1. Background

Nearly 85% of older adults suffer from at least one chronic disease (1). Aging is associated with a high prevalence of chronic diseases such as cancer due to prolonged exposure to multiple risk factors (2-4). In older adults, cancer is the second and third leading cause of death in the United States and Iran, respectively (5). Cancer may restrict the function of the older adult, making these patients dependent on family caregivers to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) (6, 7).

A family caregiver is a family member (e.g., spouse, child, relative, or friend) who provides care and assistance to a person without charging any fee (6). About 90% of married older people with chronic diseases and 80% of single older adults are cared for by their spouses and children, respectively (8). Family caregivers bear a heavy burden of care due to lack of sufficient information, lack of necessary skills and preparation, lack of necessary resources to meet the needs of the older adult, and interference of their care responsibilities with their everyday tasks (9-12). The burden of care affects different subscales of a caregiver’s health-promoting lifestyle (6, 13-15).

A health-promoting lifestyle refers to behaviors that directly promote a person’s well-being, self-efficacy, and self-realization. Various subscales of a health-promoting lifestyle include spiritual growth (having motivation, purpose, satisfaction, and a sense of usefulness), interpersonal relations (maintaining intimate relationships), stress management (identifying and managing sources of stress), health responsibility (trying to stay healthy), physical activity (pursuing a regular exercise program), and nutrition (following a regular, healthy eating pattern) (16).

A healthy lifestyle can help caregivers substantially promote their well-being, dramatically improve the quality of their lives, easily manage stressful life events, and considerably reduce the incidence of health conditions (17, 18). Studies suggest that the quality and effectiveness of care for older adults with cancer can be improved if the necessary external support and professional guidance are provided to their caregivers (6, 15, 19). Social support is among the various types of support that caregivers may receive.

Social support is the exchange of resources between at least two people (a provider and a recipient) to improve the recipient's health. In this case, the support recipient believes that he/she is valued, respected, interested, and cared for by others (20). The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified four domains for social support, including emotional, instrumental (tangible), informational, and appraisal support.

Emotional support means having access to a trusted person who welcomes, listens, empathizes, respects, reassures, and comforts one in stressful situations. Instrumental (Tangible) support means helping people with ADLs and taking them to support centers if needed. Informational Support refers to the provision of adequate information and guidance by experts. Finally, appraisal support refers to the evaluation of individual skills, abilities, and values (21).

Social support can be provided either in person (e.g., in the form of counseling, peer, and friend support groups) or remotely (e.g., by phone or online) (22-26). Social support can play a critical role in maintaining the health of the general public and reducing the negative effects of social pressures (21, 27), thereby developing individual competencies, promoting coping strategies, creating a sense of worthiness, and reducing anxiety and depression in caregivers (28, 29).

In addition, support groups can effectively improve the quality of life and reduce the stress and care burden of family caregivers of chronically ill (e.g., dementia and cancer) patients (30, 31). Furthermore, a lack of social support has been shown to predict depression and other mental health problems in caregivers (20, 28, 32).

Studies indicate that providing care for ill and disabled older adults affects different aspects of family caregivers' health. In addition, the cost of care or frequent hospitalization of older adults forces their caregivers to quit their jobs or apply for part-time jobs. These challenges influence the quality of life and health-promoting behaviors of caregivers.

Providing a social support program for family caregivers seems to encourage them to engage in health-promoting behaviors, thereby improving various subscales of their health. The multifaceted needs of caregivers are often overlooked, and there is a lack of attention to the role of social support. Caregivers may not receive sufficient guidance and support, leading to confusion in accepting their role.

Addressing Social Support for family caregivers of older adults with cancer lies in a comprehensive approach to meeting their diverse needs. While most studies focus on the patient's well-being, caregivers are often neglected despite their crucial role. Emphasizing the importance of addressing the health of caregivers as "hidden patients," this research highlights the need to design and implement comprehensive Social Support Programs in various informational, evaluation, instrumental, and emotional dimensions to improve the burden of family caregivers.

2. Objectives

Due to the limited research in this field, this study aimed to investigate the effect of a social support Program on the health-promoting lifestyle of caregivers of older adults with cancer.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This was a quasi-experimental study.

3.2. Setting and Sample

The study population of this study consisted of all family caregivers of older adults with cancer visiting the Outpatient Department of Imam Hassan Mojtaba Radiotherapy and Oncology Center in Dezful, Iran, in 2021. The inclusion criteria were an average of 31 hours of caregiving per week for at least three months, easy access to smartphones and the Internet, no mental disorders, ability to read and write, physical capability to participate in in-person sessions, participation in no similar support program during or before the intervention, and willingness to participate in the study. In addition, the eligible participants provided care to older adults over 65 years of age who had been diagnosed with cancer by a physician at least 3 months before the intervention. Individuals who died during the intervention and those who missed more than two consecutive sessions were excluded.

The sample size was calculated in G*Power as 58 by considering an effect size of 0.4, a power of 80%, a type I error of 5%, a total number of variables of 5, a degree of freedom of 1, and a loss to follow-up of 10%. Using consecutive sampling, eligible people were enrolled and assigned to the intervention and control groups (29 individuals per group).

3.3. Data Collection

The data were collected using a researcher-made sociodemographic questionnaire and the health-promoting lifestyle profile II (HPLP-II). The sociodemographic questionnaire included questions about the caregivers’ age, gender, marital status, job, number of children, and health status.

The HPLP-II was developed by Walker and Hill-Polerecky in 1997 (33). This 52-item tool has six subscales, including spiritual growth (9 items), interpersonal relations (9 items), stress management (8 items), health responsibility (9 items), Physical activity (8 items), and nutrition (9 items). The items are scored on a Four-Point Likert Scale: Never, sometimes, often, and always. The minimum and maximum HPLP-II scores are 52 and 208, respectively. A higher HPLP-II score indicates a healthier lifestyle.

Exploratory factor analysis was used to confirm the construct validity of the original version of HPLP-II. In addition, factor loadings were confirmed with a variance of 47.1 using varimax rotation (34). The internal consistency method confirmed the reliability of the whole scale and its subscales. The obtained Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.79 to 0.94. In addition, the three-week test-retest reliability of HPLP-II was 0.89 (33).

Mohammadi Zeidi et al. assessed the psychometric properties of the Persian version of HPLP-II. They used exploratory factor analysis to confirm the validity of this tool and confirmed its factor loadings with a variance of 67.5 using varimax rotation. In addition, they confirmed the reliability of the whole scale by assessing its internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha value = 0.82) (35).

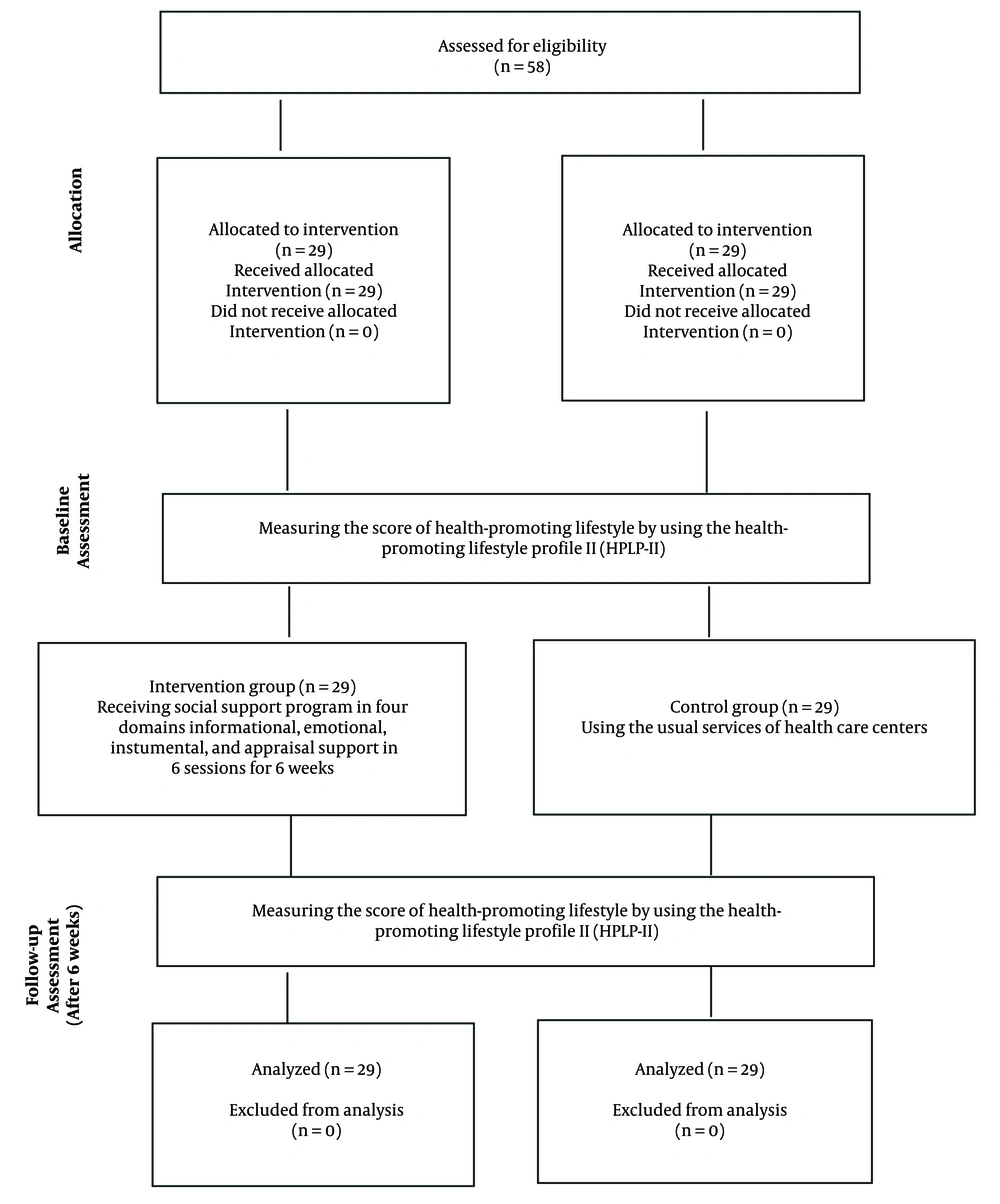

The sample was selected using consecutive sampling after obtaining written informed consent from eligible people. A total of 58 individuals were selected as the sample based on the inclusion criteria. Then, the selected people were assigned to two intervention and control groups. All participants received sealed, opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes to conceal the allocation sequence. After allocation, participants completed the research questionnaires before the intervention (the pretest stage). Then, the intervention group members attended several sessions of the social support program in four domains: Informational, emotional, instrumental, and appraisal support (Figure 1).

The participants received information and education on the health-promoting lifestyle in the informational support domain. The educational content was prepared using up-to-date English and Persian sources. Two professors from the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, who had experience with interventions in this stage, were continuously present and supervised the compilation and presentation of the educational content. Before the intervention, four geriatric nursing professors verified the validity of the tool.

The participants attended six 60 - 90-minute sessions in Ganjavian Hospital to promote the subscales of spiritual growth, interpersonal relations, stress management, health responsibility, physical activity, and nutrition.

In the emotional support domain, the researcher aimed to establish a platform for caregivers to share their experiences following each face-to-face meeting, thereby fostering empathy, love, trust, and caring. Additionally, the researcher maintained regular in-person or remote contact (e.g., by phone or via WhatsApp Messenger) with family caregivers once a week, providing emotional support through active listening, encouragement, and reminders of their strengths and coping abilities.

In the instrumental support domain, before the intervention, the participants' caregiving needs were identified, including changing the patient's colostomy bag correctly, checking the patient's vital signs properly, and finding the location of cancer care centers. Accordingly, the researcher provided the necessary practical training to caregivers of older adults on how to change a patient's colostomy bag and how to check vital signs. The researcher also gave the caregivers the addresses of active cancer care and treatment centers in Dezful.

In the appraisal support domain, the researcher asked questions to evaluate caregivers’ theoretical and practical skills in the emotional and instrumental domains. Finally, HPLP-II was used in the posttest stage to assess the informational support domain.

The control group members only received routine hospital training. Participants in both groups completed the questionnaires six weeks after the intervention (the posttest stage).

3.4. Ethical Considerations

The participants were first informed of the research objectives, the confidentiality of their information, and the voluntary nature of their participation in the research. Each participant then signed a written informed consent form. To comply with the principles of research ethics, caregivers in both groups were given an educational package on health-promoting lifestyles at the end of the study.

3.5. Statistical Analyses

The data were analyzed in SPSS 16 using descriptive statistics (percentage and frequency) and inferential statistics (independent t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, and chi-square test) (P < 0.05).

4. Results

All participants (n = 58) completed the study instruments, and all were included in the final analysis. The demographic characteristics of the participants indicated that a majority were female (approximately 62%) and married (around 90%) (Table 1). The average age of the older adults receiving family care in the intervention group was 70.76 years, while in the control group, it was 71.31 years. Notably, 25 older adults in the intervention group and 22 in the control group had a history of cancer lasting more than two years (Table 1).

| Variables | Intervention Number | Control Number | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Older adults under care | - | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 13 (44.8) | 16 (55.2) | |

| Female | 16 (55.2) | 13 (44.8) | |

| Married Status | - | ||

| Single | 9 (47.4) | 10 (52.6) | |

| Married | 20 (51.3) | 19 (48.7) | |

| Job | - | ||

| Employee | 20 (43.8) | 19 (63.3) | |

| Unemployed | 22 (52.4) | 20 (47.6) | |

| Duration of cancer | |||

| Under 1 year | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | |

| Under 1 year | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | |

| More than 2 years | 25 (53.2) | 22 (46.8) | |

| Treatment type | - | ||

| Chemotherapy or radiation therapy | 2 (14.3) | 12 (87.5) | |

| Chemotherapy and radiation therapy | 27 (61.4) | 17 (38.6) | |

| Age | 70.76 ± 5.10 | 71.31 ± 6.12 | - |

| Family caregivers of older adults with cancer | |||

| Gender | 0.58 b | ||

| Male | 10 (34.5) | 12 (41.4) | |

| Female | 19 (65.5) | 17 (58.6) | |

| Married Status | 0.38 b | ||

| Single | 2 (6.8) | 4 (13.7) | |

| Married | 27 (93.2) | 25 (86.3) | |

| Number of children | 0.76 b | ||

| 0 | 1 (1.7) | 3 (5.1) | |

| 1 | 3 (5.1) | 3 (5.1) | |

| 2 | 11 (18.9) | 11 (18.9) | |

| 2 < | 14 (24.1) | 12 (20.6) | |

| Job | 0.93 b | ||

| Employee | 6 (20.6) | 7 (24) | |

| Housekeeper | 13 (45) | 13 (45) | |

| Self-employed | 10 (34.4) | 9 (31) | |

| Medical history | 0.40 b | ||

| No | 18 (62) | 21 (72.5) | |

| Yes | 11 (38) | 8 (27.5) | |

| Drug history | 0.54 b | ||

| Yes | 19 (38) | 22 (44) | |

| No | 31 (62) | 28 (56) | |

| Age | 44.07 ± 11.58 | 42.00 ± 7.2 | 0.42 c |

Comparison of Demographic Variables of the Older Adults Under Care and Family Caregivers of Older Adults with Cancer in Intervention (n = 28) and Control (n = 28) Groups a

Prior to the intervention, there was no significant difference in the HPLP-II scores between the intervention group (113.10 ± 16.64) and the control group (116.58 ± 24.95) (P > 0.05). However, following the intervention, a significant difference emerged in HPLP-II scores, with the intervention group scoring higher (129.58 ± 15.21) compared to the control group (116.13 ± 24.62) (P = 0.01).

Further analysis of specific subscales revealed significant differences post-intervention. In the interpersonal relations subscale, participants in the intervention group had a mean score of 24.58 ± 3.00, while those in the control group scored 21.62 ± 5.41 (P = 0.01). Similarly, in the health responsibility subscale, the intervention group scored significantly higher at 26.68 ± 2.79 compared to the control group's score of 22.00 ± 5.37 (P = 0.01). Conversely, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in other subscales (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

| Variables and Subscales | Before Intervention | P-Value b | 6 Weeks After Intervention | P-Value b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | |||

| Spiritual growth | 21.31 ± 5.77 | 21.00 ± 4.01 | 0.81 | 21.48 ± 5.55 | 23.65 ± 3.97 | 0.09 |

| Interpersonal relations | 22.31 ± 5.77 | 21.55 ± 4.00 | 0.56 | 21.62 ± 5.41 | 24.58 ± 3.00 | 0.01 |

| Stress management | 16.37 ± 3.98 | 15.51 ± 2.888 | 0.35 | 16.03 ± 4.48 | 17.44 ± 2.92 | 0.16 |

| Health responsibility | 22.24 ± 5.76 | 20.79 ± 3.22 | 0.24 | 22.00 ± 5.37 | 26.68 ± 2.79 | 0.00 |

| Physical activity | 12.20 ± 4.30 | 13.96 ± 4.69 | 0.13 | 12.48 ± 4.46 | 14.55 ± 4.25 | 0.07 |

| Nutrition | 22.13 ± 4.22 | 20.27 ± 2.99 | 0. 58 | 22.51 ± 3.91 | 14.55 ± 4.25 | 0.86 |

| Health-promoting lifestyle | 116.58 ± 24.95 | 113.10 ± 16.64 | 0.53 | 116.13 ± 24.62 | 129.58 ± 15.21 | 0.01 |

Comparison of the Mean of Health-Promoting Lifestyle and Its Subscales in Two Groups (n = 58) a

5. Discussion

The present study investigated the impact of a social support Program on the health-promoting lifestyle of caregivers of older adults with cancer. The proposed social support Program was found to effectively improve the health-promoting lifestyle of caregivers.

Pongthavornkamol et al. investigated the effects of support groups on health-promoting behaviors and the quality of life of female breast cancer patients. Consistent with the findings of the present study, Pongthavornkamol et al. concluded that training programs provided to increase women’s knowledge of breast cancer, symptom and complication management, and stress management can significantly improve the health-promoting behaviors of cancer patients (36). Attending support group sessions allows caregivers to express their feelings, share their experiences, and learn healthy coping strategies and skills. It also remarkably increases the quality of their lives and reduces the levels of depression and anxiety they experience over time (31).

The mean interpersonal relations score of the caregivers of older adults with cancer in the intervention group significantly increased after the intervention. Similarly, Khiyali et al. investigated the effect of an educational intervention based on Pender's Health Promotion Model on the lifestyle of patients with type 2 diabetes and observed a significant improvement in the interpersonal relations of the intervention group members after the intervention (37). This improvement in interpersonal relations is probably because, in face-to-face sessions, caregivers have the opportunity to exchange ideas and discuss the problems they usually face when caring for an older adult with cancer.

Social support improves the physical health of caregivers; hence, health sessions organized as part of a Social Support Program can increase people’s awareness and sense of responsibility, encouraging them to improve their lifestyle (10, 28, 38). The proposed Social Support Program had a significant positive effect on the health responsibility of caregivers of older adults with cancer. In line with this finding, Najafi et al. concluded that peer support significantly increases the health responsibility and health-promoting lifestyle of women with breast cancer (39).

Spiritual growth is a key component of a health-promoting lifestyle that is related to all subscales of quality of life (40). The social support program proposed in this study slightly improved the spiritual growth of family caregivers of older adults with cancer in the intervention group compared to the pretest. However, these changes were not significant compared to the control group.

In line with this result, Babaei et al. found that an educational intervention based on a health-promoting lifestyle did not significantly improve the spiritual development of individuals susceptible to cardiovascular disease (41). The lack of significant impact of the social support program on the spiritual growth of family caregivers of older adults with cancer could be due to the program's duration, intensity, and tailoring to individual needs. The program might not have been long or intense enough to produce notable changes in spiritual growth.

Additionally, it may not have been customized to the specific needs and preferences of the caregivers, limiting its effectiveness. Furthermore, inadequate assessments and monitoring of caregivers' needs and outcomes could hinder the program's ability to address their spiritual needs effectively. Similar studies suggest that long-term combined intervention approaches can greatly enhance the effect of social support programs on spiritual growth (42).

The social support program proposed in this study significantly improved the stress management of family caregivers of older adults with cancer in the intervention group compared to the pretest. However, these changes were not significant compared to the control group.

In line with this finding, Kozachik et al. observed that a 16-week nurse-led supportive intervention did not effectively reduce symptoms of stress and depression in caregivers of cancer patients (43). Conversely, Ghezelseflo et al. found that resilience training significantly reduced stress and communication problems in primary caregivers of older adults with Alzheimer's disease (44).

Research shows that the effectiveness of social support interventions is influenced by the quality and type of support, caregivers' specific needs, and the complexity of the caregiving situation. Caregivers of older adults with cancer encounter challenges related to the unique psychosocial needs of this group, the impact of caregiving on their well-being, and the evolving caregiving role as the patient's condition changes. Additionally, factors such as coping mechanisms, levels of social support, and other stressors can impact the outcomes of support programs.

The proposed social support program did not significantly increase the level of physical activity in the intervention group, and these changes were not significant compared to the control group. A social support program for the physical activity level of family caregivers of older adults with cancer may be ineffective due to the complexity of the caregiving situation, the varying needs of caregivers and care recipients, and the quality of support provided (45, 46).

In contrast, Cuthbert et al. concluded that an exercise-based intervention can be used separately or in conjunction with other interventions to improve the quality of life, health, and well-being of caregivers of cancer patients (47).

Effective strategies for promoting physical activity in family caregivers of older adults with cancer involve a multidimensional approach addressing barriers and facilitators. Interventions can integrate self-efficacy promotion, realistic goal support, motivation enhancement, and social support optimization. Considering social-ecological determinants, such as intrapersonal, interpersonal, and environmental factors, is crucial.

Incorporating activity into routines, using coping strategies, setting motivational goals, and experiencing walking benefits can facilitate adherence. Instruction in behavioral and cognitive strategies, including individualized advice from healthcare providers, can foster engagement in physical activity.

Caregivers of older adults with chronic diseases often have poor nutritional status, which deteriorates their performance, health, well-being, and quality of life (48, 49). This study found an insignificant impact of the proposed Social Support Program on caregivers' nutrition, possibly due to complex needs and the evolving caregiving role (50).

To improve effectiveness, interventions can be tailored to unique circumstances, provide ongoing support and adaptation, and consider the complex factors influencing caregiver well-being. This research demonstrates the significant potential of social support interventions to enhance the health and well-being of cancer caregivers.

By promoting positive lifestyle changes, these interventions can help caregivers better cope with caregiving demands and maintain their health. The findings highlight the need for healthcare providers to proactively support caregivers as integral members of the care team.

5.1. Limitations

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, strict health protocols were implemented during face-to-face sessions to ensure the safety of participants. These measures included temperature checks at the beginning of each session using a thermometer, mandatory face mask-wearing, and adherence to social distancing guidelines. While necessary to protect the health and well-being of all involved, these precautions may have influenced the overall experience and dynamics of the face-to-face interactions within the study.

5.2. Conclusions

The proposed Social Support Program significantly improved the health-promoting lifestyle of family caregivers of older adults with cancer. Despite the numerous physical, mental, spiritual, economic, and social impacts of caregiving on family caregivers of older adults, the proposed Social Support Program can enable these individuals to adopt a health-promoting lifestyle, thereby increasing their life expectancy and improving their quality of life.

The six-week social support program improved all health-promoting lifestyle subscales among intervention group members, although differences were not statistically significant in some cases. The provision of social support programs by external sources and healthcare team members (e.g., nurses) can positively impact various aspects of caregivers’ health and encourage them to engage in health-promoting behaviors.

Therefore, relevant health centers are recommended to develop a comprehensive guide for caregivers of older adults with cancer based on the proposed social support program. Managers and policymakers can invest in comprehensive support programs prioritizing caregiver well-being, increasing awareness and training, enhancing resource access, promoting self-care, and addressing financial and practical needs. These actions can better equip caregivers to cope with caregiving challenges, ultimately improving overall well-being and care quality for both patients and caregivers.

Future research directions include exploring the long-term effects of such programs, identifying effective program components to design more targeted interventions, assessing their impact on the quality of patient care, and conducting larger and more diverse studies for broader application and subgroup analyses. In addition, researchers are encouraged to conduct similar studies on larger populations consisting of caregivers of older adults with other chronic diseases and different cultural backgrounds.