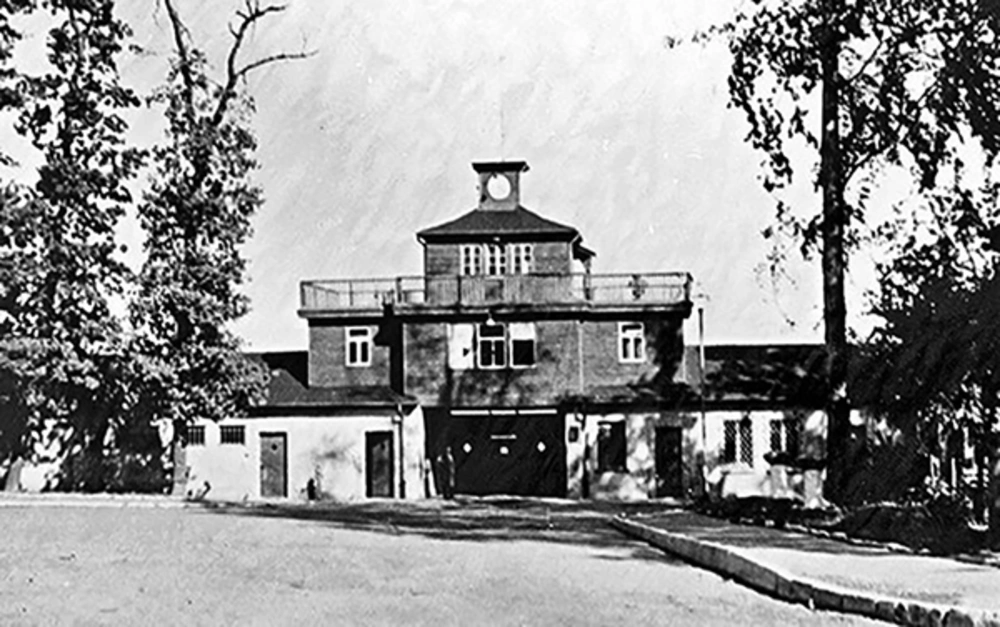

After the Second World War, in May 1945, the Soviet secret service, the NKVD (Narodniy komissariat vnutrennij del), began the construction of 10 special camps on German territory, formally integrated in 1948 into the Gulag Soviet prison system founded in 1923 (1). Between August 1945 and February 1950, the former Nazi concentration camp of Buchenwald was turned into the Soviet Special Camp Number 2. The individuals held at this camp were real or perceived opponents of the Soviet system; some were imprisoned after being sentenced by Soviet military tribunals, others without trial, including Nazi functionaries, officers of the Wehrmacht, and political prisoners. In the first month that Special Camp Number 2 was established, a total of 1392 individuals interned there. During its five years of operation, 28455 prisoners were held (2). The camp was closed in March 1950 and demolished in October of the same year when the majority of prisoners were sent to East German prisons and other inmates were released.

We calculate the mortality rate among prisoners in Special Camp Number 2 as 3.76% over five years, since a total of 7113 prisoners died there according to the Soviet records (2, 3), which represents a similar mortality than in Soviet gulag camps and labor colonies in the same years (5.95% versus 5.08% in Buchenwald in 1945 and 0.95% versus 0.72% in Buchenwald in 1950) (4). This data may be not entirely accurate, due to the fact that camp inmates were permitted no contact with the outside world, however, relatively real data are available. Soviet special camps were different from camps in the Soviet Union and were not labor camps. At the same time, reasons for inmate mortality are likely similar. In the special camps, there were hunger and cold, most of the barracks were overfilled, and insufficient hygiene, sanitation, and nutrition lead to illness and epidemics (5).

The medical system run in Gulags for decades was already exported to camps created in German territory after the end of the war. Among the Soviet troops were doctors employed to care for the system’s staff and for the medical and surgical needs of the prisoners. At the same time, the camps also employed prisoner - physicians. In every Soviet camp, as in every Gulag, there existed a sanitary unit equipped with a barrack called Stationary where a physician worked with his staff (6).

Archival documents regarding the Soviet period have been partially declassified recently. We have consulted and reviewed the archives of Buchenwald concentration camp, which was also the site of Special Soviet Camp Number 2 after the end of the Second World War, for the first time in relation to psychiatric care. The archive contains some data on the topic, which we will relate to the literature and discuss.

In Buchenwald Soviet Special Camp, the medical complex included a kitchen, a disinfection area and five main clinics: one each for surgery (I), internal medicine (II), and otorhinolaryngology (III). There also existed a clinic for dentistry and one specifically for women. Other sections were created, including a psychiatric station (VIIc). Under a chief medical officer for the camp, the majority of doctors on staff were German prisoners. In some cases specialists in one field were working in different fields: for example one otorhinolaryngologist was working in the women’s clinic, while the Otorhinolaryngologist section (III) was staffed by other otorhinolaryngologist. Supplies of medical drugs were insufficient and doctors had few options disposable to treat all kind of pathologies. As the single psychotropic drug, an antiepileptic was available. Epileptic patients were held with other inmates were considered invalids, such as blind people, however, not at the Psychiatric Station.

Psychiatric patients were held in the barrack that housed station VIIc. A specialist in neuropsychiatry was the doctor in charge of the Psychiatric Station. A nurse who provided care, but did not administer any drugs, attended them. Patients could not receive visits from their relatives. This, together with the lack of pharmaceutical treatment, made their pathologies worse in many cases. At the beginning of 1948, there were 14 psychiatric patients interned. In January 1949, the General Mayor in charge of the camp gave the order to send 31 registered psychiatric patients to ordinary German hospitals to receive treatment. At this point, the category of “mental - illness inmate” was officially eliminated. Regardless, in February 1949 there were still 19 prisoners registered as being held in the psychiatric station. Another file from June 1949 recorded that 62 inmates suffering from mental illness had to be vaccinated. The cases noted at this time included less severe forms of psychiatric illness than those noted before January of the year. Suicide was not common in the Soviet Special Camp at Buchenwald, as in other Soviet Special camps, such as Sachsenhausen (7), and the few reported cases occurred in places out of the barracks and none in the Psychiatric Station (Arkiv der Gedenkstatte Buchenwald).

The existence of psychiatric stations in postwar Soviet camps in Germany indicates the importance this medical specialty had to Soviet authorities. Starting after the end of World War II and increasingly since the early 1960s, Soviet authorities used psychiatric hospitals for the internment of political dissidents and persons exhibiting social behaviors that were unacceptable to the regime (8, 9). Collaboration between state-run psychiatric institutions, the police, and military officials are amply documented (10). In many cases detainees were falsely diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, confined in institutions that could be considered as “psychiatric prisons” and classified as a “psikhuskha” (psychiatric prisoner). No possibility to appeal the diagnosis and confinement existed for those patient - prisoners (8, 9). They were subjected to numerous humiliations, like sharing spaces with dangerous criminals and violent mental patients. They were also given overdoses of different psychotropic drugs (neuroleptics, barbiturates or psychotomimetic agents) for punitive purposes (11). In this framework of government - endorsed abuse, some prestigious psychiatrists actively participated.

This contribution discussed archival findings in the context of medical treatment at Soviet Special Camp in Buchenwald from 1945 to 1950. Further research on other Soviet Special Camps in Germany is needed to conclusively compare the role of medical care in general and psychiatric care, in particular other camp and prison contexts.