1. Background

Cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) infection is a major complication of implantable cardiac devices, leading to significant morbidity, mortality, and financial burden. The incidence of CIED infection has been reported to range from 0.13% to 19.9%. This wide range can be attributed to differences in healthcare practices, patient populations, and diagnostic methodologies across studies and regions. For instance, some areas may have stricter perioperative infection control measures or different criteria for diagnosing infections (1, 2). In recent years, the rate of CIED implantation has surged, leading to a rise in CIED infections.

The clinical manifestations of CIED infection are classified into three categories, with local infection being the most prevalent. This type accounts for more than 60% of cases and is identified by inflammatory changes, including erythema, pain, swelling, warmth, and drainage at the generator pocket, as well as erosion of the generator or a device lead. The second presentation is bacteremia or fungemia, and the third is CIED-related endocarditis (CDRIE), affecting 10 - 23% of patients. Furthermore, CIED infections are classified based on the time between cardiac device implantation and the onset of infection. Early-onset infections occur within six months of implantation, while late-onset infections appear after six months (1).

The diagnosis of CIED infection is confirmed with a combination of clinical findings, microbiologic profiles, and diagnostic imaging such as echocardiography (2). Echocardiography plays a crucial role in diagnosing CIED-related endocarditis and is effective in detecting lead and valve vegetation. Diagnosis of CDRIE by FDG-PET/CT has acceptable sensitivity and specificity (3) and is particularly beneficial in cases of possible CDRIE in the absence of pocket infection (1, 4-7).

Staphylococci, including coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) and Staphylococcus aureus, are the predominant pathogens in CIED infections. Gram-negative bacteria, other gram-positive cocci (Enterococci, Streptococci), and fungi (Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp.) have been isolated in other cases of CIED infections. Polymicrobial infections have been reported in up to 7% of patients with CIED infections, and these infections are more common in individuals with diabetes mellitus and those receiving corticosteroids (1, 5, 8-14). Complications of CIED infections include CDRIE, vertebral osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and metastatic abscess (1).

Treatment of CIED infections requires both empirical antibiotic therapy and complete hardware removal. Eventually, antimicrobial therapy should be personalized based on culture and susceptibility results (1, 5, 15-17).

2. Objectives

In the present study, we aimed to determine demographic data, comorbidities, clinical presentations, and complications concerning CIED infections.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional retrospective study was conducted at Tehran Heart Center and Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran, Iran, from March 2017 to March 2023. A total of 66 patients with confirmed CIED infections participated in the study. All patients aged 18 or older who were admitted with CIED infection were included. Patients were excluded if their medical records were incomplete or if the diagnosis of CIED infection was not confirmed based on clinical, microbiological, or imaging findings. The devices used in the patients included permanent pacemakers (PPMs), implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). Patient information was extracted from hospital documents and the health information system (HIS).

Patients with CIED infections were defined as having pocket site infections, bacteremia, CIED-related lead infection or infective endocarditis (CIED-IE). The patients' demographic characteristics, including age and sex, were noted alongside any predisposing factors such as renal failure, heart failure, diabetes, long-term corticosteroid use, chronic oral anticoagulant use, and history of CIED infection. Clinical presentations like fever and signs of infection at the pocket site were also documented. Additionally, echocardiographic findings and lab results were recorded.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IR.TUMS.THC.REC.1402.006) and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association (2000). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

The mean ± standard deviation and frequencies (percentages) were used for descriptive analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 18, for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

4. Results

Between March 2017 and March 2023, 66 patients with confirmed CIED infections participated in the study. The group consisted of 53 males (80.3%) and 13 females (19.7%), with a mean age of 59.67 ± 13.59 years, ranging from 28 to 90 years old. Among these patients, 39.4% had an ICD, 33.3% had a PPM, and 24.3% had a CRT. The baseline characteristics and risk factors for CIED infection are summarized in Table 1. The most common comorbidity was heart failure (n = 51, 77.3%), followed by a history of CIED infection (n = 21, 31.8%), diabetes mellitus (n = 14, 21.2%), and renal failure (n = 10, 15.2%). The following comorbidities had a lower prevalence rate: Chronic kidney disease, history of prosthetic valve implantation, and chronic anticoagulation therapy.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Age; range (mean ± SD) | 28 - 90 (59.67 ± 13.59) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 53 (80.3) |

| Female | 13 (19.7) |

| Heart failure | 51 (77.3) |

| History of CIED infection | 21 (31.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (21.2) |

| Renal failure | 10 (15.2) |

| History of prosthetic valve implantation | 7 (10.6) |

| Chronic anticoagulation | 7 (10.6) |

| Long-term corticosteroid therapy | 1 (1.5) |

| Malignancy | 1 (1.5) |

| History of infective endocarditis | 1 (1.5) |

| ESRD | 1 (1.5) |

| IHD | 24 (36.4) |

| Hypertension | 13 (19.7) |

| Type of implanted CIED | |

| ICD | 26 (39.4) |

| PPM | 22 (33.3) |

| CRT | 16 (24.3) |

Abbreviations: CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; IHD, ischemic heart disease; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

b The listed comorbidities are associated with CIED infections but should not be interpreted as causal risk factors.

The majority of patients in the study showed signs of pocket site infection. Specifically, 91% experienced symptoms such as redness, swelling, warmth, and drainage at the pocket site. The occurrence rates for various presentations were as follows: Device lead or generator erosion at 24.2% (16 patients), fever at 19.7% (13 patients), bacteremia at 7.6% (5 patients), and CIED-related infective endocarditis at 10.6% (7 patients). Additionally, septic pulmonary emboli were found in one patient (1.5%). Furthermore, this study found that 53% of CIED infections occurred more than six months after device implantation, while 47% occurred within six months (Table 2). The 91% prevalence of the symptoms observed in this study is higher than the rates reported in some studies, such as 60% (Bennett JE, 2019) (1).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Pocket site infection | |

| Erythema, swelling warmth, drainage | 60 (91) |

| Erosion of a devise lead or generator | 16 (24.2) |

| Fever | 13 (19.7) |

| Bacteremia | 5 (7.6) |

| CIED-related endocarditis | 7 (10.6) |

| Septic pulmonary emboli | 1 (1.5) |

| The period between cardiac device implantation and the manifestation of CIED infection (month) | |

| < 6 | 31 (47) |

| ≥ 6 | 35 (53) |

Abbreviation: CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device.

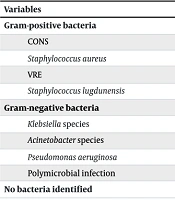

Among the 66 patients admitted with a CIED infection, 25 (37.9%) had negative cultures. Negative cultures were defined as the absence of microbial growth in blood or wound cultures after a minimum incubation period of 5 days under standard laboratory conditions. Positive cultures were identified in 41 patients with CIED infection (5 patients were positive for both blood and wound culture; 36 patients were positive for wound culture). The most frequent causative gram-positive microorganisms were CONS (n = 16, 24.2%), S. aureus (n = 14, 21.2%), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) (n = 3, 4.5%), S. lugdunensis (n = 1, 2.5%), and the most frequent gram-negative microorganisms were Klebsiella species (n = 3, 4.5%), Acinetobacter species (n = 2, 3%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 1, 1.5%). In addition, 3 patients (4.5%) had a polymicrobial infection (Table 3).

| Variables | Culture; No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Wound | Blood | |

| Gram-positive bacteria | ||

| CONS | 16 (24.2) | 3 (4.5) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 14 (21.2) | 2 (3) |

| VRE | 3 (4.5) | - |

| Staphylococcus lugdunensis | 1 (1.5) | 0 |

| Gram-negative bacteria | ||

| Klebsiella species | 3 (4.5) | 0 |

| Acinetobacter species | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 (1.5) | 0 |

| Polymicrobial infection | 3 (4.5) | 0 |

Abbreviations: CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus; CONS, coagulase-negative staphylococci.

a No bacteria identified: 25 (37.9%).

The laboratory test results, as shown in Table 4, indicated that out of the 66 patients, 24 (36.4%) had elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESR), while 23 (34.8%) were anemic. The high rates of anemia and elevated ESR among these patients suggest the presence of systemic inflammation or chronic disease, both of which are known to be associated with CIED infections. Additionally, 11 patients (16.7%) exhibited leukocytosis, and 6 patients (9.1%) had thrombocytopenia. All the patients were treated with the standard antibiotic regimen for CIED infections, and removal of the CIED system was performed in 58 patients (87.9%). No in-hospital mortality was observed among the patients.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Elevated ESR | 24 (36.4) |

| Anemia | 23 (34.8) |

| Leukocytosis | 11 (16.7) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 6 (9.1) |

| Positive wound culture | 38 (57.6) |

| Positive blood culture | 5 (7.6) |

Abbreviation: ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rates.

5. Discussion

Cardiac implantable electronic device infection is a major complication of CIED implantation, accompanied by high mortality and morbidity. The risk of CIED infection varies among different populations and depends on several factors. Some of the risk factors include age, comorbid conditions (diabetes mellitus, heart failure, renal failure, and malignancy), long-term corticosteroid therapy, and chronic anticoagulation. Furthermore, procedural characteristics such as type of intervention, device revisions, the site of intervention, pre-procedural temporary pacing, failure to administer perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis, and fever within 24 hours before implantation may play an essential role in developing CIED infection (1, 18-20).

In the current investigation, the most common predisposing factor was heart failure, followed by a history of CIED infection, diabetes mellitus, and renal failure. The following comorbidities had a lower prevalence rate: History of prosthetic valve implantation, chronic anticoagulation therapy, long-term corticosteroid therapy, malignancy, and history of infective endocarditis. As discussed previously, CIED infection typically manifests as local device infection (erosion or pocket infection), bacteremia or fungemia without pocket infection, and CDRIE. Local device infection is the most prevalent presentation of CIED infection, characterized by signs of inflammation at the generator pocket site, including erythema, wound dehiscence, erosion, tenderness, or purulent drainage. The CDRIE, on the other hand, involves infections of electrode leads, cardiac valves, or the endocardial surface (1, 15, 18).

The present study reveals that the most common presentation among patients was pocket site infection. A significant 91% of patients experienced erythema, swelling, warmth, and drainage at the pocket site. Additionally, 24.2% (n = 16) had erosion of a device lead or generator, 19.7% (n = 13) had a fever, 7.6% (n = 5) had bacteremia, and 10.6% (n = 7) had CIED-related endocarditis, respectively. The pocket can get infected during the device implantation, subsequent manipulation of the generator, or erosion of the generator or subcutaneous electrodes. Alternatively, infections might occur through hematogenous seeding due to bacteria or fungi spreading from another infected area in the body.

As discussed earlier, CIED infections are classified as early-onset (within six months of device implantation) and late-onset (after six months of implantation). Microbial contamination of the device at the time of implantation is the predominant mechanism for most early-onset CIED infections, and hematogenous seeding of leads is the major mechanism for most late-onset CIED infections (1, 18). In the current study, 53% of CIED infections occurred more than six months after device implantation, while 47% occurred within six months. This shows no significant difference between the rates of early-onset and late-onset CIED infections.

The diagnosis of CIED infection is confirmed with a combination of clinical findings, microbiologic profiles, and diagnostic imaging such as echocardiography (2). Before initiating empirical antibiotic treatment, it is crucial to obtain two blood culture sets from any patient suspected of having a CIED infection. For those with a pocket infection, swab samples of any draining pus should also be collected for cultures (1, 18). In the present research, blood cultures were taken from all patients to determine the type of microorganisms. Additionally, for patients with pocket infections, swab samples of the draining pus were collected for cultures.

Among the 66 patients admitted with a CIED infection, 25 (37.9%) had negative cultures. Positive cultures were identified in 41 patients with CIED infection (five patients were positive for both blood and wound culture; 36 patients were positive for wound culture). The high prevalence of culture-negative results (37.9%) in our study may be attributed to the widespread use of antibiotics before seeking medical care. This practice, which is common in our region, could suppress microbial growth, leading to false-negative culture results. As with past studies (1, 21), the current research shows that less than half of patients with CIED infections exhibit abnormal lab results like leukocytosis, anemia, or an ESR. Therefore, the absence of these findings does not rule out a CIED infection.

As previous studies have shown, staphylococci, including CoNS and S. aureus, are the predominant pathogens in CIED infections. Gram-negative bacteria, other gram-positive cocci (enterococci, streptococci), and fungi (Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp.) were isolated in other cases of CIED infections. Polymicrobial infection has been reported in up to 7% of patients with CIED infection (1, 5). In the present study, the most common causes of CIED infections were CoNS (n = 16, 24.2%) and S. aureus (n = 14, 21.2%). The less common microorganisms were VRE, S. lugdunensis, Klebsiella species, Acinetobacter species, and P. aeruginosa. In addition, 3 (4.5%) patients had a polymicrobial infection.

Some complications of CIED infections include infective endocarditis, vertebral osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and metastatic abscess (1). According to this study, CIED-related endocarditis was found in seven patients (10.6%), and septic pulmonary emboli were detected in one patient (1.5%). The CIED infections must be treated with empirical antibiotic therapy directed at MRSA and Gram-negative bacteria, concomitant with complete hardware removal. Eventually, the best antibiotic treatment for CIED infections should be personalized and based on culture and susceptibility results (1, 5). In the current investigation, all patients were treated with the standard antibiotic regimen for CIED infections, and removal of the CIED system was performed in 58 patients (87.9%).

Further studies should focus on advanced diagnostic modalities, such as molecular techniques (e.g., PCR) and imaging technologies like FDG-PET/CT, to improve detection rates in culture-negative cases. These tools could provide a more accurate diagnosis, especially in complex cases where traditional methods fall short.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, due to the high prevalence of culture-negative CIED infection and the low sensitivity of laboratory findings such as leukocytosis, anemia, and elevated ESR in CIED infection patients, diagnosing CIED infection can be challenging in cases where pocket site inflammatory changes or device erosion is absent. In these cases, the diagnosis of CIED infection should be confirmed with a combination of clinical findings, microbiologic techniques, echocardiography, new imaging modalities such as 18 FDG-PET/CT, and the physician's clinical judgment.