1. Background

Chronic pain is recognized as an important public health concern that poses significant economic and social problems (1). Pain provides the most common physical symptoms in primary care. It is considered a huge burden of suffering and discomfort for patients that reduces the quality of life (QOL), causes social disability, reduces health care, and causes substantial social and economic costs (2). In addition to deteriorating QOL, the literature shows that long-term pain leads to comorbidity of mental and physical diseases (3). Despite numerous physical and psychological problems that patients with chronic pain face, researchers believe that adaptation to disease and its acceptance are essential in the disease treatment and can affect individuals’ psychical and social conditions (4). Adaptation to disease refers to maintaining a positive attitude toward the disease and the world with many problems. Psychological adaptation includes seven subscales: attitudes toward work environment, family environment, illness, development of family relationships, social environment, and psychological disorders in sexual relations. Studies have shown that the strongest predictor of health services compared to other variables is psychological adaptation. However, nonadaptation to disease is characterized by anxiety, depression, helplessness, and behavioral problems (5). Chronic pain affects the patient and their family and social life (1). As the quality of marital relationships is somewhat correlated with physical health (6), researchers define marital relationships’ quality as a subjective and global assessment of the relationship and related behaviors (7). The quality of marital relationships is a multidimensional concept and includes various marital relationships such as adaptation, satisfaction, happiness, cohesion, and commitment. Expressing high satisfaction with the relationship, having positive attitudes toward the spouse, and low levels of hostility and negative behaviors indicate a desirable marital quality. Studies show that marital relationships’ quality affects individuals’ physical health status and occurrence of myocardial infarction, metabolic syndrome, and mortality (8). A review of the literature shows that high-quality marriages directly affect psychological well-being and may play an influential role in subsequent stressors in life, such as caring for a partner with a disease (9). Providing care for a sick spouse affects the caregiver in a variety of ways and may have adverse effects on personal interests, social life, QOL, and psychological status (10). Researchers believe that good marital relationships are the basis of good family functioning, and if the family base is not sufficiently strong, it causes divorce and thus physical and mental problems (11). Preliminary reports on the family life of the patient with chronic pain have shown that they often face widespread marital and sexual problems (12). Sexual issues are among the most crucial issues in married life, and adaptation in sexual relations is considered an element affecting happiness (13). One of the hot topics in sexual relations is sexual self-esteem, which is one of the dimensions of public self-esteem and refers to individuals’ emotional response to their thoughts, feelings, and sexual behaviors (14). Numerous studies have shown that chronic illnesses and diseases can lead to reduced marital adjustment and sexual, emotional, and communication problems between couples (15, 16).

When sexual self-esteem is impaired, life satisfaction, the ability to experience pleasure, interaction with others, and the ability to form intimate relationships with others are damaged. If damage to sexual self-esteem is severe, it can cause severe dysfunction (17). In other words, sexual self-esteem and subsequent sexual satisfaction affect both the quality of married life and the individual’s overall health in various dimensions. Researchers have shown that dissatisfactory sex and the resulting physical and psychological stress disrupt health care and reduce capabilities, abilities, and creativity (18). Therefore, sexual self-esteem, directly and indirectly, affects individuals’ physical, psychological, and social health. Considering the importance of marital quality and its impact on various aspects of women’s lives, especially sexual self-esteem, an attempt has been made to explain the role of marital and sexual variables in women’s psychological adaptation to disease in patients with chronic pain. Since less research in Iran has focused on the importance of marital relationships and sex variables in these patients, this study investigated whether sexual self-esteem could mediate the relationship between marital quality and psychological adaptation to disease in women with chronic pain.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the mediating role of sexual self-esteem in the relationship between marital quality and psychological adaptation to disease in women with chronic pain.

3. Methods

This descriptive-analytic study of correlation type was conducted on 200 women with chronic pain admitted to orthopedic centers in Ardabil City, Iran. The patients were selected using the available sampling method. The inclusion criteria were Iranian nationality, an Ardabil resident, married status, chronic pain, low education literacy, and willingness to participate. The study was performed under the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Administration of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili. We explained the research objectives to the participants, and they were assured of their information confidentiality. Eligible participants completed the informed consent form. The participants could withdraw the research at any time, and the research was performed based on respecting the participants’ rights by ensuring anonymity and confidentiality.

3.1. Data Collection Tools

The Marital Quality scale: Busby et al. developed a revised version of the scale in 1995 to measure marital relationship quality. The scale consists of 14 items and three subscales of agreement (six questions), satisfaction (five questions), and cohesion (three questions) which show a total score of marital quality. High scores on the scale indicate high marital quality. The scale’s main version has 32 items made by Spinner based on Levies and Spinner’s marital quality theory (19). The revised version was used in this research. The items in the scale are scored based on a 6-point Likert scale (always have a difference = 0 and have a permanent agreement = 5). Using Cronbach’s alpha, Holist and Miller reported the reliability of 0.79, 0.80, and 0.90 (19) for the three subscales of agreement, satisfaction, and cohesion, respectively. Yousefi (20) reported that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the entire scale equals 0.70.

3.1.1. The Psychological Adaptation Questionnaire

Leonardo Drogatis designed this questionnaire in 1990 to examine psychological adaptation to chronic illness. This questionnaire includes 34 items and five subscales: attitude toward illness (8), family environment (8), sexual relations (6), development of family relationships (5), and psychological disorders (7). In this study, items are scored based on the 4-point Likert scale, with 0 = at all, 1 = slightly, 2 = to some extent, and 3 = completely. The sum of each component’s scores was divided by the number of that component’s items, with the average being that component’s adaptation score. The sum of the total scores was divided by the total number of items. The total mean was considered as the total adaptation score. Feghhi et al. (21) first translated the questionnaire. After making changes, 10 experts examined the validity of the questionnaire. Moreover, the questionnaire was distributed among 20 patients with type 2 diabetes, and its reliability was reported 0.94 using Cronbach’s alpha (21).

3.1.2. The Women’s Sexual Self-esteem Questionnaire

Zinah and Schwarz developed this questionnaire in 1996, and Karami et al. (11) translated it into Persian. The questionnaire includes 81 items measuring women’s emotional responses to their sexual thoughts, feelings, and behaviors and five subscales of skill and experience, attractiveness, control, ethical judgment, and adaptability. The items of the questionnaire are scored based on a 6-point Likert scale, with high scores indicating high sexual self-esteem. Several studies have reported this tool’s reliability to be between 0.84 and 0.90 by calculating Cronbach’s alpha (11).

The collected data were analyzed in SPSS 25 and Amos 24 software. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation), Pearson’s correlation coefficient with the significance level of P < 0.001, and multiple linear regression analysis.

4. Results

Based on the descriptive demographic variables’ results, the mean age of the respondents was 33.37 ± 9.09 years. Of these, 179 (89.5%) had children, and 21 (10.5%) had no children. Regarding education, 17% of the respondents had undergraduate education, 54.5% had a diploma and postgraduate education, 18.5% had bachelor’s degree, and 10% had master’s degree and above.

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics (mean and standard deviation) and indicators of the shape of the distribution of scores (skewness and elongation) for each variable.

| Variable | Mean ± SD | Minimum | Maximum | Skewness | Elongation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital quality | 58.68 ± 7.68 | 18 | 64 | 0.42 | 0.19 |

| Psychological adaptation | 123.53 ± 17.74 | 32 | 160 | 0.19 | 0.79 |

| Sexual self-esteem | 213.79 ± 36.68 | 103 | 395 | 0.17 | 0.52 |

As shown in Table 2, there was a significant positive relationship between the exogenous variable of marital quality and the primary dependent variable of psychological adaptation at the level of 0.01. There was also a significant positive relationship between the intermediate dependent variable of sexual self-esteem and the primary dependent variable of psychological adaptation at the level of 0.01. Moreover, there was a significant positive correlation between the exogenous variable of marital quality and the intermediate dependent variable of sexual self-esteem at the level of 0.01. The highest correlation coefficient was related to the relationship between sexual self-esteem and psychological adaptation.

As shown in Table 3, in the first step, the predictor variables were entered into regression analysis. These results showed that marital quality with an impact factor of 0.49 at the level of P < 0.01 was able to predict 0.24 of changes in psychological adaptation (Table 3). In the second step, the sexual self-esteem variable as a criterion variable and the marital quality variable as a predictor variable obtained from the first stage were entered into regression analysis. The results showed that marital quality with an impact factor of 0.48 at the level of P < 0.99 was able to predict 0.23 of changes in sexual self-esteem (Table 3).

| Level | Variable | β1 | T | Significant Level | R | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Quality of married life | 0.49 | 8.02 | 0.01 | 0.49 | 0.24 |

| Second | Quality of married life | 0.48 | 7.25 | 0.01 | 0.48 | 0.23 |

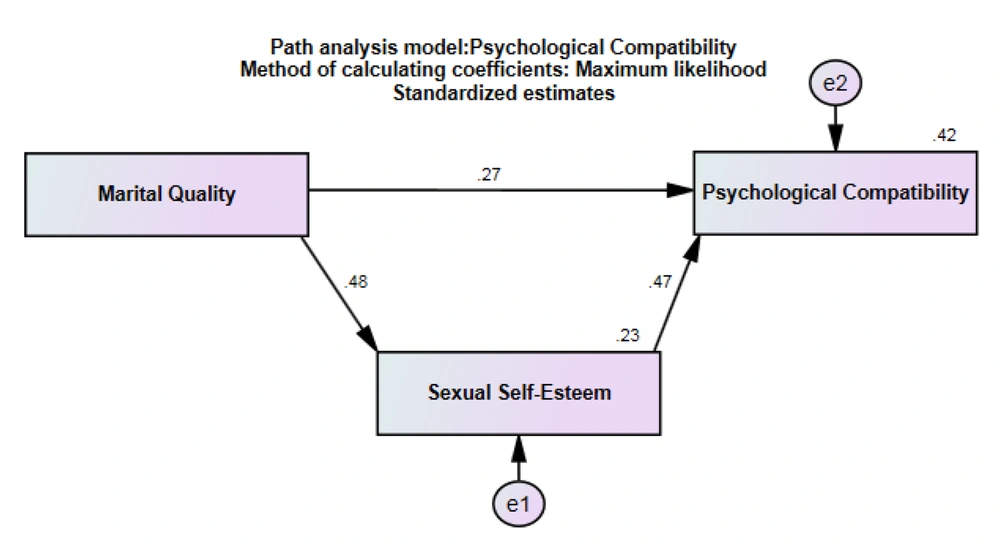

As shown in Table 4, the upper and lower limits of the sexual self-esteem variable did not include the relationship between marital quality and psychological adaptation. This variable mentions the mediating role in the relationship between these two variables. Also, the predictor and mediator variables could predict 42% of psychological adaptation changes, which is moderate (Figure 1).

| Variables | β | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial indirect effect dissociative | ||||

| Marital quality → sexual self-esteem → psychological adaptation | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.010 |

| Standard indirect effect | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.015 |

Based on the above significant relationships, the mediating role of sexual self-esteem was investigated using path analysis with SPSS software and the Andrew Hayes program. According to this hypothesis, marital quality was considered an exogenous or independent variable, sexual self-esteem an intermediate dependent variable, and psychological adaptation a final dependent variable or endogenous variable (Figure 1).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between marital quality and psychological adaptation to disease with the mediating role of sexual self-esteem in women with chronic pain. The results showed that marital quality had a significant positive relationship with psychological adaptation to disease in women with chronic pain. The results agree with the previous findings, showing that marital quality positively correlates with psychological adaptation to disease (22). A structural model also confirmed the relationship between QOL and psychological adaptation to chronic illness and disability (23).

Based on this research’s findings, it is important to point out that, according to researchers, QOL has many different physical, psychological, and social dimensions (24). Therefore, women with chronic pain who experience high-quality marital relationships, due to gaining a sense of satisfaction in the family environment, find a positive feeling about themselves and others, which increases with the psychological and social well-being. In confirmation of the above, studies have shown that a close and intimate relationship has a vital role in emotional and physical well-being and affects the overall quality of happiness and satisfaction with life (25). It can be stated that eligible marital quality, along with emotional support, increases hope in these women to follow the treatment process and achieve positive treatment results. Thus, women with chronic pain, if having emotional support from their husbands and experiencing less marital stress, focus more on improving their mental and social functioning, physical condition, and performance in other aspects of life.

In this regard, previous studies show that patients’ access to various sources of support reduces emotional helplessness and inability to cope with pain, reduces patients’ negative emotions and anxiety, and increases their ability to cope with disease. Providing support also improves these individuals’ overall performance and thus increases psychological adaptation in them (17).

The other finding of the present study indicated that sexual self-esteem, while having a positive relationship with psychological adaptation in women with chronic pain, can mediate a positive relationship between marital quality with psychological adaptation. This finding is consistent with the results of other similar studies, showing that self-esteem has a significant positive relationship with psychological adaptation (26). Other related studies have shown that self-esteem and interpersonal relationships are positively correlated (27).

According to the above findings, it can be mentioned that high marital quality can increase marital intimacy and satisfaction and, as a result, can increase sexual self-esteem in women with chronic pain. Moreover, high marital quality and intimacy between couples help them meet their psychological and emotional needs and desires within the marital relationship framework and thus help women with chronic pain feel positive about themselves. Therefore, high sexual self-esteem resulting from the desirable marital quality helps women with chronic pain have a positive view about themselves and their marital abilities and also an optimistic view about others; it also helps them increase psychological and social adaptation to chronic pain. In support of this, researchers believe that people who are more adaptable are more optimistic about themselves and others, more focus on their life priorities, have more intimate family relationships, better cope with their physical conditions, have higher physical activities, are more optimistic about their illness, and experience faster recovery than their less adaptable counterparts (17).

This study had some limitations. It was a cross-sectional study that assessed the participants using a self-report scale that might not be sufficient for collecting accurate data. The correlation between the variables may be due to other variables, which can only be controlled by the survey of each variable’s role in creating such variables. Further, since the present study was performed among women with chronic pain as Ardabil residents, caution should be exercised in generalizing the findings to other cities.

5.1. Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the mediating role of sexual self-esteem in the relationship between marital quality and psychological adaptation in women with chronic pain. The results showed that in addition to a positive relationship between the marital quality and psychological adaptation to disease in women with chronic pain, sexual self-esteem could play a fully mediating role in the relationship between these two variables. Therefore, according to the present study’s findings and by considering the literature on the variables, it can be concluded that high marital quality helps provide psychological and emotional needs of women with chronic pain such as sexual needs and thus increases their sexual self-esteem and psychological adaptation to chronic pain.