1. Introduction

Mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver is a rare benign tumor, which is mainly diagnosed during infancy. It is a tumor with variable appearances in imaging studies. The cystic form is one of the most common appearances of the tumor, and it is difficult to differentiate this tumor from other cystic lesions, such as a hydatid cyst. Mesenchymal hamartoma is associated with septation, solid components, and hemorrhagic complications more than a hydatid cyst (1). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of an adult with hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma mimicking liver hydatid disease, which was correctly diagnosed by pathology.

2. Case Presentation

A 60-year-old female patient with continuous right upper quadrant abdominal pain 5 years ago is reported. Multiple ultrasounds had been performed during the last 5 years, which revealed multiple cystic lesions of variable size with faint septation. Due to the purely cystic appearance of the lesion and being multiple in nature and with the patient having a history of direct contact with a dog as a pet, the lesion was misdiagnosed as a hydatid cyst hydatid cyst was misdiagnosed. Although the serological test for hydatid disease was negative, she had been treated with albendazole Albendazole over the last 5 years, with no clinical and radiological improvement observed. The lab results, including liver enzymes and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, were normal (WBC = 5400; HB = 13 g/dL; PLT = 284000; ESR = 18 mm; alkaline-phosphatase = 161 IU/L; AST = 23 IU/L; ALT = 28 IU/L; AFP= 1.3 ng/mL). The patient did not have a history of hepatic diseases, hepatitis, trauma, and underlying malignancy. She has been referred to our healthcare center with acutely worsening abdominal pain.

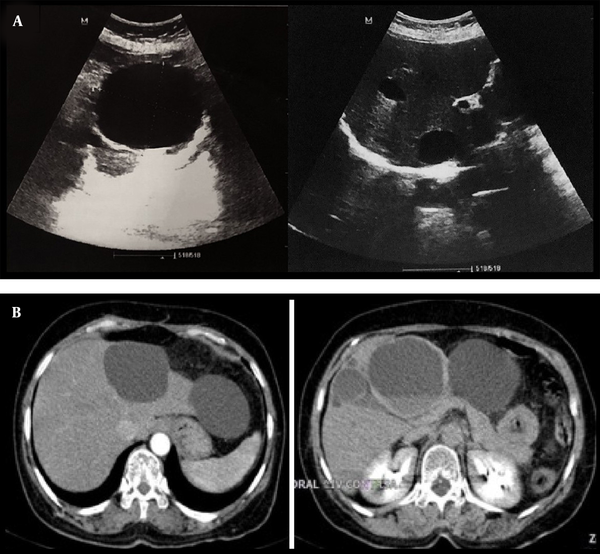

In our center evaluations, ultrasound features were not typical for hydatid. Despite her therapeutic process, she exhibited multiple lesions growing progressively in size with hemorrhagic changes (Figure 1A). An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast was considered as the next step for further characterization. The CT scan results revealed multiple thin-walled cystic lesions of variable size with a fluid-fluid level in favor of hemorrhage surrounded by fat stranding in both lobes of the liver (Figure 1B). Surgical resection for the third segment lesions was performed, and the diagnosis of mesenchymal hamartoma was confirmed based on histological findings (Figure 2).

A, Transverse abdominal ultrasound images show anechoic cystic lesions involving both hepatic lobes and variable in size (largest 76 × 62 mm); B, Abdominal CT scan (arterial and delayed phase) reveals several thin-walled cystic lesions with variable size and a fluid-fluid level suggestive of hemorrhage surrounded by fat stranding in both lobes of the liver.

At follow-up ultrasound after 1 year, there was no significant change in the size and appearance of the remaining cysts.

3. Discussion

Hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma is a rare tumor, which primarily occurs in patients aged below 2 years (2). Only a few cases of adult mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver have been reported worldwide as individual case reports. In the pathological examination, we had a disordered arrangement of the mesenchyme, hepatic parenchyma, and bile ducts (3, 4).

Chau et al. reported that children are more likely to develop solid lesions, whereas adults are more prone to have cystic variants (5). However, Hernandez et al. have shown that the tumor tends to be cystic in appearance both in children and adult populations (6). Atas et al. have demonstrated a multiseptated cystic mesenchymal hamartoma mimicking a hydatid cyst in an infant; however, septation is not common in hydatid cyst (1). In adults, women are more likely to develop a cystic tumor than a solid form, whereas no correlation has been found in men. In addition, solid cystic types are more common in women (7). The common site of tumor in the liver is the right lobe in pediatric patients and adult male patients, whereas it is commonly found in the left lobe in adult female patients. Females are more at risk of developing variants affecting both lobes of the liver (7). Based on our knowledge, this tumor is solitary most of the time, but in a few studies, multifocal lesions are also reported.

The clinical presentation of mesenchymal hamartoma depends on the patient’s age. Most pediatric cases exhibit a painless swollen abdomen, whereas diffuse abdominal pain ismore commonly observed in adult patients (3).

Although hemorrhage has been reported in mesenchymal cystic hamartomas of the lung (8), it is rare in hepatic mesenchymal hamartomas (9).

Although mesenchymal hamartoma has variable radiological features, its imaging appearance is determined by cystic or mesenchymal component predominance.

On ultrasound, the solid components of the tumor are echogenic and the cystic components appear anechoic and sometimes with septa. The cyst with septa and a solid component may exhibit little vascularity on color Doppler imaging. High-frequency ultrasound may reveal portions with tiny cysts, which appear solid with a sieve-like appearance (10, 11).

It usually has a heterogeneous appearance on a CT scan. The stromal components are isodense to the surrounding liver, whereas the cystic components appear hypoattenuating to the liver. Mesenchymal hamartoma is hypovascular and a mild increase in the solid component’s density may be seen after intravenous contrast medium administration (12).

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance of mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver is also variable and depends on the cystic versus stromal predominance and also protein content of the cyst’s fluid (12, 13). Solid parts of the tumor may appear hypointense to the surrounding liver on both T1- and T2-weighted images due to fibrosis (12). The cystic portions appear hyperintense on T2-weighted images and have variable signal intensity on T1-weighted images due to a variable protein content. Mild contrast enhancement can possibly be observed in some cases on MRI, which is limited to the stromal components and septa (12).

The differential diagnoses for predominantly cystic mesenchymal hamartoma are a simple cyst, hydatid disease, abscess, biliary cystadenoma, and mesenteric lymphangioma (14).

Hydatid cysts have variable radiological features from purely cystic to solid lesions. Purely cystic lesions are characterized by a smooth and echogenic well-defined border (15).

On CT scan, calcifications are often seen with a peripheral distribution (16), and intracystic bleeding has also been reported, although rare, as a complication of hydatid disease (17).

A hepatic abscess is usually associated with fever.

Cystic hepatoblastoma is extremely rare and tends to show early arterial enhancement.

Lymphangiomas are cystic lesions lined by endothelial cells. They are thin walled with a multilocular cystic appearance on ultrasound. On a CT scan, they appear anechoic and contain internal echoes and debris, and their attenuation depends on their content, which is chylous or serous (16).

Hepatic neuroendocrine tumor metastases can also have a cystic appearance on cross-sectional imaging, leading to misdiagnosis of benign lesions. Cystic changes are due to the central tumor necrosis (18).

Biliary cystadenomas are benign cystic neoplasms of the liver, which can be either unilocular or multilocular and may have mural nodules and papillary projections. On ultrasound, the cyst may be anechoic or can have low-level internal echo depending on their fluid content. CT scan revealed calcification and enhancement of septa and the MR signal is variable depending on its content (19).

The treatment of choice for mesenchymal hamartoma is surgical resection because of potential recurrence and malignant transformation, and although total surgical excision is gold standard, it is not possible in all patients and is dependent on the type, size, and location of the tumor. Mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver can be either regressed or transformed into malignancy so our recommendation is close follow-up rather than resection, whereas surgery is considered in the case of complications (20).

In conclusion, hepatic mesenchymal hamartomas are difficult to be diagnosed by laboratory tests or other investigations because of their nonspecific findings. Liver function tests and AFP values for mesenchymal hamartomas are usually within normal limits.

In addition, all imaging methods, including ultrasound, CT scan, and MRI, provide nonspecific findings. Hence, in the differential diagnosis of all hepatic cystic lesions in adults (although rare), the possibility of mesenchymal hamartoma should be considered, especially when typical features of common hepatic cystic lesions are not observed.