1. Introduction

Bladder leiomyoma is a rare benign neoplasm that is most commonly seen in women in the third through sixth decades of life. It may be endovesical, intramural, or extravesical (1, 2). Ultrasound is the preferred modality for imaging of bladder neoplasms. However, bladder leiomyomas may mimic malignant lesions, and depending on the location, is often correctly diagnosed only after surgical removal (3).

2. Case Presentation

A 58-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for a bladder neoplasm that had been detected during a routine health examination. She had no obstructive or irritative urinary symptoms, and laboratory workup was normal. Sonographic examination was performed using an EPIQ 5 ultrasound machine (Philips Medical Systems, Netherlands) equipped with a transvaginal probe (C10-3v). The examination, performed with the patient in the lithotomy position, revealed a 28 mm × 16 mm × 25 mm, well-defined, hypoechoic sessile mass in the posterior wall of the bladder (Figure 1). Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) was used to detect the tumor blood flow. Informed consent was obtained before CEUS was performed. Contrast agent (SonoVue; Bracco, Milan, Italy) was mixed with 5 mL normal saline and a 2.4-mL bolus of this mixture was administered via the median cubital vein, followed immediately by a 5-mL normal saline flush. Real-time continuous ultrasound examination under a low mechanical index was used to match up this microbubble contrast agent.

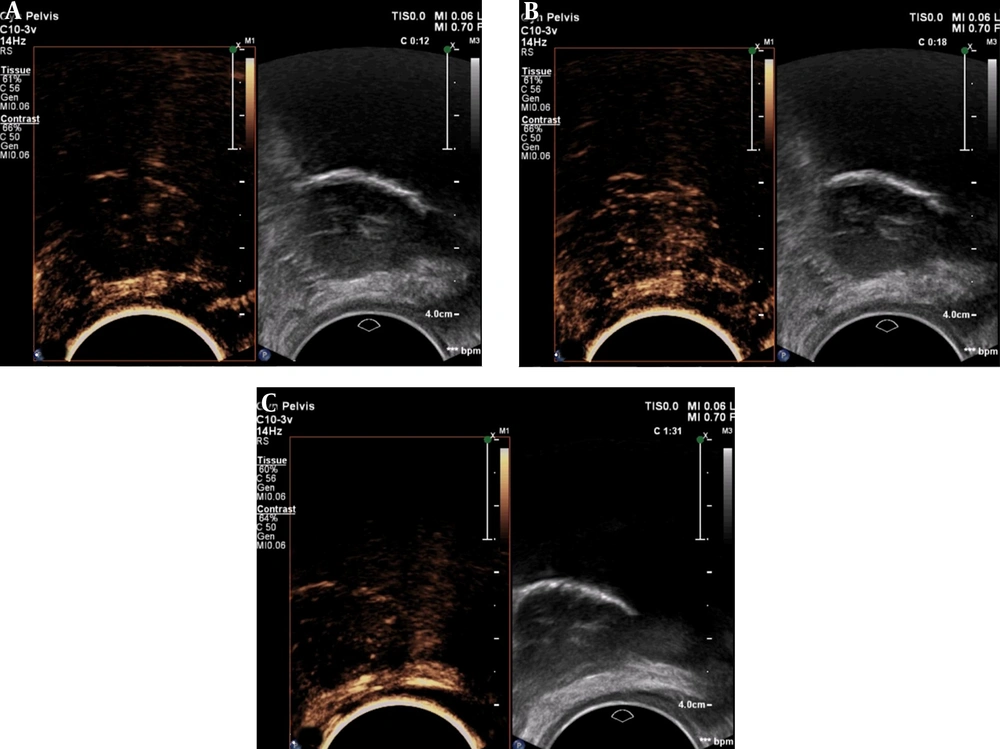

The Philips Ultrasound QVue DICOM Viewer was used for analysis of CEUS images (Figure 2). Contrast agent appeared in the mass 12 seconds after intravenous injection (Figure 2A), and the mass enhanced homogeneously. At 18 seconds, the peak time, the mass showed mild enhancement in comparison to the adjacent bladder wall (Figure 2B). Then, the contrast was washed out gradually. A small amount of contrast was still present at 91 seconds (Figure 2C).

Transurethral resection was performed. Cystoscopy showed the mass arising from the posterior wall close to the neck of the bladder. The epithelial lining in the area appeared normal. Immunohistochemical staining showed the mass to be Actin (+), Desmin (+), S-100 (−), CD34 (−), and Ki-67 (< 5%+), confirming the diagnosis leiomyoma.

3. Discussion

Bladder leiomyoma is a rare benign tumor and there are only a few reports of the pattern of enhancement in these tumors on contrast-enhanced CT and MRI (4). There are no reports of CEUS findings in bladder leiomyoma. Ultrasound examination, especially transvaginal examination, can be advantageous for diagnosis of bladder leiomyoma because of its high soft tissue resolution. Moreover, CEUS using SonoVue can give an accurate picture of tumor blood flow as this microbubble contrast agent has a strictly intravascular distribution (5).

Drudi et al. (6), showed that contrast agent is washed out of urothelial cell carcinoma (UCC) within 58 seconds of intravenous administration; whereas, in the normal bladder wall, it persists beyond 80 seconds. In our patient, microbubbles were still seen at 91 seconds, which is consistent with the normal bladder wall of Drudi et al.’s findings. Wang et al. also reported that most UCCs show fast wash-in and fast wash-out, relative to the corresponding bladder wall or prostate (7).

The ideal treatment for bladder leiomyoma has not yet been established. However, some authors have suggested that an inference can be drawn from the wide experience with uterine leiomyomas. Bladder leiomyomas have many histopathological features in common with uterine leiomyomas (1). The probability of uterine leiomyoma transforming to sarcoma is small, and there have been no reports of malignant transformation in bladder leiomyoma. Therefore, a wait-and-watch approach seems reasonable (8, 9). Correct identification of bladder leiomyoma by medical imaging will thus help avoid unnecessary surgery.

Based on the experience of this case, CEUS appears to be a good option for noninvasive diagnosis of bladder leiomyoma.