1. Background

Cystic fibrosis (CF) stands as the most common fatal autosomal recessive disorder (1). Cystic fibrosis is the result of a mutation in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene located on chromosome 7 (2). In the digestive system, CF often leads to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and changes in intestinal motility (3, 4). These effects on intestinal motility might manifest as meconium ileus, distal intestinal obstruction, or chronic constipation (5). The incidence of CF varies according to ethnic origin, ranging from 1 in 2 000 to 1 in 3 500 newborns in different countries (6). Respiratory problems are the leading cause of mortality and morbidity among CF patients (7, 8). Children with pancreatic insufficiency (PI) typically require fat-soluble vitamins, including A, D, E, and K.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the clinical presentation and laboratory findings in children with CF.

3. Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted on children diagnosed with CF over a 2-year period starting in 2018. The medical records of CF patients were reviewed. The diagnosis of CF was confirmed through clinical manifestations, sweat chloride tests, or genetic studies. Children aged ≥ 2 years were included; however, those lacking sweat chloride tests or genetic studies were excluded. This study recorded demographic features, gastrointestinal manifestations, vitamin D levels, and the number of hospital admissions. A pediatric gastroenterologist conducted fecal elastase and stool fat analyses to evaluate PI. Vitamin D levels < 30 ng/mL were considered vitamin D insufficiency, and levels < 20 ng/mL indicated vitamin D deficiency. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 25.0).

4. Results

The study included 59 children, 37 (62.71%) and 22 (37.28%) of whom were male and female, respectively. The mean age was 7.1 ± 4.6 years, ranging from 2 to 18 years (median: 6 years). Table 1 shows weight percentiles, with 67.8% of children having a weight percentile below 5. Table 1 also displays height percentiles, where 50.8% of children had a height below the 5th percentile. Body mass index (BMI) data are presented in Table 1, and no children were observed with a BMI ≥ 95 kg/m2. Among the 59 children, 51 subjects (86.4%) had parents who were relatives, and 24 cases (40.7%) had a sibling with CF. In one case, a genetic study alone was used for diagnosis; however, 53 children were diagnosed solely through sweat tests. Five children underwent both a sweat chloride test and a genetic study for diagnosis. Age at diagnosis was < 6, 6 - 12, and > 12 months for 27 (45.8%), 7 (11.9%), and 25 (42.3%) of the cases, respectively.

Among all patients, 45.8% were diagnosed within the first 6 months of life. The most common initial clinical presentations were failure to thrive (FTT), observed in 29 (49%) cases, and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections, noticed in 27 (45%) cases (Table 2).

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Weight percentile | |

| Valid | |

| < 5 | 40 (67.8) |

| 5 - 10 | 6 (10.2) |

| 10 - 25 | 6 (10.2) |

| 25 - 50 | 5 (8.5) |

| 50 - 75 | 2 (3.3) |

| Total | 59 (100) |

| Height percentile | |

| Valid | |

| < 5 | 30 (50.8) |

| 5 - 10 | 8 (13.6) |

| 10 - 25 | 5 (8.5) |

| 25 - 50 | 3 (5.1) |

| 50 - 75 | 7 (11.9) |

| 75 - 90 | 6 (10.1) |

| Total | 59 (100) |

| BMI percentile | |

| Valid | |

| < 5 | 34 (57.6) |

| 5 - 10 | 5 (8.5) |

| 10 - 25 | 6 (10.1) |

| 25 - 50 | 5 (8.5) |

| 50 - 75 | 5 (8.5) |

| 75 - 90 | 2 (3.4) |

| 90 - 95 | 2 (3.4) |

| Total | 59 (100) |

Frequency of Weight, Height, and Body Mass Index Percentiles Among Participants

| First Presentation at Diagnosis | No (%) |

|---|---|

| FTT | 29 (49.2) |

| Recurrent RTI | 27 (45.8) |

| Steatorrhea | 11 (18.6) |

| GIO | 5 (8.5) |

| Anemia | 1 (1.7) |

| Chronic cough | 6 (10.2) |

| Salty skin | 6 (10.2) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (3.4) |

| Genetic history | 2 (3.45) |

First Presentation at Diagnosis

The number of hospital admissions in the 2 years prior to the study ranged from 1 to 20, with a median of 3 during that period. Out of the 59 cases, 44 subjects (74.6%) received a recommendation for pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) from a physician. Thirty-two (54%) of the cases adhered to vitamin D supplementation as prescribed; nevertheless, 27 cases (45%) either did not use it or discontinued it. Among the patients, 34 subjects (58%) reported gastrointestinal complaints, with 19 cases (32%) experiencing abdominal pain, 13 cases (22%) having a loss of appetite, and facing defecation problems, such as constipation or diarrhea was seen in 22% of the patients.

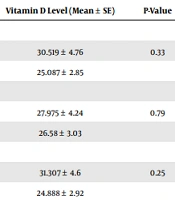

Vitamin D consumption ranged from 0 to 100 000 units per month, with a mean of 100 542 ± 155 691 units among patients. There was no significant correlation between the number of hospital admissions and monthly vitamin D consumption (Pearson coefficient = 0.155, P = 0.240) (Table 3). Among the 47 patients with available vitamin D assessment results, the mean ± standard error (SE) was 26.93 ± 17.02, ranging from 3 to 67 ng/mL. In this group, 60% of children had insufficient vitamin D levels (25-OHD < 30 ng/mL). A significant correlation was observed between the level of vitamin D and the number of hospital admissions (Pearson coefficient = 0.298, P = 0.042).

| Vitamin D Level (Mean ± SE) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | ||

| Yes (n = 16) | 30.519 ± 4.76 | 0.33 |

| No (n = 31) | 25.087 ± 2.85 | |

| Defecation changes | ||

| Yes (n = 12) | 27.975 ± 4.24 | 0.79 |

| No (n = 35) | 26.58 ± 3.03 | |

| Lack of appetite | ||

| Yes | 31.307 ± 4.6 | 0.25 |

| No | 24.888 ± 2.92 |

Correlation Between Level of Vitamin D and Gastrointestinal Complications

The mean white blood cell count (WBC) was 13 332.24 ± 6 340.849 /mL, ranging from 5 200 to 46 000. Qualitative C-reactive protein (CRP) results were available for 42 cases, with 25 cases (47.2%) showing negative results, 10 cases (16.9%) displaying a +1 CRP, and 14 cases (23.7%) having 2+ CRP; nevertheless, 4 cases (6.8%) had 3+ CRP.

Children receiving PERT had a mean of 3.59 ± 0.429 hospital admissions; nonetheless, children without PERT had 4.20 ± 1.284 hospital admissions. There was no correlation between PERT and the number of hospital admissions (P = 0.65). Table 3 shows that there was no correlation between the level of vitamin D and abdominal pain, defecation changes, or loss of appetite.

The mean BMI among children receiving PERT was 14.04 ± 1.98 kg/m2; nevertheless, for those without PERT, it was 14.57 ± 3.09 kg/m2. No significant difference was observed in this regard (P = 0.9). The mean height among children receiving PERT was 1.10 ± 0.22 m; however, those without PERT had a mean height of 1.10 ± 0.27 m (P > 0.05).

5. Discussion

In this study, 62% of the cases were male, which is consistent with the findings of Aziz et al. (9), where 58.13% of CF children were male, similar to the current study. In the current study, 40.7% of patients had a sibling with CF; however, in Ziyaee et al.’s study, only 13.3% of CF patients had a sibling with CF (10).

Among all patients, 67% had a weight percentile < 5, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) standards. However, the prevalence of malnutrition decreased, according to the report of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Among the children, 50.8% had a height percentile below 5, according to the CDC height curve. Increasing caloric intake can lead to higher weight-for-age in children with CF (11). Nutritional management should be initiated as early as possible after diagnosis (12). Weight and height measurements should be performed at each patient visit (13). Growth failure in children with CF might be due to factors such as airway inflammation, chronic inflammation, undernutrition, or malnutrition (14).

In this study, 57% of children were diagnosed before the age of 1 year. According to a report from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the median age of diagnosis was 3 months. In another study, 64% of patients were diagnosed before the age of 3 years (15). In a study from Egypt, the average age at diagnosis was 3.9 years (16). It seems that the diagnosis of CF in the present study was made earlier than in other studies, possibly due to more experience in the investigated center.

In the present study, FTT was the most common clinical presentation at the time of diagnosis, observed in 49.2% of the cases. Farahmand et al. also observed FTT to be the most common clinical presentation in their study (17). Routine screening of newborns for CF in resource-rich communities has decreased the symptomatic presentation of CF (18).

In Aziz et al.’s study, chronic cough was the most common initial symptom of CF (9). Cough was also observed in 77% of Bahreini children in Isa et al.’s study (15). Gastrointestinal obstruction (GIO) was observed in 8.5% of the cases. Intestinal obstruction among CF patients might be due to distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS) or meconium ileus obstruction (19).

Among the studied cases, 22% had a loss of appetite. Papantoni et al. observed that children with feeding aids, such as gastric tubes or appetite stimulation medications, demonstrated greater food avoidance (20). Tabori et al. reported a lack of appetite in 130 out of 131 children with CF, which is significantly higher than in the present study (21).

Pancreatic insufficiency was present in 74.6% of the current study’s cases. Pancreatic insufficiency can be treated with enzyme replacement therapy (22). In Calvo-Lerma et al.’s study that included 6 European CF centers, PI was reported in 80 - 100% of the children (23). The rate of PI in the current study was slightly lower than in the study by Calvo-Lerma et al. (23). However, the sample size and duration of the study might affect the frequency of PI.

Among the current study’s patients, 54% reported using vitamin D. Additionally, 60% had 25OH-D levels < 30 ng/mL. Vitamin D insufficiency is common in CF patients (24). Lai et al. reported vitamin D insufficiency in 22% of children with CF (25). Children with CF have significantly lower serum levels of 25OH-D than non-CF individuals (26). In another study, 89% of children had 25OH-D levels lower than 30 ng/mL (27). In a study from the USA, 7% of children had vitamin D deficiency, and 36% had insufficiency (28). The rate of vitamin D insufficiency in Iran was higher than in the USA. In Rovner et al.’s study, vitamin D levels remained low despite routine oral supplementation of vitamin D among children and adolescents with CF (29). In another study from Brazil, 64.6% of the children showed vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency (30).

The current CF guidelines recommend ≥ 800 IU/day of vitamin D supplementation for children aged > 1 year (31). Despite the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s recommendation, deficiency in vitamin D remains common in children with CF (32). Norton et al. observed vitamin D deficiency in 23 - 26% of children with CF within 2 years of the study (33). Genetic factors might play a role in variable responses to vitamin D supplements in CF (34).

There is a significant correlation between vitamin D levels and the number of hospital admissions in the present study. Another study showed that higher vitamin D levels among children and adolescents with CF were associated with a lower rate of pulmonary exacerbations (35). Queiroz et al. observed an association between vitamin D hypovitaminosis and inflammatory markers in their study (30). In a recent systematic review by Iniesta et al., 25-OHD concentration was positively associated with lung function in children and young adults with CF (36). Dediu et al. observed that vitamin D deficiency was associated with cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD), cystic fibrosis liver disease (CFLD), and prolonged lung clearance index in their study (37).

The rate of hospital admission among children with CF depends on several factors. In the present study setting, some patients had a lower economic status, which limited their access to certain drugs. For example, Creon was sometimes unavailable for children.

As mentioned earlier, despite early diagnosis and management, the rate of poor weight gain and short stature in the current study was high. This finding might be attributed to the high frequency of malnutrition reported in previous studies unrelated to CF (38).

5.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations, including its single-center design and financial constraints. Due to financial limitations, it was impossible to assess other fat-soluble vitamins and conduct pulmonary function tests. Additionally, the retrospective nature of the study might introduce potential biases. Laboratory examinations were performed in referral laboratories for children with CF, and demographic variables, such as ethnicity, were not reliable and, therefore, were not included in the analysis.

5.2. Conclusions

The present study highlights the common occurrence of vitamin D insufficiency and FTT among children with CF. There was a significant correlation between vitamin D levels and the number of hospital admissions over a 2-year period. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of nutritional status and vitamin D levels in children with CF, it is recommended that a multicenter prospective study be conducted.