1. Context

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a serious and relatively rare condition characterized by elevated blood pressure within the pulmonary arteries, which increases strain on the right ventricle of the heart (1, 2). The pathophysiology of PAH involves complex mechanisms, including vascular remodeling, endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, impaired nitric oxide signaling, and genetic factors such as mutations in the BMPR2 gene (3, 4). A hallmark of PAH is the remodeling of small pulmonary arteries, characterized by smooth muscle cell proliferation, endothelial cell dysfunction, and excessive extracellular matrix deposition. These pathological changes result in the narrowing of pulmonary arteries and increased vascular resistance (5).

In PAH, there is often a predominance of vasoconstrictive and pro-proliferative signals that contribute to elevated pulmonary artery pressure. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines further promote vascular remodeling and exacerbate endothelial dysfunction (6). Additionally, reduced nitric oxide production impairs vasodilation, leading to heightened pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). Genetic mutations disrupt normal signaling pathways that regulate smooth muscle cell proliferation and apoptosis, further complicating the disease (7).

Current treatment options for PAH include phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (tadalafil and sildenafil), soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators (riociguat), endothelin receptor antagonists (bosentan, ambrisentan, and macitentan), and prostacyclin pathway modulators (epoprostenol, treprostinil, iloprost, and selexipag) (8, 9). While these therapies can slow disease progression and improve hemodynamics and quality of life, there remains an urgent need for more effective treatments targeting additional pathways to enhance patient outcomes (10), reduce mortality and morbidity (11), and specifically address the typical characteristics of pulmonary vascular remodeling (12).

Sotatercept is a novel therapeutic agent that has shown promise in early clinical trials for the treatment of PAH (13, 14). This fusion protein consists of the extracellular domain of human activin receptor type 2A linked to the Fc domain of human IgG1. Sotatercept works by rebalancing anti-proliferative and pro-proliferative signaling pathways through its interaction with transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) family ligands (15-17). Specifically, it aims to restore the function of bone morphogenic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR2), which plays a crucial role in maintaining pulmonary artery integrity and reducing endothelial dysfunction (18-20).

2. Objectives

This review seeks to evaluate the existing evidence regarding the efficacy and safety profile of sotatercept as a treatment for PAH. A comprehensive search of digital databases will be conducted to identify relevant studies, and the quality of evidence will be assessed using established methodologies. The findings from this review will provide valuable insights into the potential role of sotatercept as a novel therapeutic approach for PAH and inform future research directions and clinical practices.

3. Methods

3.1. Protocol

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (21).

3.2. Search Strategy and Study Selection

A comprehensive bibliographic search was conducted across multiple databases, including PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, from inception until January 18, 2024. The search utilized keywords such as “Sotatercept” and “pulmonary arterial hypertension”, along with their corresponding medical subject headings (MeSH) terms. No language restrictions or other filters were applied to ensure a broad scope of relevant literature. The complete search strategy for each database is detailed in the Supplementary Materials (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File). Additionally, the references of retrieved articles were manually reviewed to further minimize the risk of missing relevant studies. Grey literature, including unpublished or non-conventional sources, was excluded to avoid potential biases associated with less widely disseminated research.

All search results were imported into EndNote version 21, where duplicate entries were systematically removed. The remaining studies were then imported into the Rayyan platform for further screening. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of the identified studies to select those meeting the inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through discussion. Studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of sotatercept in patients with PAH were included based on the following criteria: (1) Prospective, retrospective, cross-sectional studies, or clinical trials involving human subjects, (2) participants aged 18 years or older, (3) diagnosed cases of PAH, and (4) studies including at least one group receiving sotatercept as a therapeutic intervention.

Exclusion criteria encompassed: (1) Reviews, conference abstracts, case reports, case series, and letters to editors, (2) animal studies, (3) non-English publications, and (4) studies lacking full-text availability.

3.3. Data Extraction

Data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers, with the results cross-verified by a third reviewer to ensure accuracy. The extracted data included the study title, first author, year of publication, country of origin, study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, sample size, sotatercept administration protocol, participants’ demographics (mean age and gender percentage), disease severity, and clinical outcomes such as pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP), PVR, mean right atrial pressure (mRAP), mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP), 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), improvements in World Health Organization functional class (WHO FC), and reported adverse events, including thrombocytopenia, bleeding, headaches, telangiectasia, increased blood pressure, nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, and epistaxis.

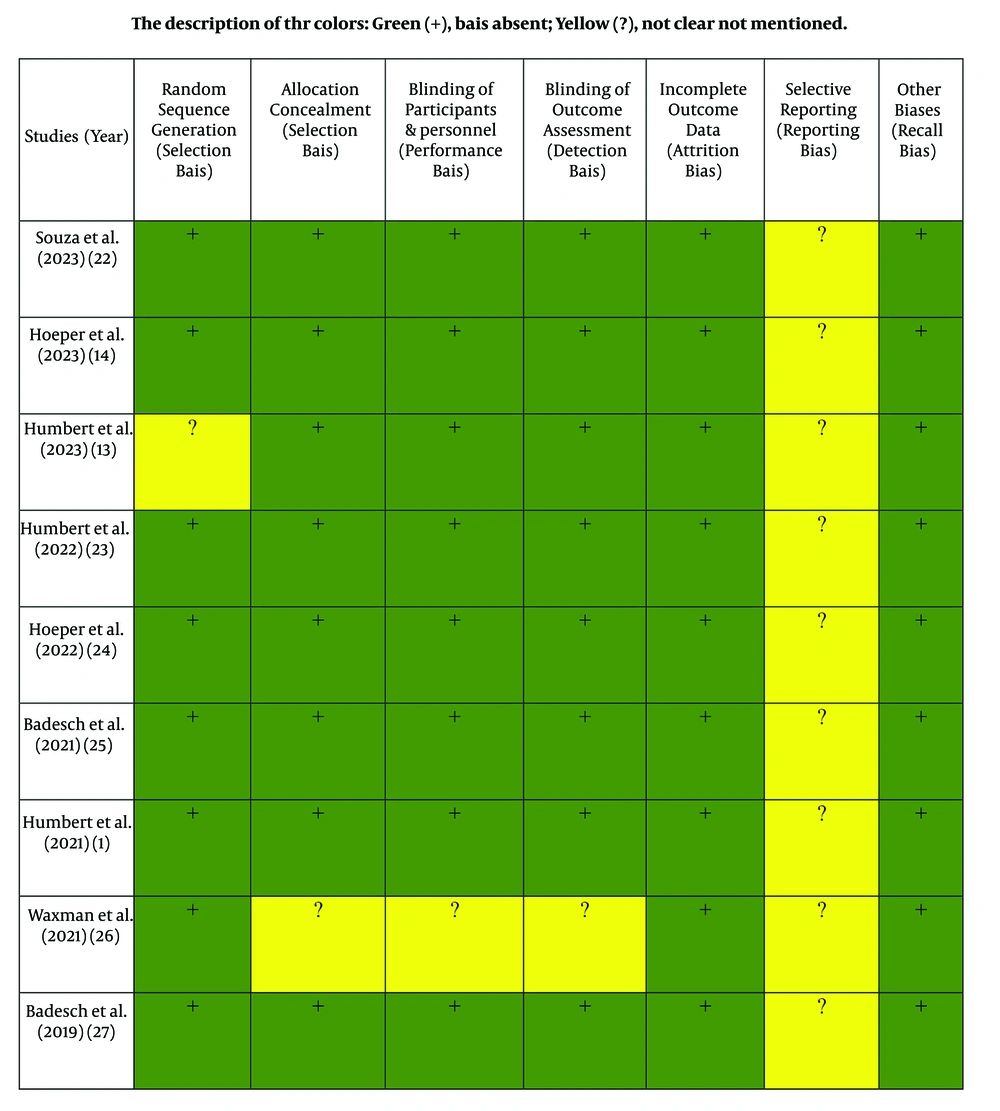

3.4. Quality Assessment

The quality of each included study was evaluated independently by two reviewers using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. The evaluation focused on seven indicators: Random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other biases (e.g., recall bias). Each item was rated qualitatively as "yes" (1 point), "cannot determine" (0.5 points), or "no" (0 points). The total score ranged from 0 to 7 points, with higher scores indicating higher study quality. Studies exhibiting low quality (defined as having more than four biases) were excluded from this systematic review (Figure 1).

3.5. Statistical Methods

Statistical methods are presented in Figure 2 and Table 1.

| Studies (Year) | Country (N) | Study Design | Follow Up Duration (Wk) | Population No. | Mean Age | Gender (Female %) | WHO FC | BMI Mean | Intervention | Outcomes | Mean PVR After Intervention | Quality Score |

| Souza et al. (2023) (22) | 21 | Post-hoc analysis of double blind, phase 3, placebo-controlled trial | 24 | 323 | 47.9 ± 14.8 | 79.3 | II/III | 26.4 ± 5.9 | Placebo, 0.3 mg/kg sotatercept, 0.7 mg/kg sotatercept | mPAP, PVR, mRAP, mixed venous oxygen saturation, PA elastance, PA compliance, cardiac efficacy, RV work, RV power, TAPSE, end systolic, and end diastolic RV areas, tricuspid regurgitation, RV fractional area change | In sotatercept group = 545.8 ± 265.2 and in placebo group = 779.3 ± 335.1 | High |

| Hoeper et al. (2023) (14) | 21 | Double blind, phase 3 trial | 24 | 323 | 47.9 ± 14.8 | 79.3 | II/III | 26.4 ± 5.9 | Placebo, 0.3 mg/kg sotatercept, 0.7 mg/kg sotatercept | 6MWD, PVR, NT-proBNP, time to clinical worsening, WHO-FC changes | In sotatercept group = 781.3 ± 398.5 and in control group = 745.8 ± 31 | High |

| Humbert et al. (2023) (13) | 8 | Double blind, phase 2 trial, placebo-controlled | 72 | 106 | 47.6 ± 14.2 | 87 | II/III | 27.1 ± 5.9 | Placebo, 0.3 mg/kg sotatercept, 0.7 mg/kg sotatercept | Long-term efficacy and safety of sotatercept | In sotatercept group = 538 ± 199 and in placebo group = 583 ± 310 | High |

| Humbert et al. (2022) (23) | 8 | Double blind, phase 2 trial, placebo-controlled | 24 | 106 | - | - | II/III | - | placebo-crossed group: Sotatercept 0.3 or 0.7 mg/kg; continued-sotatercept group: Sotatercept 0.3 or 0.7 mg/kg | PVR, 6MWD, WHO FC changes, NT-proBNP | Change from baseline to months18 - 24 in placebo group = -223 ± 58 and sotatercept = -213 ± 254 | High |

| Hoeper et al. (2022) (24) | 8 | Double blind, placebo-controlled trial | 24 | 106 | - | - | II/III | - | placebo-crossed group: Sotatercept 0.3 or 0.7 mg/kg; continued-sotatercept group: Sotatercept 0.3 or 0.7 mg/kg | Multiple component improvement (WHO FC changes, NT-proBNP, 6MWD) | - | High |

| Badesch et al. (2021) (25) | 8 | Double blind, placebo-controlled trial | 24 | 106 | - | - | II/III | - | placebo-crossed group: Sotatercept 0.3 or 0.7 mg/kg; continued-sotatercept group: Sotatercept 0.3 or 0.7 mg/kg | 6MWD, NT-proBNP, WHO FC changes | - | High |

| Humbert et al. (2021) (1) | 8 | Double blind, phase 2 trial | 24 | 106 | 48.3 ± 14.3 | 87 | II/III | 27.1 ± 5.9 | Placebo, 0.3 mg/kg sotatercept, 0.7 mg/kg sotatercept | PVR, 6MWD, NT-proBNP, TAPSE, clinical worsening, PAWR, mPAP, cardiac output, WHO FC changes | In sotatercept group with dosage: 0.3 mg/kg = 789.4 ± 287.2, in sotatercept group with dosage: 0.7 mg/kg = 755.9 ± 411.3, both sotatercept; dose groups = 770.4 ± 361.0 and in placebo group = 797.4 ± 322.6 | High |

| Waxman et al. (2021) (26) | USA | Phase 2a single-arm, open lable study | 24 | 10 | ≥ 18 (y) | - | III | - | Placebo, 0.3 mg/kg sotatercept, 0.7 mg/kg sotatercept | VO2 max change, 6MWD, total work load, VE/VCO2 slope, Ca-v02, mPAP, PAWP, mRAP | - | Moderate |

| Badesch et al. (2019) (27) | 8 | Double blind, placebo-controlled trial | 24 | 100 | ≥ 18 (y) | - | II/III | - | Placebo, 0.3 mg/kg sotatercept, 0.7 mg/kg sotatercept | PVR | - | High |

Abbreviations: PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; VO2 max, maximum oxygen consumption; 6MWD, 6-minute walk distance; WHO-FC, World Health Organization functional class; VE/VO2 slope, ventilatory efficacy; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PAWP, pulmonary artery wedge pressure; mRAP, mean right atrial pressure; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; PA, pulmonary arterial; RV, right ventricle.

4. Results

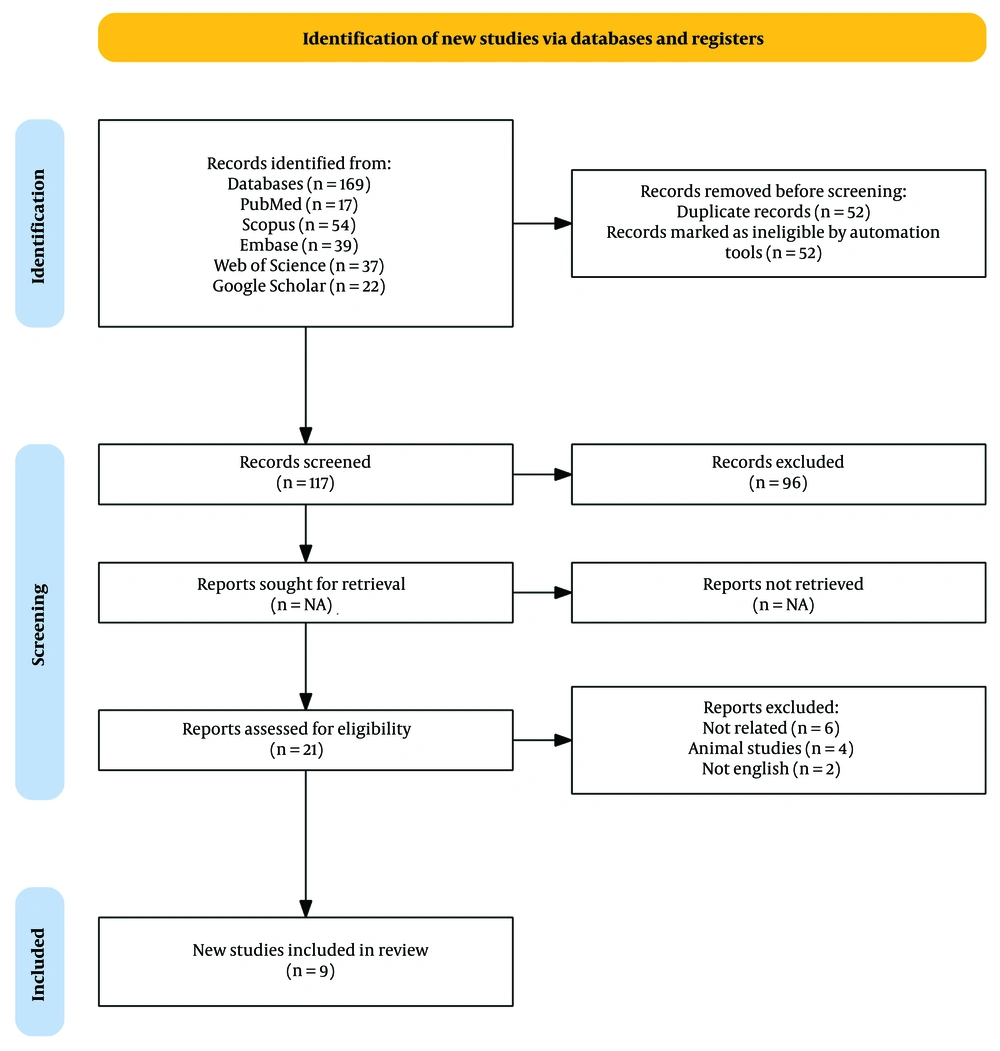

Figure 2 summarizes the step-by-step process of conducting this study. A comprehensive database search resulted in 169 studies. After eliminating duplicates and screening the titles, abstracts, and full texts, 9 articles were identified that met the inclusion criteria. These articles, published between 2019 and 2023, evaluated the effect of sotatercept on PAH (Table 1). The included studies comprised various clinical trials, including one double-blind phase 3 trial (14), four double-blind phase 2 placebo-controlled trials (1, 13, 23, 26), three double-blind placebo-controlled trials (24, 25, 27), and one post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial (22).

The study included a diverse patient population, with sample sizes ranging from 10 to 323 individuals diagnosed with PAH. All participants were over 18 years of age. Sotatercept was administered at prescribed doses ranging from 0.3 mg/kg to 0.7 mg/kg, with treatment intervals occurring every three weeks for varying durations. In eight studies, the intervention period lasted 24 weeks (1, 14, 22-27), while one study extended the duration to 72 weeks (13).

Notably, two studies conducted by Hoeper et al. (2023) (14) and Humbert et al. (2023) (1) reported significant reductions in pulmonary artery pressure following sotatercept treatment. Specifically, the mean PVR in the sotatercept group ranged from 545 to 785 (1, 13, 14, 22, 23), compared to a mean of 802 in the placebo group (13, 23). The median change from baseline in PVR varied from a decrease of 163 to 226 in the intervention group across four studies (1, 13, 14, 22), while one study reported a slight increase of 3 (23). In contrast, the placebo group exhibited changes ranging from a decrease of 16 to 223 across three studies (1, 13, 23), with one study reporting an increase in resistance (14).

NT-proBNP levels measured in the intervention group ranged from 774 to 1121 across three studies (1, 13, 14). The median change from baseline in NT-proBNP levels for the intervention group varied from a decrease of 230 to 996 (1, 13, 14, 22). In contrast, the control group exhibited an increase ranging from 58 to 310 based on two studies (1, 14), while one study reported a decrease of 506 (13). Mean cardiac output in the intervention group ranged between 4.6 and 4.8 (1, 13, 14, 22), compared to approximately 4.5 in the control group (13). The Mean Cardiac Index was reported as between 2.6 and 2.7 in the intervention group (1, 13, 14, 22) and approximately 2.5 in the control group (13).

Regarding hemodynamic parameters, mPAPs were reported at values of 52.6, 66.8, and 39.6 in three studies (14, 22, 26), with reductions of approximately 11.6 and 13.6 observed in two studies (22, 26). Right atrial pressures ranged from 5.7 to 10.9 across three studies (1, 13, 14, 22, 26), with mean decreases of -6.2 and -2.4 reported in two studies, respectively (1, 13, 14, 22, 26). Pulmonary arterial wedge pressures ranged from 9.1 to 10.3 in four studies (1, 13, 14, 22) and were recorded at 19.8 in one study (26), with mean decreases of -9.7 and -0.71 noted in two studies (22, 26). Mixed venous oxygen saturation was reported to range from 67 to 70 (14, 22).

The 6MWD did not differ significantly between the sotatercept and placebo groups; however, median changes from baseline indicated greater improvements in three studies within the sotatercept group compared to the placebo group (ranging from 7.1 to 39.89 m) (1, 14, 22), while results were similar in two other studies (13, 23). Adverse events were less frequent among participants receiving lower doses; nonetheless, occurrence rates were similar at 87.5% across both groups (1, 13, 14). Sotatercept-related adverse events were reported in 41% of cases compared to 25.6% in the control group (14). The discontinuation rate due to drug-related issues was approximately 2% in the sotatercept group versus 6% in the placebo group (14). Withdrawal rates from clinical trials were 1.8% for the intervention group and 3.1% for the placebo group (14). In the placebo group, 3.8% of cases resulted in death, while severe complications occurred in 8% of the intervention group compared to 13% in the control group (14).

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were observed in at least 30% of cases and increased with higher doses of sotatercept. Approximately 5% to 10% of TEAEs resulted in the discontinuation of either the drug or placebo (1, 13, 14). The rates of TEAEs were similar between both groups; however, fewer than 10% of participants were excluded due to TEAEs — most commonly reported among those receiving placebo — and nearly 3% of TEAEs resulted in death.

Thrombocytopenia was more prevalent among participants receiving sotatercept, with reports of adverse events increasing as dosage increased (1, 13, 14). One study noted that bleeding events occurred twice as frequently as in the placebo group (14). Increased blood pressure was reported at six times the rate observed in the placebo group (14). Telangiectasia was noted in 10% of participants across three studies (13, 14, 23). Headaches were reported in three studies but improved over time (1, 13, 14). Nausea occurred more frequently at higher doses in both the drug and placebo groups (1, 14), while diarrhea was more common among low-dose recipients but decreased over time (1, 13, 14). Fatigue was noted in two studies (1, 14), epistaxis appeared in one study, and dizziness was reported in two studies (1, 14). Overall, adverse events were more common among participants receiving sotatercept compared to those receiving placebo.

5. Discussion

The present study found that sotatercept was effective in reducing pulmonary artery pressure, improving NT-proBNP levels, and reducing right atrial pressure without altering cardiac output or pulmonary capillary wedge pressure in the intervention group. Additionally, oxygen consumption and ventilation efficiency showed improvement, while the cardiac index remained the same in both groups.

Sotatercept has been studied in relation to various hematologic diseases, including β-thalassemia (28), chronic renal anemia (29), chemotherapy-induced anemia (30), and anemia and osteolytic bone disease in multiple myeloma (31, 32), with demonstrated beneficial effects. Sotatercept is an innovative fusion protein composed of the extracellular domain of the human activin receptor type IIA fused to the Fc domain of human IgG. It works by trapping signaling molecules from the TGF-β superfamily, thereby restoring balance between the activin growth pathway, which promotes growth, and the BMP pathway, which inhibits growth (14).

One of the critical aspects of PAH is the elevation of right atrial pressure caused by increased resistance in the pulmonary circulation. This elevated pressure can lead to right heart failure and other complications. Sotatercept, by targeting activin and related factors, modulates the hallmark harmful and destructive features of PAH. Although treatments such as digoxin (a positive inotrope and negative chronotrope) and diuretics (which remove excess fluid from the body) have been mentioned for PAH, sotatercept, with its unique mechanism of action, has been proposed as a first-line treatment for this condition (6).

Based on preclinical evidence, sotatercept may directly affect pulmonary vascular regeneration, potentially influencing pulmonary artery pressure (33). Pulmonary vascular remodeling, which impacts all layers of the vessel wall, is primarily driven by increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis of endothelial and smooth muscle cells (34). By reducing right atrial pressure while maintaining cardiac output, sotatercept may help improve hemodynamics in patients with PAH, potentially enhancing their functional capacity and quality of life (7).

The intervention group demonstrated improved walking distance compared to the control group. The Gsα-protein activates adenylyl cyclase (AC), increasing the production of the cAMP second messenger involved in the vasodilation pathway. Therefore, it is anticipated that with the improvement of pulmonary hemodynamics, pulmonary capacity and exercise tolerance will also improve (35).

The decrease in NT-proBNP levels (230 to 996) suggests that sotatercept can improve cardiac function in patients with PAH, which is crucial for enhancing exercise tolerance and long-term outcomes. Sotatercept’s ability to effectively modulate the TGF-β superfamily, reduce PVR, improve right heart function, enhance oxygen delivery, decrease symptoms such as dyspnea (shortness of breath) and fatigue during exertion, and increase functional capacity, cardiovascular fitness, and muscle strength highlights its potential for improving exercise tolerance in patients with PAH (20).

In at least 30% of cases, serious adverse effects required emergency intervention, and increased doses of this medication exacerbated these effects. In approximately 5 - 10% of cases, these adverse effects led to discontinuation of the drug or placebo. The incidence of serious adverse effects was similar between the drug and placebo groups. Fewer than 10% of individuals withdrew from the study due to serious adverse effects, with most reports coming from the placebo group. Approximately 3% of cases with serious adverse effects resulted in death, which was more common at higher doses.

In this study, adverse effects were more common at higher doses. Adverse effects were similar in over 85% of cases in both the intervention and placebo groups. Adverse effects led to withdrawal from clinical trials in 1.8% of cases in the intervention group and 3.1% in the placebo group. In the placebo group, 3.8% of cases resulted in death, while 8% of cases in the intervention group and 13% in the control group experienced severe adverse effects.

Other reported adverse effects of sotatercept included thrombocytopenia, bleeding events, increased blood pressure, headache, nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, epistaxis, and dizziness. Diarrhea and headache were observed to decrease over time.

In patients with hematologic disorders, the incidence of complications is typically high, with at least 80% experiencing some form of complication. Additionally, the occurrence of TEAEs is at least 20%. However, sotatercept has been identified as an effective and satisfactory long-term treatment option for these patients. This finding contrasts with results from a previous study on anemia related to ESKD (29, 36, 37).

Regarding mortality associated with high doses of sotatercept, it is likely that individuals requiring higher doses had more severe disease, and death can be considered a consequence of their underlying condition.

Given the higher incidence of side effects associated with high doses of sotatercept, adjusting the therapeutic dose or combining it with supportive drugs may help minimize adverse reactions. This approach could prevent excessive accumulation of the drug in the body and improve treatment outcomes.

Adjusting the therapeutic dose or combining sotatercept with supportive drugs may help minimize adverse reactions and prevent excessive accumulation of the drug in the body, ultimately improving treatment outcomes and patient adherence. This approach is particularly important given the higher incidence of side effects associated with high doses of sotatercept.

In addition, a study by Lan et al. (2023) demonstrated the therapeutic efficacy of sotatercept in managing anemia and lytic bone disease in patients with multiple myeloma, supporting the findings of the present study. However, it is important to note that sotatercept has specific pharmacokinetic properties, including low tissue distribution, a long half-life, and a tendency to accumulate, which should be considered when prescribing and monitoring the drug (38).

Furthermore, Lan et al. (2023) demonstrated the therapeutic efficacy of sotatercept in managing various types of anemia and lytic bone disease in patients with multiple myeloma, which supports the findings of the present study (38).

Nevertheless, it is important to note that sotatercept has low tissue distribution, a long half-life, non-dialyzable properties, and a tendency to accumulate. These factors should be carefully considered when prescribing and monitoring the drug (38).

Alternatively, Komrokji et al. (2018) highlighted the potential benefits of sotatercept for patients with limited treatment options. However, his study also reported a relatively high incidence of grade 3 - 4 TEAEs, affecting 34% of participants (39).

5.1. Strengths and Limitations

One of the strengths of the present study was the long follow-up period for patients, as well as the fact that all studies were conducted on humans. Additionally, the therapeutic effects of the drug on a common disease were investigated.

The first limitation of the study was the inability to examine the relationship between drug dosage and disease severity or reported outcomes. Second, the timing of adverse event occurrences was not mentioned. In all cases, the duration of adverse effects and how they were controlled or the development of drug tolerance were not addressed. Additionally, dose variability and small sample sizes in individual studies can affect the interpretation of adverse event data.

Third, full-text access to all articles was not available, and due to incomplete reporting of findings in some areas, it was not possible to conduct a robust meta-analysis. Therefore, it is essential to recognize that the results of this systematic review are based on a limited pool of data, which may have restricted generalizability and may not be fully representative of the broader PAH population.

5.2. Conclusions

According to the results of the current review study, treatment with sotatercept reduces PVR in patients with PAH. Improvements in 6MWD and NT-proBNP levels were also observed. Reported adverse effects were manageable and not serious. Future research could investigate the potential synergistic effects of combining sotatercept with other drugs to enhance its efficacy. Further studies involving larger populations are essential to thoroughly evaluate the efficacy and safety of sotatercept in patients with PAH. Additionally, exploring the potential of sotatercept in combination therapy could provide valuable insights into its effectiveness when used alongside existing treatments, thereby enhancing patient outcomes in challenging conditions.