1. Context

The family is the most crucial environment where the characteristics of men and women intersect (1). It is a place where relationships and interactions are more intense, deep, and expansive than anywhere else (2). However, violence against family members, particularly women, poses a significant social problem that threatens families in all human societies (3). Violence is defined as any behavior, whether action or omission, that aims to harm another person, both physically and mentally (4). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one in three women has experienced violence by their husbands or partners (5). In Europe, one in every ten women has experienced sexual violence since the age of fifteen, and one in every twenty has experienced rape. Shockingly, six million women in Europe have been raped since the age of fifteen (6).

In 2019, 13,370 cases of spousal abuse were recorded by social emergency centers in Iran. However, according to the Forensic Medicine Organization, only 9,500 cases of domestic violence were registered in Tehran province’s forensic centers that year, with statistics from other provinces also notable. A high percentage of domestic murders occur between couples (3). Violence can lead to chronic, destructive diseases and is associated with numerous short- and long-term mental and physical health consequences, including PTSD, mental health disabilities, physical syndromes, chronic pain, arthritis, migraines, hearing loss, angina pectoris, sexually transmitted infections, functional gastrointestinal disorders, and alterations in endocrine and immune function (7). Lifetime spousal physical violence significantly increases the odds of chronic conditions, physical illnesses, and health risk behaviors (8, 9). Additionally, several health risk behaviors, such as heavy drinking, recreational drug use, and HIV risk factors, have been linked to IPV.

Violence against women is a fundamental issue in the realm of human rights and public health worldwide. It poses a serious threat to societal and family foundations, as well as to women’s rights, health, well-being, and integrity (10). The roots of violence against women lie in values, social and cultural beliefs (11). In recent years, researchers and experts in social issues have increasingly focused on domestic violence against men (12). Violent and disruptive behaviors by women in the home environment can cause physical and mental harm to men and, in extreme cases, may even lead to death. Conversely, violent behavior by women can damage the family institution, causing serious harm to the family structure (13). Researchers have identified several social factors contributing to violence against family members. These include a lack of social support, spiritual and family values, and economic satisfaction (14). Other factors encompass acceptance of male authority, husband’s addiction, and society’s sexual attitudes towards women (15). These influences have contributed to rising divorce rates in society (16). According to the Forensic Medicine Organization, physical violence is the most common form of violence against women (17).

In a study by Kohestani and Alijani, 77.2% of participants faced at least one type of violence during quarantine. The research indicated that women experienced more than 91% psychological violence, over 65% physical violence, about 43% sexual violence, and nearly 39% of violence resulting in injury (18). Violence against women can have devastating consequences for society (19). According to the UK Office for National Statistics, 8.2% of women and 4.0% of men in England and Wales reported experiencing domestic violence (20).

2. Objectives

Given the rise in violence and its numerous adverse consequences, this study aimed to examine the prevalence of domestic violence in Iran through a systematic review and meta-analysis approach.

3. Methods

The present research is a systematic review and meta-analysis that examines the prevalence of domestic violence in Iran.

3.1. Search Strategy

The search strategy involved examining Persian and English articles in MagIran, SID, Google Scholar, Scopus, EMBASE, Web of Science, and PubMed databases using keywords such as “domestic violence,” “prevalence,” “spousal abuse,” “Iran,” “physical violence,” “mental violence,” “sexual violence,” or their Persian equivalents and combinations. The keyword combinations were combined with operators (AND, OR), and advanced searches were conducted. To obtain additional articles, the reference lists of selected articles were reviewed. The search for sources continued until March 2023 without any time restrictions. The search strategy for the PubMed database is as follows: [(Domestic Violence OR Family Violence OR mental violence OR physical violence OR sexual violence) AND (Prevalence)] AND [Iran[Affiliation)].

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies that examined the frequency or prevalence of domestic violence in Iran were included in the meta-analysis. Case-control and interventional studies were excluded due to insufficient data for analysis, and narrative reviews were omitted to avoid redundancy. Letters to the editor and poster-format abstracts were excluded because of lower quality. Articles in languages other than Farsi or English were excluded, as the search was conducted using only these languages. Studies without full texts or with incomplete abstract data were also excluded. Studies with insufficient quality in the qualitative evaluation phase or those focusing on populations outside Iran were excluded.

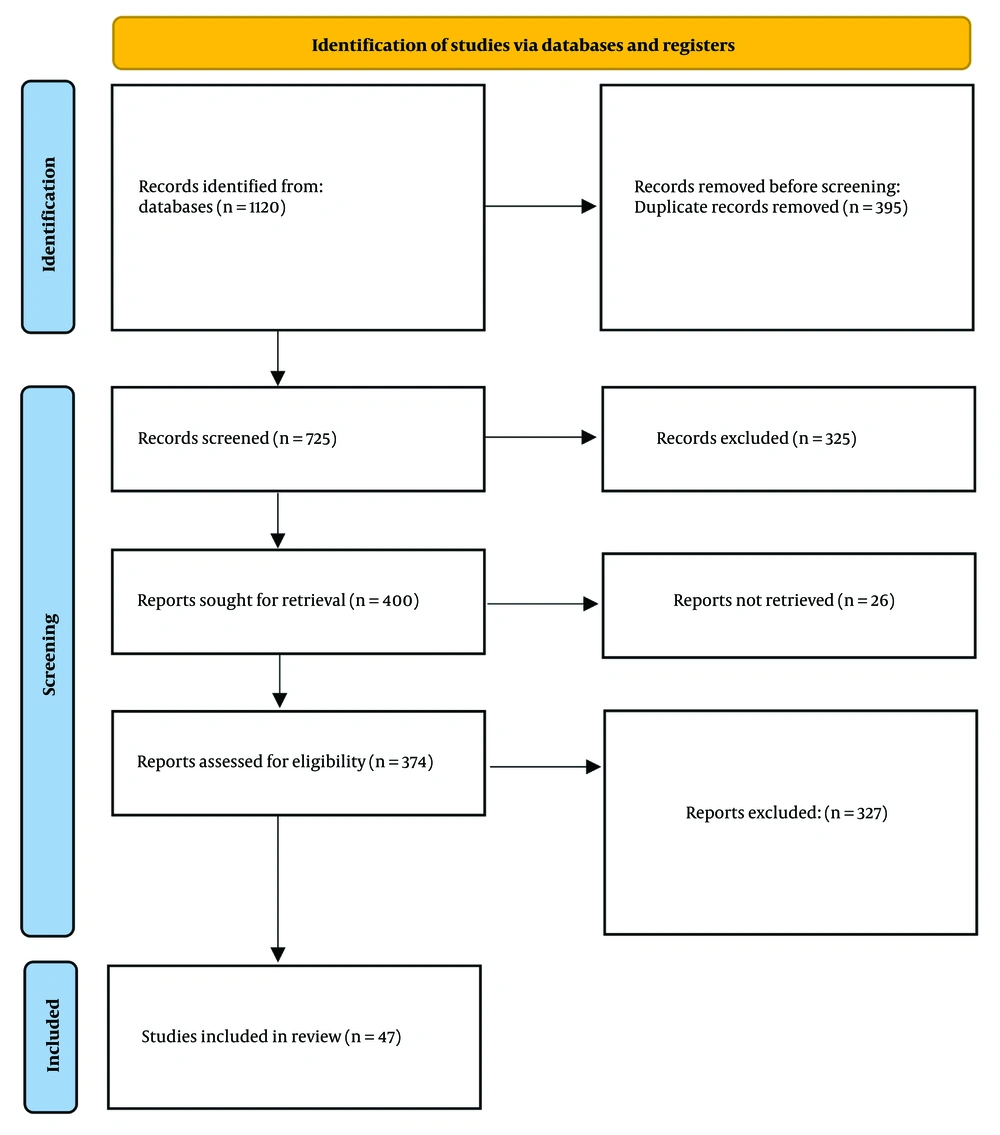

The initial search yielded 1,120 articles, of which 395 duplicate studies were removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 725 studies were reviewed, and 325 studies were excluded due to non-relevance. The full text of the remaining 400 studies was reviewed, resulting in 47 eligible studies for analysis. Figure 1 shows the screening and selection flowchart of articles.

3.3. Data Extraction

Two researchers independently extracted data from the articles to reduce reporting bias and errors in data collection. Extracted data were entered into a pre-prepared list, including the first author’s name, publication year, sample size, study location, questionnaire type, overall domestic violence prevalence, and prevalence of different dimensions of physical, psychological, and sexual violence.

3.4. Checking the Methodological Quality of Articles

Two authors independently evaluated the studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) to assess observational study quality. The NOS checklist covers three aspects: Participant selection, comparability, and outcome evaluation. Checklist questions are answered with an asterisk (*), grading the articles on a 0 - 9 scale. Scores of 0 - 3 indicate low quality, 4 - 6 indicate average quality, and 7 - 9 indicate high quality (21).

3.5. Data Analysis

Each study considered the prevalence of domestic violence as a probability in a binomial distribution, calculating its variance accordingly. The study used the I² Index and Cochrane’s Q-statistic to assess data heterogeneity, categorized as follows: Less than 50% (low heterogeneity), 50 - 75% (moderate heterogeneity), and more than 75% (high heterogeneity). If the I² Index was higher than 50% or the P-value for Cochrane’s Q was less than 0.1, a random effects model was applied; otherwise, a fixed effects model was used. The random effects model was used for all analyses. Meta-regression analysis examined the relationship between total sexual violence prevalence, its dimensions, study year, and average age. Subgroup analysis assessed violence prevalence and dimensions by country, target population, and questionnaire type. Publication bias was evaluated with Egger’s asymmetry regression test and a related graph. All analyses were performed using STATA software version 17, with a significance level of 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Information of the Analyzed Articles

The study analyzed articles published in Farsi and English from 2003 to 2021. Sample sizes ranged from 69 to 2,704 participants, with the average age of women in these studies spanning from 25.7 to 39.5 years. Most studies (8) were conducted in Tehran, the capital of Iran. The overall prevalence of violence was reported in 31 studies, while the prevalence of sexual, physical, and psychological violence was documented in 44 studies. General violence ranged between 18.6% and 98.5%, physical violence ranged from 5% to 91%, mental violence from 7.2% to 99.5%, and sexual violence from 1.5% to 55.1%. Of the total, 13 studies focused on pregnant women, while 34 studies focused on non-pregnant women. Further details are provided in Table 1.

| Author | Year of Publication | City | Sample Size | Mean Age by Year (Range) | Population | Questionnaire | Prevalence (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Violence | Psychological | Physical | Sexual | |||||||

| Esfandabad andEmamipour (22) | 2003 | Tehran | 400 | 18 - 40 | Married women | MSAQ | 0.817 | - | - | - |

| Shams Esfandabadi (23) | 2004 | Tehran | 800 | 18 - 45 | Married women | MSAQ | - | 0.879 | 0.479 | - |

| Shams Esfandabadi (23) | 2004 | Tehran | 200 | 18 - 45 | Plaintiff women who go to the family court due to problems with their husbands | MSAQ | - | 0.995 | 0.91 | - |

| Saberian et al. (24) | 2004 | Semnan | 600 | - | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | - | 0.605 | 0.175 | - |

| Ghahari et al. (25) | 2005 | Tonekabon | 327 | 22.13 | Married students | Spousal Abuse Scale | 0.936 | 0.91 | 0.55 | 0.42 |

| Faramarzi et al. (26) | 2005 | Babol | 2400 | 28.2 | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | - | 0.815 | 0.15 | 0.424 |

| Hemati (21) | 2005 | Zanjan | 300 | 32 | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.26 | - | - | - |

| Malekshahi et al. (27) | 2006 | Koramabad | 1054 | - | Married women | ISA | - | 0.941 | 0.754 | - |

| Jahanfar and Malekzadegan (28) | 2007 | Tehran | 1800 | 25.8 | Pregnant women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.606 | 0.605 | 0.146 | 0.235 |

| Khosravi et al. (29) | 2008 | Sanandaj | 840 | 20-29 | Pregnant women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.605 | 0.57 | 0.085 | 0.188 |

| Balali Meybodi and Hassani (30) | 2009 | Kerman | 400 | 39.5 | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.46 | 0.786 | 0.556 | 0.286 |

| Razaghi et al. (31) | 2010 | Sabzevar | 396 | 29.29 | Married women | ISA | - | 0.292 | 0.108 | 0.28 |

| Hasan et al. (32) | 2010 | Tehran | 370 | 26.27 | Pregnant women | AAS | 0.597 | - | - | - |

| Tabrizi et al. (31) | 2010 | Mashhad | 100 | - | Infertile women | Family violence and sexual satisfaction | - | 0.295 | 0.147 | 0.039 |

| Tabrizi et al. (31) | 2010 | Mashhad | 98 | - | Fertile women | Family violence and sexual satisfaction | - | 0.223 | 0.127 | 0.039 |

| Hasan et al. (32) | 2010 | Miandoab | 650 | - | Pregnant women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.78 | 0.072 | 0.122 | 0.138 |

| Hasan et al. (32) | 2010 | Mahabad | 650 | - | Pregnant women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.674 | 0.083 | 0.223 | 0.086 |

| Hasan et al. (32) | 2010 | Bonab | 650 | - | Pregnant women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.945 | 0.086 | 0.349 | 0.015 |

| Hesami et al. (33) | 2010 | Marivan | 243 | 25.7 | Pregnant women | Violence screening questionnaire | 0.687 | 0.543 | 0.169 | 0.551 |

| Vakili et al. (34) | 2010 | Kazeroon | 702 | 32.4 | Married women | AAQ | - | 0.826 | 0.437 | 0.309 |

| Ardabily et al. (35) | 2011 | Tehran | 400 | 30.09 | Women with primary infertility | CTS2 | 0.618 | 0.338 | 0.14 | 0.08 |

| Nouri et al. (36) | 2012 | Marivan | 770 | 36.5 | Married women | (IPAQ) | - | 0.797 | 0.6 | 0.329 |

| Abbaszadeh et al. (37) | 2012 | Tabriz | 384 | Married women | Spouse Abuse Questionnaire | - | 0.58 | 0.29 | 0.11 | |

| Moasheri et al. (38) | 2012 | Birjand | 414 | 30.01 | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.423 | 0.206 | 0.057 | 0.08 |

| Ranji and Sadrkhanlo (39) | 2012 | Urmia | 824 | - | Pregnant women | Haj Yahya standard questionnaire | 0.363 | 0.448 | 0.225 | 0.417 |

| Jamshidimanesh et al. (40) | 2013 | Tehran | 600 | 26.35 | Pregnant women | AAS | 0.563 | 0.513 | 0.05 | - |

| Torkashvand et al. (41) | 2013 | Rafsanjan | 540 | 31.28 | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.509 | 0.213 | 0.231 | 0.189 |

| Nouhjah and Latifi (42) | 2014 | Dezful | 600 | 28.8 | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.577 | 0.548 | 0.257 | 0.085 |

| Nouhjah and Latifi (42) | 2014 | Andimeshk | 400 | 28.8 | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.51 | 0.465 | 0.14 | 0.098 |

| Nouhjah and Latifi (42) | 2014 | Ahvaz | 600 | 28.8 | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.417 | 0.302 | 0.24 | 0.177 |

| Nouhjah and Latifi (42) | 2014 | Abadan | 220 | 28.8 | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.277 | 0.227 | 0.082 | 0.027 |

| Keyvanara et al.(43) | 2014 | Isfahan | 390 | 28.6 | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | - | 0.528 | 0.249 | - |

| Farrokh-Eslamlou et al. (44) | 2014 | Urmia | 313 | 27.9 | Pregnant women | AAS | 0.559 | 0.435 | 0.102 | 0.172 |

| Abdollahi et al.(45) | 2015 | Mazandaran | 1500 | 26.8 | Pregnant women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.35 | 0.699 | 0.141 | 0.108 |

| Abbaspoor and Momtazpour (46) | 2016 | Isfahan | 600 | 29.16 | Married women | CTS2 | 0.617 | 0.597 | 0.332 | 0.393 |

| Kargar Jahromi et al.(47) | 2016 | Jahrom | 988 | 29.18 | Married women | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.494 | 0.444 | 0.164 | 0.186 |

| Saffari et al. (48) | 2017 | Several cities | 1600 | 30.8 | Iranian women | DVQ | - | 0.64 | 0.28 | 0.18 |

| Esmaeil-Motlagh et al. (49) | 2017 | Several cities | 2704 | - | Pregnant women | Researcher-made questionnaire | - | 0.28 | 0.081 | - |

| Fakharzadeh et al. (50) | 2018 | Abadan | 623 | 31.72 | Married women | demographic questionnaire and a women abuse scale checklist | 0.723 | 0.717 | 0.178 | 0.071 |

| Vaseai et al. (51) | 2019 | Tabriz | 547 | 31.59 | Married women | CTS2 | 0.985 | 0.755 | 0.339 | 0.418 |

| Afkhamzadeh et al. (52) | 2019 | Sanandaj | 360 | Women | Self-report | 0.71 | 0.622 | 0.499 | 0.487 | |

| Sheikhbardsiri et al. (53) | 2020 | Kerman | 400 | 30.23 | Female healthcare workers | Researcher-made questionnaire | 0.975 | 0.58 | 0.292 | 0.1 |

| Keshavarz Mohammadian et al. (54) | 2021 | Gilan | 1541 | 29.2 | Women have given birth | Spouse abuse during pregnancy | 0.713 | 0.695 | 0.322 | 0.151 |

| Sahababadi et al. (55) | 2021 | Delfan | 69 | 15-48 | Married women | Haj Yahya standard questionnaire | - | 0.255 | 0.245 | 0.26 |

| Owaisi and Laloha (56) | 2021 | Qazvin | 450 | - | Pregnant women | AAS and CTS2 | - | 17.7 | 0.06 | 0.018 |

| Hosseini et al. (57) | 2021 | Mashhad | 394 | 18-65 | Married women | Hosseini questionnaire | 0.186 | 0.211 | 0.138 | 0.201 |

| Yari et al. (58) | 2021 | - | 203 | 38.59 | Iranian women during the COVID-19 pandemic | DVQ | 0.349 | 0.261 | 0.266 | 0.212 |

Abbreviations: CTS, Conflict Tactics Scales; ISA, Index Spouse Abuse; AAQ, Abuse Assessment Questionnaire; IPAQ, Intimate Partner Abuse Questionnaire; AAS, Abuse Assessment Screen; DVQ, Domestic Violence Questionnaire; MSAQ, Moffitt's Spousal Abuse Questionnaire.

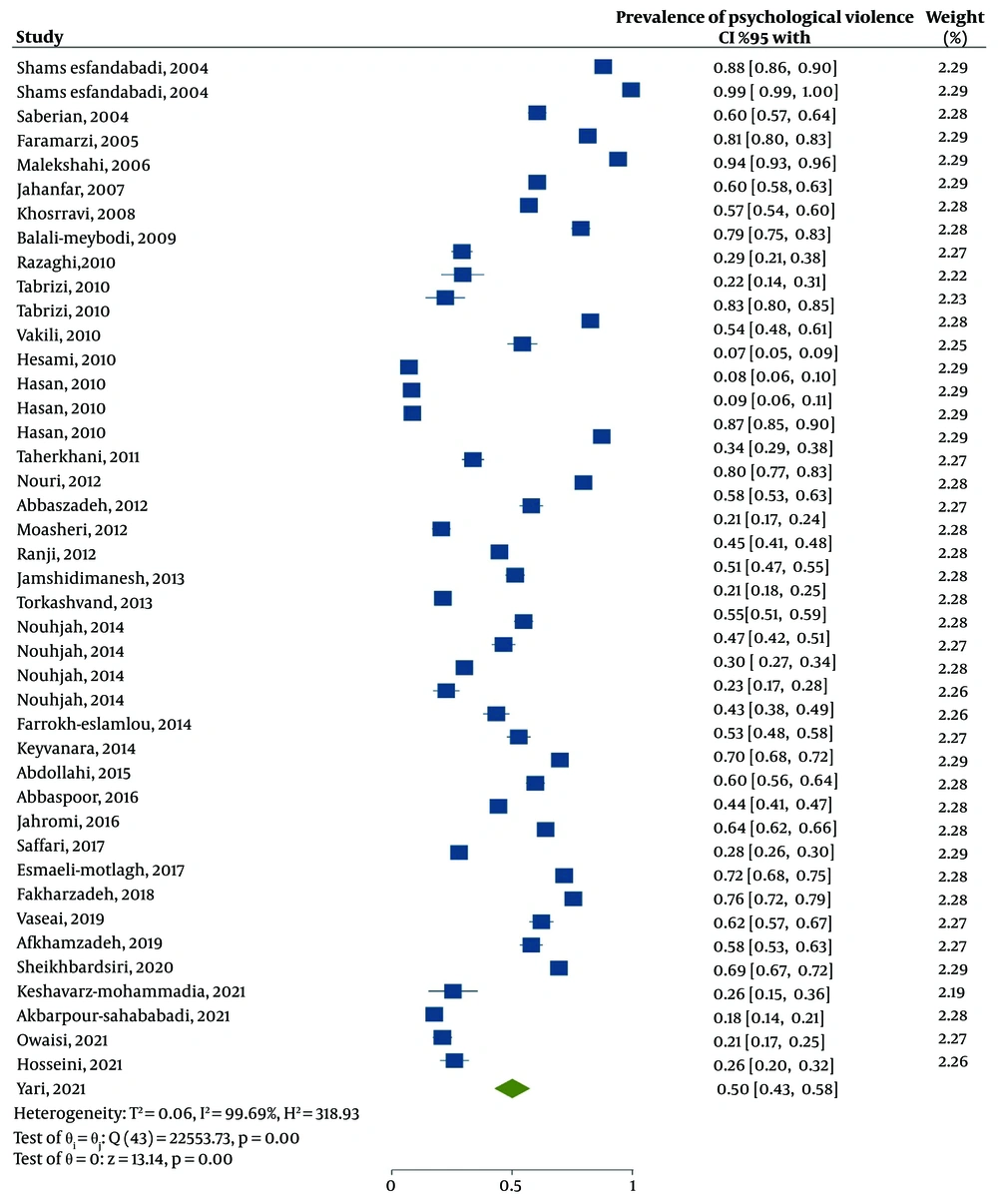

The meta-analysis estimated the pooled prevalence of violence against Iranian women to be 59% (95% CI: 52 - 66). Findings indicated that the highest prevalence of violence was in region 3 (66%; 95% CI: 53 - 79) and region 1 (63%; 95% CI: 50 - 76). For pregnant women, the prevalence was 61% (95% CI: 51 - 71), while in non-pregnant women, it was 58% (95% CI: 36 - 76). Studies using standard tools reported a prevalence of 60% (95% CI: 48 - 71), while those using researcher-made tools reported 58% (95% CI: 48 - 68). The prevalence of specific types of violence was as follows: Physical violence at 25% (95% CI: 0 - 31), mental violence at 50% (95% CI: 43 - 58), and sexual violence at 20% (95% CI: 16 - 25) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

| Violence | Subgroup | Number of Studies | Pooled Prevalence (95% CI) | I2 | Q | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total violence | Region | 1 | 10 | 63 (50 - 76) | 99.20 | 1128.50 | 0.001 |

| 2 | 4 | 55 (43 - 68) | 95.72 | 23.39 | 0.001 | ||

| 3 | 12 | 66 (53 - 79) | 99.61 | 2809.83 | 0.001 | ||

| 4 | 7 | 50 (36 - 65) | 98.29 | 222.27 | 0.001 | ||

| 5 | 8 | 51 (36 - 76) | 99.62 | 2081.84 | 0.001 | ||

| Target | Pregnant | 12 | 61 (51 - 71) | 91.13 | 2094.21 | 0.001 | |

| Non-pregnant | 32 | 58 (47 - 68) | 99.58 | 5572.04 | 0.001 | ||

| Scale | Standard | 23 | 60 (48 - 71) | 99.41 | 3614.55 | 0.001 | |

| Reasearch meade | 21 | 58 (48 - 68) | 99.49 | 4424.61 | 0.001 | ||

| Psychological violence | Region | 1 | 10 | 65 (49 - 81) | 99.81 | 3751.18 | 0.001 |

| 2 | 4 | 60 (44 - 76) | 98.80 | 345.03 | 0.001 | ||

| 3 | 12 | 47 (33 - 62) | 99.66 | 4665.88 | 0.001 | ||

| 4 | 7 | 50 (30 - 69) | 99.52 | 1921.44 | 0.001 | ||

| 5 | 8 | 35 (20 - 50) | 99.68 | 20643.65 | 0.001 | ||

| Target | Pregnant | 12 | 38 (25 - 51) | 99.65 | 3672.89 | 0.01 | |

| Non-pregnant | 32 | 55 (46 - 64) | 99.65 | 9008.50 | 0.01 | ||

| Scale | Standard | 23 | 54 (44 - 65) | 99.66 | 6878.91 | 0.01 | |

| Research made | 21 | 46 (35 - 56) | 99.68 | 9016.73 | 0.01 | ||

| Pysical violence | Region | 1 | 10 | 25 (9 - 41) | 99.82 | 1979.42 | 0.001 |

| 2 | 4 | 30 (18 - 42) | 97.81 | 170.07 | 0.001 | ||

| 3 | 12 | 28 (19 - 37) | 98.98 | 1039.65 | 0.001 | ||

| 4 | 7 | 27 (11 - 43) | 99.37 | 1464.72 | 0.001 | ||

| 5 | 8 | 21 (10 - 32) | 98.53 | 398.66 | 0.001 | ||

| Target | Pregnant | 12 | 15 (10 - 25) | 98.45 | 413.84 | 0.01 | |

| Non-pregnant | 32 | 30 (18 - 42) | 99.30 | 4347.42 | 0.01 | ||

| Scale | Standard | 23 | 29 (20 - 38) | 99.45 | 4317.42 | 0.01 | |

| Research made | 21 | 21 (16 - 27) | 99.10 | 1071.58 | 0.01 | ||

| Sexual violence | Region | 1 | 6 | 21 (7 - 34) | 99.67 | 1505.60 | 0.001 |

| 2 | 3 | 30 (18 - 41) | 97.54 | 88.11 | 0.001 | ||

| 3 | 12 | 25 (15 - 35) | 99.48 | 1563.07 | 0.001 | ||

| 4 | 6 | 11 (5 - 17) | 96.31 | 76.23 | 0.001 | ||

| 5 | 8 | 15 (8 - 22) | 96.78 | 178.01 | 0.001 | ||

| Target | Pregnant | 10 | 19 (9 - 29) | 99.67 | 1239.95 | 0.01 | |

| Non-pregnant | 27 | 21 (16 - 26) | 98.79 | 1974.60 | 0.01 | ||

| Scale | Standard | 19 | 22 (15 - 29) | 99.06 | 1559.48 | 0.01 | |

| Research made | 18 | 18 (12 - 24) | 99.28 | 2212.53 | 0.01 | ||

a Region 1: The provinces of Tehran, Alborz, Qazvin, Mazandaran, Semnan, Golestan, and Qom; Region 2: The provinces of Isfahan, Fars, Boushehr, Chaharmahal va Bakhtiari, Hormozgan, and Kohkilouyeh va Boyerahamad; Region 3: The provinces of Eastern Azarbaijan, Western Azarbaijan, Ardebil, Zanjan, Gilan, and Kurdistan; Region 4: The provinces of Kermanshah, Ilam, Hamedan, Markazi, Lorestan and Khouzestan; Region 5: The provinces of Khorasan Razavi, Southern Khorasan, Northern Khorasan, Kerman, Yazd, and Sistan va Balouchestan.

4.2. Meta-regression Results

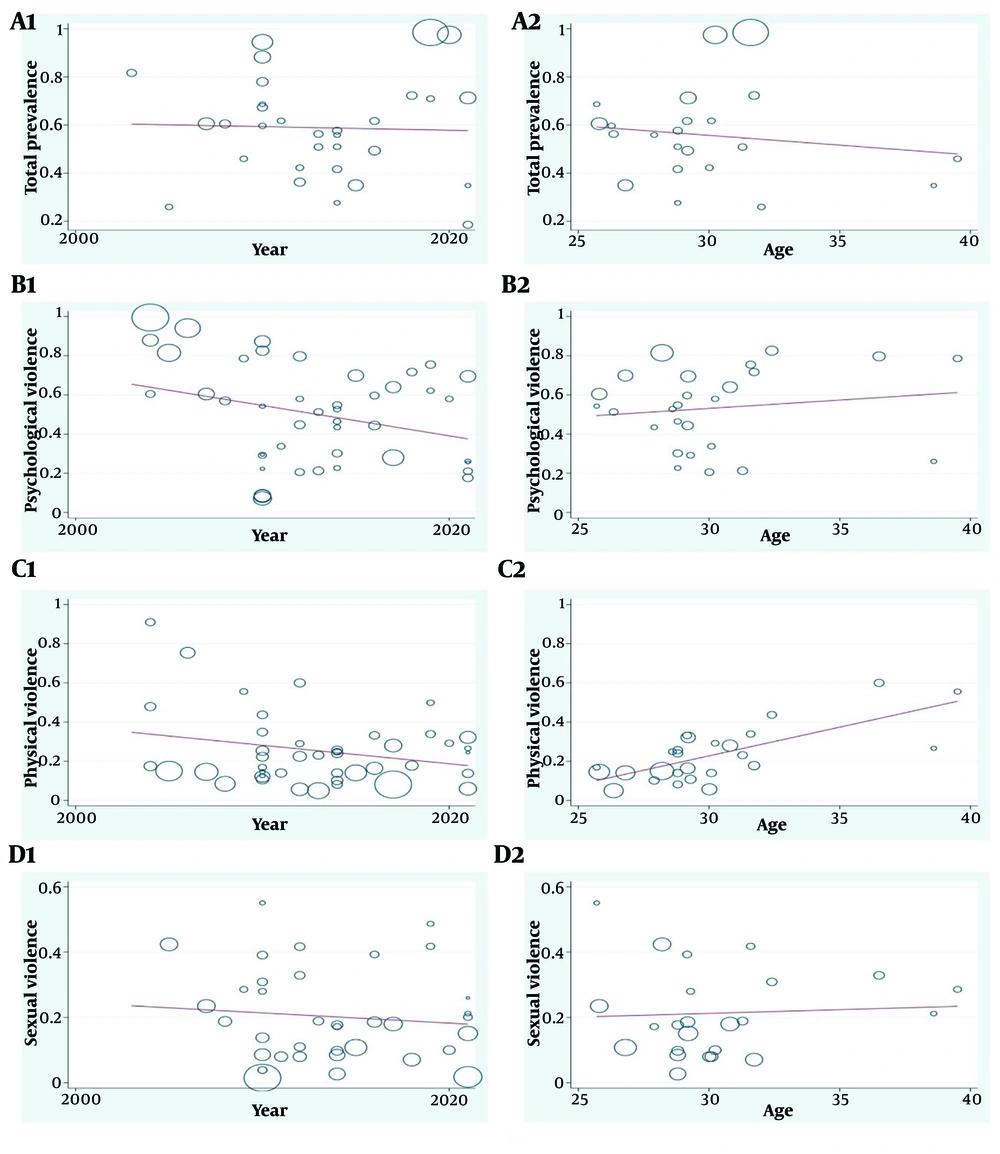

The meta-regression analysis showed no association between the pooled prevalence of violence against women and the average age of women (P = 0.503) or the publication year (P = 0.857). However, the prevalence of psychological violence was significantly related to the year of publication (P = 0.046), with a notable decrease in prevalence from 2003 to 2021. Physical violence prevalence was also significantly associated with the publication year (P = 0.099), showing a similar decrease over this period. In contrast, physical violence prevalence increased significantly with the average age of women (P = 0.001). No significant relationship was found between sexual violence prevalence and either publication year (P = 0.560) or average age of women (P = 0.860) (Figure 3).

The publication bias assessment revealed significant bias for studies examining general violence as well as physical, psychological, and sexual violence (all P = 0.001).

5. Discussion

The study reports that 59% of Iranian women have experienced domestic violence. In Zimbabwe, the prevalence of domestic violence decreased from 45.2% in 2005 to 40.9% in 2010, before rising to 43.1% in 2015. This study identified several risk factors for domestic violence, including younger age, low economic status, cohabitation, and rural residence, though women’s academic achievement was not significantly related to intimate partner violence. The study also indicated that women of reproductive age are at high risk of physical and emotional violence (9). In Mexico, the rate of interpersonal violence ranged from 1% to 83%, with sexual partner violence and domestic violence being the most common types. Victims of intimate partner violence often experience significant persistent mental and physical health problems, including an increased risk of chronic diseases (8). In a study by Rabenhorst et al. on domestic violence among married U.S. Air Force personnel in Iraq, more than 2% reported at least one proven case of physical or emotional abuse, with men committing wife abuse nearly twice as often as women (59). This study found that the prevalence of violence against pregnant women (61%) was higher than among non-pregnant women (58%). Antoniou et al. reported a 6% prevalence of domestic violence during pregnancy, with 3.4% experiencing abuse since the start of pregnancy, primarily by their spouse or partner. Higher risk factors included nationality, socio-economic background, and education level. Foreign women, women with foreign partners, the unemployed, housewives, and university students faced greater harassment risks. Significant age differences (≥ 10 years) between partners, history of abortion, and unwanted pregnancy also increased the risk of violence in pregnancy (12).

Orpin et al. indicated that the prevalence of domestic violence among pregnant women in Nigeria ranged from 2.3% to 44.6%, with lifetime prevalence rates from 33.1% to 63.2%. The study highlighted prenatal care as a critical period for encouraging women to seek help, with psychological violence as the most common type reported (50%), followed by physical (25%) and sexual violence (20%). Additionally, this study revealed that mental and physical violence prevalence decreased significantly from 2003 to 2021. However, physical violence prevalence increased with women’s age (60). Stake et al. found that 29% of women had experienced physical or sexual domestic violence by their husbands. The study also noted that domestic violence rates were higher among women with lower education levels, Muslim women, women under 30, those with a history of family violence, and members of NGOs or microfinance institutions (61).

Results by Kuwan et al. showed a higher combined prevalence of physical violence among men than women, particularly among veterans and soldiers compared to civilians (62). Das and Basu Roy found that women with economic poverty, rural residency, low education levels or illiteracy, larger family sizes, and ages 25 to 35 faced greater risks of violence from their husbands. Contextual factors, including husband’s unemployment and economic poverty, were directly associated with violence levels, while literacy reduced the likelihood of violence against women (63).

Tun and Ostergrenreported physical violence prevalence at 16.8%, sexual violence at 3.8%, emotional violence at 15.9%, and husband’s controlling behavior at 30.2%. Women exposed to controlling behavior from husbands were more likely to experience physical, sexual, and emotional violence. The study also identified poor economic status, justifications for wife-beating, parental violence exposure, and husbands’ alcohol abuse as associated factors (64).

Robinson et al. found that social agencies, health services, and criminal justice systems play crucial roles in supporting individuals exposed to violence (65). Hosseini et al. highlighted domestic violence as a serious social issue in the United States, with South Asian culture limiting victims from reporting, making accurate prevalence rates difficult to determine. Physical violence (48%) was the most common type of victimization, followed by emotional (38%), economic (35%), verbal (27%), immigration-related abuse (26%), spousal abuse (19%), and sexual abuse (11%). Women experienced higher rates of all types of violence compared to men. Education, family structure, and occupation significantly correlated with domestic violence victimization (57).

In Europe, Zapata’s study indicated that 26.1% of women reported at least one act of physical, psychological, or sexual violence. Individual factors such as education, childhood victimization, equal say in income, partner's alcohol use, and partner aggression were associated with higher violence rates. Traditional gender role beliefs correlated with increased sexual victimization rates (66). Orpin et al. identified physical, sexual, psychological, and verbal abuses as the most common types of violence against women. Domestic violence is recognized as a global public health concern that can lead to chronic illnesses. Clinicians, educators, and policymakers are urged to focus on macro-level and individual predictors to help reduce violence (60).

5.1. Conclusions

The studies collectively demonstrate that violence can result in chronic and damaging health conditions. Domestic violence rates are lower in European and American regions but higher in African, Asian, and South American countries. Factors such as education, awareness level, and financial independence are linked to violence rates. Policymakers are encouraged to improve education, awareness, and financial independence to address domestic violence.

5.2. Limitations of the Study

The limitations include the focus on Iran as the study population, a limited number of studies reviewed, an uneven distribution of studies across Iranian cities, the variety of questionnaires used in reviewed studies, and the inability to perform a subgroup analysis for age due to the narrow age range in the studies examined.