1. Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) impacts the brain and spinal cord, leading to a broad spectrum of physical and mental symptoms (1-3). Currently, an estimated 2.8 million people globally live with MS. The incidence rate across 75 reporting countries is approximately 2.1 per 100,000 individuals, with the average age of diagnosis being 32 years. Women are twice as likely to develop MS compared to men (4). In Iran, MS prevalence ranges from 5.3 to 89 per 100,000 people (5). Typical clinical symptoms of MS include motor and sensory disturbances, balance issues, cognitive deficits, weakness, pain, bladder and sexual dysfunction, depression, visual problems, fatigue, and various psychosocial and physical symptoms (6).

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is associated with significant emotional and physical impacts. A majority of individuals with MS experience mild to moderate levels of social stigma. Stigma is characterized by feelings of being different from others and can lead to adverse outcomes such as low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, reduced quality of life, and either self-devaluation or social isolation (7-9). Understanding the effects of perceived stigma on various aspects of patients' lives is crucial for developing effective strategies to manage stigma and its consequences (2). Previous research on conditions such as epilepsy (10), infertility in women (11), schizophrenia (8), and HIV (9) indicates that perceived stigma significantly affects self-esteem, suicide risk, and quality of life (12).

Patients employ various strategies to respond to experiences of stigmatization. Coping strategies are crucial at every stage of an illness (3). The term 'coping' refers to the methods used to manage psychological distress (7). Lazarus and Folkman identify 2 primary coping methods for psychological distress: Problem-oriented coping and emotion-oriented coping. Additionally, coping strategies can be categorized as positive (adaptive) or negative (maladaptive). Effective coping strategies for handling psychological distress typically have positive outcomes. Conversely, less flexible and inappropriate coping strategies tend to have negative consequences. The selection of coping strategies is influenced by factors such as the type of stressor, perception of the stressor, available resources, and the effectiveness of the coping mechanism (12-14).

In examining coping strategies among MS patients, a review of the literature revealed inconsistent findings and identified a need for further research. While some studies suggest that MS patients tend to use more problem-focused coping strategies compared to healthy individuals (6, 15, 16), Mikaeili et al. (17) observed that MS patients more frequently employed emotion-focused coping strategies.

2. Objectives

To our knowledge, no study has yet explored the relationship between stigma and coping strategies in MS patients in Iran. Therefore, the objective of this study is to determine the association between external and internal stigma and coping strategies in MS patients.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

This study employed a descriptive-correlational design and involved 100 MS patients attending a neurology clinic at Bu Ali Sina Hospital in Qazvin, Iran.

3.2. Participants

The sample size was determined considering α = 0.05 (95% confidence interval), β = 0.1 (90% power), the correlation coefficient (r = 0.35) from a previous study (18), and an anticipated 10% non-response rate. Consequently, the final sample size was established as 100.

Patients were recruited through convenience sampling. Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of MS by a neurologist, being 18 years or older, having MS for more than one year, being conscious, possessing stable vital signs, being able to read and write in Persian, having oral communication skills, and expressing an interest in participating in the study. Individuals with current or previous neurological diseases other than MS were excluded.

3.3. Measurements

Data collection involved the use of demographic and illness information checklists, the Lazarus Coping Strategies Questionnaire, and the Korean version of the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness 8-item (SSCI-8).

The demographic and clinical characteristics recorded included age, gender, education level, marital status, employment, financial status, history of chronic illness, family history of MS, medication use, duration of MS, and hospitalization history.

Folkman and Lazarus developed the "Ways of Coping Questionnaire" in 1985. This instrument comprises 66 items, each rated using a four-point Likert scale (19). The scale encompasses eight coping strategies, categorized into emotion-focused coping, including confronting (6 questions), distancing (6 questions), self-controlling (7 questions), escape-avoidance (8 questions), and problem-focused coping, comprising social support (6 questions), accepting responsibility (4 questions), planned problem solving (6 questions), and positive reappraisal (7 questions). The questionnaire also includes distraction questions. Responses are scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “does not apply and/or not used” to 3 = “used a great deal.” Higher scores on each subscale indicate more frequent use of the corresponding coping strategy (20). Alipour et al. (21) translated the questionnaire into Persian and validated its content. Ramzi et al. (22) reported high internal consistency for this questionnaire (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to be 0.96.

In the SSCI-8 (Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness 8-item), responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The total score ranges from 8 to 40, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of perceived stigmatization. The SSCI-8 has demonstrated high internal consistency, validity, and a unidimensional structure for the underlying construct of perceived stigma (23) Daryaafzoon et al. (24) translated the scale into Persian using a forward-backward procedure and confirmed the face and construct validity of the scale in Iranian women with breast cancer. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was calculated to be 0.78.

The first author distributed the questionnaires to eligible patients visiting the neurology clinic. The patients completed the questionnaires in the clinic, and any questions they had were addressed. The sampling process spanned six months, from December 2019 to June 2020.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and frequency distribution) were used, along with Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients. A P-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences (IR.QUMS.REC.1398.312). Patients were informed about the confidentiality of their data and provided with the necessary explanations for completing the questionnaire. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to data collection.

4. Results

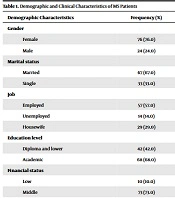

A total of 100 MS patients, with an average age of 35.93 ± 7.20 years, participated in this descriptive cross-sectional study. The majority of the patients were women (n = 76, 76.0%), married (n = 67, 67.0%), employed (n = 57, 57.0%), and held academic degrees (n = 68, 68.0%). Over 70% of the participants fell into the middle-income bracket (n = 73, 73.0%). Approximately 76% of the patients reported no comorbid chronic diseases, and 87.0% did not have a family history of MS (Table 1).

| Demographic Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 76 (76.0) |

| Male | 24 (24.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 67 (67.0) |

| Single | 33 (33.0) |

| Job | |

| Employed | 57 (57.0) |

| Unemployed | 14 (14.0) |

| Housewife | 29 (29.0) |

| Education level | |

| Diploma and lower | 42 (42.0) |

| Academic | 68 (68.0) |

| Financial status | |

| Low | 10 (10.0) |

| Middle | 73 (73.0) |

| Good | 16 (16.0) |

| Excellent | 1 (1.0) |

| History of chronic illnesses | |

| Yes | 24 (24.0) |

| No | 76 (76.0) |

| Family history | |

| Yes | 13 (13.0) |

| No | 87 (87.0) |

| Medication use | |

| Yes | 73 (73.0) |

| No | 27 (27.0) |

| Disease duration | |

| <1 | 19 (19.0) |

| 1 - 5 | 39 (39.0) |

| 5 - 10 | 19 (19.0) |

| >10 | 23 (23.0) |

The average scores for internal and external stigma were 6.47 ± 2.03 and 8.73 ± 3.48, respectively. The study found that the most frequently utilized coping strategies by the participants were accepting responsibility (5.35 ± 2.68), distancing (7.72 ± 3.97), problem-solving (7.45 ± 3.76), and positive reappraisal (8.73 ± 4.38), while the least used were escape-avoidance (8.12 ± 4.21) and confronting (6.39 ± 3.09). Additionally, MS patients tended to use problem-focused coping strategies more than emotion-focused strategies (Table 2).

| Variables and Subscales | Mean ± SD | Mean/No. of Items | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigma | ||||

| Internal | 6.47 ± 2.03 | 2.16 | 3 | 12 |

| External | 8.73 ± 3.48 | 1.75 | 5 | 18 |

| Total | 15.20 ± 4.81 | 1.9 | 8 | 28 |

| Coping Strategies | ||||

| Problem-focused | 36.56 ± 16.50 | 2.82 | 1 | 79 |

| Emotion-focused | 30.75 ± 13.49 | 2.44 | 1 | 66 |

| Confronting | 6.39 ± 3.09 | 1.07 | 0 | 15 |

| Distancing | 7.72 ± 3.97 | 1.29 | 1 | 18 |

| Self-controlling | 8.52 ± 4.34 | 1.22 | 0 | 17 |

| Seeking social support | 6.91 ± 4.06 | 1.16 | 0 | 17 |

| Accepting responsibility | 5.35 ± 2.68 | 1.34 | 1 | 12 |

| Escape-avoidance | 8.12 ± 4.21 | 1.02 | 0 | 20 |

| Problem-solving | 7.45 ± 3.76 | 1.24 | 0 | 18 |

| Positive reappraisal | 8.73 ± 4.38 | 1.24 | 0 | 19 |

| Total | 59.19 ± 25.77 | 0.90 | 2 | 122 |

Spearman's correlation analysis was conducted to explore the associations between demographic and clinical variables and internal or external stigma. The findings revealed inverse correlations between the level of education and the degree of internal stigma (r = -0.273, P = 0.006), as well as between the duration of MS and external stigma (r = -0.296, P = 0.003) (Table 3).

| Variables | Internal Stigma | External Stigma | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P-Value | R | P-Value | |

| Gender | 0.091 | 0.365 | -0.099 | 0.326 |

| Marital status | 0.091 | 0.368 | -0.132 | 0.191 |

| Job | -0.076 | 0.452 | 0.080 | 0.426 |

| Educational level | -0.273 | 0.006 | 0.161 | 0.108 |

| Financial status | -0.130 | 0.199 | 0.010 | 0.924 |

| History of chronic illnesses | -0.053 | 0.601 | 0.073 | 0.471 |

| Family history | -0.096 | 0.343 | -0.019 | 0.853 |

| Medicine use | -0.083 | 0.410 | 0.096 | 0.341 |

| Disease duration | 0.138 | 0.171 | -0.296 | 0.003 |

As indicated in Table 4, internal stigma was significantly correlated with escape-avoidance (r = 0.391, P < 0.000), seeking social support (r = 0.215, P = 0.031), confronting (r = 0.240, P = 0.016), and self-controlling (r = 0.222, P = 0.026). This suggests that an increase in internal stigma is associated with greater use of escape avoidance, social support, confronting, and self-controlling strategies. Furthermore, individuals with higher internal stigma were found to more frequently employ emotion-focused coping strategies. Additionally, the results demonstrated that external stigma was significantly correlated with escape-avoidance (r = 0.322, P = 0.001) and confronting (r = 0.240, P = 0.016), indicating that an increase in external stigma is linked to increased use of escape-avoidance and confronting strategies.

| Coping Strategies | Internal Stigma | External Stigma | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P-Value | r | P-Value | |

| Reappraisal | 0.105 | 0.297 | -0.007 | 0.946 |

| Problem-solving | 0.173 | 0.085 | 0.140 | 0.165 |

| Escape | 0.391a | 0.000 | 0.322a | 0.001 |

| Responsibility | 0.172 | 0.087 | -0.037 | 0.712 |

| Social support | 0.215b | 0.031 | 0.095 | 0.347 |

| Self-controlling | 0.222b | 0.026 | 0.125 | 0.215 |

| Distancing | 0.039 | 0.700 | -0.115 | 0.254 |

| Confronting | 0.240b | 0.016 | 0.281 a | 0.005 |

| Emotion-focused | 0.246b | 0.014 | 0.160 | 0.111 |

| Problem-focused | 0.188 | 0.062 | 0.053 | 0.602 |

| Total | 0.231b | 0.021 | 0.122 | 0.228 |

a P ≤ 0.01.

b P ≤ 0.05.

5. Discussion

This study examined the impact of perceived stigma on the coping strategies of MS patients. The results indicated a predominance of female patients, aligning with findings by Spencer et al. (7), Öz (6), and Zengin et al. (3), who observed a higher vulnerability to MS in women compared to men. Gender is a significant risk factor for MS, with various hormone-related physiological stages such as puberty, pregnancy, puerperium, and menopause markedly influencing the prevalence and outcomes of MS in women (25, 26). Hormonal maturation plays a role in the sex-specific risk for MS; while the prevalence of MS is comparable between genders before puberty, it increases substantially in women post puberty (25).

The findings of this study revealed that MS patients utilize both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies, with a predominant use of problem-focused strategies. This aligns with Lazarus and Folkman's theory, which suggests that individuals typically employ a combination of problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies when facing stressful situations (13). Similar findings were reported by Öz (6), Ahadi et al. (15), and Nada et al. (16), who observed that MS patients tend to use more problem-focused coping styles compared to healthy individuals. These strategies are linked to psychosocial adjustment indicators (27), improved mental health (28), and enhanced overall quality of life (29). Carver et al.'s theory also posits that problem-focused coping strategies facilitate adaptation to stressful circumstances (30). However, Mikaeili et al. (17) discovered that MS patients were more inclined to use emotion-focused coping strategies to address their problems. The variation in results may be attributed to factors such as disease severity, level of dependence, and the social and structural context.

The findings of this study indicate that MS patients with higher levels of external or internal stigma are more likely to employ emotion-focused coping strategies. This underscores the detrimental effect of stigma on the mental health of individuals with MS, leading them to adopt emotion-focused strategies that adversely impact their adjustment and quality of life (31). Corroborating these results, Tran et al. (32) found that HIV patients with greater internalized stigma tended to use more emotion-focused strategies. Similarly, Holubova et al. (33) demonstrated a direct and significant link between the use of emotion-focused coping strategies and increased internalized stigma in schizophrenia patients. Stigma has been conceptualized by several researchers as a potent stressor that can exacerbate clinical symptoms and potentially trigger illness relapse (34-36). Consequently, MS patients utilize coping strategies to manage the stress and depression caused by stigma (31). Identifying approaches that mitigate self-stigma and reduce excessive avoidance behavior may, therefore, be crucial.

This study also revealed that higher educational levels were associated with reduced internal stigma. This finding aligns with Ghanean et al. (37), who reported that epilepsy patients with lower educational attainment experienced more perceived stigma. Individuals with higher education may adhere more effectively to treatment, thereby better controlling their condition and subsequently reducing stigma.

Furthermore, the study observed that a longer duration of MS was associated with decreased external stigma. This is consistent with Spencer et al. (7), who found that individuals with a longer history of MS reported lower levels of stigma. A possible explanation for the reduction in stigma over time is the increased likelihood of accessing effective medical care and experiencing symptom improvement in MS. Additionally, a prolonged duration of living with MS might lead to the development of adaptive coping mechanisms. However, Sohrabi et al. (38) did not find a significant link between the duration of MS and stigma in psychiatric patients, and Mahdilouy and Ziaeirad (39) also found no significant correlation between external stigma and the duration of type 1 diabetes. These discrepancies could be attributed to differences in the nature of the diseases under investigation.

5.1. Limitations and Strengths

This study is the first in Iran to explore the relationship between perceived stigma and coping strategies in MS patients, providing valuable insights into their coping mechanisms and how these relate to perceived stigma. However, there are limitations. Since the research was conducted with Iranian MS patients, generalizing the results to individuals with different conditions or from other cultural backgrounds may be challenging. Additionally, the use of convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the study design and analytical approach constrain the results to associations rather than causal relationships.

5.2. Suggestions for Future Studies

Future research is recommended to investigate the relationship between perceived stigma and coping strategies in patients with various chronic diseases and across different age groups.

5.3. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that coping strategies employed by MS patients are influenced by their level of stigma. Patients experiencing higher stigma tended to use emotion-focused strategies, which often did not effectively reduce their stress. Thus, training programs that teach effective coping strategies are essential to enhance the adoption of beneficial coping mechanisms by these patients.