolization the patient is still doing well.

3. Discussion

There are several reports about iatrogenic SVC injury (1-10). The etiologies were SVC stenting (2-5), balloon dilation of SVC (6, 8), subclavian dialysis catheter insertion (9, 10), central venous catheter insertion for hyperalimentation (11), and intraoperative CVC insertion (12). The detection of the injury was found during the procedure such as stenting or balloon dilation (2-6, 8), but sometimes it was found later with changes of vital signs or symptoms. So after CVC insertion, chest radiography is mandatory to confirm the location of the inserted catheter. When it is not available or uncertain, chest CT is a good diagnostic tool to detect the catheter tip location and other associating findings.

SVC injury can be treated by four different methods: balloon tamponade (1), stent-graft insertion (7), open surgical repair by median sternotomy (9), and conservative management for hemodynamically stable patients without pericardial tamponade (10, 11). They also suggested decision making factors associated with conservative management over stenting (10). In the present case, surgical repair such as open sternotomy was difficult due to previous liver transplantation, and stent-graft insertion was also difficult because the injury site was close to the left brachiocephalic vein and right atrium. Under these circumstances, coil embolization was done with packing technique within the mediastinal space to occlude the vascular injury site. Embolizing coils that were used were mechanically detachable, so there was low risk of unwanted migration into SVC or heart during procedure. Additionally, microcatheter (2.3 Fr Renegade, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) could be inserted via previously inserted central venous catheter without exchange. After embolic occlusion of injury site was performed, CVC was repositioned at SVC successfully.

When SVC injury is confirmed, it should be treated immediately depending on the patient’s condition or injury mechanism.

In summary, SVC injury due to CVC was successfully treated with detachable coil embolization without any complication.