1. Background

Throughout the world, even in underserved areas, coronary care has increasingly become a vital part of the management of critically ill patients (1). The coronary care unit (CCU) admission puts huge psychological and physical stress on the patient. One of the psychological stressors for CCU patients is being away from family members and inadequate visiting hours (2). Today, the CCU environment includes both the patient and his/her family. Accordingly, caring for the patient’s family is also essential (3). The stressors experienced by family members increase many of their specific needs (4). One of the special needs of families is to visit patients during their hospitalization (3). Recent studies show that with preventive strategies, such as family-focused professional care, it is possible to reduce the incidence of dysfunction in the family (5). Patients admitted to the CCU ward tend to be visited by close family members (6). On the other hand, the families of CCU patients are also intended to visit the patient and have a flexible visiting policy (7).

CCU visiting has always been a challenging topic among healthcare professionals, patients, and visitors (8). Therefore, in order to implement CCU visiting rules, the needs of the staff, patients, and visitors must be taken into account, and a visiting policy must be adopted that ensures the most effective visiting system (9).

“It is time to open the doors of CCUs that have been closed so far,” Burchardi wrote in a medical journal of intensive care. All patients and families and the whole CCU team will benefit from this policy (10). However, visiting hours in CCUs still follow strict and restrictive rules in Iran, and there does not seem to be a will to change these rules (11).

According to the researcher’s experience, disregarding the needs of users, including patients, families, and hospital staff, in making the existing visiting policy sometimes manifests itself in the form of aggression, protests against staff, and complaints to superiors.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to design a visiting policy based on the challenges of the CCU ward using an interactive approach.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This qualitative research was conducted using a qualitative method and participatory action research (PAR) approach in Ganjavian Hospital in 2016 in Dezful City, Iran.

3.2. Participants and Setting

The purposeful sampling method was used for forming focus groups, including cardiologists, CCU nurses, supervisors, CCU service staff, security guards, inpatients, visitors of CCU patients, and relevant managers who make the final decisions on CCU programs and rules. Therefore, 40 participants, including 7 patients, 7 patient companions, 5 relevant managers, 3 physicians, 9 nurses, 3 supervisors, 3 service staff, and 3 security guards, were selected using the purposeful sampling method and entered the research (Table 1).

| Number | Position | Education Level | Gender | Years of Service | Work Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Manager of Medical University | General Practitioner M.D. | Male | 26 | Vice President of Medical University |

| 2 | Hospital internal director | Clinical Psychology Ph.D. | Male | 26 | Hospital management office |

| 3 | Hospital matron | Nursing M.S. | Male | 16 | Nursing office |

| 4 | Responsible for handling complaints | Nursing B.S. | Female | 22 | Quality improvement unit |

| 5 | Head nurse | Nursing B.S. | Male | 25 | CCU |

| 6 | Medical doctor | Interventional Fellowship-Cardiologist M.D. | Male | 4 | CCU |

| 7 | Medical doctor | Cardiologist M.D. | Male | 25 | CCU |

| 8 | Medical doctor | Cardiologist M.D. | Female | 6 | CCU |

| 9 | Nurse | Nursing M.S. | Female | 10 | CCU |

| 10 | Nurse | Nursing B.S. | Female | 22 | CCU |

| 11 | Nurse | Nursing B.S. | Female | 21 | CCU |

| 12 | Nurse | Nursing B.S. | Female | 18 | CCU |

| 13 | Nurse | Nursing B.S. | Female | 15 | CCU |

| 14 | Nurse | Nursing B.S. | Female | 14 | CCU |

| 15 | Nurse | Nursing B.S. | Female | 8 | CCU |

| 16 | Nurse | Nursing B.S. | Female | 5 | CCU |

| 17 | Nurse | Nursing B.S. | Female | <1 | CCU |

| 18 | Clinical supervisor | Management M.S. | Female | 27 | Nursing office |

| 19 | Clinical supervisor | Nursing B.S. | Female | 30 | Nursing office |

| 20 | Infection control supervisor | Nursing B.S. | Male | 13 | Nursing office |

| 21 | Service worker | Diploma | Female | 24 | CCU |

| 22 | Service worker | Diploma | Female | 11 | CCU |

| 23 | Service worker | Diploma | Male | 23 | CCU |

| 4 | Security | B.S. | Male | 20 | Hospital security unit |

| 25 | Security | B.S. | Male | 15 | Hospital security unit |

| 26 | Security | Diploma | Male | 18 | Hospital security unit |

Demographic Information

Due to the quality of its methodology, the present research’s sample size was determined during the research process after data saturation (n = 40). The inclusion criteria for patients and visitors were being alert and aware of the time, place, and person, having no known mental illnesses, being able to communicate verbally and non-verbally, understanding the Persian language, having no vision or hearing problems to communicate, having recent hospitalization experiences in the cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) for the patient, and having stable physical conditions during the interview. The visitors were selected from among the individuals whom the patient wished to visit. The inclusion criterion for the treatment team and managers was to have at least 6 months of clinical and managerial experience in the CICU. The exclusion criterion was an unwillingness to continue cooperation in the research.

The interviews were conducted in the CCU training room, the hospital management room, and the nursing service management room in a quiet environment. Moreover, the interviews were implemented in focus groups consisting of 3 to 7 people in 10 sessions to explain the present situation and problems facing the current visiting policy and provide solutions. A new visiting policy was planned and finalized in 2 sessions. The duration of the interviews ranged from 40 to 120 minutes. Interviews began with greetings and appreciation of participants for their presence with open-ended questions, such as ‘How do you see the visiting status?’ and ‘What is your experience of visiting?’ According to the answers, probing questions, such as ‘What do you mean by that?’ and ‘Explain more ...,’ were used to complete the information.

All interviews were recorded, listened to several times, and then written verbatim. The interview text was read several times to obtain an overall understanding.

In the next step, parts of the text were extracted as units of analysis (meaning units). These units were then changed into more concise meaning units. Concise meaning units were then abstracted and given coded labels. The entire text was considered when summarizing and tagging. Different codes were compared based on their differences and similarities and then placed into categories and subcategories to represent the manuscript text. The findings were repeatedly compared with the manuscript text and continuously edited.

3.3. Data Analysis

Content analysis was performed based on the method proposed by Graneheim and Lundman (12). This study presents its operational planning after identifying the existing problems. The current study began by evaluating the existing visiting policy. Besides, studies on visiting were reviewed simultaneously. Various qualitative methods, focus group discussion, observation, field notes, and the formation of planning groups were used to collect data. At all stages of the study, participants were involved in the data analysis process. A constant comparison analysis was used for data collection and analysis to reach agreement. The current status of the visiting policy was determined after analyzing the data and extracting the categories and themes.

3.4. Rigor

Lincoln and Guba criteria (13) were used to evaluate the data’s trustworthiness. In order to increase credibility, the researcher, as a member of the involved groups, used long interactions with the participants. The opinions of the supervisor and the consultant were used to organize focus group meetings, conduct interviews, and extract codes, subcategories, categories, and themes. The coded interviews were returned to the interviewees to see if the researcher had expressed their views. Also, the interview texts, along with the relevant codes and emerging categories, were sent to two observers who had Ph.D. in nursing and were faculty members involved in qualitative research to review the analysis process and comment on its accuracy.

The opinions of all stakeholders, including managers and planners, physicians, nurses, service staff, security guards, supervisors, patients, and visitors, were used in the visiting policy obtained in this study.

Then, according to the current problems and status, the proposed changes in the visiting policy were discussed by the planning group, consisting of a representative from each focus group. Finally, the visiting policy, which was the result of the participants’ discussion, was developed.

4. Results

The present research was performed on male and female participants, and the possible age range of the patients and their companions was 17 to 66 years, and their education level included middle school to Bachelor of Science (B.S.). Moreover, the education level of the hospital staff with specialties, including internal cardiology fellowship and cardiology, was Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), Master of Art (M.A.), B.S., and diploma, and their work experience varied between 8 months and 30 years.

The findings of the present research consist of two parts:

4.1. Part One

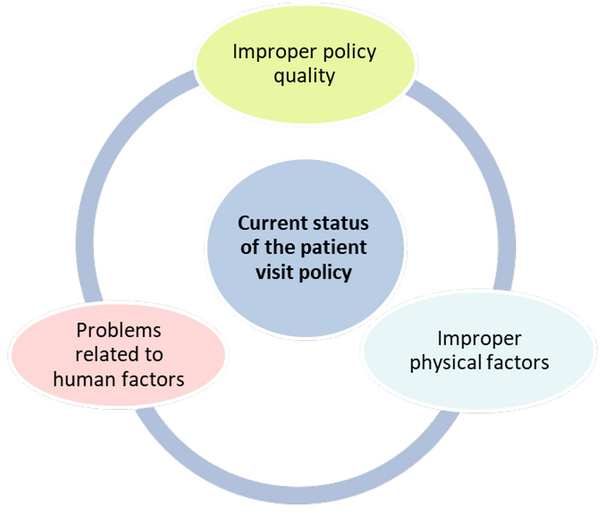

The current status of the visiting policy was explained, and the existing problems and barriers were identified through data collection and data analysis methods. The results from analyzing data and themes were obtained in the present study, and the existing problems and barriers included inappropriate physical factors, problems of human factors, and unsatisfactory quality of the visiting policy (Table 2) (Figure 1).

| Subcategories | Categories | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Defects in the design of the department building, | Inappropriate architecture | Inappropriate physical factors |

| Defects in the design of the hospital building | ||

| Defects in department equipment and its arrangement, Lack of necessities and comfort equipment, Incompetence of the department guide | Inadequacy of equipment |

An Example of the Formation of Categories and Themes

4.1.1. Inappropriate Physical Factors

The participants’ descriptions indicate defects in the design of the CCU building and equipment defects and their arrangement.

4.1.2. The Problems of Human Factors

This category consists of barriers and limitations of patients, weaknesses in the culture of visiting companions, weaknesses in controllers, and barriers and limitations of nurses, doctors, and managers.

4.1.3. Unsatisfactory Quality of the Visiting Policy

This topic includes the experience of unpleasant mental states, lack of a comprehensive plan, and weakness in information.

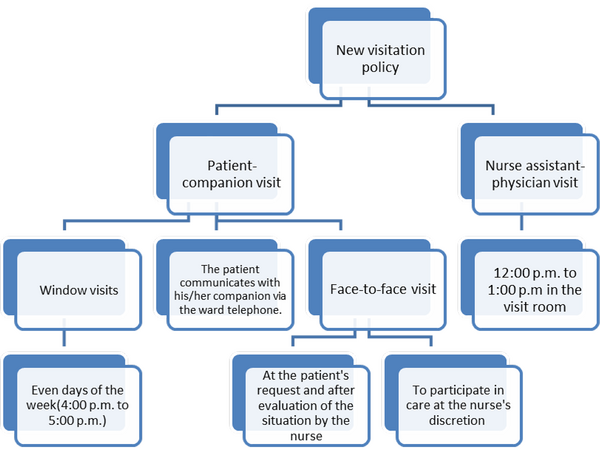

4.2. Part Two

In this part, after analyzing the data obtained from the existing problems of the visiting policy and obtaining the participants’ solutions, a planning group consisting of a representative from each focus group was formed, and the researcher announced a summary of the above opinions in two sessions. After the exchange of views among the group members, the applicable solutions were announced, and all group members agreed to the announced solutions. The solutions were organized and categorized, and an action plan was formulated (Table 3). Finally, the new visiting policy in the CCU of Ganjavian Hospital in Dezful was drawn based on these solutions (Figure 2).

| Variables | Objectives |

|---|---|

| The first challenge: Physical factors | |

| Goal 1: Organizing physical factors | (1) Organizing equipment and supplies, (2) organizing the physical structure |

| The second challenge: Human factors | |

| Goal 1: Determining the scope of human resource duties regarding the visiting policy | (1) Determining the scope of human resource duties regarding the visiting policy, (2) explaining the manager’s duties, (3) explaining the physicians’ duties , (4) explaining the nurses’ duties |

| Goal 2: Determining the scope of human resource duties in the visiting policy | (1) Explaining the security guards’ duties, (2) explaining the service staff’s duties, (3) explaining the families’ duties |

| The third challenge is the quality of the visiting policy | |

| Goal 1: Improving the quality of the visiting policy from a holistic perspective | (1) Organizing window visiting, (2) establishing patient-companion communication via telephone, (3) establishing organized face-to-face visiting, (4) determining the companion’s participation in the care process |

| Goal 2: Creating effective training | (1) Effective training, Objective, (2) effective training time, (3) providing effective training content (patient and companion training module) |

Designing a Visiting Policy in the Coronary Care Unit of Ganjovian Hospital

The visiting policy includes window and face-to-face visiting, and the patient would call his or her family or companion using the phone number of the ward dedicated to this purpose. The window visiting began from 04:00 p.m. to 05:00 p.m. on even days of the week. It was also decided that face-to-face visiting should take place under two conditions: (1) At the request of the patient and then by examining the conditions of the ward and the patient by the nurse and (2) to participate in care at the nurse’s discretion.

Regarding the physician-family visiting, it was also determined that only the patient’s assistant nurse should visit the physician at a specific time (12:00 p.m. to 1:00 p.m.) in the visiting room.

5. Discussion

The present study showed that the existing conditions have caused unpleasant mental states for both hospital staff and patients and companions. The reopening of critical care units to visitors is recommended by professional associations and specified by guidance documents worldwide (14). Today, the designers of the hospital building and the managers who are in charge of the building are making much effort to create a suitable environment for the patients (15). The current research shows the necessity of involving the hospital staff, particularly the nurses, according to their knowledge and experience, in order to create a suitable environment along with architectural experts; they also propose to improve the physical environment to promote the quality of visiting.

In this regard, studies show that severe restrictions on visiting the patient cause problems, such as mental health consequences for the patient, loneliness, depression symptoms, restlessness, aggression, reduced cognitive ability, and general dissatisfaction (16).

Although nurses generally have a negative attitude toward the open visiting policy and its consequences for the patient and family and nursing care (17), open visiting hours strengthen trust in families and lead to better working relationships between hospital staff and family members. Despite the nurses’ understanding of the importance of open visiting, the implementation of this strategy still faces many obstacles, such as the lack of human resources (18).

Holistic care is a comprehensive method of care that pays attention to all physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, social, and economic dimensions of the patient (17). Regarding the needs of patients, Xie et al. believe that providing holistic care could reduce patient stress because the patient’s care needs are met respectfully by combining the patient’s mental and physical needs with cultural and social beliefs, maintaining a healthy relationship, increasing trust, and therapeutic communication, which is a big step toward reducing patient anxiety, which is taken by the holistic care approach (18).

Not only should the nurse but also every member of the healthcare team should support the family members of the patient in the ICU in coping with the stressful situation (19). Creating more visiting opportunities and giving more information to family members about the process of treating patients will both improve psychosocial needs and reduce the psychological reactions induced in patients’ family members in ICUs (20). They also believe that if holistic and high-quality nursing care is to be provided, ICU nurses should not only pay attention to the patients but also to the psychological and social needs of their families (19).

The most important request of patients and their families or companions was to make face-to-face visiting. In addition to patients and companions, hospital staff also referred to scheduled and pre-planned face-to-face visiting (21). Attempts are made to improve the quality of visiting in the new visiting policy by giving more opportunities for patient-companion and companion-physician visiting, focusing on ensuring complete and timely information, allocating a room for companion-physician and patient-companion visiting, and paying attention to the required equipment.

5.1. Conclusions

The time has come to fulfill the rights of individuals by strengthening constructive beliefs and changing destructive beliefs with a holistic perspective. The results of the present study showed that the CCU visiting policy has the potential to change. The results also showed that in order to change the visiting policy, the needs of all stakeholders must be considered. In the new visiting policy, efforts are being made to improve the quality of visiting by providing more opportunities for patient-companion and doctor-companion visiting, focusing on ensuring complete and timely information, assigning rooms for doctor-companion and patient-companion visiting, and paying attention to the required equipment.

5.2. Limitations

However, this research has some limitations, such as the fact that it cannot be fully generalized to other centers due to the local and single-centered nature of the research. However, it can be regarded as a model for policymakers and planners, while the cases adjust it according to their conditions.