1. Introduction

Stroke is a significant health concern and remains one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide (1). Hemodynamic compromise caused by carotid artery stenosis is a potential cause of extracranial stroke (2). The severity of carotid stenosis is a crucial parameter in medical or surgical treatments (3, 4) and can be estimated based on changes in flow velocities using Duplex ultrasound (5). Flow velocity thresholds are well-established for grading stenosis of the internal carotid artery (ICA) (6); however, little attention is given to concurrent changes in non-diseased extracranial arteries [i.e., the common carotid artery (CCA), external carotid artery (ECA), and vertebral artery (VA)]. Here, we present the case study of a patient with severe unilateral carotid stenosis, with a focus on alterations in blood flow velocities in the non-diseased ipsilateral and contralateral extracranial arteries, measured using Duplex ultrasound.

2. Case Presentation

A 63-year-old man with a history of hypertension and diabetes was referred to our vascular laboratory for a carotid ultrasound examination. One week prior to admission, the patient experienced intermittent limb weakness, aphasia, and dizziness, with no history of recent trauma or syncopal episodes. On the day of hospital admission these symptoms worsened, prompting evaluation in the emergency department. The patient described a significant impact on his daily activities and quality of life, with the uncertainty surrounding his symptoms causing considerable emotional distress and anxiety.

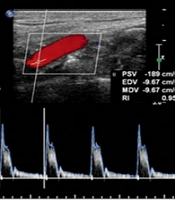

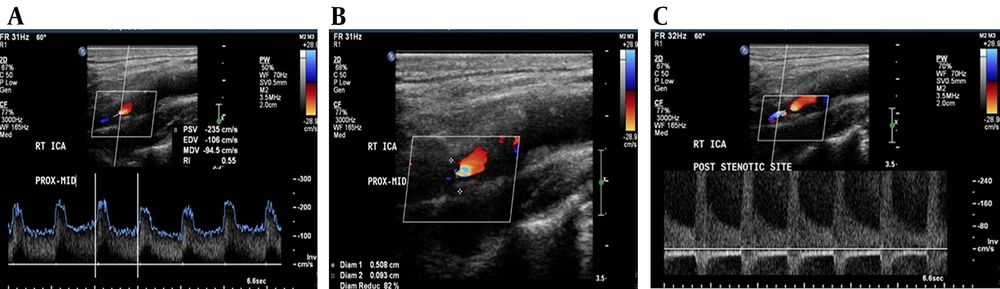

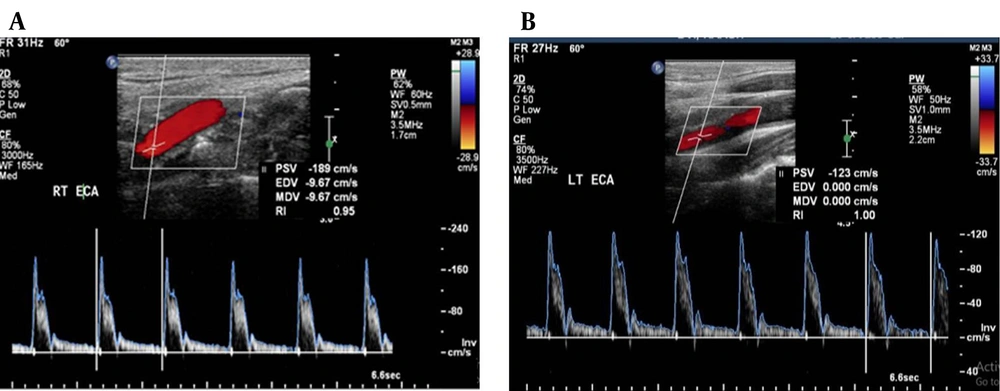

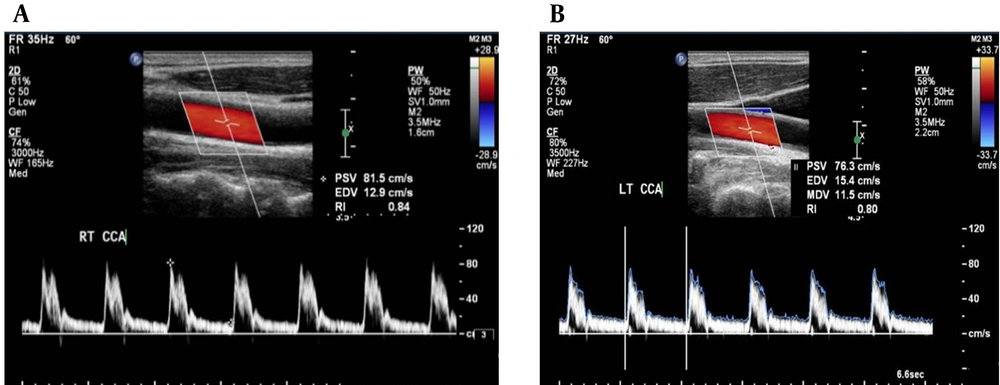

Total cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol were 4.43 mmol/L, 5.15 mmol/L, 2.42 mmol/L, and 0.64 mmol/L, respectively. CT brain imaging revealed no evidence of acute infarction or hemorrhage. Duplex ultrasound examination revealed > 70% right ICA stenosis with a peak systolic velocity (PSV) of 235 cm/s and an end-diastolic velocity (EDV) of 106 cm/s at the stenotic site (Figure 1A, B), and turbulent post-stenotic flow (Figure 1C) caused by an atherosclerotic plaque with low-level echogenicity. Vessels on the right side are considered ipsilateral to the stenosis, while vessels on the left side are contralateral to the stenosed right ICA. The ipsilateral ECA had a PSV of 189 cm/s (Figure 2A), which was 66 cm/s higher (+53.66%) than the contralateral ECA, which had a PSV of 123 cm/s (Figure 2B). Similarly, the ipsilateral VA had a PSV of 145 cm/s (Figure 3A), showing a 22 cm/s increase (+17.24%) compared to the contralateral VA, which had a PSV of 120 cm/s (Figure 3B). Additionally, the ipsilateral CCA had a PSV of 81.5 cm/s (Figure 4A), 5.2 cm/s higher (+6.38%) than the contralateral CCA, which had a PSV of 76.3 cm/s (Figure 4B). A PSV difference of ≈ 20 cm/s or more between corresponding arteries may indicate compensatory flow changes and vascular adaptation. These findings indicate a compensatory increase in flow velocity in the ipsilateral extracranial arteries in response to severe ICA stenosis.

The patient was treated with antiplatelet agents (aspirin and clopidogrel) and statins to mitigate stroke risk and prevent disease progression. While carotid endarterectomy or stenting can be beneficial in cases of severe ICA stenosis, the patient was not deemed fit for surgical intervention due to his overall condition and anesthetic risk. The patient is monitored at regular follow-ups to track disease progression and reassess intervention if necessary.

The study was conducted in full compliance with ethical standards protecting patient confidentiality. Verbal informed consent was obtained from the patient before inclusion in this case report. The study received ethical approval from the Unit of Biomedical Ethics Research Committee at King Abdulaziz University (reference No: 584-21).

3. Discussion

The case presented highlights the importance of assessing flow velocities in non-diseased extracranial arteries in individuals with ICA stenosis. Our patient had a severe right ICA stenosis, and we observed a significant increase in the peak systolic velocity of the ipsilateral external carotid and vertebral arteries compared to the contralateral side. The increase in flow velocities observed in our patient is likely due to hemodynamic compensation in response to the compromised blood flow caused by the stenosis. A previous study evaluated the effect of unilateral ICA occlusion on blood flow velocities in the VAs and reported an increase in peak systolic velocity in both the ipsilateral and contralateral VAs (7). These suggest that the severity of stenosis and occlusion of an ICA may have different effects on the hemodynamics of non-diseased extracranial arteries. Thus, careful bilateral assessment of blood flow velocities in extracranial arteries may be an effective method for monitoring patients with severe extracranial artery disease, especially in cases where the patient has a short neck or high carotid bifurcation. In such cases, where stenosis may not be fully depicted through ultrasound imaging, further evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging and/or computed tomography is recommended.

Assessing flow velocities in non-diseased extracranial arteries may provide additional information on the hemodynamic consequences of carotid artery stenosis and occlusion. The increase in flow velocities observed in our patient suggests an increase in blood flow in the ipsilateral external carotid and vertebral arteries, which may be indicative of increased collateral blood flow (8). This finding may have important clinical implications in the management of patients with carotid stenosis, as it suggests that non-diseased extracranial arteries may play a compensatory role in maintaining blood flow to the brain (9). It is worth noting that the increase in flow velocities observed in the ipsilateral CCA was minimal, with a difference of only 5.2 cm/s compared to the contralateral side. This finding suggests that the hemodynamic compensation in response to ICA stenosis may be more pronounced in the distal extracranial arteries. While this adaptation may initially reduce the risk of ischemic stroke, long-term hemodynamic instability could increase the risk of cerebrovascular events (10, 11). Additionally, chronic redistribution of cerebral blood flow may contribute to silent infarcts and cognitive decline over time (12, 13). Given these implications, risk stratification is essential for optimizing patient management and determining the need for early intervention (14). Furthermore, differential diagnosis of symptoms caused by severe atherosclerotic stenosis of the ICA should also be considered, including carotid dissection, embolic stroke, intracranial atherosclerosis, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, and vasculities (15-19).

As a single-case study, the findings primarily reflect individual hemodynamic adaptations to severe ICA stenosis and may not be applicable to all patients with similar pathology. Variability in collateral circulation, comorbid conditions, and disease progression may significantly influence hemodynamic responses and clinical outcomes between patients (20). Additionally, the findings are based on Doppler ultrasound, an imaging mode with limited capacity for detecting microvascular compensatory changes. These could be further elucidated using advanced imaging techniques (21). In conclusion, our case highlights the importance of assessing flow velocities in non-diseased extracranial arteries in individuals with ICA stenosis. The increase in flow velocities observed in non-diseased extracranial arteries suggests that they may play a compensatory role in maintaining blood flow to the brain.