1. Background

In the latest version of the DSM5 (Fifth Edition), bipolar disorder is considered an independent disorder (1, 2), which is influenced by family history and genetics as well as seasons (3). Bipolar disorder, as a chronic illness, is also known as periodic dementia with complications, such as poor economic status, unemployment, dismissal, marital disputes, lack of continuing education, and multiple hospitalizations in psychiatric centers (4).

Bipolar disorder type I is characterized by episodes of mania with or without depression (5), so sometimes patients develop depression or periods of mania (6). Although the exact cause of these disorders has not been determined yet, possible causative factors are hereditary, time of birth, and external factors such as infection (7). Structure neuroimaging techniques suggest that parts of the brain may be involved in patients with mania (8). In this disorder, the patient suffers from individual and social dysfunction. Thus, type 1 bipolar disorder can be classified as one of the chronic mental disorders that, in addition to functional decline, can also affect interpersonal interactions and quality of life (9). It has also been shown as the sixth most debilitating mental disorder worldwide (10), with a global prevalence of 2.4% (11) and 1% in Iran (12). Therefore, bipolar disorder type 1(BID) is a common, chronic, and recurrent disease. Only 7% of all patients are asymptomatic, while 45% of patients experience more than one recurrence, and 40% experience the chronic type of the disease (13).

Due to the destructive effects of this disease on individual and social relationships and the quality of life of patients, effective treatment has been a mental concern for many years (14). Despite the effectiveness of the treatment process, which is often carried out in a controlled and precise manner during hospital stays, the lack of patient cooperation in continuing the treatment after discharge can lead to the development of symptoms and recurrence of the disorder. This, in turn, may result in the patient being referred back to the hospital, creating a vicious cycle of rehospitalization (15). In this regard, post-discharge follow-up is considered an important issue that links the coherence of inpatient and post-hospital conditions. Following the course of the disease and paying attention to the patient’s condition after discharge can improve the medical system, prevent rehospitalization of patients, and impose additional costs on the government and family (16).

Researchers believe that providing a codified follow-up program is the best method to treat patients and emphasize that, in most cases, the patient does not fully understand the importance of post-discharge training and follow-up (17, 18). Therefore, in order to reduce the complications of the disease after discharge and prevent the recurrence of the disease, it is better to train and follow the patient after discharge (19). During follow-ups, potential and actual problems of the patient can be found by the treatment and care team, which provides an opportunity to use the right method to manage the disease. However, the care and training should be repeated periodically and consistently, and it should be specified how long it should be done again (20). These follow-up programs may be considered 3 to 6 months after discharge, and sometimes they are longer (21). To effectively plan post-discharge care, it is important to establish a time frame to assess the long-term impact of the home care plan and determine if any additional care is needed (22, 23). The results of a one-year follow-up study on 31 patients with consecutive bipolar disorder showed that the severity of the patient’s symptoms improved significantly only at the time of discharge and did not markedly change after discharge (24).

In a six-month study on 13 patients with the first episode of mania, it was found that 54% of patients continued their treatment and followed medication after three months, but this rate decreased to 38% in the sixth month (25). Also, during 17 months of follow-up in patients with mania diagnosed with type 1 bipolar disorder, 40.9% of patients recurred (26). It seems that these recurrences were due to the lack of continuing the patient care program after discharge (27).

Following home nursing care will strengthen family care as well as maintain patient independence (28). On the other hand, due to the nature of psychiatric diseases and the existence of recurrent periods in this type of disorder, home nursing care can be considered a suitable solution to maintain the quality of the treatment after home care (29). Home nursing care services in the first phase of this study immediately after the intervention caused a reduction in the severity of symptoms in type 1 bipolar patients (30), but its effect in the second phase of the study, which was a 6-month follow-up, was not known to the researchers. On the other hand, the studies were conducted mostly on psychotic patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, and in limited studies, post-discharge follow-up was also conducted for mood patients. Thus, this study investigated the symptoms of patients with BID after home care in a 6-month follow-up.

2. Objectives

The objective of this study was to examine the duration of the effect of nursing home care on patients with type 1 bipolar disorder during the follow-up period.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This study is part of a clinical trial designed and conducted in two phases, and this article presents the result of the second phase.

3.2. Participants and Setting

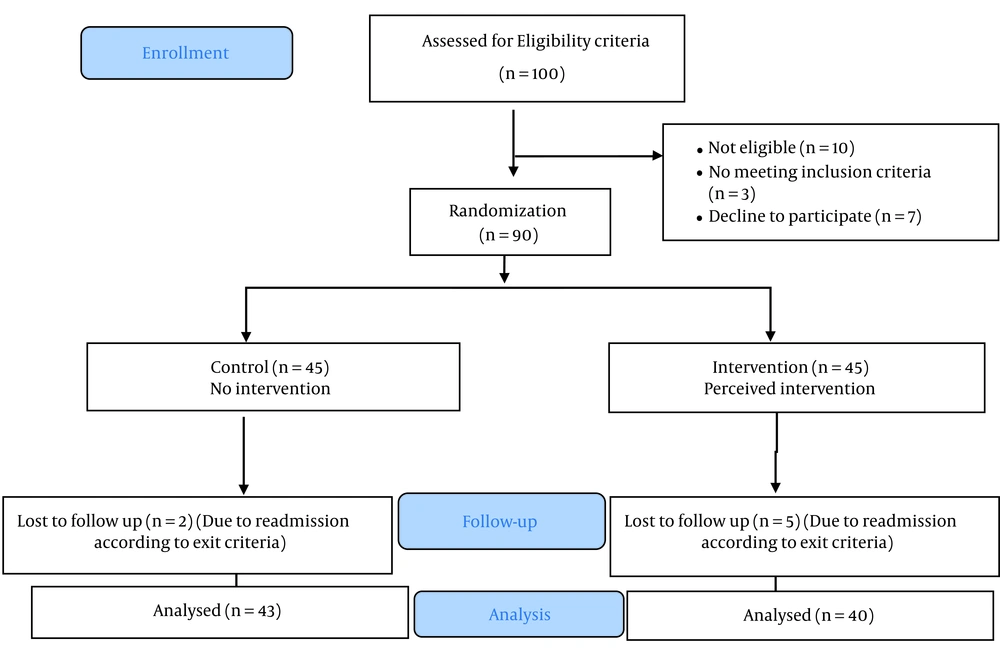

In the first phase, an intervention was conducted on 100 people who volunteered to participate in the research. However, based on the inclusion criteria, only 90 individuals were deemed eligible and were subsequently divided into two groups: The intervention group and the control group. Thus, 45 people were assigned to each group (Figure 1). After three months, the intervention, which involved receiving nursing care at home after discharge, was analyzed. The details of the intervention are described below. Following the analysis, the study entered its second phase, which involved a 6-month follow-up period to track the results of the intervention. The statistical population of this study consisted of type 1 bipolar patients at 22nd Bahman Hospital in Qazvin in 2019. The sample size was estimated at 37 people in each group, considering a similar study with an average effect size of 0.25, a type 1 error of 0.05, and a power of 0.80 (31). However, this was increased to 45 people in each group due to the possible attrition of 20%. Inclusion criteria consisted of patients with mania in a psychiatric hospital in Qazvin aged at least 18 years. Rehospitalization and participation in similar programs were considered exclusion criteria.

3.3. Intervention

A total of 90 patients who were selected by the convenience sampling method were divided into two experimental and control groups by randomly assigning 15 blocks of six. In this study, in order to hide the random allocation process, the names of the groups were placed in envelopes, numbered from one to 90, and placed in a packet. For the intervention group, the package designed for nursing care was implemented at home, and for the control group, this nursing care was not performed, and the researchers did not intervene in other routine treatment programs of the hospital performed for both groups. The home nursing care program included family support and education, patient support and education, mental health assessment in patients, access to basic mental health care, and promotion of the mental health of patients. The ethical code was IR.QUMS.REC.1398.192, and the IRCT code was IRCT20190928044911N1. The participation was voluntary, and the participants could leave the study if desired. They were also assured of the confidentiality of information and the accuracy and confidentiality in recording information and data obtained at data collection.

The research instruments included the Demographic Characteristics Questionnaire and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (1978). The YMRS scores range from 0 - 60, and a score of above 20 indicates a manic phase (32). Young’s questionnaire was created by Young in 1978. It has a concurrent validity of 0.96, inter-rater reliability of 0.92, and Cronbach’s alpha of 0.72. The results showed a reliability of 0.72 for the patient group and 0.62 for the normal group, while the inter-rater reliability was 0.96. Also, the validity coefficient of total scores and group membership (focal correlation) was 0.92, and the results of the validity analysis of the questions indicated the high power of all questions in differentiating the normal group from the patient group (33). Subjects were asked to complete the questionnaires before the intervention and then after three months. The patients were subjected to the intervention (home nursing care) by making two telephone calls every 15 days and holding meetings (30 - 45 min) with the patient and his/her family. At the end of three months, the patients completed the YMRS to assess the severity of symptoms, and the control group that did not receive the intervention also completed the questionnaire (the first phase of the study). Follow-up was then performed for six months after the intervention (the second phase of the study), during which no intervention was performed. The questionnaires were completed by subjects every month, and then the result was compared with before the follow-up (Figure 2). SPSS 24 software was used to analyze the data.

Sample size formula

F tests–ANOVA: Repeated measures between factors

Analysis: A priori: Compute required sample size

Input:Effect size f = 0.25

α err prob = 0.05

Power (1-β err prob) = 0.80

Number of groups = 2

Number of measurements = 8

Corr. among rep measures = 0.5

Output: Noncentrality parameter λ = 8.2222222

Critical F = 3.9738970

Numerator df = 1.0000000

Denominator df = 72.0000000

Total sample size = 74

Actual power = 0.807586

4. Results

The studied patients were examined for all quantitative and qualitative demographic variables, including age, sex, education, family history of mental illness, duration of illness, and the number of hospitalizations (Table 1). It was found that the two groups were homogenous regarding these factors (P < 0.05).

| Variables and Levels | Experimental Group | Control Group | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.362 | ||

| Female | 12 (30) | 17 (40) | |

| Male | 28 (70) | 25 (60) | |

| Education | 0.252 | ||

| Below diploma | 19 (47.5) | 27 (64.2) | |

| Diploma | 15 (37.5) | 9 (21.5) | |

| University | 6 (15) | 6 (14.3) | |

| Family history of mental illness | 0.176 | ||

| Yes | 15 (37.5) | 22 (52) | |

| No | 25 (62.5) | 20 (48) | |

| Quantitative variables | |||

| Age (y) | 38.75 ± 12. 91 | 41.53 ± 8.93 | 0.072 c |

| Duration of disease (mo) | 97.67 ± 99.71 | 130.62 ± 110.64 | 0.167 c |

| Number of hospitalizations | 3.22 ± 3.12 | 4.62 ± 5.62 | 0.275 c |

a Values are presented as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b Chi-square test-Fisher Exact test.

c Mann Whitney U test.

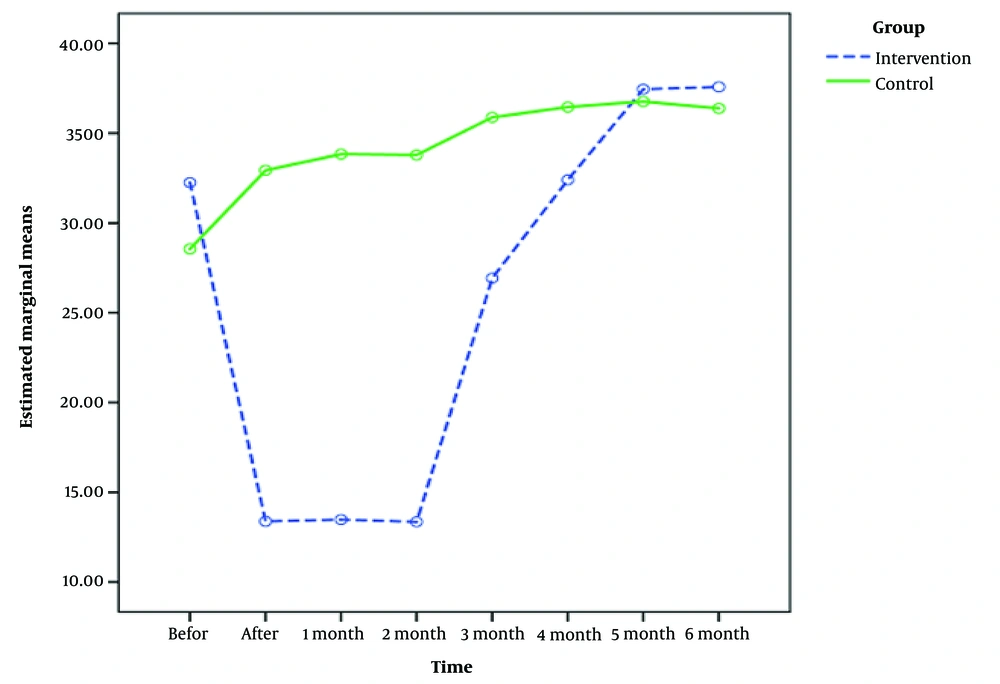

A comparison of the mean scores of the severity of symptoms is presented in Figure 2 and Table 2. Before the intervention, there was no difference between the two groups, but the difference was statistically significant after the intervention.

| Disease Severity | Experimental Group | Control Group | Significance Level (Independent t-Test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | 32. 25 ± 9.93 | 28. 54 ± 10.97 | 0.113 |

| After intervention | 13. 38 ± 5.16 | 32.9 ± 12.81 | < 0.001 |

| One month after the intervention | 13. 47 ± 4.92 | 33.83 ± 14.49 | < 0.001 |

| Two months after the intervention | 13. 35 ± 5.05 | 33.78 ± 14.48 | < 0.001 |

| Three months after the intervention | 26. 92 ± 9.92 | 35.88 ± 12.73 | 0.001 |

| Four months after the intervention | 32.4 ± 11.56 | 36.45 ± 12.59 | 0.134 |

| Five months after the intervention | 37.45 ± 10.65 | 36.76 ± 12.44 | 0.789 |

| Six months after the intervention | 37.57 ± 10.70 | 36.38 ± 12.58 | 0.646 |

| Result of repeated-measures ANOVA | F = 80.89, P < 0.001 | F = 12.43, P < 0.001 |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

Also, one, two, and three months after the intervention, the mean score of symptom severity was 13.47 ± 4.92, 13.35 ± 5.05, and 26.92 ± 9.92 in the experimental group and 33.83 ± 14.49, 33.78 ± 14.48, and 35.88 ± 12.73 in the control group, respectively. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant. In all three follow-ups, the mean score of symptom severity was lower in the experimental group than in the control group (P < 0.05).

Also, 4 months after the intervention, the mean score of disease severity was 32.4 ± 11.56 in the experimental group and 36.45 ± 12.59 in the control group. The experimental group had a lower mean score, but this difference was not statistically significant between the two groups (P < 0.05). At five and six months of follow-up, the mean score of symptom severity was slightly higher in the experimental group than in the control group (P < 0.05).

Also, the results of repeated-measures ANOVA showed a significant decrease in the severity of symptoms after the intervention. Until the second month of follow-up, almost the same mean severity scores were reported, but after the third month of follow-up, an increase was observed in the severity of symptoms, which was statistically significant (P < 0.001). However, in the control group, in general, there was an increasing trend in the severity of symptoms, which was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Tables 3 and 4 indicate the overall effect of time and group using repeated-measures ANOVA. The results showed that the effect of time, the interaction of time and group, and the effect of all three factors (time, interaction of time, and group) were found to be significant based on the significant value, test statistics, and partial eta squared. Therefore, the intervention had a significant effect (P < 0.001) on reducing the severity of symptoms. Also, the difference in the mean score of symptom severity in the follow-up showed a significant effect (Tables 3 and 4).

| Source | Mean Square | F | P-Value | Partial Eta Squared | Observed Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time effect | 2919.64 | 70.50 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.99 |

| Group *time effect | 2202.55 | 53.18 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.99 |

| Source | Mean Square | F | P-Value | Partial Eta Squared | Observed Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 593425.31 | 840.39 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.99 |

| Group effect | 11762.47 | 16.65 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.98 |

5. Discussion

Bipolar disorder is a reversible disease, and most patients experience recurrences throughout their lives if they do not receive proper treatment and follow-up. Each recurrence, in addition to unpleasant effects on the mental state of the patient and those living with them, also has a negative effect on the course of the disease. Also, the acute phase of the disease and its relapse impose high costs directly and indirectly on the family and society (34).

Navidian et al., in their clinical trial on the effect of family education on the psychological burden of home caregivers of mentally ill patients, showed that the mean psychological burden of caregivers of schizophrenic patients who received group training intervention was significantly reduced compared with the control group. As a result, the quality of life of mentally ill caregivers increased significantly (35). Hubbard et al. conducted a study in which short-term psychological interventions were considered for caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. According to their results, the training group, compared with the control group, showed a reduction in the psychological burden of caregivers and an increase in their knowledge about bipolar disorder and caregiver self-efficacy. These changes persisted at follow-up and after one month and then increased (36).

In a study to investigate the impact of critical time intervention on reducing psychiatric rehospitalization following hospital discharge, Tomita and Herman showed that at the end of the follow-up period, psychiatric rehospitalization was significantly lower in the group assigned to critical time intervention compared with the usual services group (37). Lee et al. showed that rehospitalization in patients was decreased (38). Pan et al., in their study on the effect of the frequency of three-year follow-up after discharge on treatment costs in discharged patients with bipolar disorder, showed that patients subjected to 13 - 17 postoperative visits paid the lowest costs for mental health services and health care (39). Roos et al. assessed the use of mental health services in patients with severe mental disorders in the first 12 months after discharge from a psychiatric hospital and showed that post-discharge mental health services reduced patients’ total use of medical services and costs without an increase in hospitalization rate (40).

Li et al. examined the recurrence and improvement of social functioning in discharged psychiatric patients with bipolar disorder. They found a significant difference in the recurrence of the disease after a follow-up in the first year after discharge and the first two years after discharge (41). Khaleghparast et al. showed that the discharge program can be effective in improving knowledge and reducing rehospitalization of patients with schizophrenia (42). The results of the mentioned studies are all consistent with the present study, indicating that follow-up after discharge in psychiatric patients reduces the recurrence of the disease and reduces the number of hospitalizations and costs.

In contrast, Amini et al. conducted a study assessing a follow-up of patients with mania. They showed that the severity of symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder decreased significantly during hospitalization; however, it did not change significantly during one year of follow-up (43). To explain this finding, it can be said that a follow-up of the patient after discharge can significantly reduce the number of hospitalizations. Sometimes, the patient does not understand the importance of post-discharge education. Thus, to reduce the complications of the disease in the post-discharge period, it is better to follow and train the patient seriously after discharge. During follow-up, the patient’s health problems can be detected by the care team, providing an opportunity to apply the correct method of patient management.

5.1. Limitation

The limitations of the study included the non-cooperation of patients and their families, possibly due to the nature of psychiatric disorders. In this regard, the possible benefits of the research, including the reduction of rehospitalization and, as a result, the reduction of costs, were explained to them.

5.2. Conclusions

The results of this study showed that a post-discharge care program for up to four months reduces the severity of symptoms in type 1 bipolar patients. Also, due to the special conditions of bipolar type 1 patients and the recurrent nature of the disease, repeating the home nursing care program at an appropriate time can help reduce the severity of symptoms in these patients, which cannot be achieved without repetition as well as follow-up. The periodic repetition of this care program at intervals of four months will maintain the improvements and reduce the severity of symptoms in these patients. Accordingly, the patient can return to the community faster and gain previous functioning, and finally, the number of hospitalizations is reduced. It is suggested that future research should investigate the impact of nursing care at home on the severity of symptoms of other psychiatric disorders, as well as on the recurrence rate of BID and the rate of patient rehospitalization.